An Introduction to the Theory and Practice of Light Microscopy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subwavelength Resolution Fourier Ptychography with Hemispherical Digital Condensers

Subwavelength resolution Fourier ptychography with hemispherical digital condensers AN PAN,1,2 YAN ZHANG,1,2 KAI WEN,1,3 MAOSEN LI,4 MEILING ZHOU,1,2 JUNWEI MIN,1 MING LEI,1 AND BAOLI YAO1,* 1State Key Laboratory of Transient Optics and Photonics, Xi’an Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi’an 710119, China 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3College of Physics and Information Technology, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an 710071, China 4Xidian University, Xi’an 710071, China *[email protected] Abstract: Fourier ptychography (FP) is a promising computational imaging technique that overcomes the physical space-bandwidth product (SBP) limit of a conventional microscope by applying angular diversity illuminations. However, to date, the effective imaging numerical aperture (NA) achievable with a commercial LED board is still limited to the range of 0.3−0.7 with a 4×/0.1NA objective due to the constraint of planar geometry with weak illumination brightness and attenuated signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Thus the highest achievable half-pitch resolution is usually constrained between 500−1000 nm, which cannot fulfill some needs of high-resolution biomedical imaging applications. Although it is possible to improve the resolution by using a higher magnification objective with larger NA instead of enlarging the illumination NA, the SBP is suppressed to some extent, making the FP technique less appealing, since the reduction of field-of-view (FOV) is much larger than the improvement of resolution in this FP platform. Herein, in this paper, we initially present a subwavelength resolution Fourier ptychography (SRFP) platform with a hemispherical digital condenser to provide high-angle programmable plane-wave illuminations of 0.95NA, attaining a 4×/0.1NA objective with the final effective imaging performance of 1.05NA at a half-pitch resolution of 244 nm with a wavelength of 465 nm across a wide FOV of 14.60 mm2, corresponding to an SBP of 245 megapixels. -

Introduction to Light Microscopy

Introduction to light microscopy A CAMDU training course Claire Mitchell, Imaging specialist, L1.01, 08-10-2018 Contents 1.Introduction to light microscopy 2.Different types of microscope 3.Fluorescence techniques 4.Acquiring quantitative microscopy data 1. Introduction to light microscopy 1.1 Light and its properties 1.2 A simple microscope 1.3 The resolution limit 1.1 Light and its properties 1.1.1 What is light? An electromagnetic wave A massless particle AND γ commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EM-Wave.gif www.particlezoo.net 1.1.2 Properties of waves Light waves are transverse waves – they oscillate orthogonally to the direction of propagation Important properties of light: wavelength, frequency, speed, amplitude, phase, polarisation upload.wikimedia.org 1.1.3 The electromagnetic spectrum 퐸푝ℎ표푡표푛 = ℎν 푐 = λν 퐸푝ℎ표푡표푛 = photon energy ℎ = Planck’s constant ν = frequency 푐 = speed of light λ = wavelength pion.cz/en/article/electromagnetic-spectrum 1.1.4 Refraction Light bends when it encounters a change in refractive index e.g. air to glass www.thetastesf.com files.askiitians.com hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/Sound/imgsou/refr.gif 1.1.5 Diffraction Light waves spread out when they encounter an aperture. electron6.phys.utk.edu/light/1/Diffraction.htm The smaller the aperture, the larger the spread of light. 1.1.6 Interference When waves overlap, they add together in a process called interference. peak + peak = 2 x peak constructive trough + trough = 2 x trough peak + trough = 0 destructive www.acs.psu.edu/drussell/demos/superposition/superposition.html 1.2 A simple microscope 1.2.1 Using lenses for refraction 1 1 1 푣 = + 푚 = physicsclassroom.com 푓 푢 푣 푢 cdn.education.com/files/ Light bends as it encounters each air/glass interface of a lens. -

The-Pathologists-Microscope.Pdf

The Pathologist’s Microscope The Pathologist’s Microscope Rudolf Virchow, the father of Pathology, had available to him wonderful microscopes during the 1850’s to 1880’s, but the one you have now is far better. Your microscope is the most highly perfected of all scientific instruments. These brief notes on alignment, the objective lens, the condenser, and the eyepieces are what you need to know to get the most out of your microscope and to feel comfortable using it. Figure 1 illustrates the important parts of a generic modern light microscope. Figure 1 - Parts of the Microscope UNC Pathology & Lab Med, MSL, July 2013 1 The Pathologist’s Microscope Alignment August Köhler, in 1870, invented the method for aligning the microscope’s optical system that is still used in all modern microscopes. To get the most from your microscope it should be Köhler aligned. Here is how: 1. Focus a specimen slide at 10X. 2. Open the field iris and the condenser iris. 3. Observe the specimen and close the field iris until its shadow appears on the specimen. 4. Use the condenser focus knob to bring the field iris into focus on the specimen. Try for as sharp an image of the iris as you can get. If you can’t focus the field iris, check the condenser for a flip-in lens and find the configuration that lets you see the field iris. You may also have to move the field iris into the field of view (step 5) if it is grossly misaligned. 5.Center the field iris with the condenser centering screws. -

To Take Into Consideration the Propriety Of

his was the subject for discussion amongst the seventeen microscopists who met at Edwin Quekett’s house No 50 Wellclose Square, in the Borough of Stepney, East London on 3rd September 1839. It was resolved that such a society be formed Tand a provisional committee be appointed to carry this resolution into effect. The appointed provisional committee of seven were to be responsible for the formation of our society, they held meetings at their homes and drew up a set of rules. They adopted the name ‘Microscopical Society of London’ and arranged a public meeting on the 20th December 1839 at the rooms of the Horticultural Society, 21 Regent Street. Where a Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward © National Portrait Gallery, London President, Treasurer and Secretary were elected, the provisional committee also selected the size of almost airtight containers. Together with George 3 x 1 inch as a standard for glass slides. Loddiges, he saw the potential benefit of protection from sea air damage allowing the transport of plants Each of the members of the provisional committee between continents. This Ward published in 1834 had their own background which we have briefly and eventually his cases enabled the introduction described on the following pages, as you will see of the tea plant to Assam from China and rubber they are a diverse range of professionals. plants to Malaysia from South America. His glass plant cases allowed the growth of orchids and ferns in the Victorian home and in 1842 he wrote a book on the subject. However glass was subject to a tax making cases expensive so Ward lobbied successfully for its repeal in 1845. -

The Scientific Legacy of Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek

196 Chapter 12 Chapter 12 The Scientific Legacy of Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek This final chapter discusses some of the developments in science on which Antoni van Leeuwenhoek left his mark from his death to the beginning of the 21st century. It will review the influence of his work and listen for the echoes of his name almost three hundred years after his death. Figure 12.1 Nineteenth-century microscope by George Adams with eyepiece, objective, various attachments and a mirror to illuminate the specimen © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2016 | doi 10.1163/9789004304307_013 The Scientific Legacy of Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek 197 Microscopy Microscopes have become increasingly complex and more versatile, but much easier to use, since the time of Van Leeuwenhoek. Single-lens microscopes went out of use in the 18th century, when compound microscopes with at least two lenses ‒ an eyepiece and an objective ‒ became the norm. Many innovations came from England. Firstly, the illumination of speci- mens was improved. During Van Leeuwenhoek’s lifetime, John Marshall (1663–1725) had developed a simple illumination system using a mirror attached to the foot of the microscope. John Cuff (1708–1772) used an extra lens, a condenser, in 1744 to concentrate light on the specimen. In 1755, George Adams (1720–1773) developed a microscope with a rotating wheel holding objectives with different powers of magnification. Sliding holders in which a variety of specimens could be mounted at one time can be traced back to the rotating holders on the single-lensed microscopes used by Christiaan Huygens and J. De Pouilly (or Depovilly) in the 1670s, and were developed for use with compound microscopes. -

Simple and Open 4F Koehler Transmitted Illumination System for Low- Cost Microscopic Imaging and Teaching

Simple and open 4f Koehler transmitted illumination system for low- cost microscopic imaging and teaching Jorge Madrid-Wolff1, Manu Forero-Shelton2 1- Department of Biomedical Engineering, Universidad de los Andes, Bogota, Colombia 2- Department of Physics, Universidad de los Andes, Bogota, Colombia [email protected] ORCID: JMW: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3945-538X MFS: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7989-0311 Any potential competing interests: NO Funding information: 1) Department of Physics, Universidad de los Andes, Colombia, 2) Colciencias grant 712 “Convocatoria Para Proyectos De Investigación En Ciencias Básicas“ 3) Project termination grant from the Faculty of Sciences, Universidad de los Andes, Colombia. Author contributions: JMW Investigation, Visualization, Writing (Original Draft Preparation) MFS Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing(Original Draft Preparation) 1 Title Simple and open 4f Koehler transmitted illumination system for low-cost microscopic imaging and teaching Abstract Koehler transillumination is a powerful imaging method, yet commercial Koehler condensers are difficult to integrate into tabletop systems and make learning the concepts of Koehler illumination difficult. We propose a simple 4f Koehler illumination system that offers advantages with respect to building simplicity, cost and compatibility with tabletop systems, which can be integrated with open source Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopes (LSFMs). With those applications in mind as well as teaching, we provide -

160-Series-Manual.Pdf

National Optical & Scientific Instruments Inc. 6508 Tri-County Parkway Schertz, Texas 78154 Phone (210) 590-9010 Fax (210) 590-1104 INSTRUCTIONS FOR 160 SERIES COMPOUND BIOLOGICAL MICROSCOPES Copyright © 1/2/01 National Optical & Scientific Instrument Inc. Models 160 (monocular head), 161 (dual head), 162 (binocular head), 163 (trinocular head), all have the same stand and stand features…only the head portion differs…illustrated is Model 162. Knurled diopter ring Sliding interpupillary adjustment, grips located on both left and right Widefield 10x/18 side of diopter scale eyepiece Mark on side of eyepiece tube for indexing diopter reading Interpupillary scale Knurled head locking screw Viewing head of microscope Revolving nosepiece Arm of microscope stand Objective lenses Two knurled locking screws for Specimen holder securing specimen holder to stage (mechanical stage) Stage Abbe condenser locking screw Abbe condenser 1.25 N.A. Iris diaphragm lever Coarse focus knob Filter holder for 32mm filter Control knob for Fine focus knob Abbe condenser Recess for 45mm filter Illuminator condenser Knobs controlling X and Y movement of mechanical stage Light intensity Base control knob Detachable power supply cord Tension adjustment 100v-240v, 50H/60H input 12 volt DC knob Output ON/OFF switch DC Plug Socket 12 Volt DC Switching Power Supply 3 INTRODUCTION Thank you for your purchase of a National microscope. It is a well built, precision instrument carefully checked to assure that it reaches you in good condition. It is designed for ease of operation and years of carefree use. The information in this manual probably far exceeds what you will need to know in order to operate and maintain your microscope. -

How to Perform DIC Microscopy Introduction Principle

How To Perform DIC Microscopy Technical Support Note #T-3 Date Created: 12/5/03 Category:Techniques Date Modified: 00/00/00 Keywords: DIC, Differential Interference Contrast, Axiovert 200M Introduction Many biological specimens cannot be effectively visualized using ordinary bright-field microscopy because their images produce very little contrast, rendering them essentially invisible. Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) microscopy is an excellent method for generating contrast by converting specimen optical path gradients into amplitude differences that can be visualized by the human eye. Images produced using DIC optics have a distinct relief-like, shadow-cast appearance giving an illusion of three dimensionality. This tutorial will cover the optical components used in DIC microscopy, the basic principles governing how it works, and the proper alignment of DIC optical components for the Zeiss Axiovert 200M research microscope. Principle DIC microscopy utilizes a system of dual-beam interference optics that transforms local gradients in optical path length in a specimen into regions of contrast in an image. Optical path length is a product of the refractive index and thickness between two points on an optical path and is directly related to the transit time and number of cycles of vibration exhibited by a wave of light traveling between two points. The basic principle of DIC is illustrated in figure 4. Waves of plane polarized light are split into two beams by the condenser prism. These pairs of beams emerge from the condenser lens traveling in parallel to one another and pass through the specimen. The spacing between these paired beams of light varies depending on the prism used, but generally ranges between 0.2-2µm. -

Setting up Kohler Illumination on the Nikon TE2000U Inverted Microscope

Setting up Kohler Illumination on the Nikon TE2000U Inverted Microscope Koehler illumination1 is an illumination technique that provides optimum resolution and contrast when using a bright-field light microscope. It does this by aligning and focussing the illumination light path, and critically setting the iris apertures of the microscope to best match the objective lens. This sheet is only for aligning the condenser on the Nikon inverted microscope. 1) Place a slide on the stage and bring the specimen into focus. If the microscope condenser is way out of alignment, you will have to roughly adjust the condenser height to give adequate illumination to focus on the specimen. There are two white tape indicators on the left side of the condenser that will be nearly aligned when the condenser is at the correct height. 2) Stop down the Field Diaphragm Iris so that you can see it in the field of view. This is the vertical diaphragm [black] slider at the top right hand of the condenser [at the highest point of the microscope]. You slide the lever downwards to close [stop down] the iris, and up again to re-open the iris. 3) Focus the Condenser by adjusting its height. Turn the focus knob on the left or right side of the condenser until the shadow edge of the Field Diaphragm Iris is in sharp focus when viewed down the microscope eyepieces. This iris edge may be blurred if your specimen is very thick, so get it as sharp in focus as possible. 4) Open the Field Diaphragm Iris to near the edge of the field of view and centre it to the middle, using the condenser centering controls. -

This Is a Repository Copy of Ptychography. White Rose

This is a repository copy of Ptychography. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/127795/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Rodenburg, J.M. orcid.org/0000-0002-1059-8179 and Maiden, A.M. (2019) Ptychography. In: Hawkes, P.W. and Spence, J.C.H., (eds.) Springer Handbook of Microscopy. Springer Handbooks . Springer . ISBN 9783030000684 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00069-1_17 This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of a chapter published in Hawkes P.W., Spence J.C.H. (eds) Springer Handbook of Microscopy. The final authenticated version is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00069-1_17. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Ptychography John Rodenburg and Andy Maiden Abstract: Ptychography is a computational imaging technique. A detector records an extensive data set consisting of many inference patterns obtained as an object is displaced to various positions relative to an illumination field. -

Seminar Series About Optics and Microscopy

Fundamentals in optics and microscopy NIF Optical Seminar Jan 16th 2019 - Aurelien Breakdown Detections Illuminations Magic NIF Optical Seminar Jan 16th 2019 - Aurelien Illumination: What is light ? Wave Particle NIF Optical Seminar Jan 16th 2019 - Aurelien Light as a wave: properties Intensity I α A2 Wavelength (λ) Frequency ν=λ/c Amplitude (A) z direction of propagation Phase (φ) π/2 z0 t1203 π 0 z 3π/2 NIF Optical Seminar Jan 16th 2019 - Aurelien Light as a wave: properties LINEAR POLARIZATION CIRCULAR POLARIZATION ELLIPTICAL POLARIZATION Polarization becomes crucial for techniques such as DIC or if you use lasers as an illumination source. NIF Optical Seminar Jan 16th 2019 - Aurelien Light as a particle: why ? "It seems as though we must use sometimes the one theory and sometimes the other, while at times we may use either. (…) We have two contradictory pictures of reality; separately neither of them fully explains the phenomena of light, but together they do" PHOTOELECTRIC EFFECT Frequency threshold : below this threshold, no electrons are emitted, even if intensity is increased e e e BUT METAL Light propagates as discrete packets of energy called PHOTONS: Wave theory of light: increasing either the frequency or the intensity of light would increase electron Energy = hν h: Plank’s constant emission rate NIF Optical Seminar Jan 16th 2019 - Aurelien Light interactions Law of reflection: θ1 θ1' θ = θ ’ Reflection 1 1 n1 n2 θ2 n1 < n2 Law of refraction (Snell’s law): n1 sinθ1 = n2 sinθ2 Multicolor Refraction (n is dependent on n1 = c/v1, n2=c/v2 λ) is called dispersion Refraction NIF Optical Seminar Jan 16th 2019 - Aurelien Diffraction π/2 π 0 3π/2 constructive interference 0-2π destructive interference π intermediate interference π/2 Superposition of light waves generates interference patterns. -

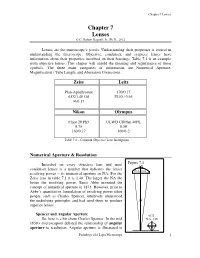

Chapter 7 Lenses

Chapter 7 Lenses Chapter 7 Lenses © C. Robert Bagnell, Jr., Ph.D., 2012 Lenses are the microscope’s jewels. Understanding their properties is critical in understanding the microscope. Objective, condenser, and eyepiece lenses have information about their properties inscribed on their housings. Table 7.1 is an example from objective lenses. This chapter will unfold the meaning and significance of these symbols. The three main categories of information are Numerical Aperture, Magnification / Tube Length, and Aberration Corrections. Zeiss Leitz Plan-Apochromat 170/0.17 63X/1.40 Oil Pl 40 / 0.65 ∞/0.17 Nikon Olympus Fluor 20 Ph3 ULWD CDPlan 40PL 0.75 0.50 160/0.17 160/0-2 Table 7.1 – Common Objective Lens Inscriptions Numerical Aperture & Resolution Figure 7.1 Inscribed on every objective lens and most 3 X condenser lenses is a number that indicates the lenses N.A. 0.12 resolving power – its numerical aperture or NA. For the Zeiss lens in table 7.1 it is 1.40. The larger the NA the better the resolving power. Ernst Abbe invented the concept of numerical aperture in 1873. However, prior to Abbe’s quantitative formulation of resolving power other people, such as Charles Spencer, intuitively understood the underlying principles and had used them to produce 1 4˚ superior lenses. Spencer and Angular Aperture 95 X So, here is a bit about Charles Spencer. In the mid N.A. 1.25 1850's microscopists debated the relationship of angular aperture to resolution. Angular aperture is illustrated in 110˚ Pathology 464 Light Microscopy 1 Chapter 7 Lenses figure 7.1.