Ignacio Ellacuría: the Ideal of a Radical Christian Intellectual William C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karl Rahner and Liberation Theology

KARL RAHNER AND LIBERATION THEOLOGY Jon Sobrino URING THE 1970s, A NEW CHURCH AND A NEW THEOLOGY arose in DLatin America. This article is a personal reflection on what Karl Rahner has meant for me in that context, though I hope that what I say will apply to liberation theology more broadly. I write out of the life-experience in El Salvador that has led me to read with new eyes the theology I had previously studied, in which Rahner’s work was a very important element. I am also writing out of my close personal and intellectual relationship with Ignacio Ellacuría, Rahner’s student in Innsbruck between 1958 and 1962. On account of his defence of faith and justice, Ellacuría, as many will know, was murdered on 16 November 1989, along with five other Jesuits and two female workers from the university in which he taught. But we should remember that Ellacuría was not just Rahner’s pupil. He took forward important ideas in Rahner’s theology, as he sought to express them in his own historical situation and in a way appropriate for the world of the poor. This article begins with an account of Rahner’s attitude towards the new things that were happening ecclesially and theologically in Latin America during the last years of his life. Then I shall try to explore Rahner’s influence on liberation theology. The Demands of a New Situation In an interview he gave to a Spanish magazine shortly before his death, Rahner was asked what he thought about the current state of the Church. -

Solidarity As Spiritual Exercise: a Contribution to the Development of Solidarity in the Catholic Social Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eScholarship@BC Solidarity as spiritual exercise: a contribution to the development of solidarity in the Catholic social tradition Author: Mark W. Potter Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/738 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2009 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Theology SOLIDARITY AS SPIRITUAL EXERCISE: A CONTRIBUTION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOLIDARITY IN THE CATHOLIC SOCIAL TRADITION a dissertation by MARK WILLIAM POTTER submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 © copyright by MARK WILLIAM POTTER 2009 Solidarity as Spiritual Exercise: A Contribution to the Development of Solidarity in the Catholic Social Tradition By Mark William Potter Director: David Hollenbach, S.J. ABSTRACT The encyclicals and speeches of Pope John Paul II placed solidarity at the very center of the Catholic social tradition and contemporary Christian ethics. This disserta- tion analyzes the historical development of solidarity in the Church’s encyclical tradition, and then offers an examination and comparison of the unique contributions of John Paul II and the Jesuit theologian Jon Sobrino to contemporary understandings of solidarity. Ultimately, I argue that understanding solidarity as spiritual exercise integrates the wis- dom of John Paul II’s conception of solidarity as the virtue for an interdependent world with Sobrino’s insights on the ethical implications of Christian spirituality, orthopraxis, and a commitment to communal liberation. -

The Legacy of the Jesuit Martyrs

AN EXAMINATION OF CATHOLIC IDENTITY AND IGNATIAN CHARACTER IN JESUIT HIGHER explore EDUCATION P UBLISHED BY THE I GNATIAN C ENTER AT S ANTA C LARA U NIVERSITY FALL 2009 VOL. 13 NO. 1 The Legacy of the Jesuit Martyrs 4 Why Were They Killed? 14 El Salvador 20 Rising to the 20 Years Later Martyrs’ Challenge FALL 2009 P UBLISHED BY THE I GNATIAN C ENTER FOR J ESUIT E DU C ATION AT S A N TA C LARA U NIVERSITY Peter Thamer ’08 F ROM THE C ENTER D IRE C TOR Kevin P. Quinn, S.J. Executive Director n the early hours of Nov. 16, 1989, six Jesuit priests, their Paul Woolley housekeeper, and her teenage daughter were brutally Associate Director I murdered by Salvadoran soldiers on the campus of the University of Central America (UCA) in San Salvador, El Salvador. Elizabeth Kelley Gillogly ’93 Managing Editor For speaking truth to power in war-ravaged El Salvador, for defending the poorest of the poor, and for ultimately promoting Amy Kremer Gomersall ’88 Design a faith that does justice without qualification, these Jesuits were considered traitors by certain members of El Salvador’s elite and Ignatian Center Advisory Board so were summarily executed. The 20th anniversary of the Jesuit Margaret Bradshaw Simon Chin assassinations offers an important opportunity to reflect on the Paul Crowley, S.J. enduring legacy of the martyrs and to ask what this legacy could Michael Engh, S.J. mean for Santa Clara University and for Jesuit higher education in Frederick J. Ferrer the early 21st century. -

CHRISTIANITY and SOCIETY the Liberation Theology in the Writings of Jon Sobrino and the Christian Realism of Reinhold Niebuhr

VID SPECIALIZED UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MISSION AND THEOLOGY CHRISTIANITY AND SOCIETY The Liberation Theology in the Writings of Jon Sobrino and the Christian Realism of Reinhold Niebuhr Master Thesis MTHEOL-342 By Francisco Sabotsy Directed by Prof. Knut Alfsvåg Stavanger, Norway June 2019 ii Dedicated to the Malagasy Christian Church in Norway (FKMN). iii Acknowledgment I have led you forty years in the wilderness: your clothes are not worn out upon you, and your shoes are not worn out upon your foot…that you might know that I am the LORD your God. (Deut 29:4-5) That reference is quoted here for the acknowledgment. Above all, I am deeply thankful to God that by the direction of the Holy Spirit I could write this thesis. Likewise, I also thank my precious Lord Jesus, not only for His help for the writing of this book but also for all the support He has granted me during the two year-study here at VID Specialized University. Glory be to God alone. My thanks go to the Malagasy Lutheran Church (MLC) for allowing me through the Lutheran Graduate School of theology (SALT) to continue my study here at VID. I thank VID as such, which is headed by Dean Dr. Tomas Sundnes Drønen, as it is the academic University where I pursued my theological study for two years. I particularly thank my supervisor, Prof. Knut Alfsvåg, lecturer in the Department of systematic theology as he directed me during the research. I am grateful to all the teachers here at VID for their lectures during the two academic years. -

The Witness of the Central American Martyrs: a Social Justice Aesthetic at U.S

The Witness of the Central American Martyrs: A Social Justice Aesthetic at U.S. Jesuit Colleges and Universities Tim Dulle Jr. U.S. Catholic Historian, Volume 39, Number 3, Summer 2021, pp. 105-126 (Article) Published by The Catholic University of America Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/cht.2021.0019 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/800036 [ Access provided at 16 Aug 2021 18:15 GMT from Xavier University ] The Witness of the Central American Martyrs: A Social Justice Aesthetic at U.S. Jesuit Colleges and Universities Tim Dulle, Jr.* In 1989 the Salvadoran military murdered six Jesuit priests and two of their companions at the Universidad Centroamericana (UCA), the Jesuit university in San Salvador. The killings ignited international protests, and the victims, well-known for their advocacy of human rights and social justice, quickly became celebrated martyrs. The Jesuits of the United States, who maintained a strong relationship with their Central American coun- terparts, were especially active in mobilizing their network in remem- brance of the UCA martyrs. In the decades since their deaths, these figures have become important symbols representing a social justice vision for Jesuit higher education in the U.S. The network’s members often made use of aes- thetic commemorations to invite others into the martyrs’ ongoing legacy, thereby staking a position in the ongoing contest concerning the soul of U.S. Catholic higher education. Keywords: Society of Jesus; Jesuits; Catholic higher education; social jus- tice; visual culture; El Salvador; Ellacuría, Ignacio, S.J.; Universidad Centroamericana; Rockhurst University; Xavier University; Ignatian Solidarity Network uring the early hours of November 16, 1989, the Salvadoran mili- D tary murdered six Jesuits and two companions at the Universidad Centroamericana (UCA) in San Salvador. -

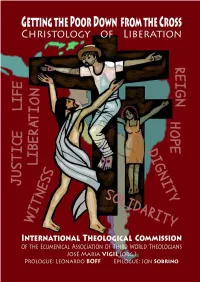

Getting the Poor Down from the Cross: a Christology of Liberation

GETTING THE POOR DOWN FROM THE CROSS Christology of Liberation International Theological Commission of the ECUMENICAL ASSOCIATION OF THIRD WORLD THEOLOGIANS EATWOT GETTING THE POOR DOWN FROM THE CROSS Christology of Liberation José María VIGIL (organizer) International Teological Commission of the Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians EATWOT / ASETT Second Digital Edition (Version 2.0) First English Digital Edition (version 1.0): May 15, 2007 Second Spanish Digital Edition (version 2.0): May 1, 2007 Frist Spanish Digital Edition (version 1.0): April 15, 2007 ISBN - 978-9962-00-232-1 José María VIGIL (organizer), International Theological Commission of the EATWOT, Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians, (ASETT, Asociación Ecuménica de Teólogos/as del Tercer Mundo). Prologue: Leonardo BOFF Epilogue: Jon SOBRINO Cover & poster: Maximino CEREZO BARREDO © This digital book is the property of the International Theological Commission of the Association of Third World Theologians (EATWOT/ ASETT) who place it at the disposition of the public without charge and give permission, even recommend, its sharing, printing and distribution without profit. This book can be printed, by «digital printing», as a professionally formatted and bound book. Software can be downloaded from: http://www.eatwot.org/TheologicalCommission or http://www.servicioskoinonia.org/LibrosDigitales A 45 x 65 cm poster, with the design of the cover of the book can also be downloaded there. Also in Spanish, Portuguese, German and Italian. A service of The International Theological Commission EATWOT, Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians (ASETT, Asociación Ecuménica de Teólogos/as del Tercer Mundo) CONTENTS Prologue, Getting the Poor Down From the Cross, Leonardo BOFF . -

Robert Lassalle-Klein, Blood and Ink: Ignacio Ellacuria, Jon Sobrino, and the Jesuit Martyrs of the University of Central America

Journal of Hispanic / Latino Theology Volume 21 Number 2 Article 6 11-1-2019 Robert Lassalle-Klein, Blood and Ink: Ignacio Ellacuria, Jon Sobrino, and the Jesuit Martyrs of the University of Central America Ramon Luzarraga Benedictine University Mesa Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/jhlt Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Luzarraga, Ramon "Robert Lassalle-Klein, Blood and Ink: Ignacio Ellacuria, Jon Sobrino, and the Jesuit Martyrs of the University of Central America," Journal of Hispanic / Latino Theology: Vol. 21 : No. 2 , Article 6. (2019) :177-180 Available at: https://repository.usfca.edu/jhlt/vol21/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Hispanic / Latino Theology by an authorized editor of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Luzarraga: Blood and Ink Robert Lassalle-Klein. Blood and Ink: Ignacio Ellacuría, Jon Sobrino, and the Jesuit Martyrs of the University of Central America. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2014. 376 pp. $34.00 Paper. ISBN: 978-1-62698-063-1. Robert Lassalle-Klein presents an intellectual history of the development of Latin American liberation theology at one of the centers of this development, El Salvador. His is also a work of intellectual archeology in which he exposes the manifold layers of this theology’s composition and the diverse cultural, ecclesiological, historical, philosophical, political, spiritual, and theological sources that informed its development. -

Characteristics of Jesuit Education------5

THE CHARACTERISTICS OF JESUIT EDUCATION TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Nº Introduction--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 The Characteristics of Jesuit Education------------------------------------------------------------ 5 Introductory Notes --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 1. Jesuit Education is world-affirming.---------------------------------------------------------- 7 radical goodness of the world a sense of wonder and mystery 2. Jesuit Education assists in the total formation of each individual within the human community.---------------------------------------- 7 the fullest development of all talents: intellectual imaginative, affective, and creative effective communication skills physical the balanced person within community 3. Jesuit Education includes a religious dimension that permeates the entire education.-------------------------------------------------------- 8 religious education development of a faith response which resists secularism worship of God and reverence for creation 4. Jesuit Education is an apostolic instrument.------------------------------------------------- 9 preparation for life 5. Jesuit Education promotes dialogue between faith and culture ---------------------------- 9 --------- 6. Jesuit Education insists on individual care and concern for each person.--------------------------------------------------------------- 10 developmental stages of growth curriculum centered on the person personal relationships -

Feminism and the Emerging Nation in El Salvador Emily Anderson Regis University

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2011 Feminism and the Emerging Nation in El Salvador Emily Anderson Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Emily, "Feminism and the Emerging Nation in El Salvador" (2011). All Regis University Theses. 529. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/529 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University Regis College Honors Theses Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. It is available only for research purposes and may not be used in violation of copyright laws or for unlawful purposes. -

Jon Sobrino's Liberation Christology and Its Implication For

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-11-2018 Jon Sobrino’s Liberation Christology and Its Implication for the “Crucified eopleP ” of the Niger Delta Region in Nigeria. Augustine Wayii Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Wayii, A. (2018). Jon Sobrino’s Liberation Christology and Its Implication for the “Crucified People” of the Niger Delta Region in Nigeria. (Master's thesis, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1431 This One-year Embargo is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JON SOBRINO’S LIBERATION CHRISTOLOGY AND ITS IMPLICATION FOR THE “CRUCIFIED PEOPLE” OF THE NIGER DELTA REGION IN NIGERIA. A Thesis Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theology By Augustine Lezorgia Wayii May 2018 Copyright by Augustine Lezorgia Wayii 2018 JON SOBRINO’S LIBERATION CHRISTOLOGY AND ITS IMPLICATION FOR THE “CRUCIFIED PEOPLE” OF THE NIGER DELTA REGION IN NIGERIA. By Augustine Lezorgia Wayii Approved March 26, 2018 ________________________________ ________________________________ Elisabeth T. Vasko. Ph.D. Elochukwu Uzukwu. Ph.D. Associate Professor of Theology Professor of Theology (Thesis Director) (Thesis Reader) ________________________________ ________________________________ James P. Swindal. Ph.D. Marinus Chijioke Iwuchukwu. Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate Department Chair School of Liberal Art Associate Professor of Theology iii ABSTRACT JON SOBRINO’S LIBERATION CHRISTOLOGY AND ITS IMPLICATION FOR THE “CRUCIFIED PEOPLE” OF THE NIGER DELTA REGION IN NIGERIA. -

? K in P. Q Inn, Sj

IS A DIFFERENTIFFERENT KINDIND OFOF JESUITESUIT UNIVERSITYNIVERSITY POSSIBLEOSSIBLE TODAYODAY? THEHE LEGACYEGACY OFOF IGNACIOGNACIO ELLACURÍALLACURÍA, SJSJ KEVINEVIN P. QUINNINN, SJSJ FOREWORDFOREWORRD BY ROBERTROBERT LLASSALLE-KLEIN,ASSALLE-KKLEIN, PHD 53/1 SPRING 2021 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits is a publication of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States. The Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality is composed of Jesuits appointed from their provinces. The seminar identifies and studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially US and Canadian Jesuits, and gath- ers current scholarly studies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. It then disseminates the results through this journal. The opinions expressed in Studies are those of the individual authors. The subjects treated in Studies may be of interest also to Jesuits of other regions and to other religious, clergy, and laity. All who find this journal helpful are welcome to access previous issues at: [email protected]/jesuits. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR Note: Parentheses designate year of entry as a seminar member. Casey C. Beaumier, SJ, is director of the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Stud - ies, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. (2016) Brian B. Frain, SJ, is Assistant Professor of Education and Director of the St. Thomas More Center for the Study of Catholic Thought and Culture at Rockhurst University in Kansas City, Missouri. (2018) Barton T. Geger, SJ, is chair of the seminar and editor of Studies; he is a research scholar at the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies and assistant professor of the practice at the School of Theology and Ministry at Boston College. -

Jesus of Galilee from the Salvadoran Context: Compassion, Hope, and Following the Light of the Cross

Theological Studies 70 (2009) JESUS OF GALILEE FROM THE SALVADORAN CONTEXT: COMPASSION, HOPE, AND FOLLOWING THE LIGHT OF THE CROSS JON SOBRINO, S.J. Translated by Robert Lassalle-Klein with J. Matthew Ashley The article analyzes a threefold isomorphism between the realities of Galilee and El Salvador: (1) the two realities are subjugated by imperial powers (2) the isomorphism least mentioned by com- mentators—between Jesus and the Salvadoran martyrs; and (3) the isomorphism between Jesus and the crucified people understood as the Servant of Yahweh who brings salvation. The article then considers three central realities—mercy, hope, and following—in light of the cross, Jesus, and the people. HIS ARTICLE RESPONDS to a request for a reflection on Jesus of Galilee Tfrom the perspective of El Salvador. The fundamentals of what I have to say have already been set out, for better or worse, in two books: Jesu- cristo liberador: Lectura teolo´gica de Jesu´s de Nazaret (1991) and La fe en Jesucrist:. Ensayo desde las vı´ctimas (1999). In these books I have tried to deal from the perspective of faith with the totality of the life and destiny of Jesus and with his ultimate reality. Here I will concentrate on certain elements that, while central to the Gospels, I see as especially clarified by the Salvadoran context. The task of selecting these fundamental elements is not simple. I will take the cross into special account, not only because the Gospels are “a passion narrative with an extended introduction” (Martin Ka¨hler, 1896),1 but be- cause the Salvadoran context is, above all else, the reality of “a crucified people” (Archbishop Oscar Romero, Ignacio Ellacurı´a).