Stamford in the Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ketton Village Walk September 2010 (Updated 2020)

Rutland Local History & Record Society Registered Charity No. 700273 Ketton Village Walk September 2010 (updated 2020) Copyright © Rutland Local History and Record Society All rights reserved INTRODUCTION The centre of the village contains many excellent buildings constructed with the famous butter‑coloured Ketton limestone which has been quarried locally since the Middle Ages. Ketton limestone is a 'freestone' because it can be worked in any direction. It is regarded as the perfect example of oolitic limestone. Many of the stone buildings are roofed in Collyweston slates. These frost-split slates have been extracted from shallow mines at Collyweston and Easton on the Hill just The Priory about 1925. (Jack Hart Collection) across the Valley from Ketton. This walk has been prepared from notes left by the late Geoff Fox and the late Jeffrey Smith, with some additions. THE VILLAGE MAP The map attached to this guided walk is based on the 25 inch to one mile Ordnance Survey 2nd edition map of 1899. Consequently, later buildings, extensions and demolitions are not shown. Numbers in the text, e.g. [12], refer to locations shown on the maps. Please: Respect private property. Use pavements and footpaths where available. Take great care when crossing roads. The church lychgate about 1925. (Jack Hart Collection) Remember that you are responsible for your own safety. The lychgate, of English oak and roofed with Collyweston slates, was erected by George Hibbins, THE WALK stonemason of Ketton, in 1909. This is a circular walk which starts and finishes at the Pass through the lychgate and walk to the Railway Inn. -

Unclassified Fourteenth- Century Purbeck Marble Incised Slabs

Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, No. 60 EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS This book is published with the generous assistance of The Francis Coales Charitable Trust. EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS Sally Badham and Malcolm Norris The Society of Antiquaries of London First published 1999 Dedication by In memory of Frank Allen Greenhill MA, FSA, The Society of Antiquaries of London FSA (Scot) (1896 to 1983) Burlington House Piccadilly In carrying out our study of the incised slabs and London WlV OHS related brasses from the thirteenth- and fourteenth- century London marblers' workshops, we have © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1999 drawn very heavily on Greenhill's records. His rubbings of incised slabs, mostly made in the 1920s All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, and 1930s, often show them better preserved than no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval they are now and his unpublished notes provide system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, much invaluable background information. Without transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, access to his material, our study would have been less without the prior permission of the copyright owner. complete. For this reason, we wish to dedicate this volume to Greenhill's memory. ISBN 0 854312722 ISSN 0953-7163 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the -

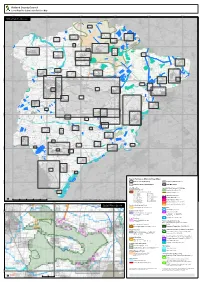

Rutland Main Map A0 Portrait

Rutland County Council Local Plan Pre-Submission Policies Map 480000 485000 490000 495000 500000 505000 Rutland County - Main map Thistleton Inset 53 Stretton (west) Clipsham Inset 51 Market Overton Inset 13 Inset 35 Teigh Inset 52 Stretton Inset 50 Barrow Greetham Inset 4 Inset 25 Cottesmore (north) 315000 Whissendine Inset 15 Inset 61 Greetham (east) Inset 26 Ashwell Cottesmore Inset 1 Inset 14 Pickworth Inset 40 Essendine Inset 20 Cottesmore (south) Inset 16 Ashwell (south) Langham Inset 2 Ryhall Exton Inset 30 Inset 45 Burley Inset 21 Inset 11 Oakham & Barleythorpe Belmesthorpe Inset 38 Little Casterton Inset 6 Rutland Water Inset 31 Inset 44 310000 Tickencote Great Inset 55 Casterton Oakham town centre & Toll Bar Inset 39 Empingham Inset 24 Whitwell Stamford North (Quarry Farm) Inset 19 Inset 62 Inset 48 Egleton Hambleton Ketton Inset 18 Inset 27 Inset 28 Braunston-in-Rutland Inset 9 Tinwell Inset 56 Brooke Inset 10 Edith Weston Inset 17 Ketton (central) Inset 29 305000 Manton Inset 34 Lyndon Inset 33 St. George's Garden Community Inset 64 North Luffenham Wing Inset 37 Inset 63 Pilton Ridlington Preston Inset 41 Inset 43 Inset 42 South Luffenham Inset 47 Belton-in-Rutland Inset 7 Ayston Inset 3 Morcott Wardley Uppingham Glaston Inset 36 Tixover Inset 60 Inset 58 Inset 23 Barrowden Inset 57 Inset 5 Uppingham town centre Inset 59 300000 Bisbrooke Inset 8 Seaton Inset 46 Eyebrook Reservoir Inset 22 Lyddington Inset 32 Stoke Dry Inset 49 Thorpe by Water Inset 54 Key to Policies on Main and Inset Maps Rutland County Boundary Adjoining -

Ketton Conservation Area

Ketton Conservation Area Ketton Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan Draft for consultation August 2019 1 1.0 Background Ketton conservation area was designated in 1972, tightly drawn around the historic core of Church Road, Chapel Lane, Redmiles Lane, Aldgate and Station Road and extended in 1975 to its current size. 2.0 Location and Setting Ketton is a large village located 4 miles south west of Stamford on the Stamford Road (A6121). It has been identified within the Rutland Landscape Character Assessment (2003) as being within the ‘Middle Valley East’ of the ‘Welland Valley’ character area which is ‘a relatively busy, agricultural, modern landscape with many settlements and distinctive valley profiles.’ The river Chater is an important natural feature of the village and within the valley are a number of meadow areas between Aldgate and Bull Lane that contribute towards the rural character of the conservation area. The south western part of the conservation area is particularly attractive with a number of tree groups at Ketton Park, the private grounds of the Priory and The Cottage making a positive contribution. The attractive butter coloured stone typical of Ketton is an important feature of the village. The stone quarry and cement works which opened in 1928 is located to the north. A number of famous buildings have been built out of Ketton Stone, such as Burghley House and many of the Cambridge University Colleges. Although the Parish Church is of Barnack stone. The historic core is nestled in the valley bottom on the north side of the River Chater and extends in a linear form along the High Street, continuing onto Stamford Road (A6121). -

A Late Roman Coin Hoard and Burials, Garley's Field, Ketton, Rutland Pp

A LATE ROMAN COIN HOARD AND BURIALS, GARLEY’S FIELD, KETTON, RUTLAND 2002–2003 Simon Carlyle Other contributors: Trevor Anderson, Mark Curteis, Roy Friendship-Taylor, Tora Hylton In March 2002, a Late Roman coin hoard and human remains were discovered during the mechanical excavation of an agricultural drainage sump in Garley’s Field, Ketton, Rutland. Following an initial examination and assessment of the site by Northamptonshire Archaeology and officers of the Leicestershire Museums, Arts and Records Service, funding was sought from English Heritage to carry out an archaeological investigation to excavate fully the disturbed burials and to examine the surrounding area for evidence of further archaeological remains. The programme of work, which was carried out by Northamptonshire Archaeology between August 2002 and January 2003, comprised remedial excavation and metal detecting, geophysical and fieldwalking surveys. The excavation and metal detecting survey resulted in the identification of five graves, including the one that had been completely destroyed by the machine excavation that led to the discovery of the site. The remains of at least 11 inhumation burials were recovered, along with evidence that at least three of the graves had been re-used. Three bracelets, one of shale and two of copper alloy, and two pottery accessory vessels were recovered from two of the graves, providing a date for the burials from the 3rd century onward. A further 326 coins were also found, increasing the total number of coins and coin fragments from the hoard to 1,418. The hoard had been deposited in one of the graves, either at the time of burial or perhaps as a later insertion. -

New Electoral Arrangements for Rutland County Council

New electoral arrangements for Rutland County Council Final recommendations April 2018 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] © The Local Government Boundary Commission for England 2018 The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2018 Table of Contents Summary .................................................................................................................... 1 Who we are and what we do .................................................................................. 1 Electoral review ...................................................................................................... 1 Why Rutland? ......................................................................................................... 1 Our proposals for Rutland ....................................................................................... 1 What is the Local Government Boundary Commission for England? ......................... 2 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 3 What is an electoral review? .................................................................................. -

Ketton Parish Council Agenda

M I N U T E S O F M E E T I N G Minutes of the Full Council Meeting of Ketton Parish Council held on Wednesday, July 17, 2019 in The Parish Office, Stocks Hill Lane, Ketton, STAMFORD, Lincolnshire, PE9 3TW, commencing at 7:30 pm. Present: Cllrs J. Rogers, S. Rogers, Cade, Southern, Eastwood, Couzens, Forster, County Cllrs Karen Payne & Gordon Brown & the Clerk 2019/07/01 To receive and approve Apologies for Absence Apologies were received from Cllrs Wright, Pick, Andrew, Warrington & Payne & approved. 2019/07/02 To receive Declarations of Interest, Dispensations and Additions to Registers [Section 27 Localism Act 2011] Declarations of Interest were received from Cllr Forster, who is the Treasurer of Ketton Cricket Club & St Mary’s Church, Ketton; Cllr J. Rogers, who is a KSCC trustee; Councillors Southern, who is a governor at Ketton School & KSCC trustee; Cllr S.Rogers, who is a governor of Edith Weston Academy and a trustee of the Brooke Hill Multi Academy Trust ; Cllr Cade, who is a member of the Ketton & Tinwell Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group & accepted. 2019/07/03 To approve and sign the Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting of June 19, 2019 Cllr Cade proposed that the minutes of June 19, 2019 were a true and accurate record, which was seconded by Cllr Couzens, and unanimously agreed by Council. The Minutes were approved and signed. 2019/07/04 To receive any Matters Arising for information exchange [NB Matters Arising may only appertain to the immediately preceding Parish Council Meetings - i.e. -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

Housing Supply Background Paper

Rutland Local Plan Review 2015-2036 Issues and Options Consultation Housing Supply Background Paper October 2015 1 Rutland Local Plan Review Issues and Options Consultation Housing Supply Background Paper (October 2015) Contents 1. Purpose............................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Explanation of figures .................................................................................................................. 3 Table 1 Explanation of housing figures ................................................................................................ 3 Table 2: Calculation of remaining dwelling requirement ................................................................... 5 Table 3: Allocated Sites .......................................................................................................................... 6 Table 4: Dwellings with planning permission/under construction .................................................... 7 Reference Documents .......................................................................................................................... 14 2 Rutland Local Plan Review Issues and Options Consultation Housing Supply Background Paper (October 2015) 1. Purpose 1.1. The purpose of this paper is to explain the calculation of the housing supply figures set out in Figure 4 of the Rutland Local Plan Review – Issues and Options Consultation document (November 2015). Figure 4 is set out below: Figure 4: -

Savills Lincoln & Stamford Home Truths

Savills Lincoln & Stamford Home Truths Tuesday 11 May 2021 Welcome and thank you for joining. You are on mute for the duration of the webinar. We will begin shortly. 1 Welcome James Abbott Faisal Choudhry Rupert Fisher Head of North East & East Residential Head of Residential Midlands Region Research Lincoln [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 07929 022 901 07967 555 720 07971 798 819 2 Q&A Panelists Charlotte Paton Tim Phillips Residential Sales Country House Stamford Department [email protected] [email protected] 07807 999 469 07870 867 218 3 Residential Market Outlook Faisal Choudhry - Residential Research 2020 anything but a normal housing market 1st modern-day Resulting in a recession where market driven by the economy those with and housing financial security market have rather than those moved in Government exposed to the different intervention on economic fallout directions jobs, earnings and Stamp Duty and a Low preceding benevolent price growth, approach to For whom a ultra-low interest mortgage reassessment of rates and early repayments housing needs expectations of a and priorities sharp V-shaped essentially recovery overrode marked it out as economics different 5 Exceptional market performance East Midlands market activity between June 2019 and April 2020 compared with June 2020 to April 2021 Net agreed sales Price reductions 160% 157% 140% 149% 120% 123% 100% 80% Apr Apr 2021 - 60% 70% Apr Apr 2020 versus - 40% 54% Jun Jun 2020 20% 30% 7% 17% 16% Jun Jun 2019 0% 1% -7% -20% -33% -40% -

Rutland 1871 Census Returns

CULPIN-net Census Finds for CULPIN in Rutland 1871 Estimat Surnam Relationshi Marital ed Birth Birth Residence Residence Sch Address Given Name Age Gender Occupation Birth City REF YEAR e p to Head Status Birth County Country Place County No Year Wood Northamp Ryhall William Calpin Head m 62 1809 Male Ag Lab England Ryhall Rutland RG10-3310 13 1871 Newton tonshire Northamp Ryhall Mary Calpin Wife m 57 1814 Female Elton England Ryhall Rutland RG10-3310 13 1871 tonshire Ag Lab Day Ryhall George Calpin Son 14 1857 Male Ryhall Rutland England Ryhall Rutland RG10-3310 13 1871 Boy Ryhall James Calpin Son 9 1862 Male Scholar Ryhall Rutland England Ryhall Rutland RG10-3310 13 1871 Empringham William Calpin Head 42 1829 Male Master Tailor Ketton Rutland England Empringham Rutland RG10-3299 66 1871 Manton Hosea Calpin Head 34 1837 Male Ketton Rutland England Empringham Rutland RG10-3300 8 1871 Manton Emma Calpin Wife 34 1837 Female Lyndon Rutland England Empringham Rutland RG10-3300 8 1871 Hosea Lincolnshi Manton Calpin Son 8 1863 Male Brigg England Empringham Rutland RG10-3300 8 1871 Silvanus re Dairy Edith Woman Nottingha Weston Abigail Calpin Head 63 1808 Female (retired) Thorston mshire England Edith Weston Rutland RG10-3299 69 1871 Edith Granddaught Weston Georgine Calpin er 12 1859 Female Scholar Oakham Rutland England Edith Weston Rutland RG10-3299 69 1871 Edith George Calpin Head 32 1839 Male Ag Lab Ketton Rutland England Edith Weston Rutland RG10-3299 69 1871 Weston Edith Mary Calpin Wife 32 1839 Female Morcott Rutland England Edith Weston -

To Rutland Record 21-30

Rutland Record Index of numbers 21-30 Compiled by Robert Ovens Rutland Local History & Record Society The Society is formed from the union in June 1991 of the Rutland Local History Society, founded in the 1930s, and the Rutland Record Society, founded in 1979. In May 1993, the Rutland Field Research Group for Archaeology & History, founded in 1971, also amalgamated with the Society. The Society is a Registered Charity, and its aim is the advancement of the education of the public in all aspects of the history of the ancient County of Rutland and its immediate area. Registered Charity No. 700723 The main contents of Rutland Record 21-30 are listed below. Each issue apart from RR25 also contains annual reports from local societies, museums, record offices and archaeological organisations as well as an Editorial. For details of the Society’s other publications and how to order, please see inside the back cover. Rutland Record 21 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 31 9 Letters of Mary Barker (1655-79); A Rutland association for Anton Kammel; Uppingham by the Sea – Excursion to Borth 1875-77; Rutland Record 22 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 32 7 Obituary – Prince Yuri Galitzine; Returns of Rutland Registration Districts to 1851 Religious Census; Churchyard at Exton Rutland Record 23 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 33 4 Hoard of Roman coins from Tinwell; Medieval Park of Ridlington;* Major-General Lord Ranksborough (1852-1921); Rutland churches in the Notitia Parochialis 1705; John Strecche, Prior of Brooke 1407-25