Modern History.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932'

EAST INDIA (CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS) REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932' Presented by the Secretary of State for India to Parliament by Command of His Majesty July, 1932 LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H^M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120, George Street, Edinburgh York Street, Manchester; i, St. Andrew’s Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1932 Price od. Net Cmd. 4103 A House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. The total cost of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) 4 is estimated to be a,bout £10,605. The cost of printing and publishing this Report is estimated by H.M. Stationery Ofdce at £310^ House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page,. Paras. of Members .. viii Xietter to Frim& Mmister 1-2 Chapter I.—^Introduction 3-7 1-13 Field of Enquiry .. ,. 3 1-2 States visited, or with whom discussions were held .. 3-4 3-4 Memoranda received from States.. .. .. .. 4 5-6 Method of work adopted by Conunittee .. .. 5 7-9 Official publications utilised .. .. .. .. 5. 10 Questions raised outside Terms of Reference .. .. 6 11 Division of subject-matter of Report .., ,.. .. ^7 12 Statistic^information 7 13 Chapter n.—^Historical. Survey 8-15 14-32 The d3masties of India .. .. .. .. .. 8-9 14-20 Decay of the Moghul Empire and rise of the Mahrattas. -

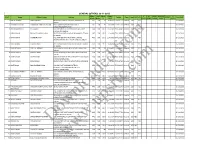

(OTHERS) 26-11-2018 Obtain Total Marks Date of a EX- ARDH MRATAK O S.NO

GENERAL (OTHERS) 26-11-2018 Obtain Total Marks Date of A EX- ARDH MRATAK O S.NO. Name Father's Name Address RefNo. Caste Amt NCC ITI RETIRE CALL DATE Marks Marks % Birth LEVEL ARMY SAINIK ASHRIT LEVEL 1 OMESH KUMAR RAM PRAKASH NEW BASTI, BANSHEEGOHARA, MAINPURI UP 465 500 93 16-Jul-93 ETW-19727 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 205001 2 SHIVAM CHAUHAN HANUMANT SINGH CHAUHAN POST GADHI RAMDHAN GADHI DALEL 465 500 93 1-Aug-00 ETW-21779 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 JASWANTNAGAR ETAWAH 3 ABHIMANYUSINGH RAJ KUMAR VILLAGE SARAY JALAL POST MANIYAMAU DIST 464 500 92.8 12-Jan-93 ETW-19384 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 ETAWAH PIN 206126 4 VIPIN KUMAR PRAKAS CHANDRA YADAV 33/623, SHAKUNTLA NAGAR, NEW MANDI, ETAWAH 463 500 92.6 4-Oct-89 ETW-19703 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 UP 206001 5 NITIN KUMAR AVDHESH SINGH VILL MUHABBATPUR POST SIRHAL TAHSIL 463 500 92.6 11-Feb-98 ETW-15582 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 JASWANTNAGAR DIST ETAWAH PINCODE 206245 6 VIVEK KUMAR KESHAV SINGH 229 FARRUKHABAD ROAD ASHOK NAGAR ETAWAH 462 500 92.4 10-Jul-90 ETW-19362 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 UP 206001 7 VIKAS PORWAL HOTI LAL PORWAL 310 KATRA BAL SINGH NEVIL ROAD ETAWAH PIN 460 500 92 30-Aug-86 ETW-19908 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 206001 8 SANJAY SINGH MANGAL SINGH LOHIYA WARD NO 6 VIDHUNA AURAIYA PIN CODE 458 500 91.6 2-Jul-98 ETW-18934 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 206243 from 9 AMIT KUMAR OM PRAKASH 186 JAIN MANDIR KE PAS KATRA FATEH MAHMOOD 456 500 91.2 10-Apr-88 ETW-20480 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 KHAN ETAWAH 206001 10 SANOJ KUMAR SURAJ SINGH ASHOK NAGAR, OLD PAC GALI, ETAWAH UP -

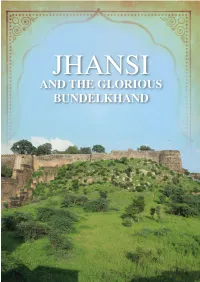

Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through the Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857?

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through The Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857? Attractions in and around Jhansi Jhansi Fort Rani Mahal Ganesh Mandir Mahalakshmi Temple Gangadharrao Chhatri Star Fort Jokhan Bagh St Jude’s Shrine Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery Jhansi Railway Station Orchha I N T R O D U C T I O N Jhansi is one of the most vibrant cities of Uttar Pradesh today. But the city is also steeped in history. The city of Rani Laxmibai - the brave queen who led her forces against the British in 1857 and the region around it, are dotted with monuments that go back more than 1500 years! While thousands of tourists visit Jhansi each year, many miss the layered past of the city. In fact, few who visit the famous Jhansi Fort each year, even know that it is in its historic Ganesh Mandir that Rani Laxmibai got married. Or that there is also a ‘second’ Fort hidden within the Jhansi cantonment, where the revolt of 1857 first began in the city. G L I M P S E S O F J H A N S I ’ S H I S T O R Y JHANSI THROUGH THE AGES Jhansi, the historic town and major tourist draw in Uttar Pradesh, is known today largely because of its famous 19th-century Queen, Rani Laxmibai, and the fearless role she played during the Revolt of 1857. There are also numerous monuments that dot Jhansi, remnants of the Bundelas and Marathas that ruled here from the 17th to the 19th centuries. -

Print Studio

11610001 11610002 GOVIND GOPAL DADHICH PARVINDER <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. KESHAV PRASHAD MISHRA SH. NARPAL 9414991727 8684883580 NEAR BY LAXMI NATH MANDIR, BHATTON KA V.P.O. BAWANIA , DSITT. MAHENDER GARH MOHALLA, WARD NO. 7, NEWAI, DISTT. TONK HARYANA RAJASTHAN 11610003 11610004 SHUBHAM KANSAL HARSHIT SINGH <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. NARESH KANSAL SH. HARIDWARI SINGH 9971705065 9411432741 1-H-47/A, NIT, FARIDABAD, HARYANA 46/7B- BUDDHI VIHAR, AVAS VIKAS, PHASE-11, MORADABAD 11610005 11610006 MANISH AMIT NAMA <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. LAXMI NARAYAN SH. GIRDHARI LAL NAMA 9541351727 9414726255 BABA KUNDI WARD NO. 17, STREET NO. 2 OLD 36 BAZIRPUR GATE KE ANDER, OLD VEGETABLE COURT ROAD NARWANA JIND MARKET, KARAULI 11610007 11610008 NIKITA GARG RAJESH <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. PARMOD GARG SH. MAHENDER SINGH 9416486505 9467844828 RAMCHANDRA PARMOD KUMAR, ANAJ MANDI H.NO. 62, NEAR GURUDWARA V.P.O. DHANGAR, LAHARU BHIWANI HARYANA DISTT FATEHABAD HARYANA 11610009 11610010 ABHISHEK SINGH SAHIL <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. SHIV PRAKASH SINGH SH. KHUSHI RAM 9919494263 9467743220 VILL. NAI GARHI DHARAWA POST. AMBERPUR, V.P.O. DHARAM KHERI, HANSI, DISTT. HISHAR, DISTT. SITAPUR, UP. HARYANA 11610011 11610012 SACHIN BABERWAL RISHABH ARORA <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. -

Name Capital Salute Type Existed Location/ Successor State Ajaigarh State Ajaygarh (Ajaigarh) 11-Gun Salute State 1765–1949 In

Location/ Name Capital Salute type Existed Successor state Ajaygarh Ajaigarh State 11-gun salute state 1765–1949 India (Ajaigarh) Akkalkot State Ak(k)alkot non-salute state 1708–1948 India Alipura State non-salute state 1757–1950 India Alirajpur State (Ali)Rajpur 11-gun salute state 1437–1948 India Alwar State 15-gun salute state 1296–1949 India Darband/ Summer 18th century– Amb (Tanawal) non-salute state Pakistan capital: Shergarh 1969 Ambliara State non-salute state 1619–1943 India Athgarh non-salute state 1178–1949 India Athmallik State non-salute state 1874–1948 India Aundh (District - Aundh State non-salute state 1699–1948 India Satara) Babariawad non-salute state India Baghal State non-salute state c.1643–1948 India Baghat non-salute state c.1500–1948 India Bahawalpur_(princely_stat Bahawalpur 17-gun salute state 1802–1955 Pakistan e) Balasinor State 9-gun salute state 1758–1948 India Ballabhgarh non-salute, annexed British 1710–1867 India Bamra non-salute state 1545–1948 India Banganapalle State 9-gun salute state 1665–1948 India Bansda State 9-gun salute state 1781–1948 India Banswara State 15-gun salute state 1527–1949 India Bantva Manavadar non-salute state 1733–1947 India Baoni State 11-gun salute state 1784–1948 India Baraundha 9-gun salute state 1549–1950 India Baria State 9-gun salute state 1524–1948 India Baroda State Baroda 21-gun salute state 1721–1949 India Barwani Barwani State (Sidhanagar 11-gun salute state 836–1948 India c.1640) Bashahr non-salute state 1412–1948 India Basoda State non-salute state 1753–1947 India -

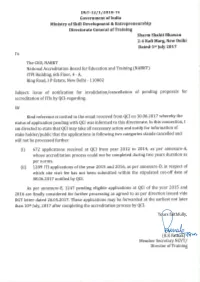

DGT Notification in Respect of Applications Prior to 2015-16

Annexure-A_Applications_Pending_for_more_than_2_years Sl. No. Application No. Name of the ITI and Address indicating town & District Name of State 1 App001123 SANMATI PRIVATE I T I, NEAR DALLU DAWTA SHAMLI Uttar Pradesh ROAD KHANJAHAPUR , DISTRICT: MUZAFFARNAGAR, STATE: UTTAR PRADESH, PIN CODE: 251002 2 App001125 GOVT. I.T.I. JHANSI., GWALIOR ROAD JHANSI. , DISTRICT: Uttar Pradesh JHANSI, STATE: UTTAR PRADESH, PIN CODE: 284003 3 App001126 CHAMPABEN BHAGAT EDU-COLLEGE OF FIRE Gujarat TECHNOLOGY, 86,VILL.KHODA,SANAND VIRAMGAM HIGHWAY , DISTRICT: AHMEDABAD, STATE: GUJARAT, PIN 4 App001128 GOVT. I.T.I., SUJROO CHUNGI , DISTRICT: Uttar Pradesh MUZAFFARNAGAR, STATE: UTTAR PRADESH, PIN CODE: 5 App001129 GITI ETAWAH, MAINPURI ROAD ETAWAH , DISTRICT: Uttar Pradesh ETAWAH, STATE: UTTAR PRADESH, PIN CODE: 206002 6 App001131 GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE BASTI, Uttar Pradesh KATARA BASTI , DISTRICT: BASTI, STATE: UTTAR PRADESH, 7 App001133 GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE, KHANTH Uttar Pradesh ROAD , DISTRICT: MORADABAD, STATE: UTTAR PRADESH, 8 App001136 GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE, Uttar Pradesh KARAUNDI, VARANASI , DISTRICT: VARANASI, STATE: UTTAR PRADESH, PIN CODE: 221005 9 App001140 GOVT. I.T.I. RAMPUR, GOVT. I.T.I. QILA CAMPUS RAMPUR , Uttar Pradesh DISTRICT: RAMPUR, STATE: UTTAR PRADESH, PIN CODE: 10 App001145 IJK PRIVATE ITI, PLOT NO 313 BISS FUTTA ROAD PREM Uttar Pradesh NAGAR LONI , DISTRICT: GHAZIABAD, STATE: UTTAR 11 App001146 GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE BALLIA, Uttar Pradesh RAMPUR UDYBHAN -

S.No DISTRICT ULB CODE CITY/ULB NAME NAME of BANK NAME of BRANCH IFSC CODE ADDRESS

BANK / BRANCHES OF UTTAR PRADESH MAPPED IN ALLAHABAD BANK PORTAL (www.allbankcare.in) S.No DISTRICT ULB CODE CITY/ULB NAME NAME OF BANK NAME OF BRANCH IFSC CODE ADDRESS 1 AGRA 800804 AGRA CANARA BANK IDGAH,AGRA CNRB0000194 41, NEW IDGAH COLONY, AGRA 282001 A 11 NEW AGRA NEAR BHAGWAN TALKIES AGRA UTTAR 2 AGRA 800804 AGRA SYNDICATE BANK AGRA DAYAL BAGH ROAD SYNB0009340 PRADESH 282005 3 AGRA 800804 AGRA STATE BANK OF INDIA TAJ GANJ SBIN0004537 FATEHABAD ROAD,AGRA, UTTAR PRADESH ,PIN - 282001 4 AGRA 800804 AGRA CANARA BANK HIG KI MANDI,AGRA CNRB0002144 BASANT BUILDING HINGKI MANDI,, AGRA 282003, 58173CP28B ADARSH NAGARARJUN NAGARKHEA AGRA 5 AGRA 800804 AGRA UNION BANK OF INDIA KHERIA MORE UBIN0575003 UTTAR PRADESH PINCODE282001 6 AGRA 800804 AGRA BANK OF INDIA KAMLA NAGAR (AGRA) BKID0007255 B - 61, MAIN ROADKAMLA NAGAR, AGRA, DAYAL BAGH ROAD, PATEL MARKET, DAYAL BAGH,DIST. 7 AGRA 800804 AGRA UNION BANK OF INDIA DAYAL BAGH UBIN0530565 AGRA, UTTAR PRADESH,PIN - 282 005. 8 AGRA 800804 AGRA STATE BANK OF INDIA BALKESHWAR COLONY, AGRA SBIN0003708 AGRA, U P, PIN 282004 9 AGRA 800804 AGRA CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA TAJGANJ CBIN0280236 TAJGANJ, AGRA POST BOX NO. 13,, 185\\185A SADAR BAZAR,, AGRA - 10 AGRA 800804 AGRA CANARA BANK AGRA CANTONMENT CNRB0000379 CANTONMENT 282001 11 AGRA 800804 AGRA CANARA BANK KENDRIYA HINDI SANSTHAN EC ,AGRA CNRB0003023 SHITLA ROAD AGRA UTTAR PRADESH 282002 12 AGRA 800804 AGRA CORPORATION BANK AGRA KAMLA NAGAR CORP0003190 D 527 KAMLA NAGAR AGRA 32,10, GUJAR TOPKHANA, LOHA MANDI,AGRA, U P,PIN 13 AGRA 800804 AGRA STATE BANK -

FORM - 1 District: Jalaun, State: Uttar Pradesh FORM- 1 Basic Information S

Project: River Bed Sand/ Moram Mining Proponent: Raghvendra Singh Gata No.1191/2, Khand No.03 Area: 20.242 Ha (49.99 Acre), River: Betwa, Village: Sikarivyas, Tehsil: Orai, FORM - 1 District: Jalaun, State: Uttar Pradesh FORM- 1 Basic Information S. No. Item Details 1. Name of the project/s Sand/Moram Mining 2. S. No. in the schedule 1(a)i 3. Proposed capacity/area/length/tonnage to Proposed Capacity: 2,02,420 cum/annum be handled / command and area/lease Area: 20.242 Ha (49.99 Acres) area/number of wells to be drilled. 4. New / Expansion / Modernization New Mine 5. Existing Capacity / Area etc. Not Applicable 6. Category of Project i.e. `A’ or `B’ Category “B2” 7. Does it attract the general condition? If yes, Not applicable please specify 8. Does it attract the specific condition? If yes, Not applicable please specify 9. Location Latitude : 25°46.160' N to 25°46.250' N Longitude : 79°19.349' E to 79°20.024' E River Betwa River Bed Plot / Survey / Khasra No. Gata No.1191/2, Khand No. 03 Village Sikarivyas Tehsil Orai District Jalaun State Uttar Pradesh 10. Nearest railway station / airport along with Railway Station: distance in km. Ait Railway Station 18 km NW Airport: Not Available 11. Nearest Town, city, District Headquarters Nearest Town: Orai 29.5 km, NE along with distance in km. Nearest City & District: Jalaun 42 km towards NW 12. Village Panchayats, Zilla Parishad, Gram Panchayat- Sikrivyas Municipal Corporation, Local body Zilla Panchayat - Jalaun (complete postal addresses with telephone nos. -

Or Government of India Act 1833 Was Passed by the British Parliament to Renew the Charter of East India Company Which Was Last Renewed in 1813

I. Short answers a) Charter Act 1833 (St. Helena Act) or Government of India Act 1833 was passed by the British Parliament to renew the charter of East India Company which was last renewed in 1813. Thereby charter was renewed for 20 years but the East India Company was deprived of its commercial privileges, so enjoyed. It legalized the British colonization of India and the territorial possessions of the company were allowed to remain under its government, but were held “in trust for his majesty, his heirs and successors” for the service of Government of India. The charter act of 1833 is considered to be an attempt to codify all the Indian Laws. The British parliament as a supreme body, retained the right to legislate for the British territories in India and repeal the acts. Further, this act provided that all laws made in India were to be laid before the British parliament and were to be known as Acts. In a step towards codifying the laws, an Indian law Commission was set up. b) The Swadeshi movement, part of the Indian independence movement and the developing Indian nationalism, was an economic strategy aimed at removing the British Empire from power and improving economic conditions in India by following the principles of swadeshi and which had some success. Strategies of the Swadeshi movement involved boycotting British products, the revival of domestic products and production processes. There was Widespread curbs on international and inter-state trade. The second Swadeshi movement started with the partition of Bengal by the Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon in 1905 and continued up to 1911. -

State Wise Teacher Education Institutions (Teis) and Courses(As on 31.03.2019) S.No

State wise Teacher Education Institutions (TEIs) and Courses(As on 31.03.2019) S.No. Name and Address of the Institution State Management Courses and Intake A B Alpsankhyak Shiksha Prasar Samiti, (Amtunna Bano Mahila Mahavidyalaya), Ramganj, Plot No.- 839, Village – Khade Dewar, Post Office – 1 Uttar Pradesh Private B.Ed. 100, D.El.Ed. 50 Gursahaiganj, Tehsil– Chhibramau, Dist.– Kannauj, Uttar Pradesh – 209722, Mobile No. 9415333650 A B R L Mahila Mahavidyalay, Plot/Khasara No. 4mi SA, Plot No. -0, Street 2 Number-0, Vill-Sadahara, Post Office- Oniya, Teh/Taluk- Dhanghta, Town/City- Uttar Pradesh Private B.Ed. 100, D.El.Ed. 100 0, Dist- Sant Kabit Nagar, State-UP, Pin-272176 A K Degree College, Plot no. 927KH, Street no. Chhibramau, Village- 3 Asalatabad, Post office – Asalatabad, Tehsil/Taluka – Chhibramau, District – Uttar Pradesh Private B.Ed. 50 Kannauj-209721, Uttar Pradesh. A K G College, Plot Number- 448, Street/Road- NA, Village/Town/City- Bika Mau Kala, Post Office- Bakshi Ka Talab, Tehsil/Taluka- Bakshi Ka Talab, 4 Uttar Pradesh Private B.Ed. 100, D.El.Ed. 50 Town/City- Lucknow, District- Lucknow(UP), State- Uttar Pradesh, Pin Code- 226201 A K Singh College, Plot No. 1131s, 1132, 1126s, 1129s, Village- Nagla Bari, 5 Uttar Pradesh Private D.El.Ed. 100 Post Office - Rustamgarh, Tehsil - Etah (UP) 207001 A M College of Higher Education, Plot Number– 227M, 248M, Street/Road– 227M, 248M, Village/Town/City- Basdeopur and Haweli, Post Office- Dhuriapar, 6 Uttar Pradesh Private D.El.Ed. 100 Tehsil/Taluka- Gola, Town/City- Gorkhpur, District- Gorkakhpur (UP), State– UP, Pin Code- 273200. -

The Virangana in North Indian History: Myth and Popular Culture Author(S): Kathryn Hansen Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol

The Virangana in North Indian History: Myth and Popular Culture Author(s): Kathryn Hansen Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 23, No. 18 (Apr. 30, 1988), pp. WS25-WS33 Published by: Economic and Political Weekly Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4378431 Accessed: 13/06/2009 19:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=epw. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Economic and Political Weekly is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Economic and Political Weekly. http://www.jstor.org The Virangana in North Indian istory Myth and Popular Culture Kathryn Hansen Thepattern of women'slives and their orientationto social realityare significantlyshaped by the models of womanlyconduct set out in stories, legends and songs preservedfrom the past. -

The Long-Term Impact of Colonial Rule: Evidence from India ∗

The Long-term Impact of Colonial Rule: Evidence from India ∗ Lakshmi Iyery JOB MARKET PAPER November 14, 2002 Abstract Does colonial rule affect long-term economic outcomes? I answer this question by comparing areas in India which were under direct control of British administrators with areas which were ruled by Indian rulers and only indirectly controlled by the colonial power. OLS results in this context are likely to be biased due to selection bias in British annexation. I take advantage of a specific annexation policy of the British to construct an instrumental variable estimate of the impact of colonial rule. I find evidence that colonial annexation policy was highly selective and concentrated on areas with high agricultural potential. The IV estimates show that areas under direct British rule have significantly lower levels of public goods in the present period. Data from earlier periods indicate that the public goods differences were present in the colonial period itself, and are narrowing over time in the post-Independence period. ∗I am grateful to Daron Acemoglu, Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo for valuable advice and guidance throughout this project. I thank Josh Angrist, Simon Johnson, Kaivan Munshi, Rohini Pande, Marko Tervi¨oand seminar participants at the Australian National University and the MIT Development and Organizational Economics lunches for extremely helpful comments. I also thank the MacArthur Foundation for financial support and Esther Duflo for generously sharing her code for the randomization inference procedure. yDepartment of Economics, MIT. [email protected] 1 Introduction The expansion of European empires starting at the end of the 15th century has been an important feature of world history.