The Colonial Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932'

EAST INDIA (CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS) REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932' Presented by the Secretary of State for India to Parliament by Command of His Majesty July, 1932 LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H^M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120, George Street, Edinburgh York Street, Manchester; i, St. Andrew’s Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1932 Price od. Net Cmd. 4103 A House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. The total cost of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) 4 is estimated to be a,bout £10,605. The cost of printing and publishing this Report is estimated by H.M. Stationery Ofdce at £310^ House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page,. Paras. of Members .. viii Xietter to Frim& Mmister 1-2 Chapter I.—^Introduction 3-7 1-13 Field of Enquiry .. ,. 3 1-2 States visited, or with whom discussions were held .. 3-4 3-4 Memoranda received from States.. .. .. .. 4 5-6 Method of work adopted by Conunittee .. .. 5 7-9 Official publications utilised .. .. .. .. 5. 10 Questions raised outside Terms of Reference .. .. 6 11 Division of subject-matter of Report .., ,.. .. ^7 12 Statistic^information 7 13 Chapter n.—^Historical. Survey 8-15 14-32 The d3masties of India .. .. .. .. .. 8-9 14-20 Decay of the Moghul Empire and rise of the Mahrattas. -

Myth, Language, Empire: the East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-10-2011 12:00 AM Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 Nida Sajid University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Nida Sajid 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Cultural History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Sajid, Nida, "Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 153. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/153 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 (Spine Title: Myth, Language, Empire) (Thesis format: Monograph) by Nida Sajid Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Nida Sajid 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners _____________________ _ ____________________________ Dr. -

MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 to the Present)

MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 to the Present) STUDY MATERIAL I / II SEMESTER HIS1(2)C01 Complementary Course of BA English/Economics/Politics/Sociology (CBCSS - 2019 ADMISSION) UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION Calicut University P.O, Malappuram, Kerala, India 673 635. 19302 School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION STUDY MATERIAL I / II SEMESTER HIS1(2)C01 : MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 TO THE PRESENT) COMPLEMENTARY COURSE FOR BA ENGLISH/ECONOMICS/POLITICS/SOCIOLOGY Prepared by : Module I & II : Haripriya.M Assistanrt professor of History NSS College, Manjeri. Malappuram. Scrutinised by : Sunil kumar.G Assistanrt professor of History NSS College, Manjeri. Malappuram. Module III&IV : Dr. Ancy .M.A Assistant professor of History School of Distance Education University of Calicut Scrutinised by : Asharaf koyilothan kandiyil Chairman, Board of Studies, History (UG) Govt. College, Mokeri. Modern Indian History (1857 to the present) Page 2 School of Distance Education CONTENTS Module I 4 Module II 35 Module III 45 Module IV 49 Modern Indian History (1857 to the present) Page 3 School of Distance Education MODULE I INDIA AS APOLITICAL ENTITY Battle Of Plassey: Consolodation Of Power By The British. The British conquest of India commenced with the conquest of Bengal which was consummated after fighting two battles against the Nawabs of Bengal, viz the battle of Plassey and the battle of Buxar. At that time, the kingdom of Bengal included the provinces of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. Wars and intrigues made the British masters over Bengal. The first conflict of English with Nawab of Bengal resulted in the battle of Plassey. -

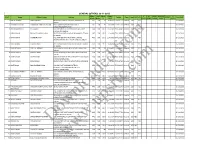

(OTHERS) 26-11-2018 Obtain Total Marks Date of a EX- ARDH MRATAK O S.NO

GENERAL (OTHERS) 26-11-2018 Obtain Total Marks Date of A EX- ARDH MRATAK O S.NO. Name Father's Name Address RefNo. Caste Amt NCC ITI RETIRE CALL DATE Marks Marks % Birth LEVEL ARMY SAINIK ASHRIT LEVEL 1 OMESH KUMAR RAM PRAKASH NEW BASTI, BANSHEEGOHARA, MAINPURI UP 465 500 93 16-Jul-93 ETW-19727 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 205001 2 SHIVAM CHAUHAN HANUMANT SINGH CHAUHAN POST GADHI RAMDHAN GADHI DALEL 465 500 93 1-Aug-00 ETW-21779 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 JASWANTNAGAR ETAWAH 3 ABHIMANYUSINGH RAJ KUMAR VILLAGE SARAY JALAL POST MANIYAMAU DIST 464 500 92.8 12-Jan-93 ETW-19384 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 ETAWAH PIN 206126 4 VIPIN KUMAR PRAKAS CHANDRA YADAV 33/623, SHAKUNTLA NAGAR, NEW MANDI, ETAWAH 463 500 92.6 4-Oct-89 ETW-19703 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 UP 206001 5 NITIN KUMAR AVDHESH SINGH VILL MUHABBATPUR POST SIRHAL TAHSIL 463 500 92.6 11-Feb-98 ETW-15582 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 JASWANTNAGAR DIST ETAWAH PINCODE 206245 6 VIVEK KUMAR KESHAV SINGH 229 FARRUKHABAD ROAD ASHOK NAGAR ETAWAH 462 500 92.4 10-Jul-90 ETW-19362 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 UP 206001 7 VIKAS PORWAL HOTI LAL PORWAL 310 KATRA BAL SINGH NEVIL ROAD ETAWAH PIN 460 500 92 30-Aug-86 ETW-19908 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 206001 8 SANJAY SINGH MANGAL SINGH LOHIYA WARD NO 6 VIDHUNA AURAIYA PIN CODE 458 500 91.6 2-Jul-98 ETW-18934 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 206243 from 9 AMIT KUMAR OM PRAKASH 186 JAIN MANDIR KE PAS KATRA FATEH MAHMOOD 456 500 91.2 10-Apr-88 ETW-20480 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 KHAN ETAWAH 206001 10 SANOJ KUMAR SURAJ SINGH ASHOK NAGAR, OLD PAC GALI, ETAWAH UP -

Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power

Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power Subject: History Unit: Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power Lesson: Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power Lesson Developer : Prof. Lakshmi Subramanian College/Department : Professor, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of Delhi Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power Table of contents Chapter 2: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power • 2.1: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power • Summary • Exercises • Glossary • Further readings Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of Delhi Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power 2.1: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Introduction The second half of the 18th century saw the formal induction of the English East India Company as a power in the Indian political system. The battle of Plassey (1757) followed by that of Buxar (1764) gave the Company access to the revenues of the subas of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and a subsequent edge in the contest for paramountcy in Hindustan. Control over revenues resulted in a gradual shift in the orientation of the Company’s agenda – from commerce to land revenue – with important consequences. This chapter will trace the development of the Company’s rise to power in Bengal, the articulation of commercial policies in the context of Mercantilism that developed as an informing ideology in Europe and that found limited application in India by some of the Company’s officials. This found expression until the 1750’s in the form of trade privileges, differential customs payments and fortifications of Company settlements all of which combined to produce an alternative nucleus of power within the late Mughal set up. -

British Imperialism in India

4 British Imperialism in India MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES EMPIRE BUILDING As the India, the second most • sepoy • Sepoy Mughal Empire declined, Britain populated nation in the world, •“jewel in Mutiny seized Indian territory and soon has its political roots in this the crown” • Raj controlled almost the whole colony. subcontinent. SETTING THE STAGE British economic interest in India began in the 1600s, CALIFORNIA STANDARDS when the British East India Company set up trading posts at Bombay, Madras, 10.4.1 Describe the rise of industrial and Calcutta. At first, India’s ruling Mughal Dynasty kept European traders economies and their link to imperialism and under control. By 1707, however, the Mughal Empire was collapsing. Dozens of colonialism (e.g., the role played by national security and strategic advantage; moral small states, each headed by a ruler or maharajah, broke away from Mughal con- issues raised by the search for national trol. In 1757, Robert Clive led East India Company troops in a decisive victory hegemony, Social Darwinism, and the mis- sionary impulse; material issues such as land, over Indian forces allied with the French at the Battle of Plassey. From that time resources, and technology). until 1858, the East India Company was the leading power in India. 10.4.3 Explain imperialism from the perspective of the colonizers and the colonized and the varied immediate and long-term responses by the people under British Expand Control over India colonial rule. The area controlled by the East India Company grew over time. Eventually, it 10.4.4 Describe the independence struggles governed directly or indirectly an area that included modern Bangladesh, most of the colonized regions of the world, including the roles of leaders, such as Sun of southern India, and nearly all the territory along the Ganges River in the north. -

Scaling of Mangrove Afforestation with Carbon

Field Actions Science Reports The journal of field actions Special Issue 7 | 2013 Livelihoods Scaling of mangrove afforestation with carbon finance to create significant impact on the biodiversity – a new paradigm in biodiversity conservation models Reforestation de la mangrove à grande échelle par la finance carbone pour un impact significatif sur la biodiversité – un nouveau paradigme parmi les modèles de conservation de la biodiversité Aumento de la reforestación de manglares con la financiación del carbono para crear un impacto significativo en la biodiversidad: un nuevo paradigma en los modelos de conservación de la biodiversidad Ajanta Dey and Animesh Kar Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/2674 ISSN: 1867-8521 Publisher Institut Veolia Electronic reference Ajanta Dey and Animesh Kar, « Scaling of mangrove afforestation with carbon finance to create significant impact on the biodiversity – a new paradigm in biodiversity conservation models », Field Actions Science Reports [Online], Special Issue 7 | 2013, Online since 19 April 2013, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/2674 Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License © Author(s) 2013. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. http://factsreports.revues.org/xxx Published xxx Scaling of mangrove afforestation with carbon finance to create significant impact on the biodiversity – a new paradigm in biodiversity conservation models Ajanta Dey1 and Animesh Kar2 1Joint Secretary and Project Director Nature Environment & Wildlife Society Member, CEM – IUCN and Associate Editor, Environ [email protected] 2Co-ordinator, Research and Monitoring Nature Environment & Wildlife Society [email protected] Abstract. Sunderbans has undergone a huge loss of forest cover in the past century. -

The Corporate Evolution of the British East India Company, 1763-1813

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Imperial Venture: The Evolution of the British East India Company, 1763-1813 Matthew Williams Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IMPERIAL VENTURE: THE EVOLUTION OF THE BRITISH EAST INDIA COMPANY, 1763-1813 By MATTHEW WILLIAMS A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 Matthew Richard Williams defended this thesis on October 11, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Thesis Jonathan Grant Committee Member James P. Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Rebecca iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. Rafe Blaufarb for his enthusiasm and guidance on this thesis, as well as agreeing to this topic. I must also thank Dr. Charles Cox, who first stoked my appreciation for history. I also thank Professors Jonathan Grant and James Jones for agreeing to participate on my committee. I would be remiss if I forgot to mention and thank Professors Neil Jumonville, Ron Doel, Darrin McMahon, and Will Hanley for their boundless encouragement, enthusiasm, and stimulating conversation. All of these professors taught me the craft of history. I have had many classes with each of these professors and enjoyed them all. -

Governor-General and Viceroy of India

www.gradeup.co Governor-General and Viceroy of India Governors of Bengal (1757–74) Robert Clive • Governor of Bengal during 1757–60 and again during 1765–67 and established Dual Government in Bengal from 1765–72. • Clive’s initial stay in India lasted from 1744 to 1753. • He was called back to India in 1755 to ensure British supremacy in the subcontinent against the French. • In 1757, Clive along with Admiral Watson was able to recapture Calcutta from the Nawab of Bengal Siraj Ud Daulah. • In the Battle of Plassey, the Nawab was defeated by the British despite having a larger force. • Clive ensured an English victory by bribing the Nawab’s army commander Mir Jaffar, who was installed as Bengal’s Nawab after the battle. • Clive was also able to capture some French forts in Bengal. • For these exploits, Robert Clive was made Lord Clive, Baron of Plassey. • As a result of this battle, the British became the paramount power in the Indian subcontinent. • Bengal became theirs and this greatly increased the company’s fortunes. (Bengal was richer than Britain at that time). • This also opened up other parts of India to the British and finally led to the rise of the British Raj in India. For this reason, Robert Clive is also known as “Conqueror of India”. • Vansittart (1760–65): The Battle of Buxar (1764). • Cartier (1769–72): Bengal Famine (1770). Governors-General of Bengal (1774–1833) Warren Hastings (1772–1785) • First Governor General of Bengal. • Brought the Dual Government of Bengal to an end by the Regulating Act, 1773 • Became Governor-General in 1774 through the Regulating Act, 1773. -

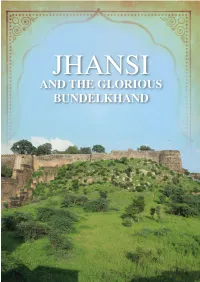

Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through the Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857?

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through The Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857? Attractions in and around Jhansi Jhansi Fort Rani Mahal Ganesh Mandir Mahalakshmi Temple Gangadharrao Chhatri Star Fort Jokhan Bagh St Jude’s Shrine Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery Jhansi Railway Station Orchha I N T R O D U C T I O N Jhansi is one of the most vibrant cities of Uttar Pradesh today. But the city is also steeped in history. The city of Rani Laxmibai - the brave queen who led her forces against the British in 1857 and the region around it, are dotted with monuments that go back more than 1500 years! While thousands of tourists visit Jhansi each year, many miss the layered past of the city. In fact, few who visit the famous Jhansi Fort each year, even know that it is in its historic Ganesh Mandir that Rani Laxmibai got married. Or that there is also a ‘second’ Fort hidden within the Jhansi cantonment, where the revolt of 1857 first began in the city. G L I M P S E S O F J H A N S I ’ S H I S T O R Y JHANSI THROUGH THE AGES Jhansi, the historic town and major tourist draw in Uttar Pradesh, is known today largely because of its famous 19th-century Queen, Rani Laxmibai, and the fearless role she played during the Revolt of 1857. There are also numerous monuments that dot Jhansi, remnants of the Bundelas and Marathas that ruled here from the 17th to the 19th centuries. -

Print Studio

11610001 11610002 GOVIND GOPAL DADHICH PARVINDER <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. KESHAV PRASHAD MISHRA SH. NARPAL 9414991727 8684883580 NEAR BY LAXMI NATH MANDIR, BHATTON KA V.P.O. BAWANIA , DSITT. MAHENDER GARH MOHALLA, WARD NO. 7, NEWAI, DISTT. TONK HARYANA RAJASTHAN 11610003 11610004 SHUBHAM KANSAL HARSHIT SINGH <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. NARESH KANSAL SH. HARIDWARI SINGH 9971705065 9411432741 1-H-47/A, NIT, FARIDABAD, HARYANA 46/7B- BUDDHI VIHAR, AVAS VIKAS, PHASE-11, MORADABAD 11610005 11610006 MANISH AMIT NAMA <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. LAXMI NARAYAN SH. GIRDHARI LAL NAMA 9541351727 9414726255 BABA KUNDI WARD NO. 17, STREET NO. 2 OLD 36 BAZIRPUR GATE KE ANDER, OLD VEGETABLE COURT ROAD NARWANA JIND MARKET, KARAULI 11610007 11610008 NIKITA GARG RAJESH <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. PARMOD GARG SH. MAHENDER SINGH 9416486505 9467844828 RAMCHANDRA PARMOD KUMAR, ANAJ MANDI H.NO. 62, NEAR GURUDWARA V.P.O. DHANGAR, LAHARU BHIWANI HARYANA DISTT FATEHABAD HARYANA 11610009 11610010 ABHISHEK SINGH SAHIL <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. SHIV PRAKASH SINGH SH. KHUSHI RAM 9919494263 9467743220 VILL. NAI GARHI DHARAWA POST. AMBERPUR, V.P.O. DHARAM KHERI, HANSI, DISTT. HISHAR, DISTT. SITAPUR, UP. HARYANA 11610011 11610012 SACHIN BABERWAL RISHABH ARORA <<dob>> <<dob>> B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year B.Te ch Civil Engineering (4 Year SH. -

Battle of Plassey, June 23 1757 - NCERT Notes on Modern Indian History for UPSC

Battle of Plassey, June 23 1757 - NCERT Notes on Modern Indian History for UPSC The Battle of Plassey was a major turning point in modern Indian history that led to the consolidation of the British rule in India. This battle was fought between the East India Company headed by Robert Clive and the Nawab of Bengal (Siraj-Ud-Daulah) and his French Troop. This battle is often termed as the 'decisive event' which became the source of ultimate rule of British in India. The battle occurred during the reign late reign of Mughal empire (called later Mughal Period). Mughal emperor Alamgir-II was ruling the empire when the Battle of Plassey took place. A few historians, while answering the question as to when did the British rule start in India, cite the Battle of Plassey as the source. This article will talk about the Battle of Plassey in detail to help IAS Exam aspirants understand it for both prelims and mains (GS-I). You can also download the Battle of Plassey notes PDF from the link provided. Table of Contents: What is the Battle of Plassey? Causes of the Battle of Plassey Who Fought the Battle of Plassey? Effects of Battle of Plassey What is the Battle of Plassey? It is a battle fought between the East India Company force headed by Robert Clive and Siraj-Ud-Daulah (Nawab of Bengal). The rampant misuse by EIC officials of trade privileges infuriated Siraj. The continuing misconduct by the EIC against Siraj-Ud-Daulah led to the battle of Plassey in 1757.