From Civic Education to a Civic Learning Ecosystem: a Landscape Analysis and Case for Collaboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Status and Competitiveness of K-Pop Korean Wave on the Southeast Asia

Current status and competitiveness of K-pop Korean Wave on the Southeast Asia Quoc Trung Pham1, Jong Won Yun2 1 HCMC University of Technology (VNU-HCM), Vietnam 2 Changwon National University, Korea 2020 K-WCEB International Symposium (“Building Business Relationships between World Chinese Entrepreneurs and Korea”) 13-14/11/2020 - Online Conference - Changwon National University Studio Contents 1. Introduction 2. Current status of K-pop on the Southeast Asia 3. Competitiveness of Korean wave in Vietnam 4. Future trends & Suggestion 5. Conclusion 1. Introduction In digital society, entertainment and creative industry becomes one of the most important sectors of any country. Since 2000s, the Korean Wave or K-pop evolved into a global phenomenon, carried by the Internet and entertainment technologies. The Korean wave has spread the influence of aspects of Korean culture including fashion, music, TV programs, cosmetics, games, cuisine, web-toon and beauty. K-pop or Korean wave could be used as a strategy of Korea to improve its national brand and to support cultural products exportation. Some challenges for K-pop development in the future include: The competition with J-pop, Western music and other cultural trends The impact of Covid-19 pandemic A change in policy of South Korea Government toward the Indochina Peninsula A need to review the current status and the competitiveness of K-pop in the Southeast Asia region A suitable policy to raise the impact of Korean wave in this region and to support the further development of Korean and regional economy. 2. Current status of K-pop on the ASEAN (1) Top 5 countries spending most time for K-pop idols in 2020 include: 1/ Indonesia, 2/ Thailand, 3/ Vietnam, 4/ Malaysia, 5/ Brazil (Yan.vn, 2020) Singapore There is a thriving K-pop fan-base in Singapore, where idol groups, such as 2NE1, BTS, Girls' Generation, Got7 and Exo, often hold concert tour dates. -

Teaser Memorandum

Teaser Memorandum The First Half of 2017 Investment Opportunities In Korea Table of Contents Important Notice ………………………………… 1 Key Summary ………………………………… 2 Expected Method of Investment Promotion …………………………… 3 Business Plan ………………………………… 4 Business Introduct ………………………………… 5 License ………………………………… 11 Capacity ………………………………… 12 Market ………………………………… 13 Financial Figures ………………………………… 14 Key Summary Private & Confidential Investment Highlights RBW is a K-POP (Hallyu) contents production company founded by producer/songwriter Kim Do Hoon, Kim Jin Woo, and Hwang Sung Jin, who have produced numerous K-POP artists such as CNBLUE, Whee-sung, Park Shin Hye, GEEKS, 4MINUTE etc. Based on the “RBW Artist Incubating System’, the company researches and provides various K-POP related products such as OEM Artist & Music Production (Domestic/Overseas), Exclusive Artist Production (MAMAMOO, Basick, Yangpa etc.), Overseas Broadcasting Program Planning & Production (New concept music game show/Format name: RE:BIRTH), and K-POP Educational Training Program. With its business ability, RBW is currently making a collaboration with various domestic and overseas companies, including POSCO, NHN, Human Resources Development Service of Korea, Ministry of Labor & Employment, and KOTRA. • Business with RBW’s Unique Artist Incubating •Affiliation Relationship with International Key Factors System Companies Description • With analyzing the artists’ potentials and market trend, every stage for training and debuting artists (casting, training, producing, and album production) is efficiently processed under this system. Pictures Company Profiles Category Description Establishment Date 2013. 8. 26 Revenue 12 Billion Won (12 Million $) (2016) Website www.rbbridge.com Current Shareholder C.E.O. Kim Jin Woo 29.2%, C.E.O. Kim Do Hoon 29.2%, Institutional Investment 31.7%, Executives and Staff Composition 5.6%, Etc. -

The New Hampshire, Vol. 75, No. 19

The New Hampshire Vol. 75 l\ o . 19 FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 1984 Bui ~ Ra tl' 1 · .S . P ostapc· l'a id Durham , . 11 . l'L' I 111i 1 /1 30 Graffiti shows war hazards By Patricia O'Dell ing Hall, Zais Hall, Kingsbury Wednesday students no Hall, Parsons Hall, and Conant ticed white spray painted out-_ Hall. lines of human figures on side According to one bystander, walks on campus. "it's good we're expressing the Responsibility for them is need for nuclear disarmament. claimed by two groups. One is As long as vandalism leads to called People Against Nuclear a good end, which nuclear Vaporization and the other, The disarmament is, its all right." November 6th Coalition. A But according to student Scott _representative of the November Lincoln, such vandalism is "the 6th Coalition said he and the worst thing I've seen all semes · other members of the group ter. It's embarrassing and fr 's were inspired by the victory of disgus_ting. One group does it President Ronald Reagan in and gets away with it and Tuesday's election. everyone else does it too." "People must realize we are The figures are a strange way closer now to the possible use to get a message across, accord of nuclear weapons." ing to Pat Miller, Executive The group is made up of both Director of Facilities Services. students and non-students who He questioned whether stu One of the many painted figures that appeared aroung the UNH campus sometime Wednesday are "concerned people," he said~- dents will understand what the . -

K-Pop Performance

Sindicato dos Profissionais de Dança do Estado do Rio de Janeiro Apostila de conteúdo e referências Para a Prova Teórica de K - Performance MATERIAL TEÓRICO PARA PROVA DE OBTENÇÃO DE REGISTRO PROFISSIONAL Modalidade: K-Performance A Dança: A dança e uma forma de comunicação e manifestação de celebrações e acontecimentos cotidianos. De lá pra cá novas formas surgiram, nomenclaturas e estilos diversos, mas nunca esquecendo do seu propósito maior, usar a dança como uma manifestação artística e comunicação do artista através dos movimentos passando sentimentos para os seus espectadores. K-performance: Conceito Podemos considerar K-Performance como qualquer performance de coreografia seja em modalidade cover ou autoral, em músicas de K-pop, com o intuito de entreter e a proposta de coreografia de artista, com Lipsync, expressão corporal condizente com a música e domínio de palco. História K-POP : A História do K-POP começa com o Sr. Lee Soo Man, CEO da SM entertainment, que ao voltar de uma viagem aos Estados Unidos, em 1989, vê uma diferença de como os artistas conseguem ser globalmente conhecidos e os artistas coreanos não conseguiam ser lanca̧ dos mundialmente. O primeiro cantor lanca̧ do de sua marca foi Hyun Jin-young, e seria o primeiro cantor de algo que se aproximava do que seria o K-pop, dois anos depois teriá mos um divisor de aǵ uas com SeoTaiji. Primeiro Grupo: Seo Taiji and Boys – considerado um dos pioneiros, e por muitos o primeiro grupo de k-pop, esse grupo Debutou em 1992 e, apesar de ficar em atividade apenas de 1992 a 1996, teve vendas entre 1.6 e 2 milhões de cópias pôr álbum. -

Slow and Stored Light Under Conditions of Electromagnetically Induced Transparency and Four Wave Mixing in an Atomic Vapor

SLOW AND STORED LIGHT UNDER CONDITIONS OF ELECTROMAGNETICALLY INDUCED TRANSPARENCY AND FOUR WAVE MIXING IN AN ATOMIC VAPOR Nathaniel Blair Phillips Lancaster, Pennsylvania Master of Science, College of William and Mary, 2006 Bachelor of Arts, Millersville University, Millersville PA, 2004 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Physics The College of William and Mary August 2011 c 2011 Nathaniel Blair Phillips All rights reserved. APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Nathaniel Blair Phillips Approved by the Committee, June, 2011 Committee Chair Assistant Professor Irina Novikova, Physics The College of William and Mary Assistant Professor Seth Aubin, Physics The College of William and Mary Professor John Delos, Physics The College of William and Mary Professor Gina Hoatson, Physics The College of William and Mary Eminent Professor Mark Havey, Physics Old Dominion University ABSTRACT PAGE The recent prospect of efficient, reliable, and secure quantum communication relies on the ability to coherently and reversibly map nonclassical states of light onto long-lived atomic states. A promising technique that accomplishes this em- ploys Electromagnetically Induced Transparency (EIT), in which a strong classical control field modifies the optical properties of a weak signal field in such a way that a previously opaque medium becomes transparent to the signal field. The accom- panying steep dispersion in the index of refraction allows for pulses of light to be decelerated, then stored as an atomic excitation, and later retrieved as a photonic mode. -

Facultad De Ciencias Sociales Y Jurídicas

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y JURÍDICAS GRADO EN COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Título: ESTUDIO DEL IMPACTO DE LA INDUSTRIA MUSICAL SURCOREANA EN OCCIDENTE A TRAVÉS DEL VIDEOCLIP TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO DE INVESTIGACIÓN BIBLIOGRÁFICA 2018/2019 Alumno: Adrián Salguero Vico Tutor: Vicente Javier Pérez Valero 1 ÍNDICE 1. Resumen / abstract …………………………………………………………….. 4 2. Palabras clave / keywords …………………………………………………….. 6 3. Introducción……………………………………………………………………….6 4. Hipótesis………………………………………………………………………….. 7 5. Objetivos…………………………………………………………………………..7 6. Estado de la cuestión y marco teórico…………………………………………8 1. Base y orígenes del fenómeno K-POP………………………………..8 2. Era dorada - Viralización y aparición de YouTube (2009-2015) 1. Videoclip y YouTube…………………………………………….10 2. La 2º generación del K-POP………………………………….. 12 3. Viralización y boom 2012……………………………………... 14 3. Estado actual – nuevos grupos y fórmulas (2015 – actualidad) 1. Expansión del fenómeno fan………………………………….. 17 2. Reconocimiento y expansión…………………………………. 19 3. Marcando la diferencia………………………………………… 20 7. Metodología……………………………………………………………………… 24 8. Resultados……………………………………………………………………….. 25 9. Conclusiones…………………………………………………………………….. 29 10.Bibliografía………………………………………………………………………. 32 11.Anexos 1. Encuesta sobre consumo musical y de K-POP………………………34 2. Resultados de la encuesta…………………………………………….. 51 3. Tabla – análisis videoclips………………………………………………61 2 TABLAS Tabla 1 – Resumen de videoclips visionados…………………………………25 Tabla 2 – Resultados de encuesta……………………………………………..26 GRÁFICOS Gráfico -

STORM Report Is a Compilation of Up-And-Coming Bands and It Has Been a Month Since Membrain Was Artists Who Are Worth Watching

SXSW RECAP G-EAZY Låpsley KSHMR Future Majid Jordan and more THE STORM ISSUE NO. 36 REPORT APRIL 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 EYE OF THE STORM Festival fun. A look at this year's upcoming festivals. 6 STORM TRACKER The latest from our STORM Alumni. 58th Grammy Award nominees 7 STORM FORECAST What to look forward to this month. SXSW, The Grammys, The Oscars Controversy and more. 8 STORM WARNING Our signature countdown of 20 buzzworthy bands and artists on our radar. 19 SOURCES & FOOTNOTES On the Cover Anderson .Paak: Photo by Erik Ian ABOUT A LETTER THE STORM FROM THE REPORT EDITOR STORM = STRATEGIC TRACKING OF RELEVANT MEDIA Hello STORM Readers! The STORM Report is a compilation of up-and-coming bands and It has been a month since memBrain was artists who are worth watching. Only those showing the most in Austin for South by Southwest (SXSW) promising potential for future commercial success make it onto our where our team booked 26 bands for the monthly list. Official Showcases at the McDonald’s Loft venue. A proven hotbed for discovering new How do we know? talent as well as emerging technology, this year’s SXSW also featured surprising brand Through correspondence with industry insiders and our own ravenous activations that seemed to shift audience media consumption, we spend our month gathering names of artists conversations from the “brand invasion” who are “bubbling under”. We then extensively vet this information, to the “brand experience.” In addition to analyzing an artist’s print & digital media coverage, social media McDonald’s (who also featured the most growth, sales chart statistics, and various other checks and balances to buzzed about VR experience of the festival ensure that our list represents the cream of the crop. -

Defining Détente: NATO's Struggle for Identity, 1967-1984

Defining Détente: NATO’s Struggle for Identity, 1967-1984 by Susan Colbourn A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Susan Elizabeth Colbourn 2018 Defining Détente: NATO’s Struggle for Identity, 1967-1984 Susan Elizabeth Colbourn Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2018 Abstract The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) defined détente as one of its central tasks with the Harmel Report of December 1967, alongside the Alliance’s traditional mission of defending the West. After a series of historic improvements in the early 1970s, however, détente’s fortunes faded. East-West relations deteriorated over the second half of the 1970s and into the 1980s, leading many to dub the period a “Second Cold War.” What, then, did this mean for the Atlantic Alliance and the double philosophy of détente and defense staked out in the Harmel Report? Defining Détente: NATO’s Struggle for Identity, 1967-1984 explores détente’s contested nature and its various meanings for policy-makers and publics in the United States, Canada, and across Western Europe. Détente was an ongoing source of tension in transatlantic relations, but neither allied disagreements nor the marked deterioration of East-West relations changed the Alliance’s overall strategy. Détente and defense remained vital to NATO’s posture for the remainder of the Cold War and well into the post–Cold War era. !ii Acknowledgments This dissertation, like so many, would not have been possible without the support of others. Many thanks to my dissertation committee: to Robert Bothwell, whose faith in me and what this project could become was unflagging; to Lynne Viola, who always encouraged me to take my ideas in new directions and to just keep writing; and, to Timothy Sayle, who listened to my ramblings and generously shared documents and ideas from his own work. -

TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO Universidad De Sevilla

TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO Universidad de Sevilla ANÁLISIS DE LA IDENTIDAD VISUAL DEL GRUPO COREANO MAMAMOO (2014-2018) Alumno: María Isabel Fernández Carmona Tutor: Antonio Gómez Aguilar Curso Académico 2017-2018 Convocatoria de Septiembre Facultad de Comunicación Grado en Comunicación Audiovisual ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN…………………………………………………………………………....3 1. Justificación…………………………………………………………………………....3 2. Objetivos…………………………………………………………………………….... 4 3. Metodología…………………………………………………………………………....4 PARTE 1: IDENTIDAD VISUAL…………………………………………………………..6 1. Definición e historia…………………………………………………………………... 6 2. Elementos……………………………………………………………………………... 7 3. Identidad visual de un grupo musical………………………………………………….9 PARTE 2: KPOP…………………………………………………………………………....11 1. Definición e historia…………………………………………………………………. 11 2. Occidente……………………………………………………………………………..13 3. Oriente: el caso coreano……………………………………………………………... 15 3.1. Trainee………………………………………………………………………….16 3.2. Promoción……………………………………………………………………... 16 3.3. Idol……………………………………………………………………………...17 3.4. Concepto………………………………………………………………………..18 3.5. Lines………………………………………………………………………….... 18 3.6. Listas musicales………………………………………………………………...19 3.7. Programas de televisión………………………………………………………...19 3.8. Agencias de entretenimiento…………………………………………………... 21 3.8.1. Rainbow Bridge World………………………………………………....23 PARTE 3. MAMAMOO……………………………………………………………………..25 CONCLUSIÓN……………………………………………………………………………...71 BIBLIOGRAFÍA…………………………………………………………………………....73 -

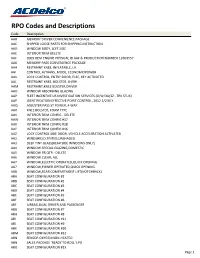

RPO Codes and Descriptions

RPO Codes and Descriptions Code Description AAB MEMORY DRIVER CONVENIENCE PACKAGE AAC SHIPPED LOOSE PARTS FOR SHIPPING INSTRUCTION AAD WINDOW BODY, LEFT SIDE AAE INTERIOR TRIM DELETE AAF 2009 OEM ENGINE PHYSICAL ID AAF & PRODUCTION NUMBER 12603557 AAG MEMORY PASS CONVENIENCE PACKAGE AAH RESTRAINT KNEE, INFLATABLE, LH AAI CONTROL A/TRANS, MODE, ECONOMY/POWER AAK LOCK CONTROL, ENTRY DOOR, ELEC, KEY ACTIVATED AAL RESTRAINT KNEE, BOLSTER, LH/RH AAM RESTRAINT,KNEE BOLSTER,DRIVER AAO WINDOW ABSORBING GLAZING AAP FLEET INCENTIVE US INVESTIGATION SERVICES (D/W/3A/3Z - TRK STUX) AAP IDENTIFICATION EFFECTIVE POINT CONTROL, 2012 1/2 M.Y. AAQ ADJUSTER PASS ST POWER, 4 WAY AAR KNEE BOLSTER, FOAM TYPE AAV INTERIOR TRIM CONFIG - DELETE AAW INTERIOR TRIM CONFIG #17 AAX INTERIOR TRIM CONFIG #18 AAY INTERIOR TRIM CONFIG #16 AAZ LOCK CONTROL SIDE DOOR, VEHICLE ACCELERATION ACTIVATED AA2 WINDSHIELD,TINTED,UNSHADED AA3 DEEP TINT GLASS(REAR SIDE WINDOWS ONLY) AA4 WINDOW SPECIAL GLAZING,DOMESTIC AA5 WINDOW RR QTR - DELETE AA6 WINDOW CLEAR, ALL AA7 WINDOW,ELECTRIC OPERATED,QUICK OPENING AA7 WINDOW,POWER OPERATED,QUICK OPENING AA8 WINDOW,REAR COMPARTMENT LIFT(NOTCHBACK) ABA SEAT CONFIGURATION #1 ABB SEAT CONFIGURATION #2 ABC SEAT CONFIGURATION #3 ABD SEAT CONFIGURATION #4 ABE SEAT CONFIGURATION #5 ABF SEAT CONFIGURATION #6 ABF AIRBAG,DUAL DRIVER AND PASSENGER ABG SEAT CONFIGURATION #7 ABH SEAT CONFIGURATION #8 ABI SEAT CONFIGURATION #11 ABJ SEAT CONFIGURATION #9 ABK SEAT CONFIGURATION #10 ABM SEAT CONFIGURATION #12 ABN SENSOR OXYGEN NON-HEATED ABN SALES PACKAGE -

“The Globalization of Pop Music in 2019: an Analysis of the Anglo-American, Spanish, and South Korean Music Markets.”

“The globalization of pop music in 2019: An analysis of the Anglo-American, Spanish, and South Korean music markets.” Student Name: George Poulitsidis Student Number: 512897 Supervisor: Dr. Marc Verboord Media & Creative Industries Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam Master Thesis June 25th, 2020 ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is twofold. First, is to expand on the current literature by examining the implications that streaming services have brought in the globalization of pop music. Second, is to examine the applicability of the explanatory determinants in this growing digital market, as it is believed that technological advancements could potentially diminish the importance of certain explanatory determinants, such as cultural centrality, cultural proximity, and physical distance. Since streaming consumption accounts for more than half of the overall music consumption worldwide, this is done by analyzing the annual top 100 pop music charts that incorporate both online and offline consumption for the markets of the U.S., the U.K., Spain and South Korea for 2019. Notably, during the analysis further attention is given to the prominence of language and record labels. Overall, the results show that there are substantial differences between the Western markets and the market of South Korea. Generally, South Korea was had most domestically oriented chart in the sample, while U.S. was the most successful origin country. Surprisingly, the international success of K-pop seems to be limited, while Latin music songs and artists were found in all four countries. Furthermore, while the analysis shows that the explanatory determinants, and especially the destination effects, have become less important, the charts still seem to reflect the pre- existing offline power relationships of the industry. -

In the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware

IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE -------------------------------------------------------------- x In re : Chapter 15 : CINRAM INTERNATIONAL INC., et al.,1 : Case No. 12-11882 (KJC) : Debtors in a Foreign Proceeding. : Jointly Administered : -------------------------------------------------------------- x NOTICE OF SECOND AMENDED LIST PURSUANT TO RULE 1007(A)(4) OF THE FEDERAL RULES OF BANKRUPTCY PROCEDURE 1 The last four digits of the United States Tax Identification Number or Canadian Business Number, as applicable, of each of the Debtors follow in parentheses: (a) Cinram International Inc. (4583); (b) Cinram (U.S.) Holding’s Inc. (4792); (c) Cinram, Inc. (7621); (d) Cinram Distribution LLC (3854); (e) Cinram Manufacturing LLC (2945); (f) Cinram Retail Services LLC (1741); (g) Cinram Wireless LLC (5915); (h) IHC Corporation (4225); and (i) One K Studios, LLC (2132). The Debtors’ executive headquarters is located at 2255 Markham Road, Toronto, Ontario, M1B 2W3, Canada. NYDOCS03/951456.1 Dated: Wilmington, Delaware Respectfully submitted, July 3, 2012 SHEARMAN & STERLING LLP Douglas P. Bartner Jill Frizzley Robert Britton 599 Lexington Avenue New York, New York 10022 Telephone: (212) 848-4000 Facsimile: (646) 848-8174 -and- YOUNG CONAWAY STARGATT & TAYLOR, LLP /S/ Kenneth J. Enos Pauline K. Morgan (No. 3650) Kenneth J. Enos (No. 4544) Rodney Square 1000 North King Street Wilmington, DE 19801 Telephone: (302) 571-6600 Facsimile: (302) 571-1253 Co-Counsel to the Foreign Representative NYDOCS03/951456.1 2 APPENDIX 1 Entities Against Whom Provisional Relief is Sought NYDOCS03/951456.1 Appendix 1 - Entities Against which Provisional Relief is Sought Name ADDRESS_LINE1 ADDRESS_LINE2 ADDRESS_LINE3 CITY STATE ZIP Country 1099 PRO,INC 23901 CALABASAS ROAD SUITE #2080 CALABASAS CA 91302-4104 USA 1508235 ONTARIO INC.