Northumbria Research Link

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northumbria University Campus

BINUS Northumbria (Double degree) 3 + 1 Program History Northumbria originally known as Newcastle Polytechnic, the University was formed in 1969 from the amalgamation of three regional colleges: Rutherford College of Technology, the College of Art & Industrial Design, and the Municipal College of Commerce. These colleges themselves had origins which were deeply rooted in the region. Northumbria University Campus It has two separate campuses ; 1. Newcastle City Campus 2. Coach Lane Campus “Both located within Newcastle upon Tyne” Two hours and forty minutes away from London By the fastest rail services. One hour away from Edinburgh (Scotland’s Capital) Newcastle has its own International Airport and whilst regular Ferry Services operate to and from Northern Europe. Newcastle City Campus The City Campus is in the heart of Newcastle upon Tyne, just a couple of roads from the main shopping areas and cultural centres. The campus marries a unique combination of innovative contemporary buildings with historical sites that have been listed because of their heritage and grandeur. Coach Lane Campus The campus is home to all students from the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences. Our state-of- the-art Clinical Skills Centre is a purpose-built facility that will allow you to develop practical skills and gain valuable experience of real hospital situations through a simulated environment. Around Campus Text or Image(s) Area Gateshead Millennium Bridge The Castle Keep & City Walls Jesmond Dene Park Newcastle Upon Tyne Road Newcastle has its own international airport operating both domestic and international flights to cities including London, Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Aberdeen, Dublin, Belfast, Southampton, Amsterdam, Paris, Barcelona, Prague, Dubai and Copenhagen. -

Northumbria University Northumbria University CASE STUDY

Northumbria University STUDY CASE Northumbria University has two a million visitors each year and large city-based campuses in renowned for its buzzing nightlife. Newcastle and uses SafeZone Given the university’s city-centre locations, alerts are typically from as part of its integrated users worried about suspicious approach to help promote people or feeling threatened. and assure student and staff SafeZone enables the Northumbria safety within this busy urban security team to intervene more SafeZoneApp.com environment. quickly, to offer support, and to prevent incidents from escalating. “SafeZone allows us to SafeZone has also helped save lives Northumbria University is home to respond more quickly and by accelerating first-aid support to almost 32,000 students and staff and victims suffering from cardiac arrest, in many cases to prevent was the first university in Europe to stroke, severe choking or an extreme incidents from escalating. adopt SafeZone®. The service is now allergic reaction. used across all its Newcastle facilities, Northumbria’s commitment central London campus and a new to safety and security is recently announced Amsterdam site. also helping us to recruit SafeZone is an essential element in more overseas students Northumbria’s integrated approach to security that includes the university who are increasingly having its own dedicated crime being drawn towards prevention team and full-time Newcastle and our city- police officer. based campuses,” Newcastle is one of the UK’s liveliest JOHN ANDERSON cities, attracting over a quarter of Head of Security at Northumbria University, Newcastle SafeZone solution Benefits and outcomes Northumbria University has an active in their profile. -

LATE HOLOCENE PALAEOSEISMICITY in SOUTH-CENTRAL CHILE Findings So Far OBJECTIVES Research Has Focused Upon the 2010 and 1960 Rupture Zones

Reconstructing Chile’s earthquake history GARRETT DRS EMMA HOCKING & ED Drs Emma Hocking and Ed Garrett outline their efforts to reconstruct land- and sea-level changes in light of the multiple earthquake cycles that have occurred in south-central Chile along the Cascadia and Alaska- Universidad Católica de Valparaíso has been Aleutian subduction zones, influential in getting the research off the particularly in developing ground and his input continues to guide our the idea of the earthquake approach in the field. Our past field seasons in deformation cycle and Chile have been undertaken in collaboration pinpointing criteria for with Dr Rob Wesson of the USGS, Dr Lisa Ely identifying earthquakes in tidal of Central Washington University, Dr Daniel marsh sediments. Melnick of the University of Potsdam and Tina Dura of the University of Pennsylvania, among Can you give a brief overview of others, whose expertise have proved invaluable. your field studies in Chile that began in 2010? How are these What overarching impact do you expect from Could you offer an insight into your investigations informing your current work? this project? What will be next for you and backgrounds? How did your experiences your collaborators? prepare you to lead this current project? In the immediate aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Maule, Chile, we were part Understanding the past earthquake history EG: We both completed PhDs at Durham of a Durham University team making field of an area is key to future preparedness and University, Hocking investigating relative sea observations. The subsequent data have been hazard mitigation. Our research aims to level change in Antarctica and me studying critical in helping us understand the immediate help understand more about how frequently megathrust earthquakes in Chile. -

GGA 2017 Finalists' Flyer

Finalists 113 finalists 15 categories - Team entrepreneurship – Students building Best Newcomer Continuous Improvement: sustainable businesses • # Borders College - Flushed with success! A UK • first in sustainable energy from waste water Institutional Change University of Worcester - Green now Category Supporter: Scottish Funding white bags: Five years skilling students – a • MidKent College - We can see the wood from University/City recycling collaboration the trees! Council • Northumbria University - Improving • Aston University - Embedding sustainability at sustainability together – our success story (so Aston University Facilities and Services far…) • Canterbury Christ Church University - • Loughborough University - Maintaining the • Southampton Solent University - Building a sustainable future: From start to green. Living the sporting dream Environmental and sustainability strategy – beginning • Middlesex University - MDX freewheelers Waste improvement project • Goldsmiths, University of London - • Middlesex University - MDX goes green Continually greening Goldsmiths • Sheffield Hallam University - Closing the Carbon Reduction • London Metropolitan University - Going above waste loop Category Supporter: The Energy Consortium and beyond! • Sheffield Hallam University - Driving towards • - Zero by 2040 – The a sustainable fleet • Goldsmiths, University of London - The University of Edinburgh Energy Detectives – investigating and solving University of Edinburgh’s climate strategy • Sheffield Hallam University - Greening our energy waste -

School of Architecture and the Built Environment (SABE)

A Research Strategy 1. Key targets and objectives in RAE 2001 1.1 Key events and outcomes This Unit of Assessment (UoA) covers Transport and Logistics; Housing, Planning and Regeneration; and Tourism, for which the relevant research groups are based in the School of Architecture and the Built Environment (SABE). In addition, SABE is making a submission to UoA 30 (Architecture and the Built Environment) for the first time. During the period 2001-07, those submitting to UoA 31 have secured research funding in excess of £5.3m, published at least 75 refereed journal articles, 10 chapters and eight books, as well as producing many research reports for clients (see www.wmin.ac.uk/sabe/page-5 and www.wmin.ac.uk/westminsterresearch for the institutional repository for staff publications). The range and quality of our research has been reinforced by the internal appointment of three professors (Bailey, Roberts and Newman), one Reader (Maitland) and three post-doctoral fellowships (Kamvasinou is entered in RA2) since 2001. New Lecturer and Researcher appointments are fully integrated in the School’s vibrant research culture. All the research groups discussed below have enhanced their international reputation through the recruitment of researchers and research students, as well as by securing research commissions against substantial competition. Research clusters are extending their contacts with national and international research networks and institutional contacts overseas. As well as the research outputs discussed here and in RA2, the research clusters carry out a wide range of applied research for public, private and charitable clients in the wider built environment ‘policy community’. -

14 Could Be Peak Age for Believing in Conspiracy Theories

A study conducted by a team of psychologists has uncovered that belief in conspiracy theories flourishes in teenage years. Feb 09, 2021 08:04 GMT 14 COULD BE PEAK AGE FOR BELIEVING IN CONSPIRACY THEORIES Belief in conspiracy theories is heightened as adolescents reach 14 years of age, reveals new research led by Northumbria University. A study conducted by a team of psychologists from across the UK has uncovered that belief in conspiracy theories flourishes in teenage years. More specifically, they found that 14 is the age adolescents are most likely to start believing in conspiracy theories, with beliefs remaining constant into early adulthood. The findings were discovered using the first ever scientific measure of conspiracy beliefs suitable for analysing younger populations. A paper detailing the research has been published in the British Journal of Developmental Psychology online today. Addressing gaps in research Previous research has demonstrated that conspiracy theories can affect people’s beliefs and behaviours in significant ways. For example, they can influence people’s views and decisions on important issues such as climate change and vaccinations. With around 60% of British people believing in at least one conspiracy theory, understanding their popularity is important. Despite their significance, however, all existing research on conspiracy theories has been conducted with adults, and research methods used to measure conspiracy beliefs have been designed only with adults in mind. To date, therefore, there has been a lack of knowledge about when and why conspiracy beliefs develop in young people, and how these beliefs change over time. Now, a timely project funded by the British Academy has developed and validated a conspiracy beliefs questionnaire suitable for young people, called the Adolescent Conspiracy Beliefs Questionnaire (ACBQ). -

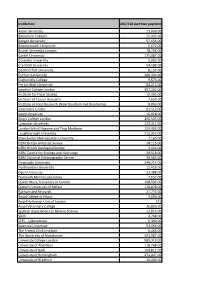

2017-18 Block Grant Awards – Part Two Payments

Institution 2017/18 part two payment Aston University 11,000.00 Babraham Institute 15,095.00 Bangor University 57,656.00 Bournemouth University 5,672.00 Brunel University London 78,766.00 Cardiff University 175,087.00 Coventry University 9,083.00 Cranfield University 54,588.00 De Montfort University 8,137.00 Durham University 200,334.00 Goldsmiths College 9,573.00 Heriot-Watt University 84,213.00 Imperial College London 357,202.00 Institute for Fiscal Studies 10,303.00 Institute of Cancer Research 7,620.00 Institute of Food Research (Now Quadram Inst Bioscience) 8,853.00 John Innes Centre 63,512.00 Keele University 16,918.00 King's College London 296,503.00 Lancaster University 123,311.00 London Sch of Hygiene and Trop Medicine 153,402.00 Loughborough University 212,352.00 Manchester Metropolitan University 7,165.00 NERC British Antarctic Survey 28,115.00 NERC British Geological Survey 3,424.00 NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology 24,518.00 NERC National Oceanography Centre 26,992.00 Newcastle University 248,714.00 Northumbria University 12,456.00 Open University 31,388.00 Plymouth Marine Laboratory 7,657.00 Queen Mary, University of London 198,434.00 Queen's University of Belfast 110,878.00 Rothamsted Research 27,772.00 Royal College of Music 3,690.00 Royal Holloway, Univ of London 215 Royal Veterinary College 26,890.00 Scottish Association For Marine Science 12,814.00 SRUC 4,768.00 STFC - Laboratories 5,390.00 Swansea University 51,494.00 The Francis Crick Institute 6,466.00 The University of Manchester 591,987.00 University College -

Northumbria Research Link

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Liyanage, Lalith (2013) A case study of the effectiveness of the delivery of work based learning from the perspective of stakeholders in Computing, Engineering and Information Sciences at Northumbria University. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/21418/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html A CASE STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE DELIVERY OF WORK BASED LEARNING FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF STAKEHOLDERS IN COMPUTING, ENGINEERING AND INFORMATION SCIENCES AT NORTHUMBRIA UNIVERSITY LALITH LIYANAGE PhD 2013 1 A CASE STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE DELIVERY OF WORK BASED LEARNING FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF STAKEHOLDERS IN COMPUTING, ENGINEERING AND INFORMATION SCIENCES AT NORTHUMBRIA UNIVERSITY LALITH LIYANAGE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in Faculty of Engineering and Environment April 2013 2 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. -

MA/Msc/PG Dip Information and Library Management (DL) Msc/PG Dip Information and Records Management (DL)

Faculty of Engineering and Environment MA/MSc/PG Dip Information and Library Management (DL) MSc/PG Dip Information and Records Management (DL) Programme Handbook 2015 - 2016 Contents 1 Welcome from the Programme Leaders ......................................................................... 3 2 About this handbook ...................................................................................................... 5 3 Who’s Who and Communication .................................................................................... 5 3.1 Who to go to for help ............................................................................................... 5 Programme Administrator – Distance Learning .............................................................. 5 Student Support Team ................................................................................................... 6 Programme Leaders: Julie McLeod and Jackie Urwin .................................................... 6 Module Tutors ................................................................................................................ 7 3.2 Communication ....................................................................................................... 7 Contacting Your Programme Leader and Module Tutors ............................................... 7 Email .............................................................................................................................. 7 eLearning Portal............................................................................................................ -

Teaching Academics to Teach: About Pedagogy

Roberts, Nicola (2013) Teaching Academics to Teach: About Pedagogy. Emerge, 5. pp. 1-16. Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/id/eprint/7407/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. EMERGE 2013: Article Issue 5, pp. 1-16 Teaching Academics to Teach: About Pedagogy Dr. Nicola Ballantyne University of Sunderland Abstract Higher education institutions have become increasingly concerned about retaining students largely because they are penalised financially for losing them. Whilst much has been written about the impact factors such as finances, family support and previous education has upon students’ withdrawal from higher education, much less focus appears to be on actual ‘classroom’ practices. Student-centred approaches to teaching and learning produce ‘higher quality learning outcomes’ in students and thereby facilitate students’ retention at university. For these reasons, this research sought to assess pedagogical practices at a University in the North of England. Six first-year tutors were interviewed and their teaching observed. Findings indicate that whilst tutors recognised the challenges their students faced in learning and staying-power at university, and despite some pockets of exemplary teaching practices, most tutors lacked ‘proper pedagogical knowledge’ about teaching and learning in higher education. The research has implications for university infrastructures, namely teacher- training and creative teaching strategies. Pedagogy and the Retention of Students Universities are penalised financially if they struggle to retain recruited students (Crosling, Thomas and Heagney, 2008). First-year students are particularly vulnerable to dropping-out of university (Yorke, 2000; McInnis, 2001; Haggis and Pouget, 2002; Christie, Munro and Fisher, 2004; Baderin, 2005; Wilcox, Winn and Fyvie-Gauld, 2005). -

Student, Applicant and Enquirer Privacy Notice September 2019

Student, Applicant and Enquirer Privacy Notice 1. Data Controller University of Northumbria at Newcastle (“we”, “our”, “us”) is registered as a Data Controller (Registration Number: Z7674926) with the Information Commissioner’s Office for the purpose of processing personal data. We are committed to processing personal data in accordance with our obligations under the (GDPR) and related UK data protection legislation. 2. Overview This privacy notice describes how and why we process personal data in relation to any individual (“you”, “your”) submitting enquiries and/or applications to the University or when enrolling on any programme of study at any of our locations, including collaborative or foundation programmes, undergraduate or postgraduate (taught or research) programmes offered by us, or our partners, pathway students, degree apprentices, distance learning and CPD (Short Courses). 3. Where do we get your personal data from? We may obtain personal data direct from you when: • Submitting enquiries to us or requesting a prospectus via our website, through social media, by telephone, or emails. • Registering for or attending open days, outreach events, careers fairs and external recruitment events whether in the UK, overseas or online. • You apply to the University and via transactional activities as part of the application process. • It is generated through your interactions with us as part of your studies, your use of University resources, services and systems and any other interactions with the University. From third parties such as: • UCAS, external recruitment representatives, University regional and country offices overseas, collaborative/partner institutions or organisations. • Your current or previous places of study, employer(s) or placement providers. -

University Placements the Following Gives an Overview of the Many Universities Tanglin Graduates Have Attended Or Received Offers from in 2018 and 2019

University Placements The following gives an overview of the many universities Tanglin graduates have attended or received offers from in 2018 and 2019. United Kingdom United States of America Abertay University Amherst College Aston University Arizona State University Student Destinations 2019 Bath Spa University Berklee College of Music Bournemouth University Boston University Central School of St Martin’s, UAL Brown University City, University of London Carleton College 1% Malaysia Coventry University Chapman University 7% De Montfort University Claremont McKenna College National Durham University Colorado State University 1% Italy Service Edinburgh Napier University Columbia College, Chicago Falmouth University Cornell University 1% Singapore Goldsmiths, University of London Duke University 1% Hong Heriot-Watt University Elon University Kong 1% Spain Imperial College London Emerson College King’s College London Fordham University 2% Holland Lancaster University Georgia Institute of Technology Liverpool John Moores University Georgia State University 4% Gap Year 64% UK London School of Economics and Hamilton College Political Science Hult International Business School, 2% Canada London South Bank University San Francisco 6% Australia Loughborough University Indiana University at Bloomington Northumbria University John Hopkins University Norwich University of the Arts Loyola Marymount University 11% USA Nottingham Trent University Michigan State University Oxford Brookes University New York University Queen’s University Belfast Northeastern