Maine State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2003-2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peaks-Kenny State Park Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands 401 State Park Road 106 Hogan Road Dover-Foxcroft, ME 04426 Bangor, ME 04401

The Maine Highlands Region Directions From Dover-Foxcroft, take Route 153 approxi- mately 4.5 miles and turn left on State Park Road. Fees All fees are payable at the Park’s entrance. See online information: • Day Use & Boat Launches: www.maine.gov/doc/parks/programs/DUfees.html • Camping: www.campwithme.com • Annual Individual & Vehicle Passes: www.maine.gov/doc/parks/programs/parkpasses.html Contacts Peaks-Kenny State Park Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands 401 State Park Road 106 Hogan Road Dover-Foxcroft, ME 04426 Bangor, ME 04401 In season: 207-564-2003 Off season: 207-941-4014 Twelve picnic table “sculptures” were created in the park by Artist Wade Kavanaugh Services & Facilities through Maine’s Per Cent for Art act. • 56 private single-party campsites on well-spaced, wooded sites Overview Property History • Day use area with 50 picnic sites (with grills) A peaceful campground with trails • Handicap-accessible picnic site and campsite eaks-Kenny State Park lies on the shores of Sebec Lake, he land that now constitutes the developed portions of offering day visitors and campers a peaceful, wooded Peaks-Kenny State Park was given to the State in 1964 • Sandy swim beach with lifeguard (in summer) and canoe rentals on scenic Sebec Lake setting in which to enjoy boating, fishing, swimming, by a prominent citizen and lawyer in Dover-Foxcroft, • 10 miles of gentle hiking trails P T hiking and picnicking. With 56 sites set among stately trees and Francis J. Peaks, who served in the Maine House of Representa- • Playground area with equipment large glacial boulders near the lake, the campground fosters tives. -

The Maine Chance

The claim of a federal “land grab” in response to the creation of Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument in Maine revealed a lack of historical awareness by critics of how two other cherished parks were established there: through private-public partnerships and the donation of land by private citizens. The maine chance PRIVATE-PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP AND THE KATAHDIN WOODS AND WATERS NATIONAL MONUMENT t is never over until it is…and even then, it might not be. That conundrum-like declaration is actually a straightforward assessment of the enduring, at times I acrimonious, and always tumultuous series of political debates that have enveloped the U.S. public lands—their existence, purpose, and mission—since their formal establishment in the late nineteenth century. From Yellowstone Washington. Congress shall immediately pass universal legislation National Park (1872) and Yellowstone Timberland Reserve (1891) providing for a timely and orderly mechanism requiring the federal to Bears Ears National Monument (2017), their organizing prin- government to convey certain federally controlled public lands to ciples and regulatory presence have been contested.1 states. We call upon all national and state leaders and represen- The 2016 presidential campaign ignited yet another round of tatives to exert their utmost power and influence to urge the transfer this longstanding controversy. That year’s Republican Party plat- of those lands, identified in the review process, to all willing states form was particularly blunt in its desire to strip away federal man- for the benefit of the states and the nation as a whole. The residents agement of the federal public lands and reprioritize whose interests of state and local communities know best how to protect the land the party believed should dominate management decisions on where they work and live. -

Natural Landscapes of Maine a Guide to Natural Communities and Ecosystems

Natural Landscapes of Maine A Guide to Natural Communities and Ecosystems by Susan Gawler and Andrew Cutko Natural Landscapes of Maine A Guide to Natural Communities and Ecosystems by Susan Gawler and Andrew Cutko Copyright © 2010 by the Maine Natural Areas Program, Maine Department of Conservation 93 State House Station, Augusta, Maine 04333-0093 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the authors or the Maine Natural Areas Program, except for inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Illustrations and photographs are used with permission and are copyright by the contributors. Images cannot be reproduced without expressed written consent of the contributor. ISBN 0-615-34739-4 To cite this document: Gawler, S. and A. Cutko. 2010. Natural Landscapes of Maine: A Guide to Natural Communities and Ecosystems. Maine Natural Areas Program, Maine Department of Conservation, Augusta, Maine. Cover photo: Circumneutral Riverside Seep on the St. John River, Maine Printed and bound in Maine using recycled, chlorine-free paper Contents Page Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 3 Foreword ..................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................... -

Senate, Index

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from electronic originals (may include minor formatting differences from printed original) RECORD INDEX – MAINE SENATE 123rd LEGISLATURE - A - ABANDONED PROPERTY Management Law Enforcement Agencies LD 1085 231, 632 ABORTION Providers Mandatory Reporters Of Sex Abuse LD 61 57, 526 Services Funds To Reimburse Eligible Women LD 1309 259, 689 Vital Statistics Published Annually LD 973 225, 604 ABUSE & NEGLECT Children Failure To Ensure School Attendance LD 454 118, 854, 871-872 (RM), 898, 981 Domestic Abuse/Sexual Assault Programs Funds LD 2289 1747-1756 (RM RC) (2), 1756 (RC) Domestic Violence Shelters Addresses Confidential LD 2271 1670, 1720, 1779 Training Criminal Justice Academy LD 1039 225, 938, 976, 1066 Victims Review Of Measures To Protect LD 1990 1323, 1730, 1763, 1861 (RM RC) Economic Recovery Loan Program LD 1796 370, 407, 415-420 (RM RC), 422-423 (RM RC) Mandated Reporters Animal Control Officers LD 584 137, 581, 610, 668 Family Violence Victim Advocates LD 2243 1518, 1776, 1810 Sexual Assault Counselor LD 2243 1518, 1776, 1810 Protection From Dating Partner Stalk/Assault Victim LD 988 226, 849, 898, 981 Sexual Assault & Domestic Violence Prevention School & Community-Based LD 1224 234, 1031 Suspicious Child Deaths Investigations & Reporters LD 2000 1324, 1784, 1861 ACCESS TO INFORMATION Adoptees Medical & Family History LD -

100 Things to Do in the Greater Bangor Region!

100 Things to Do in the Greater Bangor Region! 1. Take a cruise on the Katahdin Steamship on Moosehead Lake. 2. Meet Abraham Lincoln’s Vice President, Hannibal Hamlin on the Kenduskeag Promenade, between Central and State Streets. 3. Walk the boardwalk through a National Natural Landmark at the Orono Bog Walk. 4. Hike hundreds of miles of natural trails at the Bangor City Forest. 5. Drive up Thomas Hill to visit the 50-foot high and 75-foot diameter steel tank, which holds 1.75 million gallons of water, called the Thomas Hill Standpipe. 6. Admire the lighted water fountain and a waterfall that's more than 20 feet high at Cascade Park. 7. Tour through the rotating exhibition galleries at the UMaine Art Museum. 8. Fish for small mouth bass, land-locked salmon, or wild brook trout on Moosehead Lake. 9. Play 27 holes of golf in the middle of the city at the Bangor Municipal Golf Course. 10. Browse through thousands upon thousands of books at the Bangor Public Library. 11. Check out an old River City Cinema movie at a local church or outside venue during the summer. 12. Grab your binoculars and watch the abundant bird life at the Jeremiah Colburn Natural Area. 13. Escape the city heat take a ride down the waterslides at the Beth Pancoe Municipal Aquatic Center. 14. Leisurely walk along the Penobscot River at Bangor’s Waterfront Park and enjoy the sunset. 15. Savor the deliciousness of different kinds of local wines at the Winterport Winery. 16. Pet a lamb or milk a cow at many of Maine’s farms while learning how they operate, meeting animals, and tasting their farm fresh products on Open Farm Day. -

Maine SCORP 2009-2014 Contents

Maine State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2009-2014 December, 2009 Maine Department of Conservation Bureau of Parks and Lands (BPL) Steering Committee Will Harris (Chairperson) -Director, Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands John J. Daigle -University of Maine Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Program Elizabeth Hertz -Maine State Planning Office Cindy Hazelton -Maine Recreation and Park Association Regis Tremblay -Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Dan Stewart -Maine Department of Transportation George Lapointe -Maine Department of Marine Resources Phil Savignano -Maine Office of Tourism Mick Rogers - Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands Terms Expired: Scott DelVecchio -Maine State Planning Office Doug Beck -Maine Recreation and Parks Association Planning Team Rex Turner, Outdoor Recreation Planner, BPL Katherine Eickenberg, Chief of Planning, BPL Alan Stearns, Deputy Director, BPL The preparation of this report was financed in part through a planning grant from the US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, under the provisions of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965. Maine SCORP 2009-2014 Contents CONTENTS Page Executive Summary Ex. Summary-1 Forward i Introduction Land and Water Conservation Fund Program (LWCF) & ii Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) ii State Requirements iii Planning Process iii SCORP’s Relationship with Other Recreation and Conservation Funds iii Chapter I: Developments and Accomplishments Introduction I-1 “Funding for Acquisition” I-1 “The ATV Issue” I-1 “Maintenance of Facilities” I-2 “Statewide Planning” I-4 “Wilderness Recreation Opportunities” I-5 “Community Recreation and Smart Growth” I-7 “Other Notable Developments” I-8 Chapter II: Major Trends and Issues Affecting Outdoor Recreation in Maine A. -

Baxter State Park Annual Operating Report for the Year 2015 to the Baxter State Park Authority October 2016

Baxter State Park Annual Operating Report For the Year 2015 To the Baxter State Park Authority October 2016 1 2 Contents 1 Director’s Summary .................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Baxter State Park Authority 7 1.2 Park Committees 7 1.3 Friends of Baxter State Park 8 1.3.1 Trail Support ............................................................................................................................. 8 1.3.2 Volunteer Coordinator ............................................................................................................. 8 1.3.3 Outreach & Education .............................................................................................................. 8 1.3.4 Maine Youth Wilderness Leadership Program ........................................................................ 8 1.3.5 Plants of Baxter State Park Project .......................................................................................... 9 1.3.6 Advocacy .................................................................................................................................. 9 1.3.7 Baxter Park Wilderness Fund ................................................................................................... 9 1.3.8 Search & Rescue ....................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Appalachian Trail Issues 9 1.5 Trautman Trail Improvement Initiative 10 1.6 -

Website Burnt Island Lighthouse Restoration 2020.Docx

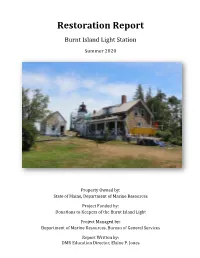

Restoration Report Burnt Island Light Station Summer 2020 Property Owned by: State of Maine, Department of Marine Resources Project Funded by: Donations to Keepers of the Burnt Island Light Project Managed by: Department of Marine Resources, Bureau of General Services Report Written by: DMR Education Director, Elaine P. Jones Abstract On November 9, 1821, Keeper Joshua B. Cushing lit up the Burnt Island Lighthouse for the very first time. After his tenure, 30 other men followed his footsteps up those winding stairs into the lantern-room to illuminate Boothbay Harbor’s guiding light. This monument of hope and integrity has served mariners for nearly 200 years and its devoted keepers served it in return. However, in 1988 automation took away the last true lighthouse keeper, thus removing the love, attention, and financial backing that went into maintaining a lighthouse, keeper’s dwelling, and outbuildings. Built the year after Maine became a state, the lighthouse’s rubble-stone construction has never been altered making it Maine’s oldest “original” lighthouse. From afar and with a fresh coat of paint each year, the iconic beacon looked pretty good, but under a thick layer of stucco it was a different story. Not only had its 199-year-old mortar crumbled; its lantern-room and spiral stairs had rusted; its interior brick liner needed repairs; and surfaces inside and out needed paint. With its 200th Anniversary just one year away, there was no better time than now to restore the entire Burnt Island Light Station. It was high time to stop the deterioration and take action to preserve what was left and replace what was in disrepair. -

Scientific Assessment of Hypoxia in U.S. Coastal Waters

Scientific Assessment of Hypoxia in U.S. Coastal Waters 0 Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) 6 0 Depth (m) 80 32 Salinity 34 Interagency Working Group on Harmful Algal Blooms, Hypoxia, and Human Health September 2010 This document should be cited as follows: Committee on Environment and Natural Resources. 2010. Scientific Assessment of Hypoxia in U.S. Coastal Waters. Interagency Working Group on Harmful Algal Blooms, Hypoxia, and Human Health of the Joint Subcommittee on Ocean Science and Technology. Washington, DC. Acknowledgements: Many scientists and managers from Federal and state agencies, universities, and research institutions contributed to the knowledge base upon which this assessment depends. Many thanks to all who contributed to this report, and special thanks to John Wickham and Lynn Dancy of NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science for their editing work. Cover and Sidebar Photos: Background Cover and Sidebar: MODIS satellite image courtesy of the Ocean Biology Processing Group, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Cover inset photos from top: 1) CTD rosette, EPA Gulf Ecology Division; 2) CTD profile taken off the Washington coast, project funded by Bonneville Power Administration and NOAA Fisheries; Joseph Fisher, OSU, was chief scientist on the FV Frosti; data were processed and provided by Cheryl Morgan, OSU); 3) Dead fish, Christopher Deacutis, Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management; 4) Shrimp boat, EPA. Council on Environmental Quality Office of Science and Technology Policy Executive Office of the President Dear Partners and Friends in our Ocean and Coastal Community, We are pleased to transmit to you this report, Scientific Assessment ofHypoxia in u.s. -

110 Stat. 3901

PUBLIC LAW 104-324—OCT. 19, 1996 110 STAT. 3901 Public Law 104-324 104th Congress An Act To authorize appropriations for the United States Coast Guard, and for other Oct. 19, 1996 purposes. [S. 1004] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Coast Guard Authorization SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. Act of 1996. This Act may be cited as the "Coast Guard Authorization Act of 1996". SEC. 2. TABLE OF CONTENTS. The table of contents for this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title. Sec. 2. Table of contents. TITLE I—AUTHORIZATION Sec. 101. Authorization of appropriations. Sec. 102. Authorized levels of military strength and training. Sec. 103. Quarterly reports on drug interdiction. Sec. 104. Sense of the Congress regarding funding for Coast Guard. TITLE II—PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT IMPROVEMENT Sec. 201. Provision of child development services. Sec. 202. Hurricane Andrew relief Sec. 203. Dissemination of results of 0-6 continuation boards. Sec. 204. Exclude certain reserves from end-of-year strength. Sec. 205. Officer retention until retirement eligible. Sec. 206. Recruiting. Sec. 207. Access to National Driver Register information on certain Coast Guard personnel. Sec. 208. Coast Guard housing authorities. Sec. 209. Board for Correction of Military Records deadline. Sec. 210. Repeal temporary promotion of warrant officers. Sec. 211. Appointment of temporary officers. Sec. 212. Information to be provided to officer selection boards. Sec. 213. Rescue diver training for selected Coast Guard personnel. Sec. 214. Special authorities regarding Coast Guard. TITLE III—MARINE SAFETY AND WATERWAY SERVICES MANAGEMENT Sec. -

Maine State Legislature

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from electronic originals (may include minor formatting differences from printed original) STATE OF MAINE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE MATTHEW DUNLAP SECRETARY OF STATE February I, 2016 Mr. Grant Pennoyer, Executive Director Maine State Legislative Council 115 State House Station Augusta, ME 04333-0115 Dear Mr. Pennoyer, Maine Revised Statutes Title 5, §8053-A, sub-§5, provides that by February I ' 1 of each year, the Secretary of State shall provide the Executive Director of the Legislative Council with lists, by agency, of all rules adopted by each agency in the previous calendar year. I am pleased to present the report for 2015. The list must include, for each rule adopted, the following information: A) The statutory authority for the rule and the rule chapter number and title; B) The principal reason or purpose for the rule; C) A written statement explaining the factual and policy basis for each rule; D) Whether the rule was routine technical or major substantive; E) If the rule was adopted as an emergency; and F) The fiscal impact of the rule. In 2015, there were 260 rules adopted by 22 agencies. Following is a list of the agencies with the number of rules adopted: Agency Total Routine Major Emergency Non Rules Technical Substantive Emergency Department of Agriculture, Conservation 39 36 3 12 27 and Forestry Department of Professional -

Sebasco Harbor Resort, Rte

04_595881 ch01.qxd 6/28/06 9:57 PM Page 1 Chapter 1 Taking in the Scenery Awesome Vistas . 2 Seven Beautiful Bridges . 12 Drives . 20 Train Rides . 32 Boat Rides . 41 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Sequoia National Park. 04_595881 ch01.qxd 6/28/06 9:57 PM Page 2 TAKING IN THE SCENERY Awesome Vistas 1 Monument Valley The Iconic Wild West Landscape Ages 6 & up • Kayenta, Arizona, USA WHEN MOST OF US THINK of the American visits backcountry areas that are other- West, this is what clicks into our mental wise off-limits to visitors, including close- Viewmasters: A vast, flat sagebrush plain ups of several natural arches and with huge sandstone spires thrusting to Ancient Puebloan petroglyphs.) the sky like the crabbed fingers of a Sticking to the Valley Drive takes primeval Mother Earth clutching for the you to 11 scenic overlooks, once-in-a- heavens. Ever since movie director John lifetime photo ops with those incredible Ford first started shooting westerns here sandstone buttes for backdrop. Often in the 1930s, this landscape has felt famil- Navajos sell jewelry and other crafts at iar to millions who have never set foot the viewing areas, or even pose on horse- here. We’ve all seen it on the big screen, back to add local color to your snapshots but oh, what a difference to see it in real (a tip will be expected). life. John Wayne—John Ford’s favorite lead- If you possibly can, time your visit to ing cowboy—roamed these scrublands include sunset—as the sheer walls of on horseback, and seeing it from a West- these monoliths capture the light of the ern saddle does seem like the thing to do.