The Ratcatcher Syllogism: Notes for a Philosophy of Private Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schurken Im Batman-Universum Dieser Artikel Beschäftigt Sich Mit Den Gegenspielern Der ComicFigur „Batman“

Schurken im Batman-Universum Dieser Artikel beschäftigt sich mit den Gegenspielern der Comic-Figur ¹Batmanª. Die einzelnen Figuren werden in alphabetischer Reihenfolge vorgestellt. Dieser Artikel konzentriert sich dabei auf die weniger bekannten Charaktere. Die bekannteren Batman-Antagonisten wie z.B. der Joker oder der Riddler, die als Ikonen der Popkultur Verankerung im kollektiven Gedächtnis gefunden haben, werden in jeweils eigenen Artikeln vorgestellt; in diesem Sammelartikel werden sie nur namentlich gelistet, und durch Links wird auf die jeweiligen Einzelartikel verwiesen. 1 Gegner Batmans im Laufe der Jahrzehnte Die Gesamtheit der (wiederkehrenden) Gegenspieler eines Comic-Helden wird im Fachjargon auch als sogenannte ¹Schurken-Galerieª bezeichnet. Batmans Schurkengalerie gilt gemeinhin als die bekannteste Riege von Antagonisten, die das Medium Comic dem Protagonisten einer Reihe entgegengestellt hat. Auffällig ist dabei zunächst die Vielgestaltigkeit von Batmans Gegenspielern. Unter diesen finden sich die berüchtigten ¹geisteskranken Kriminellenª einerseits, die in erster Linie mit der Figur assoziiert werden, darüber hinaus aber auch zahlreiche ¹konventionelleª Widersacher, die sehr realistisch und daher durchaus glaubhaft sind, wie etwa Straûenschläger, Jugendbanden, Drogenschieber oder Mafiosi. Abseits davon gibt es auch eine Reihe äuûerst unwahrscheinlicher Figuren, wie auûerirdische Welteroberer oder extradimensionale Zauberwesen, die mithin aber selten geworden sind. In den frühesten Batman-Geschichten der 1930er und 1940er Jahre bekam es der Held häufig mit verrückten Wissenschaftlern und Gangstern zu tun, die in ihrem Auftreten und Handeln den Flair der Mobster der Prohibitionszeit atmeten. Frühe wiederkehrende Gegenspieler waren Doctor Death, Professor Hugo Strange und der vampiristische Monk. Die Schurken der 1940er Jahre bilden den harten Kern von Batmans Schurkengalerie: die Figuren dieser Zeit waren vor allem durch die Abenteuer von Dick Tracy inspiriert, der es mit grotesk entstellten Bösewichten zu tun hatte. -

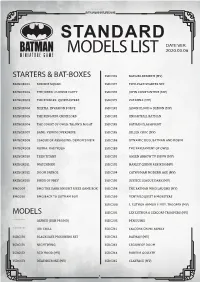

Batman Miniature Game Standard List

BATMANMINIATURE GAME STANDARD DATE VER. MODELS LIST 2020.03.06 35DC176 BATGIRL REBIRTH (MV) STARTERS & BAT-BOXES BATBOX001 SUICIDE SQUAD 35DC177 TWO-FACE STARTER SET BATBOX002 THE JOKER: CLOWNS PARTY 35DC178 JOHN CONSTANTINE (MV) BATBOX003 THE RIDDLER: QUIZMASTERS 35DC179 ZATANNA (MV) BATBOX004 MILITIA: INVASION FORCE 35DC181 JASON BLOOD & DEMON (MV) BATBOX005 THE PENGUIN: CRIMELORD 35DC182 KNIGHTFALL BATMAN BATBOX006 THE COURT OF OWLS: TALON’S NIGHT 35DC183 BATMAN FLASHPOINT BATBOX007 BANE: VENOM OVERDRIVE 35DC185 KILLER CROC (MV) BATBOX008 LEAGUE OF ASSASSINS: DEMON’S HEIR 35DC188 DYNAMIC DUO, BATMAN AND ROBIN BATBOX009 KOBRA: KALI YUGA 35DC189 THE PARLIAMENT OF OWLS BATBOX010 TEEN TITANS 35DC191 GREEN ARROW TV SHOW (MV) BATBOX011 WATCHMEN 35DC192 HARLEY QUINN REBIRTH (MV) BATBOX012 DOOM PATROL 35DC194 CATWOMAN MODERN AGE (MV) BATBOX013 BIRDS OF PREY 35DC195 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK (MV) BMG009 BMG THE DARK KNIGHT RISES GAME BOX 35DC198 THE BATMAN WHO LAUGHS (MV) BMG010 BMG BACK TO GOTHAM BOX 35DC199 VENTRILOQUIST & MOBSTERS 35DC200 L. LUTHOR ARMOR & HVY. TROOPER (MV) MODELS 35DC201 LEX LUTHOR & LEXCORP TROOPERS (MV) ¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨ ALFRED (DKR PROMO) 35DC205 PENGUINS “““““““““ JOE CHILL 35DC211 FALCONE CRIME FAMILY 35DC170 BLACKGATE PRISONERS SET 35DC212 BATMAN (MV) 35DC171 NIGHTWING 35DC213 LEGION OF DOOM 35DC172 RED HOOD (MV) 35DC214 ROBIN & GOLIATH 35DC173 DEATHSTROKE (MV) 35DC215 CLAYFACE (MV) 1 BATMANMINIATURE GAME 35DC216 THE COURT OWLS CREW 35DC260 ROBIN (JASON TODD) 35DC217 OWLMAN (MV) 35DC262 BANE THE BAT 35DC218 JOHNNY QUICK (MV) 35DC263 -

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema John Saddington Submitted for the degree of PhD University of York Department of Sociology September 2010 Abstract This study examines representations of suicide in film. Based upon original research cataloguing 350 films it considers the ways in which suicide is portrayed and considers this in relation to gender conventions and cinematic traditions. The thesis is split into two sections, one which considers wider themes relating to suicide and film and a second which considers a number of exemplary films. Part I discusses the wider literature associated with scholarly approaches to the study of both suicide and gender. This is followed by quantitative analysis of the representation of suicide in films, allowing important trends to be identified, especially in relation to gender, changes over time and the method of suicide. In Part II, themes identified within the literature review and the data are explored further in relation to detailed exemplary film analyses. Six films have been chosen: Le Feu Fol/et (1963), Leaving Las Vegas (1995), The Killers (1946 and 1964), The Hustler (1961) and The Virgin Suicides (1999). These films are considered in three chapters which exemplify different ways that suicide is constructed. Chapters 4 and 5 explore the two categories that I have developed to differentiate the reasons why film characters commit suicide. These are Melancholic Suicide, which focuses on a fundamentally "internal" and often iII understood motivation, for example depression or long term illness; and Occasioned Suicide, where there is an "external" motivation for which the narrative provides apparently intelligible explanations, for instance where a character is seen to be in danger or to be suffering from feelings of guilt. -

Civic Subjects: Wordsworth, Tennyson, and the Victorian Laureateship

University of Alberta Civic Subjects: Wordsworth, Tennyson, and the Victorian Laureateship by Carmen Elizabeth Ellison A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Carmen Elizabeth Ellison Fall 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-62887-4 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-62887-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3Rd Revised and Expanded Edition 2010, Xii + 340 Pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00

New Resources for Clinicians Visit www.hogrefe.com for • Free sample chapters • Full tables of contents • Secure online ordering • Examination copies for teachers • Many other titles available Danny Wedding, Mary Ann Boyd, Ryan M. Niemiec NEW EDITION! Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3rd revised and expanded edition 2010, xii + 340 pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00 The popular and critically acclaimed teaching tool - movies as an aid to learning about mental illness - has just got even better! Now with even more practical features and expanded contents: full film index, “Authors’ Picks”, sample syllabus, more international films. Films are a powerful medium for teaching students of psychology, social work, medicine, nursing, counseling, and even literature or media studies about mental illness and psychopathology. Movies and Mental Illness, now available in an updated edition, has established a great reputation as an enjoyable and highly memorable supplementary teaching tool for abnormal psychology classes. Written by experienced clinicians and teachers, who are themselves movie aficionados, this book is superb not just for psychology or media studies classes, but also for anyone interested in the portrayal of mental health issues in movies. The core clinical chapters each use a fabricated case history and Mini-Mental State Examination along with synopses and scenes from one or two specific, often well-known “A classic resource and an authoritative guide… Like the very movies it films to explain, teach, and encourage discussion recommends, [this book] is a powerful medium for teaching students, about the most important disorders encountered in engaging patients, and educating the public. -

Legends of the Dark Knight: Norm Breyfogle: Volume 1 Free

FREE LEGENDS OF THE DARK KNIGHT: NORM BREYFOGLE: VOLUME 1 PDF Norm Breyfogle,Alan Grant | 520 pages | 04 Aug 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401258986 | English | United States LEGENDS OF THE DARK KNIGHT NORM BREYFOGLE VOLUME 2 HARDCOVER ( Pages) | eBay Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Alan Grant. John Wagner. Mike W. Barr. Jo Duffy. Robert Greenberger Goodreads Author. Batman AnnualDetective Comics, Get A Copy. Hardcoverpages. More Details Other Editions 4. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Legends of the Dark Knightplease sign up. Be the first to ask a question about Legends of the Dark Knight. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Mar 28, Keith rated it really liked it. So man, I have been waiting for this collection to exist for over 20 years. Batman which isn't collected here, but should be in subsequent volumes was my first-ever Legends of the Dark Knight: Norm Breyfogle: Volume 1 comic, and I reread it so many times in the intervening years I'm pretty sure I have it memorized. From that book forward, I was absolutely addicted to Norm Breyfogle's Batman -- the harsh angles, the incredible page layouts, the mix of narrative storytelling ability and an aggressive dynamism that I just don't even kno So man, I have been waiting for this collection to exist for over 20 years. -

Capes and Bats

CAT-TALES CCAPES AND BBATS CAT-TALES CCAPES AND BBATS By Wanders Nowhere This story is dedicated to Heath Ledger, my countryman, a light gone out of the world too soon. COPYRIGHT © 2011 BY Wanders Nowhere ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BATMAN, CATWOMAN, GOTHAM CITY, ET AL CREATED BY BOB KANE, PROPERTY OF DC ENTERTAINMENT, USED WITHOUT PERMISSION CAPES AND BATS Forward by Chris Dee .............................................................................. i Capes and Bats Rumblings ..................................................................................................1 The Coming Guest ....................................................................................7 The Paper Trail ........................................................................................13 Outbreak ...................................................................................................19 Breakthrough and Breakout ..................................................................29 A Gotham Welcome................................................................................39 He’s Laughing .........................................................................................47 Changes ....................................................................................................57 Knights of the Breakfast Table ..............................................................67 Walking the Line .....................................................................................75 Blitzkrieg ..................................................................................................83 -

Your Reading: a Booklist for Junior High and Middle School Students

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 299570 CS 211 536 AUTHOR Davis, James E., Ed.; Davis, Hazel K., Ed. TITLE Your Reading: A Booklist for Junior High and Middle School Students. Seventh Edition. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-5939-7 PUB DATE 88 NOTE 505p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Junior High and Middle School Booklist. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 59397, $10.95 member, $14.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC21 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; Elementary Secondary Education; Junior High Schools; *Literature Appreciation; Middle Schools; Reading Interests; *Reading Materials; Student Interests ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography, for junior high and middle school students, describes nearly 2,000 books to read for Pleasure, for school assignments, or merely to satisfy curiosity. Books included have been published mostly in the last five years and are divided into six major sections: fiction, drama, picture books for older readers, poetry, short story collections, and nonfiction. The fiction and nonfiction sections have been further subdivided into various categories; e.g. (1) abuse; (2) adventure; (3) animals and pets; (4) the arts; (5) Black experiences; (6) classics; (7) coming of age; (8) computers; (9) dating and love; (10) death and dying; (11) ecology; (12) ethnic experiences; (13) family situations; (14) -

Alice in the Country of Joker: Secret of the Star Jewel Vol 4 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ALICE IN THE COUNTRY OF JOKER: SECRET OF THE STAR JEWEL VOL 4 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Quinrose | 192 pages | 01 Mar 2014 | Seven Seas P.,N.Y. | 9781626920019 | English | New York, United States Alice in the Country of Joker: Secret of the Star Jewel Vol 4 PDF Book In his first outing, he is apprehended by Batman, Robin, and Superman. He was later seen as an adolescent who briefly took on the persona of the new Anarky. AV Club. Abattoir []. The father of her new daughter is initially unrevealed; however, Batman demonstrates great concern for the child and at one point asks to have Helena stay at his mansion. The character's actual first appearance was in Detective Comics October Batman characters. Batman October Duela Dent is a psychotic young woman with an obsession with the Joker. A month after Helena is placed with a new family, Catwoman asks Zatanna to erase her memories of Helena and change her mind back to a criminal mentality. Detective Comics January Batman Confidential 26 February was the character's first comic book appearance. London : Dorling Kindersley. She was originally characterized as a supervillain and adversary of Batman, but she has been featured in a series since the s which portrays her as an antiheroine , often doing the wrong things for the right reasons. Arkham Asylum: Living Hell 1 July Batman November Though Selina supports Batman for five years, she eventually joins the Regime after losing hope that the Regime could truly be stopped. Batman and Robin 26 August Grant Morrison Chris Burnham. Peter Merkel is a master contortionist and hypnotist who has fought Batman on many occasions. -

Scenes of Shame and Self-Deprecation in Contemporary

LOWEST OF THE LOW: SCENES OF SHAME AND SELF-DEPRECATION IN CONTEMPORARY SCOTTISH CINEMA Michael McCracken, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Harry Benshoff, Major Professor Sandra Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Sandra Spencer, Committee Member Melinda Levin, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television, and Film Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies McCracken, Michael. Lowest of the Low: Scenes of Shame and Self-Deprecation in Contemporary Scottish Cinema. Master of Science (Radio, Television, and Film), May 2008, 98 pp., references, 59 titles. This thesis explores the factors leading to the images of self-deprecation and shame in contemporary Scottish film. It would seem that the causes of these reoccurring motifs may be because the Scottish people are unable to escape from their past and are uneasy about the future of the nation. There is an internal struggle for both Scottish men and women, who try to adhere to their predetermined roles in Scottish culture, but this role leads to violence, alcoholism, and shame. In addition, there is also a fear for the future of the nation that represented in films that feature a connection between children and the creation of life with the death of Scotland’s past. This thesis will focus on films created under a recent boom in film production in Scotland beginning in 1994 till the present day. Copyright 2008 by Michael McCracken ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapters 1. SCOTTISH IDENTITY AND THE HISTORY OF SCOTTISH CINEMA..... -

Batman: Gotham City Chronicles

BGCC_Versus_Booklet_EN.indb 1 13/12/2018 14:19:12 CONNE CT IO N _3 5 M b / s BGCC_Versus_Booklet_EN.indb 2 13/12/2018 14:19:22 CONNE CT IO N _3 5 M b / s VERSUS MODE 1 * VERSUS MODE RULES P.4 2 * POWERS DESCRIPTION P.8 3 * MISSIONS P.23 _) 3 BGCC_Versus_Booklet_EN.indb 3 13/12/2018 14:19:42 I. VERSUS MODE RULES ] Versus invites two players, each equipped with a command post, to oppose each other in a skirmish mode. This is an expansion to the game system, the specificities of which take priority over the core game’s rules. In this game mode all miniatures, heroes or villains, are characters controlled by tiles. Consequently, the rules related to item management do not apply here. Contrary to the usual rules, the exertion limit of the defense spaces is 3 (rather than the usual 4). In this game mode the structure of a game turn is the same; however, the structure of each side is modified. The structure of the villain’s turn has been modified as follows. L ____________~ I I A A, STRUCTURE OF THE VILLAIN’S TURN: 1, UPKEEP VILLAIN’S TURN 1 ~ □□□ 1:1 ...... 1 STRUCTURE OF THE VILLAIN’S TURN 1 During this step, in addition to the usual rules, the , 1 UPKEEP VILLAIN’S TURN 1 villain recovers 2 activation potential points. To do _) so, they transfer 2 Activation Potential Discs (APDs) from their unavailable activation potential zone to their available activation potential zone. 2, TRIGGER THE START OF THE 1 , ' FIG._1 VILLAIN’S TURN EFFECTS _) 2 , 3 SPEND THE ACTIVATION POTENTIAL 1 _) 4, ~-.-~ +OR ....