Improving the Quality of Life of People with Dementia Through Dramatherapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schurken Im Batman-Universum Dieser Artikel Beschäftigt Sich Mit Den Gegenspielern Der ComicFigur „Batman“

Schurken im Batman-Universum Dieser Artikel beschäftigt sich mit den Gegenspielern der Comic-Figur ¹Batmanª. Die einzelnen Figuren werden in alphabetischer Reihenfolge vorgestellt. Dieser Artikel konzentriert sich dabei auf die weniger bekannten Charaktere. Die bekannteren Batman-Antagonisten wie z.B. der Joker oder der Riddler, die als Ikonen der Popkultur Verankerung im kollektiven Gedächtnis gefunden haben, werden in jeweils eigenen Artikeln vorgestellt; in diesem Sammelartikel werden sie nur namentlich gelistet, und durch Links wird auf die jeweiligen Einzelartikel verwiesen. 1 Gegner Batmans im Laufe der Jahrzehnte Die Gesamtheit der (wiederkehrenden) Gegenspieler eines Comic-Helden wird im Fachjargon auch als sogenannte ¹Schurken-Galerieª bezeichnet. Batmans Schurkengalerie gilt gemeinhin als die bekannteste Riege von Antagonisten, die das Medium Comic dem Protagonisten einer Reihe entgegengestellt hat. Auffällig ist dabei zunächst die Vielgestaltigkeit von Batmans Gegenspielern. Unter diesen finden sich die berüchtigten ¹geisteskranken Kriminellenª einerseits, die in erster Linie mit der Figur assoziiert werden, darüber hinaus aber auch zahlreiche ¹konventionelleª Widersacher, die sehr realistisch und daher durchaus glaubhaft sind, wie etwa Straûenschläger, Jugendbanden, Drogenschieber oder Mafiosi. Abseits davon gibt es auch eine Reihe äuûerst unwahrscheinlicher Figuren, wie auûerirdische Welteroberer oder extradimensionale Zauberwesen, die mithin aber selten geworden sind. In den frühesten Batman-Geschichten der 1930er und 1940er Jahre bekam es der Held häufig mit verrückten Wissenschaftlern und Gangstern zu tun, die in ihrem Auftreten und Handeln den Flair der Mobster der Prohibitionszeit atmeten. Frühe wiederkehrende Gegenspieler waren Doctor Death, Professor Hugo Strange und der vampiristische Monk. Die Schurken der 1940er Jahre bilden den harten Kern von Batmans Schurkengalerie: die Figuren dieser Zeit waren vor allem durch die Abenteuer von Dick Tracy inspiriert, der es mit grotesk entstellten Bösewichten zu tun hatte. -

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch from August 2019 – on with special thanks to Thomas Jarlvik The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 1) John Lee Hooker Part II There are 12 books (plus a Part II-book on Hooker) in the R&B Pioneers Series. They are titled The Great R&B Files at http://www.rhythm-and- blues.info/ covering the history of Rhythm & Blues in its classic era (1940s, especially 1950s, and through to the 1960s). I myself have used the ”new covers” shown here for printouts on all volumes. If you prefer prints of the series, you only have to printout once, since the updates, amendments, corrections, and supplementary information, starting from August 2019, are published in this special extra volume, titled ”Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files” (book #13). The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 2) The R&B Pioneer Series / CONTENTS / Updates & Amendments page 01 Top Rhythm & Blues Records – Hits from 30 Classic Years of R&B 6 02 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography 10 02B The World’s Greatest Blues Singer – John Lee Hooker 13 03 Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters 17 04 The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters 18 05 The Blues Giants of the 1950s – Twelve Great Legends 28 06 THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ’50s – Rhythm & Blues Harmony 48 07 Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ’n’ Roll – Idols Making Music History 62 08 Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons 66 09 The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers from the -

Dick Polich in Art History

ww 12 DICK POLICH THE CONDUCTOR: DICK POLICH IN ART HISTORY BY DANIEL BELASCO > Louise Bourgeois’ 25 x 35 x 17 foot bronze Fountain at Polich Art Works, in collaboration with Bob Spring and Modern Art Foundry, 1999, Courtesy Dick Polich © Louise Bourgeois Estate / Licensed by VAGA, New York (cat. 40) ww TRANSFORMING METAL INTO ART 13 THE CONDUCTOR: DICK POLICH IN ART HISTORY 14 DICK POLICH Art foundry owner and metallurgist Dick Polich is one of those rare skeleton keys that unlocks the doors of modern and contemporary art. Since opening his first art foundry in the late 1960s, Polich has worked closely with the most significant artists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. His foundries—Tallix (1970–2006), Polich of Polich’s energy and invention, Art Works (1995–2006), and Polich dedication to craft, and Tallix (2006–present)—have produced entrepreneurial acumen on the renowned artworks like Jeff Koons’ work of artists. As an art fabricator, gleaming stainless steel Rabbit (1986) and Polich remains behind the scenes, Louise Bourgeois’ imposing 30-foot tall his work subsumed into the careers spider Maman (2003), to name just two. of the artists. In recent years, They have also produced major public however, postmodernist artistic monuments, like the Korean War practices have discredited the myth Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC of the artist as solitary creator, and (1995), and the Leonardo da Vinci horse the public is increasingly curious in Milan (1999). His current business, to know how elaborately crafted Polich Tallix, is one of the largest and works of art are made.2 The best-regarded art foundries in the following essay, which corresponds world, a leader in the integration to the exhibition, interweaves a of technological and metallurgical history of Polich’s foundry know-how with the highest quality leadership with analysis of craftsmanship. -

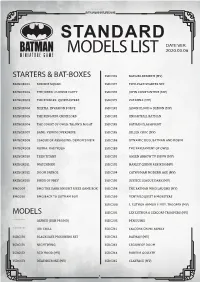

Batman Miniature Game Standard List

BATMANMINIATURE GAME STANDARD DATE VER. MODELS LIST 2020.03.06 35DC176 BATGIRL REBIRTH (MV) STARTERS & BAT-BOXES BATBOX001 SUICIDE SQUAD 35DC177 TWO-FACE STARTER SET BATBOX002 THE JOKER: CLOWNS PARTY 35DC178 JOHN CONSTANTINE (MV) BATBOX003 THE RIDDLER: QUIZMASTERS 35DC179 ZATANNA (MV) BATBOX004 MILITIA: INVASION FORCE 35DC181 JASON BLOOD & DEMON (MV) BATBOX005 THE PENGUIN: CRIMELORD 35DC182 KNIGHTFALL BATMAN BATBOX006 THE COURT OF OWLS: TALON’S NIGHT 35DC183 BATMAN FLASHPOINT BATBOX007 BANE: VENOM OVERDRIVE 35DC185 KILLER CROC (MV) BATBOX008 LEAGUE OF ASSASSINS: DEMON’S HEIR 35DC188 DYNAMIC DUO, BATMAN AND ROBIN BATBOX009 KOBRA: KALI YUGA 35DC189 THE PARLIAMENT OF OWLS BATBOX010 TEEN TITANS 35DC191 GREEN ARROW TV SHOW (MV) BATBOX011 WATCHMEN 35DC192 HARLEY QUINN REBIRTH (MV) BATBOX012 DOOM PATROL 35DC194 CATWOMAN MODERN AGE (MV) BATBOX013 BIRDS OF PREY 35DC195 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK (MV) BMG009 BMG THE DARK KNIGHT RISES GAME BOX 35DC198 THE BATMAN WHO LAUGHS (MV) BMG010 BMG BACK TO GOTHAM BOX 35DC199 VENTRILOQUIST & MOBSTERS 35DC200 L. LUTHOR ARMOR & HVY. TROOPER (MV) MODELS 35DC201 LEX LUTHOR & LEXCORP TROOPERS (MV) ¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨ ALFRED (DKR PROMO) 35DC205 PENGUINS “““““““““ JOE CHILL 35DC211 FALCONE CRIME FAMILY 35DC170 BLACKGATE PRISONERS SET 35DC212 BATMAN (MV) 35DC171 NIGHTWING 35DC213 LEGION OF DOOM 35DC172 RED HOOD (MV) 35DC214 ROBIN & GOLIATH 35DC173 DEATHSTROKE (MV) 35DC215 CLAYFACE (MV) 1 BATMANMINIATURE GAME 35DC216 THE COURT OWLS CREW 35DC260 ROBIN (JASON TODD) 35DC217 OWLMAN (MV) 35DC262 BANE THE BAT 35DC218 JOHNNY QUICK (MV) 35DC263 -

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema John Saddington Submitted for the degree of PhD University of York Department of Sociology September 2010 Abstract This study examines representations of suicide in film. Based upon original research cataloguing 350 films it considers the ways in which suicide is portrayed and considers this in relation to gender conventions and cinematic traditions. The thesis is split into two sections, one which considers wider themes relating to suicide and film and a second which considers a number of exemplary films. Part I discusses the wider literature associated with scholarly approaches to the study of both suicide and gender. This is followed by quantitative analysis of the representation of suicide in films, allowing important trends to be identified, especially in relation to gender, changes over time and the method of suicide. In Part II, themes identified within the literature review and the data are explored further in relation to detailed exemplary film analyses. Six films have been chosen: Le Feu Fol/et (1963), Leaving Las Vegas (1995), The Killers (1946 and 1964), The Hustler (1961) and The Virgin Suicides (1999). These films are considered in three chapters which exemplify different ways that suicide is constructed. Chapters 4 and 5 explore the two categories that I have developed to differentiate the reasons why film characters commit suicide. These are Melancholic Suicide, which focuses on a fundamentally "internal" and often iII understood motivation, for example depression or long term illness; and Occasioned Suicide, where there is an "external" motivation for which the narrative provides apparently intelligible explanations, for instance where a character is seen to be in danger or to be suffering from feelings of guilt. -

Civic Subjects: Wordsworth, Tennyson, and the Victorian Laureateship

University of Alberta Civic Subjects: Wordsworth, Tennyson, and the Victorian Laureateship by Carmen Elizabeth Ellison A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Carmen Elizabeth Ellison Fall 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-62887-4 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-62887-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Productor No Identificado 2-2009R

Código Titulo Interprete 1887 I AM NOT IN LOVE 10 CC 90447 CANDY EVERYBODY 10,000 MANIACS 114056 DON T TALK 10,000 MANIACS 110619 BICICLETAS 11 Y 20 100752 LA ULTIMA CENA 12 DISCIPULOS 83485 QUITATE TU PA PONERME YO 12 DISCIPULOS 114057 CONCIENCIA EN BABYLON 12 TRIBUS 111526 SIMON SAYS 1910 FRUITGUM COMPANY 111529 BROKEN WINGS 2 PAC 105717 CHANGES 2 PAC 101756 GET READY FOR THIS 2 UNLIMITED 93146 NO LIMIT 2 UNLIMITED 64847 MR PERSONALITY 20 FINGERS 81734 YOU ARE LIKE 20 FINGERS 99975 YOU GOTTA LIECK IT 20 FINGERS 81199 CUANTO MAS 20/20 114058 PUEDO VOLAR 20/20 110621 DONT TRUST ME 3 OH 3 113280 STARSTRUKK 3 OH 3 FT KATY PERRY 104573 ATTACK 30 SECONDS TO MARS 103505 FROM YESTERDAY 30 SECONDS TO MARS 114059 KINGS AND QUEENS 30 SECONDS TO MARS 100754 THE KILL 30 SECONDS TO MARS 114060 BACK WHERE YOU BELONG 38 SPECIAL 64848 CAUGHT UP IN YOU 38 SPECIAL 100755 Anything 3T 79883 STUCK ON YOU 3T 110622 DONT YOU LOVE ME 49 ERS 87745 CANDY SHOP 50 CENT 103506 AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT FEAT JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 101759 A NOCHE 5TA ESTACION 112253 DUELE 5TA ESTACION 114010 ENGAÑAME 5TA ESTACION 114028 MIRADAS 5TA ESTACION 97502 PENSANDO EN TI 5TA ESTACION 109580 QUE TE QUIERA 5TA ESTACION 111104 RECUERDAME 5TA ESTACION 114642 SIN FRENOS 5TA ESTACION 112911 TE QUIERO 5TA ESTACION 102701 ACUARIO 5TH DIMENSION THE 81903 CAMINANDO BAJO EL SOL 5TH DIMENSION THE 58853 LAST NIGHT I DID N GET TO 5TH DIMENSION THE 101765 NUNCA MI AMOR 5TH DIMENSION THE 112365 LINDA PRINCESA 5TO PISO 105725 MIRA COMO VA 5TO PISO 76067 DE NUEVO ABRAZAME 6 DEL VALLENATO LOS 104807 LA -

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Download (7MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] University of Glasgow French Department February 2004 Death as a Symbol of Loss and Principle of Regeneration in the Works of Villiers de L’Isle-Adam Lesley Anne Rankin Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ProQuest Number: 10753973 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10753973 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Integrating Historic Preservation Into the Public Primary And

INTEGRATING HISTORIC PRESERVATION INTO THE PUBLIC PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOL CURRICULUM by MIGNON LAWTON BROCKENBROUGH (Under the Direction of John C. Waters) ABSTRACT This thesis explores the various educational efforts to introduce Historic Preservation into primary and secondary public school curricula both through heritage education activities and a unique example of comprehensive historic preservation education as the foundation for an academic academy. The thesis compares and contrasts two approaches to incorporating historic preservation into the public school system (heritage education and historic preservation education), and examines a noteworthy case study of each alternative. It advocates for the replication and proliferation of the integrated academy model as a means of promoting a commitment to principles and values of Historic Preservation, career choices within the preservation trades and associated fields, and as a well-documented method of involving, engaging, retaining, and enabling success within a student body with diverse interests and abilities. INDEX WORDS: Historic Preservation, Education, Massie Heritage Center, Brooklyn High School for the Arts, Career Academies, Contextual Teaching and Learning INTEGRATING HISTORIC PRESERVATION INTO THE PUBLIC PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOL CURRICULUM by MIGNON LAWTON BROCKENBROUGH B.S., Vanderbilt University, 1997 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION ATHENS, GEORGIA 2006 © 2006 Mignon Lawton Brockenbrough All Rights Reserved INTEGRATING HISTORIC PRESERVATION INTO THE PUBLIC PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOL CURRICULUM by MIGNON LAWTON BROCKENBROUGH Major Professor: John C. Waters Committee: James Reap Thomas Dyer Elizabeth Lyon Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2006 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank John C. -

Final Recovery Plan Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax Traillii Extimus)

Final Recovery Plan Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) August 2002 Prepared By Southwestern Willow Flycatcher Recovery Team Technical Subgroup For Region 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103 Approved: Date: 018085 Disclaimer Recovery Plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. Approved Recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Some of the techniques outlined for recovery efforts in this plan are completely new regarding this subspecies. Therefore, the cost and time estimates are approximations. Citations This document should be cited as follows: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Southwestern Willow Flycatcher Recovery Plan. Albuquerque, New Mexico. i-ix + 210 pp., Appendices A-O Additional copies may be purchased from: Fish and Wildlife Service Reference Service 5430 Governor Lane, Suite 110 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 301/492-6403 or 1-800-582-3421 i 018086 This Recovery Plan was prepared by the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher Recovery Team, Technical Subgroup: Deborah M.