Landowner's Response and Adaptation to Large Scale Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority

For Reference Only T H E SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority Vol. LXXI 25th July, 2016 No. 50 Swk. L. N. 204 THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDINANCE THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDER, 2016 (Made under section 3) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Majlis Mesyuarat Kerajaan Negeri by section 3 of the Administrative Areas Ordinance [Cap. 34], the following Order has been made: Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Administrative Areas Order, 2016, and shall be deemed to have come into force on the 1st day of August, 2015. Administrative Areas 2. Sarawak is divided into the divisions, districts and sub-districts specified and described in the Schedule. Revocation 3. The Administrative Areas Order, 2015 [Swk. L.N. 366/2015] is hereby revokedSarawak. Lawnet For Reference Only 26 SCHEDULE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS KUCHING DIVISION (1) Kuching Division Area (Area=4,195 km² approximately) Commencing from a point on the coast approximately midway between Sungai Tambir Hulu and Sungai Tambir Haji Untong; thence bearing approximately 260º 00′ distance approximately 5.45 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.1 kilometres to the junction of Sungai Tanju and Loba Tanju; thence in southeasterly direction along Loba Tanju to its estuary with Batang Samarahan; thence upstream along mid Batang Samarahan for a distance approximately 5.0 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.8 kilometres to the midstream of Loba Batu Belat; thence in westerly direction along midstream of Loba Batu Belat to the mouth of Loba Gong; thence in southwesterly direction along the midstream of Loba Gong to a point on its confluence with Sungai Bayor; thence along the midstream of Sungai Bayor going downstream to a point at its confluence with Sungai Kuap; thence upstream along mid Sungai Kuap to a point at its confluence with Sungai Semengoh; thence upstream following the mid Sungai Semengoh to a point at the midstream of Sungai Semengoh and between the middle of survey peg nos. -

Sustainable Palm Oil Cluster Saratok & Budu

PF824 MSPO Public Summary Report Revision 0 (Aug 2017) MALAYSIAN SUSTAINABLE PALM OIL – SURVEILLANCE ASSESSMENT ASA 4 Public Summary Report LEMBAGA MINYAK SAWIT MALAYSIA (MPOB) CAWANGAN SARATOK Client company Address: Pejabat MPOB Cawangan Saratok, 1st & 2nd Floor, Taman Muhibbah, 95400 Saratok. Certification Unit: Sustainable Palm Oil Cluster (SPOC) Saratok & Budu (Q12) Location of Certification Unit: Saratok, Sarawak, Malaysia Report prepared by: MUHAMAD NAQIUDDIN MAZELI (Lead Auditor) Report Number: 9673713 Assessment Conducted by: BSI Services Malaysia Sdn Bhd, Suite 29.01 Level 29 The Gardens North Tower, Mid Valley City Lingkaran Syed Putra , 59200 Kuala Lumpur Tel +603 2242 4211 Fax +603 2242 4218 www.bsigroup.com Page 1 of 43 PF824 MSPO Public Summary Report Revision 0 (Aug 2017) TABLE of CONTENTS Page No Section 1: Executive Summary ........................................................................................ 3 1.1 Organizational Information and Contact Person ........................................................ 3 1.2 Certification Information ......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Location of Certification Unit ................................................................................... 3 1.4 Plantings & Cycle ................................................................................................... 4 1.5 FFB Production (Actual) and Projected (tonnage) ...................................................... 4 1.6 Certified CPO / PK Tonnage -

Deforestation, Forest Degradation and Readiness of Local People Of

Sains Malaysiana 43(10)(2014): 1461–1470 Deforestation, Forest Degradation and Readiness of Local People of Lubuk Antu, Sarawak for REDD+ (Penyahhutanan, Dedgrasi Hutan dan Kesediaan Penduduk Tempatan dari Lubuk Antu, Sarawak bagi REDD +) MUI-HOW PHUA*, WILSON WONG, MEA HOW GOH, KAMLISA UNI KAMLUN, JULIUS KODOH, STEPHEN TEO, FAZILAH MAJID COOKE & SATOSHI TSUYUKI ABSTRACT Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation-plus (REDD+) is considered as an important mitigation strategy against global warming. However, the implementation of REDD+ can adversely affect local people who have been practicing shifting cultivation for generations. We analyzed Landsat-5 Thematic Mapper images of 1990 and 2009 to quantifying deforestation and forest degradation at Lubuk Antu District, a typical rural area of Sarawak, Malaysia. The results showed significant loss of intact forest at 0.9% per year, which was substantially higher than the rate of Sarawak. There were increases of oil palm and rubber areas but degraded forest, the second largest land cover type, had increased considerably. The local people were mostly shifting cultivators, who indicated readiness of accepting the REDD+ mechanism if they were given compensation. We estimated the monthly willingness to accept (WTA) at RM462, which can be considered as the opportunity cost of foregoing their existing shifting cultivation. The monthly WTA was well correlated with their monthly household expenses. Instead of cash payment, rubber cultivation scheme was the most preferred form of compensation. Keywords: Deforestation; forest degradation; REDD+; shifting cultivation; willingness to accept ABSTRAK Pengurangan pelepasan daripada penyahhutanan dan degradasi hutan-plus (REDD+) dianggap sebagai strategi mitigasi penting dalam menangani pemanasan global. -

Development and Limitations of the Livelihoods and Natural Resources in Gerigat, Sarawak, Malaysia

ILUNRM – report Gerigat, Malaysia April 2008 Development and limitations of the livelihoods and natural resources in Gerigat, Sarawak, Malaysia ILUNRM‐Course Faculty of LIFE Sciences University of Copenhagen, Denmark Frederiksberg, 10th of April 2008 Elzélina van Melle Ida Tingman Møller Berdi Aaltje Bernardette Doornebosch Laust Christian Prosch Sidelmann Nielsen Supervisors: Andreas de Neergaard and Michael Eilenberg 1 ILUNRM – report Gerigat, Malaysia April 2008 Contents Contents ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Contributing authors ................................................................................................................................. 6 Abstract .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Research questions .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Background ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Language Use and Attitudes As Indicators of Subjective Vitality: the Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia

Vol. 15 (2021), pp. 190–218 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24973 Revised Version Received: 1 Dec 2020 Language use and attitudes as indicators of subjective vitality: The Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia Su-Hie Ting Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Andyson Tinggang Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Lilly Metom Universiti Teknologi of MARA The study examined the subjective ethnolinguistic vitality of an Iban community in Sarawak, Malaysia based on their language use and attitudes. A survey of 200 respondents in the Song district was conducted. To determine the objective eth- nolinguistic vitality, a structural analysis was performed on their sociolinguistic backgrounds. The results show the Iban language dominates in family, friend- ship, transactions, religious, employment, and education domains. The language use patterns show functional differentiation into the Iban language as the “low language” and Malay as the “high language”. The respondents have positive at- titudes towards the Iban language. The dimensions of language attitudes that are strongly positive are use of the Iban language, Iban identity, and intergenera- tional transmission of the Iban language. The marginally positive dimensions are instrumental use of the Iban language, social status of Iban speakers, and prestige value of the Iban language. Inferential statistical tests show that language atti- tudes are influenced by education level. However, language attitudes and useof the Iban language are not significantly correlated. By viewing language use and attitudes from the perspective of ethnolinguistic vitality, this study has revealed that a numerically dominant group assumed to be safe from language shift has only medium vitality, based on both objective and subjective evaluation. -

A Study on Trend of Logs Production and Export in the State of Sarawak, Malaysia

International Journal of Marketing Studies www.ccsenet.org/ijms A Study on Trend of Logs Production and Export in the State of Sarawak, Malaysia Pakhriazad, H.Z. (Corresponding author) & Mohd Hasmadi, I Department of Forest Management, Faculty of Forestry, Universiti Putra Malaysia 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-3-8946-7225 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This study was conducted to determine the trend of logs production and export in the state of Sarawak, Malaysia. The trend of logs production in this study referred only to hill and peat swamp forest logs production with their species detailed production. The trend of logs export was divided into selected species and destinations. The study covers the analysis of logs production and export for a period of ten years from 1997 to 2006. Data on logs production and export were collected from statistics published by the Sarawak Timber Industry Development Corporation (Statistic of Sarawak Timber and Timber Product), Sarawak Timber Association (Sarawak Timber Association Review), Hardwood Timber Sdn. Bhd (Warta) and Malaysia Timber Industry Board (MTIB). The trend of logs production and export were analyzed using regression model and times series. In addition, the relation between hill and peat swamp forest logs production with their species and trend of logs export by selected species and destinations were conducted using simple regression model and descriptive statistical analysis. The results depicted that volume of logs production and export by four major logs producer (Sibu division, Bintulu division, Miri division and Kuching division) for hill and peat swamp forest showed a declining trend. Result showed that Sibu division is the major logs producer for hill forest while Bintulu division is the major producer of logs produced for the peat swamp forest. -

The Response of the Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol21, No 6, pp 977 – 988, 2000 Globalizationand democratization: the responseo ftheindigenous peoples o f Sarawak SABIHAHOSMAN ABSTRACT Globalizationis amulti-layered anddialectical process involving two consequenttendencies— homogenizing and particularizing— at the same time. Thequestion of howand in whatways these contendingforces operatein Sarawakand in Malaysiaas awholeis therefore crucial in aneffort to capture this dynamic.This article examinesthe impactof globalizationon the democra- tization process andother domestic political activities of the indigenouspeoples (IPs)of Sarawak.It shows howthe democratizationprocess canbe anempower- ingone, thus enablingthe actors to managethe effects ofglobalization in their lives. Thecon ict betweenthe IPsandthe state againstthe depletionof the tropical rainforest is manifested in the form of blockadesand unlawful occu- pationof state landby the former as aform of resistance andprotest. Insome situations the federal andstate governmentshave treated this actionas aserious globalissue betweenthe international NGOsandthe Malaysian/Sarawakgovern- ment.In this case globalizationhas affected boththe nation-state andthe IPs in different ways.Globalization has triggered agreater awareness of self-empow- erment anddemocratization among the IPs. These are importantforces in capturingsome aspects of globalizationat the local level. Globalization is amulti-layered anddialectical process involvingboth homoge- nization andparticularization, ie the rise oflocalism in politics, economics, -

Getting the Malaysian Native Penan Community Do Business for Inclusive Development and Sustainable Livelihood

PROSIDING PERKEM 10, (2015) 434 – 443 ISSN: 2231-962X Getting The Malaysian Native Penan Community Do Business For Inclusive Development And Sustainable Livelihood Doris Padmini Selvaratnam Faculty of Economics and Management, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Email: [email protected] Hamidah Yamat Faculty of Education Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Email: [email protected] Sivapalan Selvadurai Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Email: [email protected] Novel Lyndon Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Email: [email protected] ABRSTRACT The Penan are a minority indigenous community in Sarawak, Malaysia. Traditionally the avatars of highland tropical forests, today they are displaced, in a foreign setting, forced to pick up new trade and skills to survive the demands of national economic advancement. Forced relocation did not promise jobs, but necessity of survival forced them to submit to menial jobs at construction sites and plantations to ensure that food is available for the household. Today, a new model of social entrepreneurship is introduced to the Penan to help access their available skills and resources to encourage the development of business endeavors to ensure inclusive development and sustainable livelihood of the Penan. Interviews and field observation results analysed show that the Penan are not afraid of setting their own markers in the business arena. Further analysis of the situation show that the success of the business is reliant not just on the resilience and hard work of the Penan but also the friendly business environment. Keywords: Native, Penan, Malaysia, Business, Inclusive Development, Sustainable Livelihood THE PENAN’ NEW SETTLEMENT AWAY FROM THE HIGHLAND TROPICAL FOREST The Penan community is indigenous to the broader Dayak group in Sarawak, Malaysia. -

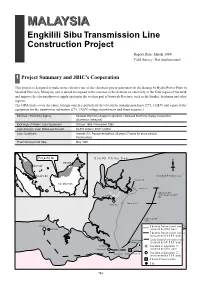

Post-Evaluation Report for ODA Loan Projects 1999

MALAYSIAMALAYSIA Engkilili Sibu Transmission Line Construction Project Report Date: March 1999 Field Survey: Not implemented 1 Project Summary and JBIC's Cooperation This project is designed to make more effective use of the electrical power generators in the Batang Ai Hydro Power Plant in Sarawak Province, Malaysia, and is aimed to respond to the increase in the demand on electricity in the Sibu region of Sarawak and improve the electrical power supply system in the western part of Sarawak Province, such as the Sarikei, Sri Aman and other regions. The ODA loan covers the entire foreign currency portion for the electricity transmission lines (275, 132kV) and a part of the equipment for the transformer substation (275, 132kV voltage transformers and shunt reactors.) Borrower / Executing Agency Sarawak Electricity Supply Corporation / Sarawak Electricity Supply Corporation (Guarantor: Malaysia) Exchange of Notes / Loan Agreement October 1986 / November 1986 Loan Amount / Loan Disbursed Amount ¥4,357 million / ¥3,811 million Loan Conditions Interest: 5%, Repayment period: 25 years (7 years for grace period), Partial untied Final Disbursement Date May 1990 Project Site Sourth China Sea N BRUNEI MALAYSIA SINGAPORE (Sarawak Province)� Bandong S/S KALIMANTAN SIBU Deshon S/S 132KV 2circuits� SARIKEI (275KV designed partly)� 34km Kemantan S/S Sarikei S/S 275KV 2circuits� 120km Matang S/S Electricity Transmission Lines � KUCHING (covered by ODA loan) Electricity Transmission Lines � (not covered by ODA loan) (Ulu Ai Hydro� Existing Electricity Transmission Lines� planed P/S)� (covered by 8th ODA loan) SRI AMAN Transformer Substation � Sri Aman S/S (covered by ODA loan) Engkilili S/S Batang Ai Hydro P/S Transformer Substation � (not covered by ODA loan) Electric Power Station City 746 2 Evaluation Results (1) Project Implementation (i) Project Scope The scope of this as a whole project was completed mostly in accordance with the original plan. -

Revision of the Sundaland Species of the Genus Dysphaea Selys, 1853 Using Molecular and Morphological Methods, with Notes on Allied Species (Odonata: Euphaeidae)

Zootaxa 3949 (4): 451–490 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3949.4.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:B3123099-882F-4C42-B83B-2BA1C2906F65 Revision of the Sundaland species of the genus Dysphaea Selys, 1853 using molecular and morphological methods, with notes on allied species (Odonata: Euphaeidae) MATTI HÄMÄLÄINEN1, RORY A. DOW2 & FRANK R. STOKVIS3 Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The Sundaland species of the genus Dysphaea were studied using molecular and morphological methods. Four species are recognized: D. dimidiata Selys, D. lugens Selys, D. ulu spec. nov. (holotype ♂, from Borneo, Sarawak, Miri division, Upper Baram, Sungai Pejelai, Ulu Moh, 24 viii 2014; deposited in RMNH) and D. vanida spec. nov. (holotype ♂, from Thailand, Ranong province, Khlong Nakha, Khlong Bang Man, 12–13 v 1999; deposited in RMNH). The four species are described and illustrated for both sexes, with keys provided. The type specimens of the four Dysphaea taxa named by E. de Selys Longchamps, i.e. dimidiata, limbata, semilimbata and lugens, were studied and their taxonomic status is dis- cussed. Lectotypes are designated for D. dimidiata and D. limbata. D. dimidiata is recorded from Palawan (the Philip- pines) for the first time. A molecular analysis using three markers (COI, 16S and 28S) is presented. This includes specimens of three Sundaland species of the genus (D. -

Senarai Cawangan Jabatan Dan Agensi Persekutuan Di Sarawak

SENARAI KETUA CAWANGAN JABATAN DAN AGENSI PERSEKUTUAN DI SARAWAK 1 JABATAN PENILAIAN DAN PERKHIDMATAN HARTA SARAWAK BIL CAWANGAN ALAMAT NAMA KETUA CAWANGAN JAWATAN/GRED EMEL NO TEL NO FAKS JABATAN PENILAIAN DAN PERKHIDMATAN HARTA KUCHING, TKT.2, WISMA HONG, 082-255859/ 1 KUCHING ROSLIMA BINTI TAHA PENILAI DAERAH KUCHING/W44 [email protected] 082-256117 WISMA HONG, BATU 2 ¾, JALAN ROCK, 93200 KUCHING 082-235144 JABATAN PENILAIAN DAN PERKHIDMATAN HARTA SIBU, LOT 903, BLOK 7, SIBU TOWN 084-327407/ 2 SIBU LISA LOW SEOW WEI PENILAI DAERAH SIBU/W44 [email protected] 084-327064 DISTRICT, NO.60, JALAN TIONG HUA, 96000 SIBU 084-327132 JABATAN PENILAIAN DAN PERKHIDMATAN HARTA MIRI, TKT. 10, YU LAN PLAZA, JALAN 085-427226/ 3 MIRI SONG MUI KIE PENILAI DAERAH MIRI/W44 [email protected] 085-415226 BROOKE, 98000 MIRI 085-425226 2 KEMENTERIAN PERDAGANGAN DALAM NEGERI DAN HAL EHWAL PENGGUNA NEGERI SARAWAK BIL CAWANGAN ALAMAT NAMA KETUA CAWANGAN JAWATAN/GRED EMEL NO TEL NO FAKS PEJABAT KEMENTERIAN PERDAGANGAN DALAM NEGERI DAN HAL EHWAL PENGGUNA PENOLONG PEGAWAI 1 SERIAN SUB-CAWANGAN SERIAN, PUSAT REKREASI SABERKAS CAWANGAN KEDUP SERIAN, D/A YUSOF BIN SMAIL [email protected] - - PENGUATKUASA/KP29 JALAN D.O. AREA, 94700 SERIAN, SARAWAK PEJABAT KEMENTERIAN PERDAGANGAN DALAM NEGERI DAN HAL EHWAL PENGGUNA 2 SRI AMAN CAWANGAN SRI AMAN, BANGUNAN PERSEKUTUAN GUNASAMA, BLOK II & III, JALAN PELANI ANAK KEMITI PEGAWAI PENGUATKUASA/KP41 [email protected] 083-323836 083-323150 KEJATAU, P.O BOX 425, 95000 SRI AMAN, SARAWAK PEJABAT KEMENTERIAN PERDAGANGAN -

Community-Investor Business Models: Lessons from the Oil Palm Sector in East Malaysia

Community-investor business models: Lessons from the oil palm sector in East Malaysia Fadzilah Majid Cooke, Sumei Toh and Justine Vaz Enabling poor rural people to overcome poverty Community-investor business models: Lessons from the oil palm sector in East Malaysia Fadzilah Majid Cooke, Sumei Toh and Justine Vaz Community-investor business models: Lessons from the oil palm sector in East Malaysia First published by the International Institute for Environment and Development (UK) in 2011 Copyright © International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) All rights reserved ISBN: 978-1-84369-841-8 ISSN: 2225-739X For copies of this publication, please contact IIED: International Institute for Environment and Development 80-86 Gray’s Inn Road London WC1X 8NH United Kingdom Email: [email protected] www.iied.org/pubs IIED order no.: 12570IIED A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Citation: Majid Cooke, F., Toh, S. and Vaz, J. (2011) Community-investor business models: Lessons from the oil palm sector in East Malaysia. IIED/IFAD/FAO/ Universiti Malaysia Sabah, London/Rome/Kota Kinabalu. Cover photo: A worker collects loose fruit at an oil palm plantation in Malaysia © Puah Sze Ning (www.szening.com) Cartography: C. D’Alton Design: Smith+Bell (www.smithplusbell.com) Printing: Park Communications (www.parkcom.co.uk). Printed with vegetable oil based inks on Chorus Lux, an FSC certified paper bleached using a chlorine free process. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), or the Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS).