Breaking Bold Habit 1-Perception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Dormant Potential: Strategies for Advancing Human Development In

Dormant potential Strategies for advancing human development in Namibia Zachary Donnenfeld and Courtney Crookes Since gaining independence in 1990, Namibia has sustained rapid economic growth at an average of 4.5% a year, well above the average experienced by other upper-middle-income countries in Africa (2.8%) and nearly a percentage point higher than the continental average (3.7%). However, this economic growth has not been accompanied by proportional increases in service delivery. Namibia ranks at or near the bottom of its upper-middle-income peer group on a number of dimensions of human well-being, such as undernutrition, access to improved sanitation and average number of years of education. This report explores options for improving human development outcomes in Namibia to 2040 using the International Futures (IFs) forecasting system. SOUTHERN AFRICA REPORT 11 | SEPTEMBER 2017 After a bloody and protracted liberation struggle – and with significant Recommendations influence from the international community – Namibia declared its Invest in health extension independence on 21 March 1990.1 Since then the country has averaged programmes that address gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 4.5% a year, largely on the back communicable and non- of its extractive industries and budding tourism economy. The country’s communicable diseases. economy has grown about a percentage point faster than the average African country over the last 25 years and, despite a substantial downtick Improve the flow of students in 2016 (when its estimated yearly growth was 1.6%), the International through the education pipeline. Monetary Fund (IMF) expects Namibia’s growth to average roughly 4.5% Increase access to family from 2017 to 2021.2 planning. -

Whose History and by Whom: an Analysis of the History of Taiwan In

WHOSE HISTORY AND BY WHOM: AN ANALYSIS OF THE HISTORY OF TAIWAN IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE PUBLISHED IN THE POSTWAR ERA by LIN-MIAO LU (Under the Direction of Joel Taxel) ABSTRACT Guided by the tenet of sociology of school knowledge, this study examines 38 Taiwanese children’s trade books that share an overarching theme of the history of Taiwan published after World War II to uncover whether the seemingly innocent texts for children convey particular messages, perspectives, and ideologies selected, preserved, and perpetuated by particular groups of people at specific historical time periods. By adopting the concept of selective tradition and theories of ideology and hegemony along with the analytic strategies of constant comparative analysis and iconography, the written texts and visual images of the children’s literature are relationally analyzed to determine what aspects of the history and whose ideologies and perspectives were selected (or neglected) and distributed in the literary format. Central to this analysis is the investigation and analysis of the interrelations between literary content and the issue of power. Closely related to the discussion of ideological peculiarities, historians’ research on the development of Taiwanese historiography also is considered in order to examine and analyze whether the literary products fall into two paradigms: the Chinese-centric paradigm (Chinese-centricism) and the Taiwanese-centric paradigm (Taiwanese-centricism). Analysis suggests a power-and-knowledge nexus that reflects contemporary ruling groups’ control in the domain of children’s narratives in which subordinate groups’ perspectives are minimalized, whereas powerful groups’ assumptions and beliefs prevail and are perpetuated as legitimized knowledge in society. -

Sorcerer Society" by Rob Cesternino

30 ROCK "Sorcerer Society" by Rob Cesternino Cell: (323)382-3083 [email protected] ACT ONE FADE IN: INT. STUDIO BACKSTAGE - MORNING LIZ walks through the hallways of 30 Rock. JENNA spots Liz and runs over. JENNA Today is the greatest day of my life. My IMDB star meter is up four percent! LIZ Are they finally airing your episode of "Competitive Eating with the Stars". JENNA No, that was last month. Last night I was a guest star on an episode of the new NBC series, “Sorcerer Society”! FLASHBACK TO: INT. SORCERY CLASSROOM - DAY Jenna is dressed as a sorceress standing before a classroom at Sorcery High School. JENNA I'm Mrs. Mongothsbeard, I’ll be substituting for your regular sorcery teacher, who was caught making a very bad potion called “crystal meth”. CUT BACK TO: INT. LIZ’S OFFICE - CONTINUOUS Liz and Jenna walk into Liz’s office. LIZ Jenna, that show sucks! It totally bastardizes the books. 2. JENNA "Sorcerer Society" was a book? Liz points to her shelf of thick “Sorcerer Society” books. LIZ Those books were my only friends in junior high school... besides the teachers. JACK bursts into Liz's office carrying one of the trades. JACK Everybody is buzzing about Jenna this morning and, for once, it’s not because of some compromising photos on “TMZ”. JENNA This is the best thing to happen to me since they dropped the class action lawsuit against my "Jenna Maroney Birth Control Powder"! JACK “Sorcerer Society” is a runaway hit. It’s like "Twilight" meets "Harry Potter" meets "Heroes", before it jumped the shark. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Representations of Female Nerds in U.S.-American Sitcoms“ verfasst von / submitted by Beate Reichl, BA BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2018 / Vienna 2018 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 844 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Anglophone Literatures and Cultures degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Alexandra Ganser-Blumenau Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my supervisor, Prof. Alexandra Ganser-Blumenau. Then, I would like to offer my special thanks to my aunt, Susanne Reichl, for being my continuous role model and adviser. Finally yet importantly, I wish to acknowledge the never-ending support provided by my husband, Manuel Engel, my parents and close friends. Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................. i 1 Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 2 Representations of the Nerd ...................................................................... 2 Representation .................................................................................... 2 Stereotypes ......................................................................................... 3 The Nerd -

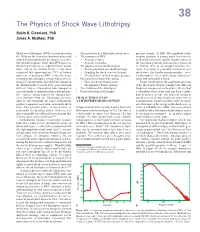

Ch038: the Physics of Shock Wave Lithotripsy

315-366_Smith_Ch38-41_Prt4 6/29/06 6:09 PM Page 317 38 The Physics of Shock Wave Lithotripsy Robin O. Cleveland, PhD James A. McAteer, PhD Shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) was introduced in • Characteristics of a lithotriptor shock wave pressure around –10 MPa. The amplitude of the the 1980s for the treatment of urinary stones and • The acoustics of SWL negative pressure is always much less than the earned near-instantaneous acceptance as a first- • Acoustics primer peak positive pressure, and the negative phase of line treatment option.1 Since then SWL has revo- • Acoustic cavitation the waveform generally does not have a shock in lutionized treatment in nephrolithiasis world- • The physics of clinical lithotriptors it—that is, there is no abrupt transition. The wide, and in the United States, it has been • Shock generation and shock focusing entire 5 µs pulse is generally referred to as a estimated that approximately 70% of kidney • Coupling the shock wave to the body shock wave, shock pulse or pressure pulse—tech- stones are treated using SWL.2 Over the years, • The focal zone of high acoustic pressure nically, however, it is only the sharp leading tran- lithotripsy has undergone several waves of tech- • Mechanisms of shock wave action sition that is formally a shock. nological advancement, but with little change in • How shock wave break stones Figure 38-1B shows the amplitude spectrum the fundamentals of shock wave generation and • Mechanisms of tissue damage of the shock pulse (that is, it displays the different delivery. That is, lithotriptors have changed in • The evolution of the lithotriptor frequency components in the pulse). -

30 Rock and Philosophy: We Want to Go to There (The Blackwell

ftoc.indd viii 6/5/10 10:15:56 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 6/5/10 10:15:35 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Terminator and Philosophy Edited by Richard Brown and Family Guy and Philosophy Kevin Decker Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Heroes and Philosophy The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by David Kyle Johnson Edited by Jason Holt Twilight and Philosophy Lost and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and Edited by Sharon Kaye J. Jeremy Wisnewski 24 and Philosophy Final Fantasy and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Edited by Jason P. Blahuta and Hart Weed, and Ronald Weed Michel S. Beaulieu Battlestar Galactica and Iron Man and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White Edited by Jason T. Eberl Alice in Wonderland and The Offi ce and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Edited by Richard Brian Davis Batman and Philosophy True Blood and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Edited by George Dunn and Robert Arp Rebecca Housel House and Philosophy Mad Men and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Edited by Rod Carveth and Watchman and Philosophy James South Edited by Mark D. White ffirs.indd ii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY WE WANT TO GO TO THERE Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM To pages everywhere . -

Murmurs of a Girl in Me

Breaking the Silence Murmurs of the Girl in Me POWA VISION To create a safe society that does not tolerate violence against women, and where women are powerful, self-reliant, equal and respected. POWA MISSION To be a powerful, specialised and multi-skilled service provider that contributes towards the complete eradication of violence against women in society, in order to enhance women’s quality of life. POWA provides counselling, legal advice, court support and shelter to women survivors of domestic and sexual violence. POWA also engages in research, training, lobbying and advocacy. Contact POWA on: 011 642 4345 or visit our website: www.powa.co.za POWA Women’s Writing Competition 2007 Breaking the Silence Murmurs of the Girl in Me The CDP Trust Naledi Yamiso Arts and Culture Counsellor Training Project was born out of the CDP’s Tsogang Basadi Arts and Culture/Psychosocial Support Project for Women Survivors of Domestic Violence (2006-2008). The enormous impact of the interface between the creative arts processes and psychosocial support model on women’s lives, and the personal power fostered by the artworks and artifacts produced, led directly to the following: • An appreciation of the added value the CDP Trust model and methodology would bring to our sister organisations through the training of their counsellors. • An interactive training for transference model, based on our experience and activities in other projects that support the power of the visual narrative; making ‘the invisible visible’. • Equipping the counsellors with the knowledge required to advise on options and procedures for income- generating initiatives, opening up spaces and potential for economic liberation. -

A Thesis Entitled Me Want Food: a Discourse Analysis of 30 Rock By

A Thesis entitled Me Want Food: A Discourse Analysis of 30 Rock by JoAnna R. Murphy Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Sociology Dr. Mark Sherry, Committee Chair Dr. Patricia Case, Committee Member Dr. Barbara Coventry, Committee Member Dr. Patricia R. Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2011 Copyright 2011, JoAnna Ruth Murphy This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. ii An Abstract of Me Want Food: A Discourse Analysis of 30 Rock by JoAnna R. Murphy Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Sociology The University of Toledo December 2011 Using a combination of fat studies, the social construction of the body, Foucauldian approaches to the body, and cultural sociology, this thesis examines discourses about the fat female body in 30 Rock. The body is carnal and fleshy, but it is also socially constructed; this social construction has a long and deep cultural social history, and its power is particularly apparent with regard to the devaluation of the fat female body. By combining multiple theoretical approaches, a more nuanced and sophisticated understanding of discourses about the fat body emerges – suggesting that even when shows such as 30 Rock engage with counter-hegemonic discourses about the body such as fat acceptance, they may revert to hegemonic and heteronormative standards of beauty and the fat body. iii For my partner and husband Levi who supported me and grew with me during this time. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY Portrayal of African Americans in the Media

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature Portrayal of African Americans in the Media Master‟s Diploma Thesis Brno 2014 Supervisor: Author: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Bc. Lucie Pernicová Declaration I hereby declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ........................................................ Bc. Lucie Pernicová Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. for the patient guidance and valuable advice he provided me with during the writing of this thesis. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 5 2. Portrayal of African Americans in Films and on Television ..................................... 8 2.1. Stereotypical Images and Their Power .............................................................. 8 2.2. Basic Stereotypical Images of African Americans ............................................ 9 2.3. Stereotypical Film Portrayals of African Americans and the Arrival of the Talking Era .................................................................................................................. 12 2.4. Television Portrayals of African Americans .................................................... 14 2.4.1. The Increasing Importance of African American Viewers ....................... 17 2.4.2. Contemporary Images of African Americans .......................................... -

The Chinese People's Liberation Army at 75

THE LESSONS OF HISTORY: THE CHINESE PEOPLE’S LIBERATION ARMY AT 75 Edited by Laurie Burkitt Andrew Scobell Larry M. Wortzel July 2003 ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave., Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. Copies of this report may be obtained from the Publications Office by calling (717) 245-4133, FAX (717) 245-3820, or via the Internet at [email protected] ***** Most 1993, 1994, and all later Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. SSI’s Homepage address is: http:// www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/index.html ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail news- letter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also pro- vides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please let us know by e-mail at [email protected] or by calling (717) 245-3133. ISBN 1-58487-126-1 ii CONTENTS Foreword Ambassador James R. Lilley . v Part I: Overview. 1 1. Introduction: The Lesson Learned by China’s Soldiers Laurie Burkitt, Andrew Scobell, and Larry M. -

The Bull Market in Everything

Gun laws after Las Vegas Stand-off in Catalonia Goldman: vampire squid to damp squib Are women underpaid? OCTOBER 7TH–13TH 2017 Thebullmarket in everything Are asset prices too high? Going beyond reality. That’s innovation. Anticipating the future. Challenging the status quo. And always thinking one step ahead. At CaixaBank we have been thinking this way for over a hundred years. Continuously seeking to improve on reality. Providing our customers today with what they will need tomorrow. As a result we are recognised as one of the most innovative banks in the world. Contents The Economist October 7th 2017 5 9 The world this week Asia 41 Indonesian politics Leaders Jokowi at bay 13 Asset prices 42 Japan’s election The bull market in Mannequins cast no everything ballots 14 Guns in America 43 Radio in North Korea Deathly silence Making waves 14 Liberia 43 Economic policy in India The legacy of Ma Ellen Fifth columnists Las Vegas Do not despair, 16 Families and work 44 Immigration to Australia change is possible: leader, Having it all Almost one in three page14. The shooting has 18 Separatism in Catalonia 46 Banyan Homage to Formosa reinvigorated calls for gun On the cover How to save Spain control and highlighted its Prices are high across a limitations, page 27. range of assets. Is it time to Letters China Superstition helps explain worry? Leader, page13. Low why many Republicans think 20 On cancer, Syria, China, 47 Ageing in Hong Kong interest rates have made loose gun laws keep them safe: Brazil, corn, spies, free Wrangling over pensions more or less all investments Lexington, page 36 speech 48 Chiang Kai-shek expensive, page 23.