A Bitter Memory: Isaiah's Commission in Isaiah 6: 1-13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Canonical Function of Isaiah 13-14 A

Word & World Volume XIX, Number 2 Spring 1999 Serving Notice on Babylon: The Canonical Function of Isaiah 13-14 A. JOSEPH EVERSON California Lutheran University Thousand Oaks, California OR WELL OVER A GENERATION, THE PREMISE HAS BEEN WIDELY ACCEPTED THAT chapters 40-66 of the Isaiah scroll are a later expansion of earlier material found in Isaiah 1-39. This view is so prominent that the terms First Isaiah, Second Isaiah, and/or Third Isaiah are readily used in theological conversation, in seminary catalogs, course offerings, and in standard commentary and monograph titles. At no point in the scroll of Isaiah are the problems with these distinctions more apparent than in Isaiah 13-14. Here within the very heart of “First Isaiah,” we encounter poetry that is unambigu- ously addressed to Babylon, anticipating the downfall of that empire. How are we to understand the poetry in chapters 13-14? Do these chapters consist of small units which once had meaning in the eighth-century world?1 Were 1R. E. Clements, Isaiah 1-39 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980) 129-138, discerns five originally separate units within chapter 13; he contends that in three, Babylon was originally Yahweh’s instrument of destruction (13:2-3; 4-5; and 6-8). Only in the fifth originally separate unit (17-22) does Clements see the poem revised to be a word against Babylon. For an interpretation of the entire chapter against the eighth-century background, see J. R. Hayes and S. A. Irvine, Isaiah, the Eighth Century Prophet (Nashville: Abingdon, 1987). A. JOSEPH EVERSON is professor and chair of the department of religion at California Lutheran University. -

It Is Difficult to Speak About Jeremiah Without Comparing Him to Isaiah. It

751 It is diffi cult to speak about Jeremiah without comparing him to Isaiah. It might be wrong to center everything on the differences between their reactions to God’s call, namely, Isaiah’s enthusiasm (Is 6:8) as opposed to Jeremiah’s fear (Jer 1:6). It might have been only a question of their different temperaments. Their respec- tive vocation and mission should be complementary, both in terms of what refers to their lives and writings and to the infl uence that both of them were going to exercise among believers. Isaiah is the prophecy while Jeremiah is the prophet. The two faces of prophet- ism complement each other and they are both equally necessary to reorient history. Isaiah represents the message to which people will always need to refer in order to reaffi rm their faith. Jeremiah is the ever present example of the suffering of human beings when God bursts into their lives. There is no room, therefore, for a sentimental view of a young, peaceful and defenseless Jeremiah who suffered in silence from the wickedness of his persecu- tors. There were hints of violence in the prophet (11:20-23). In spite of the fact that he passed into history because of his own sufferings, Jeremiah was not always the victim of the calamities that he had announced. In his fi rst announcement, Jeremiah said that God had given him authority to uproot and to destroy, to build and to plant, specifying that the mission that had been entrusted to him encompassed not only his small country but “the nations.” The magnitude to such a task assigned to a man without credentials might surprise us; yet it is where the fi nger of God does appear. -

Micah at a Glance

Scholars Crossing The Owner's Manual File Theological Studies 11-2017 Article 33: Micah at a Glance Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Article 33: Micah at a Glance" (2017). The Owner's Manual File. 13. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Owner's Manual File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICAH AT A GLANCE This book records some bad news and good news as predicted by Micah. The bad news is the ten northern tribes of Israel would be captured by the Assyrians and the two southern tribes would suffer the same fate at the hands of the Babylonians. The good news foretold of the Messiah’s birth in Bethlehem and the ultimate establishment of the millennial kingdom of God. BOTTOM LINE INTRODUCTION QUESTION (ASKED 4 B.C.): WHERE IS HE THAT IS BORN KING OF THE JEWS? (MT. 2:2) ANSWER (GIVEN 740 B.C.): “BUT THOU, BETHLEHEM EPHRATAH, THOUGH THOU BE LITTLE AMONG THE THOUSANDS OF JUDAH, YET OUT OF THEE SHALL HE COME FORTH” (Micah 5:2). The author of this book, Micah, was a contemporary with Isaiah. Micah was a country preacher, while Isaiah was a court preacher. -

Unwelcome Words from the Lord: Isaiah's Messages

Word & World Volume XIX, Number 2 Spring 1999 Unwelcome Words from the Lord: Isaiah’s Messages ROLF A. JACOBSON Princeton Theological Seminary Princeton, New Jersey I. THE CUSTOM OF ASKING FOR PROPHETIC WORDS N BOTH ANCIENT ISRAEL AND THE NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES, IT WAS COMMON for prophets to be consulted prior to a momentous decision or event. Often, the king or a representative of the king would inquire of a prophet to find out whether the gods would bless a particular action which the king was considering. A. 1 Samuel 23. In the Old Testament, there are many examples of this phe- nomenon. 1 Sam 23:2-5 describes how David inquired of the Lord to learn whether he should attack the Philistines: Now they told David, “The Philistines are fighting against Keilah, and are rob- bing the threshing floors.” David inquired of the LORD, “Shall I go and attack these Philistines?” The LORD said to David, “Go and attack the Philistines and save Keilah.” But David’s men said to him, “Look, we are afraid here in Judah; how much more then if we go to Keilah against the armies of the Philistines?” Then David inquired of the LORD again. The LORD answered him, “Yes, go ROLF JACOBSON is a Ph.D. candidate in Old Testament at Princeton Theological Seminary. He is associate editor of the Princeton Seminary Bulletin and editorial assistant of Theology Today. Isaiah’s word of the Lord, even a positive word, often received an unwelcome re- ception. God’s promises, then and now, can be unwelcome because they warn against trusting any other promise. -

Exploring Zechariah, Volume 2

EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 VOLUME ZECHARIAH, EXPLORING is second volume of Mark J. Boda’s two-volume set on Zechariah showcases a series of studies tracing the impact of earlier Hebrew Bible traditions on various passages and sections of the book of Zechariah, including 1:7–6:15; 1:1–6 and 7:1–8:23; and 9:1–14:21. e collection of these slightly revised previously published essays leads readers along the argument that Boda has been developing over the past decade. EXPLORING MARK J. BODA is Professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is the author of ten books, including e Book of Zechariah ZECHARIAH, (Eerdmans) and Haggai and Zechariah Research: A Bibliographic Survey (Deo), and editor of seventeen volumes. VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Boda Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-201-0) available at http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com Mark J. Boda Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 ANCIENT NEAR EAST MONOGRAPHS Editors Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach C. L. Crouch Esther J. Hamori Chistopher B. Hays René Krüger Graciela Gestoso Singer Bruce Wells Number 17 EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah by Mark J. -

Do the Prophets Teach That Babylonia Will Be Rebuilt in the Eschaton

Scholars Crossing LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations 1998 Do the Prophets Teach That Babylonia Will Be Rebuilt in the Eschaton Homer Heater Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Heater, Homer, "Do the Prophets Teach That Babylonia Will Be Rebuilt in the Eschaton" (1998). LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations. 281. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/281 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JETS 41/1 (March 1998) 23-43 DO THE PROPHETS TEACH THAT BABYLONIA WILL BE REBUILT IN THE ESCHATON? HOMER HEATER, JR.* Dispensationalists have traditionally argued that "Babylon" in Revela tion 14 and chaps. 17-18 is a symbol indicating some form of reestablished Rome. * In recent days a renewed interest has been shown in the idea that the ancient empire of Babylonia and city of Babylon will be rebuilt.2 This conclusion comes from a reading of the prophets—Isaiah and Jeremiah -

5. Jesus Christ-The Key of David (Isaiah 22:15-25)

1 Jesus Christ, the Key of David Isaiah 22:15-25 Introduction: In Isaiah 22, the Lord sent Isaiah to make an announcement to a government official named Shebna, who served Hezekiah, the king of Judah. The news he had for Shebna was not good. Shebna had, apparently, used his position to increase his own wealth and glory, and had usurped authority which did not belong to him. Shebna received the news that he would soon be abruptly removed from his office. Isaiah also announced that another man (named Eliakim) would take his place, who would administer the office faithfully. This new man would be a type of Jesus Christ. Isaiah 22:15-25 I. The fall of self-serving Shebna (vv. 15-19) In verse 15, the Lord sent Isaiah to deliver a message to Shebna, who was the treasurer in the government of Judah. He is also described as being “over the house.” This particular position was first mentioned in the time of Solomon. (Apparently, the office did not exist in the days of King Saul or King David, because it is not mentioned.) Afterward, it became an important office both in the northern and southern kingdoms. 1 Kings 4:1-6; 16:9; 18:3 2 Kings 10:5 The office of the man who was “over the house” of the king of Judah seems to have increased in importance over time, until it was similar to the Egyptian office of vizier. Joseph had been given this incredibly powerful position in the government of Pharaoh. (In fact, this position seems to have been created, for the first time, in Joseph’s day.) Joseph possessed all the power of the Pharaoh. -

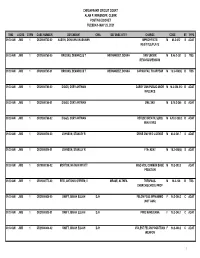

Chesapeake Circuit Court Alan P. Krasnoff, Clerk Posting Docket Tuesday- May 25, 2021

CHESAPEAKE CIRCUIT COURT ALAN P. KRASNOFF, CLERK POSTING DOCKET TUESDAY- MAY 25, 2021 TIME JUDGE CTRM CASE NUMBER DEFENDANT CWA DEFENSE ATTY CHARGE CODE ST TYPE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000762-00 AUSTIN, DONIVAN VAUSHAWN IMPROP/FICTS M 46.2-612 S ADAT REG/TITLE/PLATE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000765-00 BROOKS, DEMARCUS T HERNANDEZ, DONNA DRIV UNDER M B.46.2-301 S TBS REVO/SUSPENSION 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000765-01 BROOKS, DEMARCUS T HERNANDEZ, DONNA CAPIAS FAIL TO APPEAR M 18.2-456(6) B TBS 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-00 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN CARRY GUN PUBLIC-UNDR M 18.2-308.012 B ADAT INFLUNCE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-01 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN DWI, 2ND M B.18.2-266 B ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-02 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN REFUSE BREATH, SUBQ M A.18.2-268.3 B ADAT W/IN 10YRS 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000514-00 JOHNSON, STANLEY R DRIVE CMV W/O LICENSE M 46.2-341.7 S ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000514-01 JOHNSON, STANLEY R FTA- ADAT M 18.2-456(6) S ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR19000796-02 MORTON, NATHAN WYATT MISD VIOL COMMUN BASE M 19.2-303.3 ADAT PRBATION 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000773-00 REID, ANTONIO O'BRIEN; II MEASE, ALTHEA TRESPASS- M 18.2-128 B TBS CHURCH/SCHOOL PROP 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-00 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH FELON POSS WPN/AMMO F 18.2-308.2 C ADAT (NOT GUN) 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-01 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH PWID MARIJUANA F 18.2-248.1 C ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-02 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH VIOLENT FELON POSS/TRAN F 18.2-308.2 C ADAT WEAPON 1 CHESAPEAKE CIRCUIT COURT ALAN P. -

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons SONG OF SOLOMON JEREMIAH NEWEST ADDITIONS: Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 53 (Isaiah 52:13-53:12) - Bruce Hurt Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 35 - Bruce Hurt ISAIAH RESOURCES Commentaries, Sermons, Illustrations, Devotionals Click chart to enlarge Click chart to enlarge Chart from recommended resource Jensen's Survey of the OT - used by permission Another Isaiah Chart see on right side Caveat: Some of the commentaries below have "jettisoned" a literal approach to the interpretation of Scripture and have "replaced" Israel with the Church, effectively taking God's promises given to the literal nation of Israel and "transferring" them to the Church. Be a Berean Acts 17:11-note! ISAIAH ("Jehovah is Salvation") See Excellent Timeline for Isaiah - page 39 JEHOVAH'S JEHOVAH'S Judgment & Character Comfort & Redemption (Isaiah 1-39) (Isaiah 40-66) Uzziah Hezekiah's True Suffering Reigning Jotham Salvation & God Messiah Lord Ahaz Blessing 1-12 13-27 28-35 36-39 40-48 49-57 58-66 Prophecies Prophecies Warnings Historical Redemption Redemption Redemption Regarding Against & Promises Section Promised: Provided: Realized: Judah & the Nations Israel's Israel's Israel's Jerusalem Deliverance Deliverer Glorious Is 1:1-12:6 Future Prophetic Historic Messianic Holiness, Righteousness & Justice of Jehovah Grace, Compassion & Glory of Jehovah God's Government God's Grace "A throne" Is 6:1 "A Lamb" Is 53:7 Time 740-680BC OTHER BOOK CHARTS ON ISAIAH Interesting Facts About Isaiah Isaiah Chart The Book of Isaiah Isaiah Overview Chart by Charles Swindoll Visual Overview Introduction to Isaiah by Dr John MacArthur: Title, Author, Date, Background, Setting, Historical, Theological Themes, Interpretive Challenges, Outline by Chapter/Verse. -

Workbook on Isaiah

Isaiah Condemnation And Comfort “Now it shall come to pass in the latter days that the mountain of the Lord’s house shall be established on the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hills; and all nations shall flow to it. Many people shall come and say, ‘Come, and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, to the house of the God of Jacob; He will teach us His ways, and we shall walk in His paths.’ For out of Zion shall go forth the law, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.” (Isaiah 2:2–3) © 2005 David Padfield • All Rights Reserved www.padfield.com Isaiah Part One: Prophecies of Condemnation (1:1—35:10) I. Prophecies Against Judah (1:1—12:6) A. The Judgment of Judah (1:1–31) 1. How does Isaiah describe the nation of Israel? 2. What did the Lord promise to the people if they would repent? B. The Day of the Lord (2:1—4:6) 1. What are the “latter days” mentioned in Isaiah 2:2? 2. What was to go forth from Jerusalem? When? 3. How and when would men “beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks”? 4. How would the Lord “come upon everything proud and lofty”? 5. According to chapter three, what did the Lord have in store for Jerusalem? 6. How would the Lord punish the “daughters of Zion”? The Book Of Isaiah David Padfield www.padfield.com 1 7. What is the “Branch of the Lord”? 8. -

Jumalan Kasvot Suomeksi. Metaforisaatio Ja Erään

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 82 Maria Kela Jumalan kasvot suomeksi Metaforisaatio ja erään uskonnollisen ilmauksen synty JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 82 Maria Kela Jumalan kasvot suomeksi Metaforisaatio ja erään uskonnollisen ilmauksen synty Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa joulukuun 15. päivänä 2007 kello 12. JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Jumalan kasvot suomeksi Metaforisaatio ja erään uskonnollisen ilmauksen synty JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 82 Maria Kela Jumalan kasvot suomeksi Metaforisaatio ja erään uskonnollisen ilmauksen synty JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Aila Mielikäinen Department of Languages Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä Cover picture by Jyrki Kela URN:ISBN:9789513930691 ISBN 978-951-39-3069-1 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-3008-0 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Kela, Maria God’s face in Finnish. Metaphorisation and the emergence of a religious expression. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2007, 275 p. (Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities ISSN 1459-4331; 82) ISBN 978-951-39-3069-1 (PDF), 978-951-39-3008-0 (nid.) English summary Diss. The objective of this study is to reveal, how a religious expression is emerged through the process of metaphorisation in translated biblical language. -

YHVH's Servant

YHVH’s Servant A Literary Analysis of Isaiah YHVH’s Servant • If we want to understand and correctly interpret the book of Isaiah in its proper context, we need to understand much of its literary structure. • The Literary Structure of the Old Testament A Commentary on Genesis - Malachi is the main source for the literary structure of Isaiah in this presentation. 2 YHVH’s Servant • I have made a few modifications to the chiasms from this book, as I have seen fit, for this presentation. • However, most of the summary structures are intact. 3 YHVH’s Servant • Isaiah is really a chiasm composed of multiple layers of chiasms and numerous parallels or couplets that can cause the average reader to get lost in a fog. • There are at least 3 and sometimes 4 levels of chiasms in Isaiah, which contribute to this fog. 4 YHVH’s Servant In this presentation, we will: 1 Look at the overall structure of Isaiah; 2 Look the secondary and some tertiary chiasms in Isaiah; 3 Focus our attention on the portions related to YHVH’s servants to properly identify the servants of YHVH in Isaiah. 5 1 YHVH’s Servant • The following chiasm contains a broad overview of the entire book of Isaiah. • It is the primary chiasm for Isaiah. 6 1 YHVH’s Servant The Book of Isaiah A1 Message of condemnation, pleading, and future restoration (1:1-12:6). B1 Oracles to nations: Humiliation of proud king of Babylon (13:1-27:13). C1 Collection of woes: Don’t trust in earthly powers (28:1-35:10).