UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It Is Difficult to Speak About Jeremiah Without Comparing Him to Isaiah. It

751 It is diffi cult to speak about Jeremiah without comparing him to Isaiah. It might be wrong to center everything on the differences between their reactions to God’s call, namely, Isaiah’s enthusiasm (Is 6:8) as opposed to Jeremiah’s fear (Jer 1:6). It might have been only a question of their different temperaments. Their respec- tive vocation and mission should be complementary, both in terms of what refers to their lives and writings and to the infl uence that both of them were going to exercise among believers. Isaiah is the prophecy while Jeremiah is the prophet. The two faces of prophet- ism complement each other and they are both equally necessary to reorient history. Isaiah represents the message to which people will always need to refer in order to reaffi rm their faith. Jeremiah is the ever present example of the suffering of human beings when God bursts into their lives. There is no room, therefore, for a sentimental view of a young, peaceful and defenseless Jeremiah who suffered in silence from the wickedness of his persecu- tors. There were hints of violence in the prophet (11:20-23). In spite of the fact that he passed into history because of his own sufferings, Jeremiah was not always the victim of the calamities that he had announced. In his fi rst announcement, Jeremiah said that God had given him authority to uproot and to destroy, to build and to plant, specifying that the mission that had been entrusted to him encompassed not only his small country but “the nations.” The magnitude to such a task assigned to a man without credentials might surprise us; yet it is where the fi nger of God does appear. -

Micah at a Glance

Scholars Crossing The Owner's Manual File Theological Studies 11-2017 Article 33: Micah at a Glance Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Article 33: Micah at a Glance" (2017). The Owner's Manual File. 13. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Owner's Manual File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICAH AT A GLANCE This book records some bad news and good news as predicted by Micah. The bad news is the ten northern tribes of Israel would be captured by the Assyrians and the two southern tribes would suffer the same fate at the hands of the Babylonians. The good news foretold of the Messiah’s birth in Bethlehem and the ultimate establishment of the millennial kingdom of God. BOTTOM LINE INTRODUCTION QUESTION (ASKED 4 B.C.): WHERE IS HE THAT IS BORN KING OF THE JEWS? (MT. 2:2) ANSWER (GIVEN 740 B.C.): “BUT THOU, BETHLEHEM EPHRATAH, THOUGH THOU BE LITTLE AMONG THE THOUSANDS OF JUDAH, YET OUT OF THEE SHALL HE COME FORTH” (Micah 5:2). The author of this book, Micah, was a contemporary with Isaiah. Micah was a country preacher, while Isaiah was a court preacher. -

Unwelcome Words from the Lord: Isaiah's Messages

Word & World Volume XIX, Number 2 Spring 1999 Unwelcome Words from the Lord: Isaiah’s Messages ROLF A. JACOBSON Princeton Theological Seminary Princeton, New Jersey I. THE CUSTOM OF ASKING FOR PROPHETIC WORDS N BOTH ANCIENT ISRAEL AND THE NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES, IT WAS COMMON for prophets to be consulted prior to a momentous decision or event. Often, the king or a representative of the king would inquire of a prophet to find out whether the gods would bless a particular action which the king was considering. A. 1 Samuel 23. In the Old Testament, there are many examples of this phe- nomenon. 1 Sam 23:2-5 describes how David inquired of the Lord to learn whether he should attack the Philistines: Now they told David, “The Philistines are fighting against Keilah, and are rob- bing the threshing floors.” David inquired of the LORD, “Shall I go and attack these Philistines?” The LORD said to David, “Go and attack the Philistines and save Keilah.” But David’s men said to him, “Look, we are afraid here in Judah; how much more then if we go to Keilah against the armies of the Philistines?” Then David inquired of the LORD again. The LORD answered him, “Yes, go ROLF JACOBSON is a Ph.D. candidate in Old Testament at Princeton Theological Seminary. He is associate editor of the Princeton Seminary Bulletin and editorial assistant of Theology Today. Isaiah’s word of the Lord, even a positive word, often received an unwelcome re- ception. God’s promises, then and now, can be unwelcome because they warn against trusting any other promise. -

Exploring Zechariah, Volume 2

EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 VOLUME ZECHARIAH, EXPLORING is second volume of Mark J. Boda’s two-volume set on Zechariah showcases a series of studies tracing the impact of earlier Hebrew Bible traditions on various passages and sections of the book of Zechariah, including 1:7–6:15; 1:1–6 and 7:1–8:23; and 9:1–14:21. e collection of these slightly revised previously published essays leads readers along the argument that Boda has been developing over the past decade. EXPLORING MARK J. BODA is Professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is the author of ten books, including e Book of Zechariah ZECHARIAH, (Eerdmans) and Haggai and Zechariah Research: A Bibliographic Survey (Deo), and editor of seventeen volumes. VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Boda Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-201-0) available at http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com Mark J. Boda Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 ANCIENT NEAR EAST MONOGRAPHS Editors Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach C. L. Crouch Esther J. Hamori Chistopher B. Hays René Krüger Graciela Gestoso Singer Bruce Wells Number 17 EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah by Mark J. -

5. Jesus Christ-The Key of David (Isaiah 22:15-25)

1 Jesus Christ, the Key of David Isaiah 22:15-25 Introduction: In Isaiah 22, the Lord sent Isaiah to make an announcement to a government official named Shebna, who served Hezekiah, the king of Judah. The news he had for Shebna was not good. Shebna had, apparently, used his position to increase his own wealth and glory, and had usurped authority which did not belong to him. Shebna received the news that he would soon be abruptly removed from his office. Isaiah also announced that another man (named Eliakim) would take his place, who would administer the office faithfully. This new man would be a type of Jesus Christ. Isaiah 22:15-25 I. The fall of self-serving Shebna (vv. 15-19) In verse 15, the Lord sent Isaiah to deliver a message to Shebna, who was the treasurer in the government of Judah. He is also described as being “over the house.” This particular position was first mentioned in the time of Solomon. (Apparently, the office did not exist in the days of King Saul or King David, because it is not mentioned.) Afterward, it became an important office both in the northern and southern kingdoms. 1 Kings 4:1-6; 16:9; 18:3 2 Kings 10:5 The office of the man who was “over the house” of the king of Judah seems to have increased in importance over time, until it was similar to the Egyptian office of vizier. Joseph had been given this incredibly powerful position in the government of Pharaoh. (In fact, this position seems to have been created, for the first time, in Joseph’s day.) Joseph possessed all the power of the Pharaoh. -

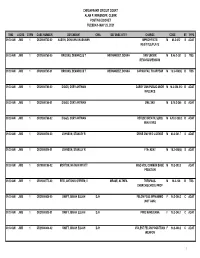

Chesapeake Circuit Court Alan P. Krasnoff, Clerk Posting Docket Tuesday- May 25, 2021

CHESAPEAKE CIRCUIT COURT ALAN P. KRASNOFF, CLERK POSTING DOCKET TUESDAY- MAY 25, 2021 TIME JUDGE CTRM CASE NUMBER DEFENDANT CWA DEFENSE ATTY CHARGE CODE ST TYPE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000762-00 AUSTIN, DONIVAN VAUSHAWN IMPROP/FICTS M 46.2-612 S ADAT REG/TITLE/PLATE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000765-00 BROOKS, DEMARCUS T HERNANDEZ, DONNA DRIV UNDER M B.46.2-301 S TBS REVO/SUSPENSION 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000765-01 BROOKS, DEMARCUS T HERNANDEZ, DONNA CAPIAS FAIL TO APPEAR M 18.2-456(6) B TBS 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-00 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN CARRY GUN PUBLIC-UNDR M 18.2-308.012 B ADAT INFLUNCE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-01 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN DWI, 2ND M B.18.2-266 B ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-02 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN REFUSE BREATH, SUBQ M A.18.2-268.3 B ADAT W/IN 10YRS 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000514-00 JOHNSON, STANLEY R DRIVE CMV W/O LICENSE M 46.2-341.7 S ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000514-01 JOHNSON, STANLEY R FTA- ADAT M 18.2-456(6) S ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR19000796-02 MORTON, NATHAN WYATT MISD VIOL COMMUN BASE M 19.2-303.3 ADAT PRBATION 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000773-00 REID, ANTONIO O'BRIEN; II MEASE, ALTHEA TRESPASS- M 18.2-128 B TBS CHURCH/SCHOOL PROP 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-00 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH FELON POSS WPN/AMMO F 18.2-308.2 C ADAT (NOT GUN) 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-01 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH PWID MARIJUANA F 18.2-248.1 C ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-02 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH VIOLENT FELON POSS/TRAN F 18.2-308.2 C ADAT WEAPON 1 CHESAPEAKE CIRCUIT COURT ALAN P. -

Workbook on Isaiah

Isaiah Condemnation And Comfort “Now it shall come to pass in the latter days that the mountain of the Lord’s house shall be established on the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hills; and all nations shall flow to it. Many people shall come and say, ‘Come, and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, to the house of the God of Jacob; He will teach us His ways, and we shall walk in His paths.’ For out of Zion shall go forth the law, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.” (Isaiah 2:2–3) © 2005 David Padfield • All Rights Reserved www.padfield.com Isaiah Part One: Prophecies of Condemnation (1:1—35:10) I. Prophecies Against Judah (1:1—12:6) A. The Judgment of Judah (1:1–31) 1. How does Isaiah describe the nation of Israel? 2. What did the Lord promise to the people if they would repent? B. The Day of the Lord (2:1—4:6) 1. What are the “latter days” mentioned in Isaiah 2:2? 2. What was to go forth from Jerusalem? When? 3. How and when would men “beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks”? 4. How would the Lord “come upon everything proud and lofty”? 5. According to chapter three, what did the Lord have in store for Jerusalem? 6. How would the Lord punish the “daughters of Zion”? The Book Of Isaiah David Padfield www.padfield.com 1 7. What is the “Branch of the Lord”? 8. -

References to the Messiah in the Pentateuch, Isaiah and Daniel: a Zimbabwean Perspective

Annals of Global History Volume 1, Issue 2, 2019, PP 12-16 ISSN 2642-8172 References to the Messiah in the Pentateuch, Isaiah and Daniel: A Zimbabwean Perspective Menard Musendekwa* Research Fellow, Department of Biblical Studies, Stellenbosch University, South Africa *Corresponding Author: Menard Musendekwa, Research Fellow Department of Biblical Studies, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Are there messianic expectations or messianic characters in the Pentateuch, Isaiah and Daniel? This research will examine if there can be messianic expectations in the Pentateuch linked to the priest in circumstances that do not presuppose an obvious crisis. The role played by an “anointed” priest in the Pentateuch seems to come about as the perpetrators of sin sought atonement (Lev. 4:3, 5, 16; 6:22 6:15). Are the priests intervening as “anointed” one due to indirect crisis by sin? This research will examine as to whether reference to “messiah” in Isaiah 9: 44:28-45:1-8 and Daniel 9:25-27 come about as a response to social, economic, political and religious crises that emanated from the failure of Israel to uphold Yahweh’s instruction. If that be so these findings may help to examine why Mugabe had gained messianic characterization during the past decade. The researcher as a citizen of Zimbabwe queries if such characterization emanate from his involvement in the liberation struggle or dependence on scriptures as trusted source for rhetorical propaganda to legitimize his role in a bid to legitimize his authority while the country was experiencing e socio-economic crises. INTRODUCTION emanating from dependency on biblical principles of hope to restore the lost support. -

What You Need to Know About the Book of Jonah

Scholars Crossing Willmington School of the Bible 2009 What You Need to Know About the Book of Jonah Harold L. Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/will_know Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold L., "What You Need to Know About the Book of Jonah" (2009). 56. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/will_know/56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Willmington School of the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE BOOK OF JONAH BOTTOM LINE INTRODUCTION THIS BOOK CONTAINS THE BIGGEST FISH STORY OF ALL TIME. BUT IT ISN’T WHAT YOU THINK IT IS. Almost everyone has heard the story of the huge sea creature that swallowed Jonah, and about Jonah’s pitiful prayer for deliverance while inside its stomach (ch. 1-2). But the real fish story takes place in chapter 3. To understand this, consider an event that would transpire some seven centuries later in northern Israel: “And Jesus, walking by the sea of Galilee, saw two brethren, Simon called Peter, and Andrew his brother, casting a net into the sea: for they were fishers. And he saith unto them, Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men. And they straightway left their nets, and followed him” (Mt. 4:18-20). In this passage Jesus taught that the “fish” God is looking to catch are sinful men, and the real “fishermen” are soul winners. -

The Jesse Tree Who Was Jesse?

THE JESSE TREE WHO WAS JESSE? The prophet Isaiah foretold the coming of the Messiah. Isaiah's words helped people L- know that the One who was promised to them by God would be born into the family of Jesse. " A shoot shall sprout from the stump of Jesse and from his roots a bud shall blossom." Isaiah II: I-10 Jesse of Bethlehem had seven sons. Jesse's youngest son, David, watched over the sheep for him. One day the prophet Samuel came to Jesse's house and met David. Samuel anointed David. Many years later, David became King. It was from Jesse that the family tree branched out to David and his descendants. Jesse and David were ancestors of Jesus. At the time of Jesus' birth all those who belonged to the family of David had to return to the town of Bethlehem because a census was being taken. Since Joseph and Mary were of the House of David, they had to travel from Nazareth to Bethlehem to register. WHAT IS THE JESSE TREE? The Jesse Tree is a special tree used during the season of Advent. The Jesse Tree represents the family tree of Jesus. It serves as a reminder of the human family of Jesus. The uniqueness of the Jesse Tree comes from the ornaments that are used to decorate it. They are symbols that depict the ancestors of Jesus or a prophecy fulfilled at His coming. Traditionally, the Jesse Tree ornaments also included representations of Adam, F.ve and Creation. These symbolize the promise.. The Jesse Tree Book SUGGESTIONS FOR JESSE TREE ORNAMENTS Directions: The list of names below are Sarah: Genesis 15 and 21 suggestions that can be used for Jesse Tree Ornaments. -

Micah 6:1-8 the Prophet Micah Lived at the Same Time As the Prophet

Micah 6:1-8 The Prophet Micah lived at the same time as the Prophet Isaiah, but they served the LORD in different ways. While Isaiah concentrated his preaching in the Southern Kingdom - Judah and its capital city, Jerusalem - Micah preached to both the northern and southern kingdoms. The message of these two prophets was different too. Isaiah spoke cheerful words like, “Shout for joy, O heavens; rejoice O earth; burst into song, O mountains! For the LORD comforts His people, and will have compassion on His afflicted ones.” But Micah’s prophecies are more ominous. For example, in his prophecy today, the mountains are called upon not to burst into joyful song, but to serve as jury members. You see, the LORD’s patience was quickly running out, especially for the Northern Kingdom. In less than 10 years, they would cease to exist as a nation! Social sins, religious corruption, and spiritual laxity in general, had run rampant among God’s people for too long. So, in our text for today, the LORD brings A Case Against His People. As we investigate this ancient court case, let’s take note especially of the prosecution of the LORD, and the defense of His people. Before we get to the main event, let’s set the scene. As is the case in an impeachment trial - where the members of the United States Senate serve as members of the jury - the LORD had gathered some very prominent jurors for this case too. He designated the hills and mountains to serve in this capacity, probably because of the tremendous experience they had in keeping with their great age. -

The Remnant Concept As Defined by Amos

[This paper has been reformulated from old, unformatted electronic files and may not be identical to the edited version that appeared in print. The original pagination has been maintained, despite the resulting odd page breaks, for ease of scholarly citation. However, scholars quoting this article should use the print version or give the URL.] Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 7/2 (Autumn 1996): 67-81. Article copyright © 1996 by Ganoune Diop. The Remnant Concept as Defined by Amos Ganoune Diop Institut Adventiste du Saleve France Introduction The study of the remnant concept from a linguistic perspective has revealed that this theme in Hebrew is basically represented by several derivatives of six different roots.1 Five of them are used in the eighth century B.C. prophetic writ- ings. The purpose of this article is to investigate the earliest prophetic writing, the book of Amos, in order to understand not only what is meant when the term “remnant” is used but also the reason for its use. We will try to answer the fol- lowing questions: What was the prophet Amos saying when he used this desig- nation (whether by itself or in association with patriarchal figures)? What are the characteristics of such an entity? What is the theological intention of the prophet? We have chosen this era because the eighth century prophets (Amos, Hosea, Isaiah, Micah) were messengers to God’s people at a crucial time in their his- tory. All of them were sent to announce a message of judgment. Without a doubt the eighth century was “the time of the end” for the northern nation of Israel.