Once Again the Term Maśśā' in Zechariah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messianic Prophecies Fulfilled by Yeshua (Jesus)

Messianic Prophecies Fulfilled by Yeshua (Jesus) What is a Messianic Prophecy? Messianic prophecy is phenomenal evidence that sets the Bible apart from the other "holy books." We strongly encourage you to read the Old Testament prophecies and the New Testament fulfillment’s. Better yet, get a Jewish Tanakh (the Hebrew scripture read in the Jewish synagogues) and read the Messianic prophecies from there. It is dramatic, eye- opening and potentially life-changing The noun prophecy describes a “prediction of the future, made under divine inspiration” or a “revelation of God.” The act of making a prophecy is the verb,prophesy. Of the prophecies written in the Bible about events that were to have taken place by now, every one was fulfilled with 100% accuracy. This is a statement that can not be truthfully made about any other “sacred writing.” This is important because the Bible says God will give us a savior who provides a way for us to go to heaven. If the prophecies are 100% accurate, we know it is going to happen. Messianic Prophecy: Fulfillment by Yeshua (Jesus) Messianic prophecy was fulfilled by the Messiah, Yeshua (Jesus) the Christ. Although many Jews did not accept Yeshua (Jesus) as their Messiah, many did, based in dramatic part on the fulfillment of historical prophecies, spread rapidly throughout the Roman Empire of the 1st Century. Examine the prophecies yourself, and calculate the probability of one man fulfilling just a handful of the most specific ones, and you’ll be amazed. “Yeshua (Jesus) said to them, “These are the words which I spoke to you while I was still with you, that all things must be fulfilled which were written in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms concerning Me.” Luke 24:44 What is a “Messianic” Prophecy? Messianic prophecy is the collection of over 300 prophesies with over 100 predictions that could only be fulfilled by Yeshua (Jesus) (a conservative estimate) in the Old Testament about the future Messiah of the Jewish people. -

It Is Difficult to Speak About Jeremiah Without Comparing Him to Isaiah. It

751 It is diffi cult to speak about Jeremiah without comparing him to Isaiah. It might be wrong to center everything on the differences between their reactions to God’s call, namely, Isaiah’s enthusiasm (Is 6:8) as opposed to Jeremiah’s fear (Jer 1:6). It might have been only a question of their different temperaments. Their respec- tive vocation and mission should be complementary, both in terms of what refers to their lives and writings and to the infl uence that both of them were going to exercise among believers. Isaiah is the prophecy while Jeremiah is the prophet. The two faces of prophet- ism complement each other and they are both equally necessary to reorient history. Isaiah represents the message to which people will always need to refer in order to reaffi rm their faith. Jeremiah is the ever present example of the suffering of human beings when God bursts into their lives. There is no room, therefore, for a sentimental view of a young, peaceful and defenseless Jeremiah who suffered in silence from the wickedness of his persecu- tors. There were hints of violence in the prophet (11:20-23). In spite of the fact that he passed into history because of his own sufferings, Jeremiah was not always the victim of the calamities that he had announced. In his fi rst announcement, Jeremiah said that God had given him authority to uproot and to destroy, to build and to plant, specifying that the mission that had been entrusted to him encompassed not only his small country but “the nations.” The magnitude to such a task assigned to a man without credentials might surprise us; yet it is where the fi nger of God does appear. -

SAINT MICHAEL the ARCHANGEL CATHOLIC CHURCH

ARCHDIOCESE OF GALVESTON-HOUSTON SAINT MICHAEL the ARCHANGEL CATHOLIC CHURCH JULY 11, 2021 | FIFTEENTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Jesus summoned the Twelve and began to send them out two by two and gave them authority over unclean spirits. Mark 6:7 1801 SAGE ROAD, HOUSTON, TEXAS 77056 | (713) 621-4370 | STMICHAELCHURCH.NET ST. MICHAEL THE ARCHANGEL CATHOLIC CHURCH The Gospel This week’s Gospel and the one for next week describe how Jesus sent the disciples to minister in his name and the disciples’ return to Jesus afterward. These two passages, however, are not presented together in Mark’s Gospel. Inserted between the two is the report of Herod’s fears that Jesus is John the Baptist back from the dead. In Mark’s Gospel, Jesus’ ministry is presented in connection with the teaching of John the Baptist. Jesus’ public ministry begins after John is arrested. John the Baptist prepared the way for Jesus, who preached the fulfillment of the Kingdom of God. While we do not read these details about John the Baptist in our Gospel this week or next week, our Lectionary sequence stays consistent with Mark’s theme. Recall that last week we heard how Jesus was rejected in his hometown of Nazareth. The insertion of the reminder about John the Baptist’s ministry and his death at the hands of Herod in Mark’s Gospel makes a similar point. Mark reminds his readers about this dangerous context for Jesus’ ministry and that of his disciples. Preaching repentance and the Kingdom of God is dangerous business for Jesus and for his disciples. -

Zechariah 9–14 and the Continuation of Zechariah During the Ptolemaic Period

Journal of Hebrew Scriptures Volume 13, Article 9 DOI:10.5508/jhs.2013.v13.a9 Zechariah 9–14 and the Continuation of Zechariah during the Ptolemaic Period HERVÉ GONZALEZ Articles in JHS are being indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, RAMBI, and BiBIL. Their abstracts appear in Religious and Theological Abstracts. The journal is archived by Library and Archives Canada and is accessible for consultation and research at the Electronic Collection site maintained by Library and Archives Canada. ISSN 1203L1542 http://www.jhsonline.org and http://purl.org/jhs ZECHARIAH 9–14 AND THE CONTINUATION OF ZECHARIAH DURING THE PTOLEMAIC PERIOD HERVÉ GONZALEZ UNIVERSITY OF LAUSANNE INTRODUCTION This article seeks to identify the sociohistorical factors that led to the addition of chs. 9–14 to the book of Zechariah.1 It accepts the classical scholarly hypothesis that Zech 1–8 and Zech 9–14 are of different origins and Zech 9–14 is the latest section of the book.2 Despite a significant consensus on this !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1 The article presents the preliminary results of a larger work currently underway at the University of Lausanne regarding war in Zech 9–14. I am grateful to my colleagues Julia Rhyder and Jan Rückl for their helpful comments on previous versions of this article. 2 Scholars usually assume that Zech 1–8 was complete when chs. 9–14 were added to the book of Zechariah, and I will assume the sameT see for instance E. Bosshard and R. G. Kratz, “Maleachi im Zwölfprophetenbuch,” BN 52 (1990), 27–46 (41–45)T O. H. -

Micah at a Glance

Scholars Crossing The Owner's Manual File Theological Studies 11-2017 Article 33: Micah at a Glance Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Article 33: Micah at a Glance" (2017). The Owner's Manual File. 13. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Owner's Manual File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICAH AT A GLANCE This book records some bad news and good news as predicted by Micah. The bad news is the ten northern tribes of Israel would be captured by the Assyrians and the two southern tribes would suffer the same fate at the hands of the Babylonians. The good news foretold of the Messiah’s birth in Bethlehem and the ultimate establishment of the millennial kingdom of God. BOTTOM LINE INTRODUCTION QUESTION (ASKED 4 B.C.): WHERE IS HE THAT IS BORN KING OF THE JEWS? (MT. 2:2) ANSWER (GIVEN 740 B.C.): “BUT THOU, BETHLEHEM EPHRATAH, THOUGH THOU BE LITTLE AMONG THE THOUSANDS OF JUDAH, YET OUT OF THEE SHALL HE COME FORTH” (Micah 5:2). The author of this book, Micah, was a contemporary with Isaiah. Micah was a country preacher, while Isaiah was a court preacher. -

Unwelcome Words from the Lord: Isaiah's Messages

Word & World Volume XIX, Number 2 Spring 1999 Unwelcome Words from the Lord: Isaiah’s Messages ROLF A. JACOBSON Princeton Theological Seminary Princeton, New Jersey I. THE CUSTOM OF ASKING FOR PROPHETIC WORDS N BOTH ANCIENT ISRAEL AND THE NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES, IT WAS COMMON for prophets to be consulted prior to a momentous decision or event. Often, the king or a representative of the king would inquire of a prophet to find out whether the gods would bless a particular action which the king was considering. A. 1 Samuel 23. In the Old Testament, there are many examples of this phe- nomenon. 1 Sam 23:2-5 describes how David inquired of the Lord to learn whether he should attack the Philistines: Now they told David, “The Philistines are fighting against Keilah, and are rob- bing the threshing floors.” David inquired of the LORD, “Shall I go and attack these Philistines?” The LORD said to David, “Go and attack the Philistines and save Keilah.” But David’s men said to him, “Look, we are afraid here in Judah; how much more then if we go to Keilah against the armies of the Philistines?” Then David inquired of the LORD again. The LORD answered him, “Yes, go ROLF JACOBSON is a Ph.D. candidate in Old Testament at Princeton Theological Seminary. He is associate editor of the Princeton Seminary Bulletin and editorial assistant of Theology Today. Isaiah’s word of the Lord, even a positive word, often received an unwelcome re- ception. God’s promises, then and now, can be unwelcome because they warn against trusting any other promise. -

Notes on Amos 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Amos 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE AND WRITER The title of the book comes from its writer. The prophet's name means "burden-bearer" or "load-carrier." Of all the 16 Old Testament writing prophets, only Amos recorded what his occupation was before God called him to become a prophet. Amos was a "sheepherder" (Heb. noqed; cf. 2 Kings 3:4) or "sheep breeder," and he described himself as a "herdsman" (Heb. boqer; 7:14). He was more than a shepherd (Heb. ro'ah), though some scholars deny this.1 He evidently owned or managed large herds of sheep, and or goats, and was probably in charge of shepherds. Amos also described himself as a "grower of sycamore figs" (7:14). Sycamore fig trees are not true fig trees, but a variety of the mulberry family, which produces fig-like fruit. Each fruit had to be scratched or pierced to let the juice flow out so the "fig" could ripen. These trees grew in the tropical Jordan Valley, and around the Dead Sea, to a height of 25 to 50 feet, and bore fruit three or four times a year. They did not grow as well in the higher elevations such as Tekoa, Amos' hometown, so the prophet appears to have farmed at a distance from his home, in addition to tending herds. "Tekoa" stood 10 miles south of Jerusalem in Judah. Thus, Amos seems to have been a prosperous and influential Judahite. However, an older view is that Amos was poor, based on Palestinian practices in the nineteenth century. -

Exploring Zechariah, Volume 2

EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 VOLUME ZECHARIAH, EXPLORING is second volume of Mark J. Boda’s two-volume set on Zechariah showcases a series of studies tracing the impact of earlier Hebrew Bible traditions on various passages and sections of the book of Zechariah, including 1:7–6:15; 1:1–6 and 7:1–8:23; and 9:1–14:21. e collection of these slightly revised previously published essays leads readers along the argument that Boda has been developing over the past decade. EXPLORING MARK J. BODA is Professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is the author of ten books, including e Book of Zechariah ZECHARIAH, (Eerdmans) and Haggai and Zechariah Research: A Bibliographic Survey (Deo), and editor of seventeen volumes. VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Boda Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-201-0) available at http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com Mark J. Boda Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 ANCIENT NEAR EAST MONOGRAPHS Editors Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach C. L. Crouch Esther J. Hamori Chistopher B. Hays René Krüger Graciela Gestoso Singer Bruce Wells Number 17 EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah by Mark J. -

5. Jesus Christ-The Key of David (Isaiah 22:15-25)

1 Jesus Christ, the Key of David Isaiah 22:15-25 Introduction: In Isaiah 22, the Lord sent Isaiah to make an announcement to a government official named Shebna, who served Hezekiah, the king of Judah. The news he had for Shebna was not good. Shebna had, apparently, used his position to increase his own wealth and glory, and had usurped authority which did not belong to him. Shebna received the news that he would soon be abruptly removed from his office. Isaiah also announced that another man (named Eliakim) would take his place, who would administer the office faithfully. This new man would be a type of Jesus Christ. Isaiah 22:15-25 I. The fall of self-serving Shebna (vv. 15-19) In verse 15, the Lord sent Isaiah to deliver a message to Shebna, who was the treasurer in the government of Judah. He is also described as being “over the house.” This particular position was first mentioned in the time of Solomon. (Apparently, the office did not exist in the days of King Saul or King David, because it is not mentioned.) Afterward, it became an important office both in the northern and southern kingdoms. 1 Kings 4:1-6; 16:9; 18:3 2 Kings 10:5 The office of the man who was “over the house” of the king of Judah seems to have increased in importance over time, until it was similar to the Egyptian office of vizier. Joseph had been given this incredibly powerful position in the government of Pharaoh. (In fact, this position seems to have been created, for the first time, in Joseph’s day.) Joseph possessed all the power of the Pharaoh. -

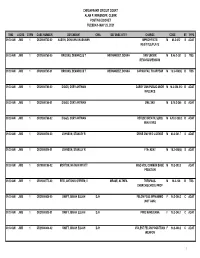

Chesapeake Circuit Court Alan P. Krasnoff, Clerk Posting Docket Tuesday- May 25, 2021

CHESAPEAKE CIRCUIT COURT ALAN P. KRASNOFF, CLERK POSTING DOCKET TUESDAY- MAY 25, 2021 TIME JUDGE CTRM CASE NUMBER DEFENDANT CWA DEFENSE ATTY CHARGE CODE ST TYPE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000762-00 AUSTIN, DONIVAN VAUSHAWN IMPROP/FICTS M 46.2-612 S ADAT REG/TITLE/PLATE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000765-00 BROOKS, DEMARCUS T HERNANDEZ, DONNA DRIV UNDER M B.46.2-301 S TBS REVO/SUSPENSION 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000765-01 BROOKS, DEMARCUS T HERNANDEZ, DONNA CAPIAS FAIL TO APPEAR M 18.2-456(6) B TBS 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-00 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN CARRY GUN PUBLIC-UNDR M 18.2-308.012 B ADAT INFLUNCE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-01 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN DWI, 2ND M B.18.2-266 B ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-02 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN REFUSE BREATH, SUBQ M A.18.2-268.3 B ADAT W/IN 10YRS 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000514-00 JOHNSON, STANLEY R DRIVE CMV W/O LICENSE M 46.2-341.7 S ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000514-01 JOHNSON, STANLEY R FTA- ADAT M 18.2-456(6) S ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR19000796-02 MORTON, NATHAN WYATT MISD VIOL COMMUN BASE M 19.2-303.3 ADAT PRBATION 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000773-00 REID, ANTONIO O'BRIEN; II MEASE, ALTHEA TRESPASS- M 18.2-128 B TBS CHURCH/SCHOOL PROP 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-00 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH FELON POSS WPN/AMMO F 18.2-308.2 C ADAT (NOT GUN) 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-01 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH PWID MARIJUANA F 18.2-248.1 C ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-02 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH VIOLENT FELON POSS/TRAN F 18.2-308.2 C ADAT WEAPON 1 CHESAPEAKE CIRCUIT COURT ALAN P. -

What Is Biblical Prophecy?

What is Biblical Prophecy? What Biblical Prophecy is NOT, and What It Really IS: Contrary to what many fundamentalist preachers or late-night radio hosts would have you believe, biblical prophecy is not primarily about “predicting the future” or finding clues in the Bible that correspond to people or events in our own day and age! The prophets of Ancient Israel did not look into some kind of crystal ball and see events happening thousands of years after their own lifetimes. The books they wrote do not contain hidden coded messages for people living in the 20th or 21st centuries! Rather, biblical prophets were mainly speaking to and writing for the people of their own time. They were challenging people of their own world, especially their political rulers, to remain faithful to God’s commandments and/or to repent and turn back to God if they had strayed. They were conveying messages from God, who had called or commissioned them, rather than speaking on their own initiative or authority. However, because the biblical prophets were transmitting messages on behalf of God (as Jews and Christians believe), much of what they wrote for their own time is clearly also relevant for people living in the modern world. The overall message of faith and repentance is timeless and applicable in all ages and cultures. To understand what biblical prophecy really is, let’s look more closely at the origins, definitions, and uses of some key biblical words. In the Hebrew Bible, the word for “prophet” is usually nabi’ (lit. “spokesperson”; used over 300 times!), while the related feminine noun nebi’ah (“prophetess”) occurs only rarely. -

A Tale of Two Shepherds (Zechariah 10:1-11:17 April 29, 2018)

A Tale Of Two Shepherds (Zechariah 10:1-11:17 April 29, 2018) With many apologies to the great Charles Dickens – the opening lines of his classic work – A Tale Of Two Cities – can with a minor tweak serve to perfectly describe our passage this morning: He was the best of Shepherds, he was the worst of shepherds It was the choice of wisdom, it was the choice of foolishness It was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity It was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness It was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair We had everything before us, we had nothing before us We were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way The best of Shepherds – the worst of shepherds. In a very real sense – the only truly important choice in life can be reduced to which shepherd we entrust our lives to. 1 One Shepherd calls – come to Me all who are weary and heavy laden and I will give you rest. My path is one of sacrifice and suffering – but I will lay down my life for you – and I will never leave you or forsake you – and I will lead you to the green pasture of heaven. The other shepherd calls – come to Me all who are financially challenged and pleasure deficient and I will give you the desires of your heart. My path is one of hedonistic delight – but you must lay down your life for me – and I will leave you as soon as it gets tough – and I cannot lead you to the green pasture of heaven.