Arc of Instability’: the History of an Idea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

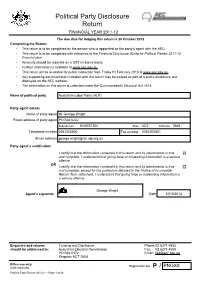

Political Party Return for 2011-12

Political Party Disclosure Return FINANCIAL YEAR 2011-12 The due date for lodging this return is 20 October 2012 Completing the Return: • This return is to be completed by the person who is appointed as the party’s agent with the AEC. • This return is to be completed with reference to the Financial Disclosure Guide for Political Parties 2011-12 financial year. • Amounts should be reported on a GST inclusive basis. • Further information is available at www.aec.gov.au. • This return will be available for public inspection from Friday 01 February 2013 at www.aec.gov.au. • Any supporting documentation included with this return may be treated as part of a public disclosure and displayed on the AEC website. • The information on this return is collected under the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918. Name of political party Australian Labor Party (ALP) Party agent details Name of party agent Mr George Wright Postal address of party agent PO Box 6222 Suburb/town KINGSTON State ACT Postcode 2604 Telephone number 0261200800 Fax number 0261200801 Email address [email protected] Party agent’s certification I certify that the information contained in this return and its attachments is true þ and complete. I understand that giving false or misleading information is a serious offence OR I certify that the information contained in this return and its attachments is true o and complete, except for the particulars detailed in the ‘Notice of Incomplete Return’ form (attached). I understand that giving false or misleading information is a serious offence. -

The Secret Life of Elsie Curtin

Curtin University The secret life of Elsie Curtin Public Lecture presented by JCPML Visiting Scholar Associate Professor Bobbie Oliver on 17 October 2012. Vice Chancellor, distinguished guests, members of the Curtin family, colleagues, friends. It is a great honour to give the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library’s lecture as their 2012 Visiting Scholar. I thank Lesley Wallace, Deanne Barrett and all the staff of the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library, firstly for their invitation to me last year to be the 2012 Visiting Scholar, and for their willing and courteous assistance throughout this year as I researched Elsie Curtin’s life. You will soon be able to see the full results on the web site. I dedicate this lecture to the late Professor Tom Stannage, a fine historian, who sadly and most unexpectedly passed away on 4 October. Many of you knew Tom as Executive Dean of Humanities from 1999 to 2005, but some years prior to that, he was my colleague, mentor, friend and Ph.D. supervisor in the History Department at UWA. Working with Tom inspired an enthusiasm for Australian history that I had not previously known, and through him, I discovered John Curtin – and then Elsie Curtin, whose story is the subject of my lecture today. Elsie Needham was born at Ballarat, Victoria, on 4 October 1890 – the third child of Abraham Needham, a sign writer and painter, and his wife, Annie. She had two older brothers, William and Leslie. From 1898 until 1908, Elsie lived with her family in Cape Town, South Africa, where her father had established the signwriting firm of Needham and Bennett. -

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

Australia, the Southwest Pacific, and United States Interests

Order Code RL32187 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Australia, the Southwest Pacific, and United States Interests January 7, 2004 name redacted and name redacted Analysts in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Australia, the Southwest Pacific, and United States Interests Summary The major U.S. interests in the Southwest Pacific are preventing the rise of terrorist threats, working with and maintaining the region’s U.S. territories, commonwealths, and military bases (American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the Reagan Missile Test Site on Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands), and enhancing U.S.-Australian cooperation in pursuing mutual political, economic, and strategic objectives in the area. The United States and Australia share common interests in countering transnational crime and preventing the infiltration of terrorist organizations in the Southwest Pacific, hedging against the growing influence of China, and promoting political stability and economic development. The United States has supported Australia’s increasingly proactive stance and troop deployment in Pacific Island nations torn by political and civil strife such as East Timor, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. Australia may play a greater strategic role in the region as the United States seeks to redeploy its Asia-Pacific force structure. This report will be updated as needed. Contents U.S. Interests in the Southwest Pacific .................................1 The Evolving U.S.-Australian Strategic Relationship......................2 Australia’s Role in the Region........................................5 China’s Growing Regional Influence...................................6 List of Figures Figure 1. Map of the Southwest Pacific ................................7 Australia, the Southwest Pacific, and United States Interests U.S. -

Geography, Power, Strategy & Defence Policy

GEOGRAPHY, POWER, STRATEGY & DEFENCE POLICY ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF PAUL DIBB GEOGRAPHY, POWER, STRATEGY & DEFENCE POLICY ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF PAUL DIBB Edited by Desmond Ball and Sheryn Lee Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Geography, power, strategy and defence policy : essays in honour of Paul Dibb / editors: Desmond Ball, Sheryn Lee. ISBN: 9781760460136 (paperback) 9781760460143 (ebook) Subjects: Dibb, Paul, 1939---Criticism and interpretation. Defensive (Military science) Military planning--Australia. Festschriften. Australia--Military policy. Australia--Defenses. Other Creators/Contributors: Ball, Desmond, 1947- editor. Lee, Sheryn, editor. Dewey Number: 355.033594 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: SDSC Photograph Collection. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents Acronyms ..............................................vii Contributors ............................................ xi Photographs and Maps ..................................xvii Introduction .............................................1 Desmond Ball and Sheryn Lee 1. Introducing Paul Dibb (1): Britain’s Loss, Australia’s Gain ......15 Allan Hawke 2. Introducing Paul Dibb (2): An Enriching Experience ...........21 Chris Barrie 3. Getting to Know Paul Dibb: An Overview of an Extraordinary Career ..................................25 Desmond Ball 4. Scholar, Spy, Passionate Realist .........................33 Geoffrey Barker 5. The Power of Geography ..............................45 Peter J. Rimmer and R. Gerard Ward 6. The Importance of Geography ..........................71 Robert Ayson 7. -

Reality Check: Australia's China Shift Came Before Trump

Reality check: Australia’s China shift came before Trump James Laurenceson February 9 2017 Note: This article appeared in The Diplomat, February 9 2017. Last year, defense hawks in the United States and Australia were handed a rude shock. A poll by the Sydney- based Lowy Institute revealed that 43 percent of Australians thought the country’s most important relationship was with the United States. The very same proportion said that it was with China. Another poll by the U.S. Studies Center at the University of Sydney found that 48 percent of Australians thought the relationship with China should be stronger, compared with 32 percent who said the same about the United States. It is against this background that new U.S. President Donald Trump spoke to Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull last week. After having had conversations with several other world leaders, including Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Trump reportedly told Turnbull that his was the “worst phone call by far.” As part of a discussion over a U.S.-Australia refugee resettlement plan, Trump accused Turnbull of trying to send the “next Boston bombers” to the United States. Trump counsellor Kellyanne Conway then blamed Australia for leaking details of the conversation, despite the earliest reports citing White House sources, only later confirmed by Australian ones. In any case, Trump himself had fired off a tweet calling the refugee resettlement plan Turnbull had struck with the former Obama administration “a dumb deal.” Many commentators declared China to be the big winner from the episode. But to focus only on the fallout of the phone call would be to miss a shift that was already underway. -

Public Financing of Health Care in Eight Western Countries

PUBLIC FINANCING OF HEALTH CARE IN EIGHT WESTERN COUNTRIES The Introduction of Universal Coverage BY ALEXANDER SHALOM PREKER Ph.D. Thesis Submitted to Fulfill Requirements for a Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the London School of Economics and Political Science UMI Number: U048587 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U048587 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 rnsse F 686 X c2I ABSTRACT The public sector of all western developed countries has become increasingly involved in financing health care during the past century. Today, thirteen OECD countries have passed landmark legislative reforms that call for compulsory prepayment and universal entitlement to comprehensive services, while most of the others achieve similar coverage through a mixture of public and private voluntary arrangements. This study carried out a detailed analysis of why, how and to what effect governments became involved in health care financing in eight of these countries. During the early phase of this evolution, reliance on direct out-of-pocket payment and an unregulated market mechanism for the financing, production and delivery of health care led to many unsatisfactory outcomes in the allocation of scarce resources, redistribution of the financial burden of illness and stabilisation of health care activities. -

Australia: Background and U.S

Order Code RL33010 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Australia: Background and U.S. Relations Updated April 20, 2006 Bruce Vaughn Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Australia: Background and U.S. Interests Summary The Commonwealth of Australia and the United States are close allies under the ANZUS treaty. Australia evoked the treaty to offer assistance to the United States after the attacks of September 11, 2001, in which 22 Australians were among the dead. Australia was one of the first countries to commit troops to U.S. military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. In October 2002, a terrorist attack on Western tourists in Bali, Indonesia, killed more than 200, including 88 Australians and seven Americans. A second terrorist bombing, which killed 23, including four Australians, was carried out in Bali in October 2005. The Australian Embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia, was also bombed by members of Jemaah Islamiya (JI) in September 2004. The Howard Government’s strong commitment to the United States in Afghanistan and Iraq and the recently negotiated bilateral Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between Australia and the United States have strengthened what were already close ties between the two long-term allies. Despite the strong strategic ties between the United States and Australia, there have been some signs that the growing economic importance of China to Australia may influence Australia’s external posture on issues such as Taiwan. Australia plays a key role in promoting regional stability in Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific. -

Inside the Canberra Press Gallery: Life in the Wedding Cake of Old

INSIDE the CANBERRA PRESS GALLERY Life in the Wedding Cake of Old Parliament House INSIDE the CANBERRA PRESS GALLERY Life in the Wedding Cake of Old Parliament House Rob Chalmers Edited by Sam Vincent and John Wanna THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Chalmers, Rob, 1929-2011 Title: Inside the Canberra press gallery : life in the wedding cake of Old Parliament House / Rob Chalmers ; edited by Sam Vincent and John Wanna. ISBN: 9781921862366 (pbk.) 9781921862373 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Australia. Parliament--Reporters and Government and the press--Australia. Journalism--Political aspects-- Press and politics--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Vincent, Sam. Wanna, John. Dewey Number: 070.4493240994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Back cover image courtesy of Heide Smith Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Foreword . ix Preface . xi 1 . Youth . 1 2 . A Journo in Sydney . 9 3 . Inside the Canberra Press Gallery . 17 4 . Menzies: The giant of Australian politics . 35 5 . Ming’s Men . 53 6 . Parliament Disgraced by its Members . 71 7 . Booze, Sex and God . -

1 Army in the 21 Century and Restructuring the Army: A

Army in the 21st Century and Restructuring the Army: A Retrospective Appraisal of Australian Military Change Management in the 1990s Renée Louise Kidson July 2016 A sub-thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Military and Defence Studies (Advanced) of The Australian National University © Copyright by Renée Louise Kidson 2016 All Rights Reserved 1 Declaration This sub-thesis is my own original work. I declare no part of this work has been: • copied from any other person's work except where due acknowledgement is made in the text; written by any other person; or • submitted for assessment in another course. The sub-thesis word count is 16,483 excluding Table of Contents, Annexes and Chapter 2 (Literature Review and Methods, a separate assessment under the MMDS(Adv) program). Renee Kidson Acknowledgements I owe my greatest thanks to my supervisors: Dr John Blaxland (ANU) and Colonel David Connery (Australian Army History Unit, AAHU), for wise counsel, patience and encouragement. Dr Roger Lee (Head, AAHU) provided funding support; and, crucially, a rigorous declassification process to make select material available for this work. Lieutenant Colonel Bill Houston gave up entire weekends to provide my access to secure archival vault facilities. Meegan Ablett and the team at the Australian Defence College Vale Green Library provided extensive bibliographic support over three years. Thanks are also extended to my interviewees: for the generosity of their time; the frankness of their views; their trust in disclosing materially relevant details to me; and for providing me with perhaps the finest military education of all – insights to the decision-making processes of senior leaders: military and civilian. -

Timbuckleyieefa DIRTY POWER BIG COAL's NETWORK of INFLUENCE OVER the COALITION GOVERNMENT CONTENTS

ICAC investigation: Lobbying, Access and Influence (Op Eclipse) Submission 2 From: Tim Buckley To: Lobbying Subject: THE REGULATION OF LOBBYING, ACCESS AND INFLUENCE IN NSW: A CHANCE TO HAVE YOUR SAY Date: Thursday, 16 May 2019 2:01:39 PM Attachments: Mav2019-GPAP-Dirtv-Power-Report.Ddf Good afternoon I am delighted that the NSW ICAC is looking again into the issue of lobbying and undue access by lobbyists representing self-serving, private special interest groups, and the associated lack of transparency. This is most needed when it relates to the private (often private, foreign tax haven based entities with zero transparency or accountability), use of public assets. IEEFA works in the public interest analysis relating to the energy-fmance-climate space, and so we regularly see the impact of the fossil fuel sector in particular as one that thrives on the ability to privatise the gains for utilising one-time use public assets and in doing so, externalising the costs onto the NSW community. This process is constantly repeated. The community costs, be they in relation to air, particulate and carbon pollution, plus the use of public water, and failure to rehabilitate sites post mining, brings a lasting community cost, particularly in the area of public health costs. The cost-benefit analysis presented to the IPC is prepared by the proponent, who has an ability to present biased self-serving analysis that understates the costs and overstates the benefits. To my understanding, the revolving door of regulators, politicians, fossil fuel companies and their lobbyists is corrosive to our democracy, undermining integrity and fairness. -

1 Tony Abbott: the Argument for Central Government Santo Santoro

September 2005 Issue 1 www.conservative.com.au Tony Abbott: the argument for central government Santo Santoro: the case for federalism Gerry Wheeler: federalism & VSU 1 contents September 2005 Issue 1 www.conservative.com.au FOCUS ON FEDERALISM 4 Tony Abbott A CONSERVATIVE CASE FOR CENTRALISM 6 Santo Santoro IN DEFENCE OF FEDERALISM 13 Gerry Wheeler VOLUNTARY STUDENT UNIONISM - LESSONS FROM THE STATES THEORY AND PHILOSOPHY 17 Alastair Furnival THE CHALLENGES OF A MODERN CONSERVATISM 21 Mike Pence STATE OF THE CONSERVATIVE MOVEMENT POLICY 25 Nick Minchin PATRON: Senator Hon. Nick Minchin WHY WE SHOULD SELL TELSTRA EDITORIAL COMMITTEE: Senator Santo Santoro (editor) 28 Alexander Downer Alastair Furnival (excutive editor) ON HISTORY AND LIBERTY Senator Concetta Fierravanti-Wells Gerry Wheeler David Stevens 33 Michael Brennan PUBLISHER: FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY Conservative Publications Pty Ltd VS SMALLER GOVERNMENT GPO Box 1600 Sydney NSW 2000 38 Concetta Fierravanti-Wells ph: 02 9234 3838 fax: 02 9234 3800 [email protected] IMMIGRATION AND SOCIETY These days it seems that serious consideration of ideas which are mainstream, quintessentially Australian, and in the public interest is often sidelined by the pursuit of more superficial issues. It has become apparent to those associated with this enterprise that there is a need for a journal - namely the conservative - to unashamedly raise issues which are increasingly prominent in the political, economic and social consciousness of our country’s activists: and to do so through the prism of progressive Liberal thought. In this inaugural issue of the conservative there is focus on the growing debate about federalism - an issue which touches the very core and foundations of our system of government.