Australian Muslim Leaders, Normalisaton and Social Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

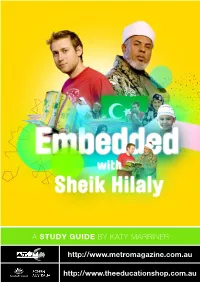

A Study Guide by Katy Marriner

A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ing scantily-dressed women to uncovered meat. But Dave is determined to uncover the man behind the controversy, and attempt to better understand Islam and Australian–Muslim culture in the process. To make Dave’s experience more authentic, Sheik Hilaly insists that he observe all Muslim practices. This includes praying five times a day, attend- ing mosque and not eating his usual breakfast of bacon and eggs. Dave is also expected to follow Sheik Hilaly’s rules when it comes to hygiene. It doesn’t take long for Dave to realize that his immersion experience is not going to be without some very personal challenges. To gain a better understanding of the Islamic com- munity in Australia, Dave speaks to Sheik Hilaly’s good friend, boxer Anthony Mundine, about his conversion. He also speaks to a newly married couple about relationships and to a young woman about freedom of choice. In a bid to find out why some Australians are so afraid of Islam, Dave trav- This study guide to accompany Embedded with Sheik els to Camden in south-west Sydney where earlier Hilaly, a documentary by Red Ithaka Productions, this year, locals rejected a plan to build a Muslim has been written for secondary students. It provides school. There, Dave meets with anti-Islamic activist Katie McCullough, a woman who caused a bit of a information and suggestions for learning activities in stir of her own when she voiced her strong opposi- English, International Studies, Media, Religion, SOSE tion to Muslims living in her community. -

Penelitian Individual

3 ii COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH (THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND-STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY WALISONGO) GENDER AND IDENTITY POLITICS (DYNAMICS OF MOSLEM WOMEN IN AUSTRALIA) Researchers: Misbah Zulfa Elizabeth Lift Anis Ma’shumah Nadiatus Salama Academic Advisor: Dr. Morgan Brigg Dr. Lee Wilson Funded by DIPA UIN Walisongo 2015 iii iv PREFACE This research, entitled Gender and Identity Politics (Dynamics of Moslem Women in Australia) is implemented as the result of cooperation between State Islamic University Walisongo and The University of Queensland (UQ) Brisbane Australia for the second year. With the completion of this research, researchers would like to say thank to several people who have helped in the processes as well as in the completion of the research . They are 1 Rector of State Islamic University Walisongo 2. Chairman of Institute for Research and Community Service (LP2M) State Islamic University Walisongo 3. Chancellor of The UQ 4. Academic advisor from The UQ side : Dr. Morgan Brigg and Dr. Lee Wilson 5. All those who have helped the implementation of this study Finally , we must state that these report has not been perfect . We are sure there are many limitedness . Therefore, we are happy to accept criticism , advice and go for a more refined later . Semarang, December 2015 Researchers v vi TABLE OF CONTENT PREFACE — v TABLE OF CONTENT — vi Chapter I. Introduction A. Background — 1 B. Research Question — 9 C. Literature Review — 9 D. Theoretical Framework — 14 E. Methods — 25 Chapter II. Identity Politics and Minority-Majority Relation among Women A. Definition of Identity Politics — 29 B. Definition of Majority-Minority — 36 C. -

Australia: Extremism and Terrorism

Australia: Extremism and Terrorism On March 17, 2021, authorities arrested brothers Aran and Ari Sherani, ages 19 and 20 respectively, during counterterrorism raids in Melbourne after Aran allegedly purchased a knife in preparation for a terrorist attack. Police alleged Aran was influenced by ISIS. Both brothers were charged in relation to a February 21 attempted attack in Humevale, in which a fire was lit in bushland outside of Melbourne. Aran Shirani also faces charges in relation to a March 9 assault that left one injured. Authorities allege Aran Shirani radicalized online and then radicalized his older brother. (Sources: Guardian, 9News, Australian Press Association) On December 17, 2020, 22-year-old Raghe Abdi threated Australian police officers with a knife on a highway outside of Brisbane and was then shot dead by the authorities. According to police, Abdi was influenced by ISIS. That same day, 87-year-old Maurice Anthill and his 86-year-old wife Zoe were found dead inside their home in Brisbane, where Abdi was believed to have been. Police Commissioner Katarina Carroll Abdi said that though Abdi was a known extremist, the suspect had acted alone, and declared the deaths a terrorism incident. Abdi was arrested on suspicion of joining extremist groups while he attempted to board a flight to Somalia in May 2019. He was released due to lack of evidence, though his passport was canceled. Abdi was again charged in June 2019 on other offenses, including not providing his cellphone passcode to investigators but was freed on bail and given a GPS tracking device to wear. -

Muslim Community Organizations in the West History, Developments and Future Perspectives Islam in Der Gesellschaft

Islam in der Gesellschaft Mario Peucker Rauf Ceylan Editors Muslim Community Organizations in the West History, Developments and Future Perspectives Islam in der Gesellschaft Herausgegeben von R. Ceylan, Osnabrück, Deutschland N. Foroutan, Berlin, Deutschland A. Zick, Bielefeld, Deutschland Die neue Reihe Islam in der Gesellschaft publiziert theoretische wie empirische Forschungsarbeiten zu einem international wie national aktuellem Gegenstand. Der Islam als heterogene und vielfältige Religion, wie aber auch kulturelle und soziale Organisationsform, ist ein bedeutsamer Bestandteil von modernen Gesell- schaften. Er beeinflusst Gesellschaft, wird zum prägenden Moment und erzeugt Konflikte. Zugleich reagieren Gesellschaften auf den Islam und Menschen, die im angehören bzw. auf das, was sie unter dem Islam und Muslimen verstehen. Der Islam prägt Gesellschaft und Gesellschaft prägt Islam, weil und wenn er in Gesellschaft ist. Die damit verbundenen gesellschaftlichen Phänomene und Pro zesse der Veränderungen sind nicht nur ein zentraler Aspekt der Integrations- und Migrationsforschung. Viele Studien und wissenschaftliche Diskurse versuchen, den Islam in der Gesellschaft zu verorten und zu beschreiben. Diese Forschung soll in der Reihe Islam in der Gesellschaft zu Wort und Schrift kommen, sei es in Herausgeberbänden oder Monografien, in Konferenzbänden oder herausragenden Qualifikationsarbeiten. Die Beiträge richten sich an unterschiedliche Disziplinen, die zu einer inter- wie transdisziplinären Perspektive beitragen können: - Sozial wissenschaften, -

Identification Laws Amendment Bill 2013

Identification Laws Amendment Bill 2013 Report No. 49 Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee February 2014 Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee Chair Mr Ian Berry MP, Member for Ipswich Deputy Chair Mr Peter Wellington MP, Member for Nicklin Members Miss Verity Barton MP, Member for Broadwater Mr Bill Byrne MP, Member for Rockhampton Mr Sean Choat MP, Member for Ipswich West Mr Aaron Dillaway MP, Member for Bulimba Mr Trevor Watts MP, Member for Toowoomba North Staff Mr Brook Hastie, Research Director Mrs Ali Jarro, Principal Research Officer Ms Kelli Longworth, Principal Research Officer Ms Kellie Moule, Principal Research Officer Mr Greg Thomson, Principal Research Officer Mrs Gail Easton, Executive Assistant Technical Scrutiny Mr Peter Rogers, Acting Research Director Secretariat Mr Karl Holden, Principal Research Officer Ms Tamara Vitale, Executive Assistant Contact details Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee Parliament House George Street Brisbane Qld 4000 Telephone +61 7 3406 7307 Fax +61 7 3406 7070 Email [email protected] Web www.parliament.qld.gov.au/lacsc Identification Laws Amendment Bill 2013 Contents Abbreviations iv Chair’s foreword v Recommendations vi 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Role of the Committee 1 1.2 Referral 1 1.3 Inquiry process 1 1.4 Policy objectives of the Identification Laws Amendment Bill 2013 2 1.5 Consultation on the Bill 2 2. Examination of the Identification Laws Amendment Bill 2013 3 2.1 Policy reasons for the Bill 3 2.2 Comparable laws 3 2.3 Terms used in the Bill 4 2.4 Discrimination concerns 4 2.5 Request by Police to confirm identity 6 2.6 Witnessing requirements 8 2.7 Entry to secure buildings 10 2.8 Should the Bill be passed? 11 3. -

Law and Liberty in the War on Terror

LAW AND LIBERTY IN THE WAR ON TERROR EDITORS Andrew Lynch Edwina MacDonald George Williams FOREWORD The Hon Sir Gerard Brennan AC KBE THE FEDERATION PRESS 2007 Published in Sydney by: The Federation Press PO Box 45, Annandale, NSW, 2038 71 John St, Leichhardt, NSW, 2040 Ph (02) 9552 2200 Fax (02) 9552 1681 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.federationpress.com.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Law and Liberty in the war on terror Editors: Andrew Lynch; George Williams; Edwina MacDonald. Includes index. Bibliography ISBN 978 186287 674 3 (pbk) Judicial power – Australia. Criminal Law – Australia. War on Terrorism, 2001- Terrorism – Prevention. Terrorism. International offences. 347.012 © The Federation Press This publication is copyright. Other than for the purposes of and subject to the conditions prescribed under the Copyright Act, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. Typeset by The Federation Press, Leichhardt, NSW. Printed by Ligare Pty Ltd, Riverwood, NSW. Contents Foreword – Sir Gerard Brennan v Preface xii Contributors xiii Part I Law’s Role in the Response to Terrorism 1 Law as a Preventative Weapon Against Terrorism 3 Philip Ruddock 2 Legality and Emergency – The Judiciary in a Time of Terror 9 David Dyzenhaus and Rayner Thwaites 3 The Curious Element of Motive -

Australia's Multicultural Identity in the Asian Century

Australia’s Multicultural Identity in the Asian Century Australia’s Multicultural Identity in the Asian Century Waleed Aly Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia 1 Australia’s Multicultural Identity in the Asian Century © 2014 Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia 1 Persiaran Sultan Salahuddin PO Box 12424 50778 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia http://www.isis.org.my All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise, without the prior permission of the publisher. The views and opinions expressed in this book are those of the author and may not necessarily reflect those of ISIS Malaysia. ISBN: 978-967-947-312-4 Printed by Aura Productions Sdn Bhd 2 Australia’s Multicultural Identity in the Asian Century Australia’s Multicultural Identity in the Asian Century Perhaps the best way to begin the story of Australia’s multicultural identity in the Asian Century is to start in the 17th century in Europe. In truth, this is a useful starting point for any discussion of diversity within a nation, and the way that nation manages its diversity, because it forces us to think about the concept of the nation itself, and the very essence of national identity. That essence begins with the treaties of Westphalia. It is no exaggeration to say that the doctrines on which the nation state is built were born in those treaties. So, too, the nation state’s attendant mythologies. And here we must admit that in spite of whatever politicians might want to say, the nation state is a mythologized fiction that we keep alive through the way that we talk about it. -

Who Gets to Tell Australian Stories?

Who Gets To Tell Australian Stories? Putting the spotlight on cultural and linguistic diversity in television news and current affairs The Who Gets To Tell Australian Stories? report was prepared on the basis of research and support from the following people: Professor James Arvanitakis (Western Sydney University) Carolyn Cage (Deakin University) Associate Professor Dimitria Groutsis (University of Sydney) Dr Annika Kaabel (University of Sydney) Christine Han (University of Sydney) Dr Ann Hine (Macquarie University) Nic Hopkins (Google News Lab) Antoinette Lattouf (Media Diversity Australia) Irene Jay Liu (Google News Lab) Isabel Lo (Media Diversity Australia) Professor Catharine Lumby (Macquarie University) Dr Usha Rodrigues (Deakin University) Professor Tim Soutphommasane (University of Sydney) Subodhanie Umesha Weerakkody (Deakin University) This report was researched, written and designed on Aboriginal land. Sovereignty over this land was never ceded. We wish to pay our respect to elders past, present and future, and acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities’ ongoing struggles for justice and self-determination. Who Gets to Tell Australian Stories? Executive summary The Who Gets To Tell Australian Stories? report is the first comprehensive picture of who tells, frames and produces stories in Australian television news and current affairs. It details the experience and the extent of inclusion and representation of culturally diverse news and current affairs presenters, commentators and reporters. It is also the first -

FAA-Industry-Smiles Turner Submission

THE CLASH BETWEEN IDEALISM AND REALITY A SUBMISSION to the SENATE ECONOMICS LEGISLATION COMMITTEE INQUIRY into the Consumer Credit and Corporations Legislation Amendment (Enhancements) Bill 2011: formerly the Exposure Draft entitled the National Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Enhancements) Bill 2011 from the FINANCIERS’ ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA / INDUSTRY / SMILES TURNER DELEGATION Consultants: Phillip Smiles LL.B., B.Ec., M.B.A., Dip.Ed. Lyn Turner M.A., Dip.Drama Smiles Turner Ph: (02) 9975 4244 Fax: (02) 9975 6877 Email: [email protected] © Smiles Turner, November 2011 1 “You certainly, in a modern economy can’t regulate interest rates. That’s economics discarded for the last 30 years.” - Prime Minister Julia Gillard, 4 November 2010, Today Show, TCN Channel 9 © Smiles Turner, November 2011 2 INDEX Content Page Executive Summary 4 About this Submission 11 Section 1 - Market Characteristics and Supply Realities 14 If the Bill Proceeds to Enactment Unchanged 14 Section 2 - The Delegation’s Simple Alternative 24 Section 3 - A Detailed Analysis of the Current Bill 30 Section 32A 49 Section 4 - Explanatory Memorandum and RIS Deficient 57 Concerns in Regard to the Explanatory Memorandum 57 An Analysis of the Regulation Impact Statement 65 A Major Government Study Ignored by Treasury 76 An Analysis of the Minister’s Second Reading Speech 77 Section 5 - Non-Commercial Alternatives Grossly Inadequate 81 Decisions Demanding Alternatives, Without Timely Research 81 Not-for -profit, Non-commercial Credit Opportunities 82 Other Possible -

Judicial System in India During Mughal Period with Special Reference to Persian Sources

Judicial System in India during Mughal Period with Special Reference to Persian Sources (Nezam-e-dadgahi-e-Hend der ahd-e-Gorkanian bewizha-e manabe-e farsi) For the Award ofthe Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submitted by Md. Sadique Hussain Under the Supervision of Dr. Akhlaque Ahmad Ansari Center Qf Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi -110067. 2009 Center of Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi -110067. Declaration Dated: 24th August, 2009 I declare that the work done in this thesis entitled "Judicial System in India during Mughal Period with special reference to Persian sources", for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy, submitted by me is an original research work and has not been previously submitted for any other university\Institution. Md.Sadique Hussain (Name of the Scholar) Dr.Akhlaque Ahmad Ansari (Supervisor) ~1 C"" ~... ". ~- : u- ...... ~· c "" ~·~·.:. Profess/~ar Mahdi 4 r:< ... ~::.. •• ~ ~ ~ :·f3{"~ (Chairperson) L~.·.~ . '" · \..:'lL•::;r,;:l'/ [' ft. ~ :;r ':1 ' . ; • " - .-.J / ~ ·. ; • : f • • ~-: I .:~ • ,. '· Attributed To My Parents INDEX Acknowledgment Introduction 1-7 Chapter-I 8-60 Chapter-2 61-88 Chapter-3 89-131 Chapter-4 132-157 Chapter-S 158-167 Chapter-6 168-267 Chapter-? 268-284 Chapter-& 285-287 Chapter-9 288-304 Chapter-10 305-308 Conclusion 309-314 Bibliography 315-320 Appendix 321-332 Acknowledgement At first I would like to praise God Almighty for making the tough situations and conditions easy and favorable to me and thus enabling me to write and complete my Ph.D Thesis work. -

Muslim Youth and the Mufti

Muslim Youth and the Mufti: Youth discourses on identity and religious leadership under media scrutiny S. Ihram Masters Honours Degree 2009 University of Western Sydney IN THANKS: To Allah the All Compassionate for allowing me to attempt this work... To my husband and children for supporting me throughout this work... To Haneefa and Adam – you made life easier To my supervisors – Dr. Greg Noble, Dr. Scott Poynting and Dr. Steven Drakeley To the tranquil cafes of Brisbane for providing inspiration.. To my Muslim community – that we may be reminded, and there may be some be some benefit in the reminder. STATEMENT OF AUTHENTICATION: The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .................................................. Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................... iii Chapter 1: Background ............................................................................................................ 1 Literature Review ............................................................................................................... 10 Arabic Background Muslim Community in Australia ....................................................... 10 Citizenship and Inclusion .................................................................................................. -

Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism

Economies of Abandonment Algerian War, ’��-’�� Socialism w/ Chinese Characteristics, ’�� Bretton Woods, ’��; Marshall Plan, ’��; Gold Standard Collapse, ’�� Opec Embargo, ’�� Asian Financial Nonaligned Crisis, ’�� US Withdraws Movement, ’�� Berlin Wall from Vietnam, ’�� Falls, ’�� ���� ���� ���� ���� ���� � Tasmanian Greens ’��; British Greens ’��; French & German Greens, ’��; Israel, ��; Suez, �� ’ ’ Zapistista ’��; Landless Peoples Movement, ’�� March on Washington, ’��; Stonewall Riots, ’��; Wounded Knee, ’�� Keynesian Economics Neo-Liberalism White Man’s Burden Cultural Recognition Civilizational Securi Housing Prices in Darwin, �� Wages & Prices Accord, ’��; Workplace Relations Act, ’��; ���k, ’��; ����k, ’��; ����k, ’��; Maritime Union Strike, ’�� ����k, ’�� ���� ���� ���� ���� ���� � Constitution Alteration (Aboriginal People), ’�� Aboriginal Land Rights (��) Act, ’�� High Court, Mabo v Queensland, ’�� Native Title Act, ’�� High Court, Wik: Pastoral Leases trump Native Title, ��� land affected, ’�� Liberal Gov’t cuts ���� million from Indigenous programs, ’�� EconomiesofAbandonment Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism Al-Qaeda Attacks US, ’�� Financial Markets Collapse, ’�� Elizabeth A.Povinelli ��� ���� ���� Keynesian Economics Neo-Liberalism Anarcho Liberalism s Burden Cultural Recognition Civilizational Securitization Australian �: ��c, ’��; ��c, ’��; ��c, ’��; ��c, ’�� ��� ���� ���� Liberal Gov’t abolishes Aboriginal & Torres Islanders Commission, ’�� Duke University Press Liberal Gov’t declares Emergency Intervention