Australia's Multicultural Identity in the Asian Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law and Liberty in the War on Terror

LAW AND LIBERTY IN THE WAR ON TERROR EDITORS Andrew Lynch Edwina MacDonald George Williams FOREWORD The Hon Sir Gerard Brennan AC KBE THE FEDERATION PRESS 2007 Published in Sydney by: The Federation Press PO Box 45, Annandale, NSW, 2038 71 John St, Leichhardt, NSW, 2040 Ph (02) 9552 2200 Fax (02) 9552 1681 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.federationpress.com.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Law and Liberty in the war on terror Editors: Andrew Lynch; George Williams; Edwina MacDonald. Includes index. Bibliography ISBN 978 186287 674 3 (pbk) Judicial power – Australia. Criminal Law – Australia. War on Terrorism, 2001- Terrorism – Prevention. Terrorism. International offences. 347.012 © The Federation Press This publication is copyright. Other than for the purposes of and subject to the conditions prescribed under the Copyright Act, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. Typeset by The Federation Press, Leichhardt, NSW. Printed by Ligare Pty Ltd, Riverwood, NSW. Contents Foreword – Sir Gerard Brennan v Preface xii Contributors xiii Part I Law’s Role in the Response to Terrorism 1 Law as a Preventative Weapon Against Terrorism 3 Philip Ruddock 2 Legality and Emergency – The Judiciary in a Time of Terror 9 David Dyzenhaus and Rayner Thwaites 3 The Curious Element of Motive -

Australian Journey Resource Guide

Episode Eight: An Australian Way of Life Supplement: Susan Carland in conversation with Dr Waleed Aly Extend your knowledge of post war Australia and contemporary Australian sport, culture and society Four Texts to Read Three Websites to Visit • David Day, Chifley (Sydney: HarperCollins, 2001) • Menzies Virtual Museum • David Lowe, Menzies and the ‘Great World — https://menziesvirtualmuseum.org.au/the- Struggle’: Australia’s Cold War, 1948-1954 1950s/1950 (Sydney: UNSW Press, 1999). • ‘Election of Menzies’, National Museum of • Stuart Macintyre, Australia’s Boldest Experiment: Australia War and Reconstruction in the 1940s (Sydney: — http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/ New South 2015) primeministers/menzies/in-office.aspx • John Murphy, Imagining the Fifties: Private • ‘Australia in the 1950s’, My Place for Teachers Sentiment and Political Culture in Menzies’ — http://www.myplace.edu.au/decades_ Australia (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2000). timeline/1950/decade_landing_5. html?tabRank=1 Resources for the Journey 17 Podcasts to listen to Film and Literature • ‘Historyonics: Chifley’s Light on the Hill’,RN Drive, • TV Series: True Believers, episode #1 (ABC, 1988) 4 September 2013 — Available on YouTube: https://www. — Summary: Ben Chifley’s Light on the Hill youtube.com/watch?v=mcbEylfaXgM speech has become a seminal speech • Novel: Ruth Park, Poor Man’s Orange (Sydney: for the Australian Labor Party. Speaking at Angus and Robertson, 1949) the ALP conference in June 1949, Chifley urged the Labor faithful to continue to fight for a better society for -

2014–15 Annual Report

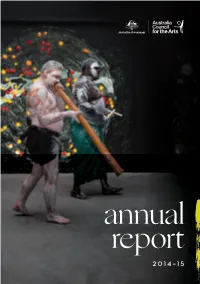

annual report 2 0 1 4 – 1 5 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Minister for the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 26 August 2015 Dear Minister, On behalf of the Board of the Australia Council, I am pleased to submit the Australia Council Annual Report for 2014–15. The Board is responsible for the preparation and content of the annual report pursuant to section 46 of the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013, the Commonwealth Authorities (Annual Reporting) Order 2011 and the Australia Council Act 2013. The following report of operations and financial statements were adopted by resolutions of the Board on the 26 August 2015. Yours faithfully, Rupert Myer AO Chair, Australia Council CONTENTS Our purpose 3 Report from the Chair 4 Report from the CEO 8 Section 1: Agency Overview 12 About the Australia Council 15 2014–15 at a glance 17 Structure of the Australia Council 18 Organisational structure 19 Funding overview 21 New grants model 28 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts 32 Supporting Arts Organisations 34 Major Performing Arts Companies 36 Key Organisations and Territory Orchestras 38 Achieving a culturally ambitious nation 41 Government initiatives 60 Arts Research 64 Section 2: Report on Performance Outcomes 66 Section 3: Management and Accountability 72 The Australia Council Board 74 Committees 81 Management of Human Resources 90 Ecologically sustainable development 93 Executive Team at 30 June 2015 94 Section 4: Financial Statements 96 Compliance index 148 Cover: Matthew Doyle and Djakapurra Munyarryun at the opening of the Australian Pavilion in Venice. Image credit: Angus Mordant Unicycle adagio with Kylie Raferty and April Dawson, 2014, Cirus Oz. -

Keys CV 2020 Public

Barbara (Ara) Keys History Department 43 North Bailey Durham University Durham DH1 3EX, United Kingdom ORCID ID: 0000-0002-8026-4932 E-mail: [email protected] Personal website: http://www.barbarakeys.com Twitter: @arakeys EDUCATION Ph.D. in History, Harvard University, 2001 Fields: International History since 1815; United States since 1789; Modern Russia; Medieval Russia (Akira Iriye, Ernest May, Terry Martin) A.M. in History, Harvard University, 1996 M.A. in History, University of Washington, 1992 B.A. in History, summa cum laude, Carleton College (Northfield, MN), 1987 POSITIONS Durham University Professor, History Department, 2020- University of Melbourne Assistant Dean (Research), Faculty of Arts, 2018-2019 Professor, History, 2019 Associate Professor, History, 2015-2018 Senior Lecturer, History, 2009-2014 Lecturer, History, 2006-2009 California State University, Sacramento Assistant Professor, History Department, 2003-2005 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Research Scholar, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies, 2003 OTHER Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte, Mainz Senior Research Fellow, Spring 2017 Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin Visiting Scholar, Center for the History of Emotions, Spring 2016 Harvard University Visiting Scholar, Center for European Studies, Fall 2012 University of California, Berkeley Visiting Scholar, Center for the Study of Law and Society, Spring 2009 PROFESSIONAL RECOGNITION ___________________________________________________________________________ President -

Inaugural Indonesia-Australia Dialogue 4-6 October 2011

Australian Institute of International Affairs Inaugural Indonesia-Australia Dialogue 4-6 October 2011 Jointly organised by Australian Institute of International Affairs and the Centre for Strategic and International Studies Supported by Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australia and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Indonesia Australian Institute of International Affairs Outcomes Report The inaugural Indonesia-Australia Dialogue was held in Jakarta from 4-6 October 2011. The Indonesia-Australia Dialogue initiative was jointly announced by leaders during the March 2010 visit to Australia by Indonesian President Yudhoyono as a bilateral second track dialogue to enhance people-to-people links between the two countries. The inaugural Indonesia-Australia Dialogue was co- convened by Mr John McCarthy, AIIA National President and former Ambassador to Indonesia, and Dr Rizal Sukma, Executive Director of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies. The AIIA was selected by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to act as secretariat for the Dialogue. Highlights of the Dialogue included: Participation by an impressive Australian delegation including politicians, senior academic and media experts as well as leaders in business, science and civil society. Two days of Dialogue held in an atmosphere of open exchange with sharing of expertise and insights at a high level among leading Indonesian and Australian figures. Messages from Prime Minister Gillard and Minister for Foreign Affairs Rudd officially opening the Dialogue. Opening attended by Australian Ambassador to Indonesia HE Mr Greg Moriarty and Director General of Asia Pacific and African Affairs HE Mr Hamzah Thayeb. Meeting with Indonesia’s Foreign Minister, Marty Natalegawa at Gedung Pancasila, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. -

David Foster Wallace's Final Novelp8

FREE APRIL 2011 Readings Monthly Patrick Allington on Jane Sullivan • Benjamin Law on Cory Taylor ) HAMISH HAMILTON ( THE PALE KING THE PALE IMAGE FROM THE COVER OF DAVID FOSTER WALLACE'S NEW NOVEL FOSTER WALLACE'S IMAGE FROM THE COVER OF DAVID David Foster Wallace's final novel p 8 Highlights of April book, CD & DVD new releases. More inside. FICTION AUS FICTION BIOGRAPHY CRIME FICTION DVD POP CD CLASSICAL FICTION $29.99 $24.95 $32.95. $32.95 $20.95 $39.95. $29.95 $24.95 $59.95 $33.95 >> p5 Ebook $18.99 >> p11 $32.95 $27.95 >> p8 >> p16 >> p17 >> p19 >> p4 >> p10 April event highlights : Andrew Fowler on Wikileaks, Betty Churcher on Notebooks, Julian Burnside talks to Michael Kirby. More events inside. All shops open 7 days, except State Library shop, which is open Monday - Saturday. Carlton 309 Lygon St 9347 6633 Hawthorn 701 Glenferrie Rd 9819 1917 Malvern 185 Glenferrie Rd 9509 1952 Port Melbourne 253 Bay St 9681 9255 St Kilda 112 Acland St 9525 3852 Readings at the State Library of Victoria 328 Swanston St 8664 7540 email us at [email protected] Browse and buy online at www.readings.com.au and at ebooks.readings.com.au EBOOK ALSO AVAILABLE NOW FROM www.ebooks.readings.com.au 2 Readings Monthly April 2011 ORANGE LONGLIST Almost half of the writers on this year’s longlist for the Orange Prize for Fiction are Meet the bookseller debut novelists – providing plenty of op- with … portunities for award followers to discover Fiona Hardy, Readings Carlton This Month’s News new favourites. -

Mike Carlton on the ABC of the Attendance by ABC Advisory and ABC Board Members

Friends of the ABC (NSW) Inc. quarterly newsletter December 2011 UPDATE Vol 19, No. 4 incorporating Background Briefi ng friends of the abc ABC BOARD AND MANAGEMENT IS DESTROYING THE ABC’S CREATIVE INDEPENDENCE sought. We are about to lose our utilised. The ABC does not pay state Quentin Dempster specialist expertise in arts coverage. payroll tax or company tax and has a Host of 7.30 NSW, Leaked documents indicate that clear operating cost advantage over the distinguished ABC outsourced programming can be commercials because of this. The ABC journalist very expensive, particularly where does not pay an effi ciency dividend. outside production companies The strategy of the current ABC board have negotiating leverage, which and management is destructive of the Quentin Dempster, presenter of 7.30 consequently leaves the ABC with no ABC’s creative independence. The NSW and courageous spokesperson IP – intellectual property – or archive. only hope we have to restore that for ABC staff, responds to the The ABC has made itself entirely creative independence is through the recently released report of the Senate dependent on the commercial current convergence review where the Inquiry into ABC Television. television production sector adequacy of funding for the broadcaster I’ve read the report and it fi nds that for almost all its non-news can be confronted. the concerns of ABC staff and the programming. Friends about dismantling the skills This is a strategic mistake which base within ABC television production over time will add to our costs. are justifi ed. Neither the MD nor the Director of The distressing aspect of all this is Television produced any rebuttal Inside that the ABC has ignored the inquiry’s evidence to submissions that it fi ndings. -

Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia

Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia Edited by Halim Rane Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia Editor Halim Rane MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editor Halim Rane Centre for Social and Cultural Research / School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science Griffith University Nathan Australia Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) (available at: www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/ Australia muslim). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Volume Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-0365-1222-8 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-0365-1223-5 (PDF) © 2021 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Editor .............................................. vii Preface to ”Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia” ........................ ix Halim Rane Introduction to the Special Issue “Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia” Reprinted from: Religions 2021, 12, 314, doi:10.3390/rel12050314 .................. -

UNAA Media Award Winners and Finalists

UNAA Media Award Winners and Finalists 2018_____________________________________________ Outstanding Contribution to Humanitarian Journalism: Michael Gordon Promotion of Empowerment of Older People (sponsored by Cbus) WINNER: Japan's Cheerleading Grannies, Dean Cornish and Joel Tozer, Dateline, SBS FINALIST: I Speak Your Language, Stefan Armbruster, SBS World News FINALIST: 40 years fighting for freedom, Patrick Abboud, SBS Promotion of Social Cohesion WINNER: Rough Justice: a new future for our youth? Jane Bardon and Owain Stia-James, ABC News FINALIST: Seeds of Change, Compass, Kim Akhurst, Mark Webb, Philippa Byers, Jessica Douglas-Henry, Richard Corfield, ABC FINALIST: We don’t belong to anywhere, Nicole Curby, ABC Radio National FINALIST: Hear Me Out, ABC News Story Lab Promotion of Gender Equality: Empowerment of Women and Girls WINNER: The Justice Principle, Belinda Hawkins, Sarah Farnsworth, Mark Farnell and Peter Lewis, Australian Story, ABC FINALIST: Strong Woman, NITV Living Black FINALIST: The scandal of Emil Shawky Gayed: gynaecologist whose mutilation of women went unchecked for years, Melissa Davey, Carly Earl, Guardian Australia FINALIST: The Matildas: Pitch Perfect, Jennifer Feller, Garth Thomas, Camera-Quentin Davis,Ron Ekkel, Anthony Frisina, Stuart Thorne, Australian Story, ABC Promotion of Empowerment of Children and Young People WINNER: Speak even if your voice shakes, Waleed Aly, Tom Whitty and Kate Goulopoulos, The Project FINALIST: Rough Justice: a new future for our youth? Jane Bardon and Owain Stia-James, ABC -

Australian Muslim Leaders, Normalisaton and Social Integration

AUSTRALIAN MUSLIM LEADERS, NORMALISATON AND SOCIAL INTEGRATION Mohammad Hadi Sohrabi Haghighat Thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2013 Swinburne University ABSTRACT Functionalism has been the dominant framework for the explanation of social integration. Policies for the integration of migrants in the West have mainly centred on the improvement of migrants’ socio-economic situation (employment, education and income). Nonetheless, for Muslim minorities in the West, including Australia, the functionalist conception of integration is inadequate. Although Muslim minorities are socio- economically disadvantaged, they are also subject to social exclusion based on their religion and culture. This is due to a longstanding historical ideological construction of Islam as stagnant, pre-modern, despotic, patriarchal and violent, in opposition to the progressive, modern, democratic, egalitarian and civilised West. This is to say that Muslims have been placed outside the space of ‘normal’ in western discourses. Muslims will not be able to fully integrate into Australian society unless their derogatory image changes. This study aims to explore the issue of social integration from the perspective of Australian Muslim leaders. It is argued that social integration can be defined as a process of normalisation. ‘Integrationist’ Muslim leaders struggle to normalise the image of Muslims and Islam in the Australian public sphere. Their efforts have both organisational and discursive aspects. This process of normalisation, however, is contested from both within and without. From within, there are Muslim ‘radicals’ and ‘isolationists’ who challenge the normalisation process. From without, the media’s disproportionate focus on provocative and radical Muslim voices challenges the integrationist leaders’ efforts. -

BAR NEWS 2019 - AUTUMN.Pdf

THE JOURNAL OF THE NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | AUTUMN 2019 barTHE JOURNAL OFnews THE NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | AUTUMN 2019 WE ARE THE BAR A special edition on diversity at the NSW Bar ALSO Interview with The Hon Margaret Beazley AO QC news An autopsy of the NSW coronial system THE JOURNAL OF NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | AUTUMN 2019 bar CONTENTS THE JOURNAL OF THE NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | AUTUMN 2019 02 EDITOR’S NOTE barnews 04 PRESIDENT’S COLUMN 06 OPINION The Bar under stress EDITORIAL COMMITTEE A three-cavity autopsy of the NSW coronial system: what's going on inside? Ingmar Taylor SC (Chair) news Gail Furness SC An ambitious water plan fails to deliver Anthony Cheshire SC Farid Assaf SC Clickwrap contracts Dominic Villa SC THE JOURNAL OF NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | AUTUMN 2019 18 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS Penny Thew Daniel Klineberg 39 FEATURES Catherine Gleeson bar Lyndelle Barnett Data on diversity: The 2018 Survey Victoria Brigden Juliet Curtin Breaking the culture of silence - sexual harassment at the Bar Kevin Tang Advocates for Change - Jane Needham SC Belinda Baker Stephen Ryan Advocates for Change - Hament Dhanji SC Joe Edwards Bar Association staff members: Advocates for Change - Andrew Pickles SC Michelle Nisbet Race and the Bar Ting Lim, Senior Policy Lawyer ISSN 0817-0002 Disability and the Bar Further statistics on women at the New South Wales Bar Views expressed by contributors to Bar News are not necessarily What is the economic cost of discrimination? those of the New South Wales Bar Association. Parental leave - balancing the scales Contributions are welcome and Working flexibly at the Bar - fact or fiction? should be addressed to the editor: Ingmar Taylor SC Avoiding the law; only to be immersed in it Greenway Chambers L10 99 Elizabeth Street Untethered: ruminations of a common law barrister Sydney 2000 Journey through my lens DX 165 Sydney Contributions may be subject to Socio-economic ‘diversity’ at the New South Wales Bar editing prior to publication, at the Katrina Dawson Award recipients discretion of the editor. -

Annual Report 2016-17 3 Report Report from from Chair Chair

ANNUAL R E P O R T 2016-17 Letter of transmittal Minister for the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 September 2017 Dear Minister, On behalf of the Board of the Australia Council, I am pleased to submit the Australia Council Annual Report for 2016–17. The Board is responsible for the preparation and content of the annual report pursuant to section 46 of the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013, the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 and the Australia Council Act 2013. The following report of operations and financial statements were adopted by resolutions of the Board on 30 August 2017. Yours faithfully, Rupert Myer AO Chair, Australia Council Cover image: Dancenorth - Tectonic, dancers Mason Kelly and Harrison Hall Credit: Amber Haines CONTENTS Report from the Chair 4 Report from the CEO 7 About Australia Council 10 Australia Council Support for the Arts 14 Annual Performance Statements 17 Individual Artists 28 Arts Organisations 34 Small to Medium Arts Organisations 36 Major Performing Arts companies 41 Government Initiatives 44 First Nations Arts 46 Regional Arts 50 International 53 Capacity Building 57 Research and Evaluation 60 Advocacy 63 Co-Investment 65 Our Co-Investment Partners and Projects 68 The Australia Council Board 70 Committees 80 Accountability 86 Freedom of Information 87 External Review 89 Management of Human Resources 90 Ecologically Sustainable Development 93 Organisational Structure 94 Executive Team 95 Financial Statements 96 Compliance Index 142 ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17 3 REPORT REPORT FROM FROM CHAIR CHAIR This Annual Report finds us midway through our Strategic Plan 2014-19 A Culturally Ambitious Nation, which sets out bold aims for the arts in Australia, recognising the unique leadership role the Australia Council plays in building an artistically vibrant arts sector.