Attached Dwellings of Omaha, Nebraska from 1880-1962

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American Resources at History Nebraska

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCES AT HISTORY NEBRASKA History Nebraska 1500 R Street Lincoln, NE 68510 Tel: (402) 471-4751 Fax: (402) 471-8922 Internet: https://history.nebraska.gov/ E-mail: [email protected] ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS RG5440: ADAMS-DOUGLASS-VANDERZEE-MCWILLIAMS FAMILIES. Papers relating to Alice Cox Adams, former slave and adopted sister of Frederick Douglass, and to her descendants: the Adams, McWilliams and related families. Includes correspondence between Alice Adams and Frederick Douglass [copies only]; Alice's autobiographical writings; family correspondence and photographs, reminiscences, genealogies, general family history materials, and clippings. The collection also contains a significant collection of the writings of Ruth Elizabeth Vanderzee McWilliams, and Vanderzee family materials. That the Vanderzees were talented and artistic people is well demonstrated by the collected prose, poetry, music, and artwork of various family members. RG2301: AFRICAN AMERICANS. A collection of miscellaneous photographs of and relating to African Americans in Nebraska. [photographs only] RG4250: AMARANTHUS GRAND CHAPTER OF NEBRASKA EASTERN STAR (OMAHA, NEB.). The Order of the Eastern Star (OES) is the women's auxiliary of the Order of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. Founded on Oct. 15, 1921, the Amaranthus Grand Chapter is affiliated particularly with Prince Hall Masonry, the African American arm of Freemasonry, and has judicial, legislative and executive power over subordinate chapters in Omaha, Lincoln, Hastings, Grand Island, Alliance and South Sioux City. The collection consists of both Grand Chapter records and subordinate chapter records. The Grand Chapter materials include correspondence, financial records, minutes, annual addresses, organizational histories, constitutions and bylaws, and transcripts of oral history interviews with five Chapter members. -

The Omaha Gospel Complex in Historical Perspective

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Summer 2000 The Omaha Gospel Complex In Historical Perspective Tom Jack College of Saint Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Jack, Tom, "The Omaha Gospel Complex In Historical Perspective" (2000). Great Plains Quarterly. 2155. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2155 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE OMAHA GOSPEL COMPLEX IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE TOM]ACK In this article, I document the introduction the music's practitioners, an examination of and development of gospel music within the this genre at the local level will shed insight African-American Christian community of into the development and dissemination of Omaha, Nebraska. The 116 predominantly gospel music on the broader national scale. black congregations in Omaha represent Following an introduction to the gospel twenty-five percent of the churches in a city genre, the character of sacred music in where African-Americans comprise thirteen Omaha's African-American Christian insti percent of the overall population.l Within tutions prior to the appearance of gospel will these institutions the gospel music genre has be examined. Next, the city's male quartet been and continues to be a dynamic reflection practice will be considered. Factors that fa of African-American spiritual values and aes cilitated the adoption of gospel by "main thetic sensibilities. -

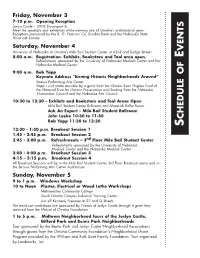

2006 Restore Omaha Program

Friday, November 3 7-10 p.m. Opening Reception Joslyn Castle – 3902 Davenport St. Meet the speakers and exhibitors while viewing one of Omaha’s architectural gems. Reception sponsored by the B. G. Peterson Co, Dundee Bank and the Nebraska State Historical Society Saturday, November 4 VENTS University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Milo Bail Student Center at 62nd and Dodge Streets 8:00 a.m. Registration. Exhibits, Bookstore and Tool area open. E Refreshments sponsored by the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Nebraska Medical Center 9:00 a.m. Bob Yapp Keynote Address “Turning Historic Neighborhoods Around” Strauss Performing Arts Center Yapp’s visit made possible by a grant from the Charles Evan Hughes Fund of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and funding from the Nebraska Humanities Council and the Nebraska Arts Council. 10:30 to 12:30 – Exhibits and Bookstore and Tool Areas Open Milo Bail Student Center Ballroom and Maverick Buffet Room Ask An Expert – Milo Bail Student Ballroom John Leeke 10:30 to 11:30 CHEDULE OF Bob Yapp 11:30 to 12:30 S 12:30 - 1:30 p.m. Breakout Session 1 1:45 - 2:45 p.m. Breakout Session 2 2:45 - 3:00 p.m. Refreshments – 3rd Floor Milo Bail Student Center Refreshments sponsored by the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Nebraska Medical Center 3:00 - 4:00 p.m. Breakout Session 3 4:15 – 5:15 p.m. Breakout Session 4 All Breakout Sessions will be in the Milo Bail Student Center 3rd Floor Breakout rooms and in the Strauss Performing Arts Center Auditorium Sunday, November 5 9 to 1 p.m. -

Lincoln Journal Story on Mildred Brown in 1989

1 “Black-owned paper Thriving after 50 years” Lincoln Journal story on Mildred Brown in 1989 Courtesy of History Nebraska 2 Courtesy of History Nebraska 3 LINCOLN NE, JOURNAL NEBRASKA (page) 31 Mildred Brown runs Omaha Star Black-owned paper thriving after 50 years (Column 1) OMAHA (AP) – An Omaha weekly newspaper founded in 1938 is the country’s longest-operating, black-owned newspaper run by a woman, the newspaper’s founder and publisher said. A pastor in Sioux City, Iowa, first encouraged Mildred Brown more than 50 years ago to start a newspaper geared towards blacks. The ReV. D.H. Harris said, “ ‘Daughter, God told me to tell you to start a paper for these people and bring to them joy and happiness and respect.’ I looked at him and laughed until I cried,” said Brown, of the Omaha Star. The Star is Omaha’s only black-owned newspaper. It first hit the streets on July 9, 1938, with 6,000 copies costing a dime apiece. “It really bothered me,” Brown said of Harris’ adVice. “Then I thought, ‘I’m a young buck. I haVe a car. Every place I went they gave me an ad. I can do it.’ ” The former English teacher had honed her newspaper and ad-selling skills at a Sioux City paper called the Silent Messenger. Moving to Omaha and launching the Star, she said, was a thumbs- up proposition. No front seat By then Brown could run a newspaper, but couldn’t take a front seat on the streetcar or eat at any restaurant she chose. -

Download This

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUM - C 2005 I Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable". For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Race additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets {NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property Historic name Dundee/Happy Hollow Historic District___________________________________ Other names/site number 2. Location Roughly Hamilton on N, JE George & Happy Hollow on W, Street & number Leavenworth on S, 48th on E Not for publication [ ] City or town Omaha Vicinity [] State Nebraska Code NE County Douglas Code 055 Zip code 68132 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this [x] nomination Q request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [x] meets Q does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Omaha, Nebraska, Experienced Urban Uprisings the Safeway and Skaggs in 1966, 1968, and 1969

Nebraska National Guardsmen confront protestors at 24th and Maple Streets in Omaha, July 5, 1966. NSHS RG2467-23 82 • NEBRASKA history THEN THE BURNINGS BEGAN Omaha’s Urban Revolts and the Meaning of Political Violence BY ASHLEY M. HOWARD S UMMER 2017 • 83 “ The Negro in the Midwest feels injustice and discrimination no 1 less painfully because he is a thousand miles from Harlem.” DAVID L. LAWRENCE Introduction National in scope, the commission’s findings n August 2014 many Americans were alarmed offered a groundbreaking mea culpa—albeit one by scenes of fire and destruction following the that reiterated what many black citizens already Ideath of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. knew: despite progressive federal initiatives and Despite the prevalence of violence in American local agitation, long-standing injustices remained history, the protest in this Midwestern suburb numerous and present in every black community. took many by surprise. Several factors had rocked In the aftermath of the Ferguson uprisings, news Americans into a naïve slumber, including the outlets, researchers, and the Justice Department election of the country’s first black president, a arrived at a similar conclusion: Our nation has seemingly genial “don’t-rock-the-boat” Midwestern continued to move towards “two societies, one attitude, and a deep belief that racism was long black, one white—separate and unequal.”3 over. The Ferguson uprising shook many citizens, To understand the complexity of urban white and black, wide awake. uprisings, both then and now, careful attention Nearly fifty years prior, while the streets of must be paid to local incidents and their root Detroit’s black enclave still glowed red from five causes. -

Miscellaneous Collections

Miscellaneous Collections Abbott Dr Property Ownership from OWH morgue files, 1957 Afro-American calendar, 1972 Agricultural Society note pad Agriculture: A Masterly Review of the Wealth, Resources and Possibilities of Nebraska, 1883 Ak-Sar-Ben Banquet Honoring President Theodore Roosevelt, menu and seating chart, 1903 Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation invitations, 1920-1935 Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation Supper invitations, 1985-89 Ak-Sar-Ben Exposition Company President's report, 1929 Ak-Sar-Ben Festival of Alhambra invitation, 1898 Ak-Sar-Ben Horse Racing, promotional material, 1987 Ak-Sar-Ben King and Queen Photo Christmas cards, Ak-Sar-Ben Members Show tickets, 1951 Ak-Sar-Ben Membership cards, 1920-52 Ak-Sar-Ben memo pad, 1962 Ak-Sar-Ben Parking stickers, 1960-1964 Ak-Sar-Ben Racing tickets Ak-Sar-Ben Show posters Al Green's Skyroom menu Alamito Dairy order slips All City Elementary Instrumental Music Concert invitation American Balloon Corps Veterans 43rd Reunion & Homecoming menu, 1974 American Biscuit & Manufacturing Co advertising card American Gramaphone catalogs, 1987-92 American Loan Plan advertising card American News of Books: A Monthly Estimate for Demand of Forthcoming Books, 1948 American Red Cross Citations, 1968-1969 American Red Cross poster, "We Have Helped Have You", 1910 American West: Nebraska (in German), 1874 America's Greatest Hour?, ca. 1944 An Excellent Thanksgiving Proclamation menu, 1899 Angelo's menu Antiquarium Galleries Exhibit Announcements, 1988 Appleby, Agnes & Herman 50 Wedding Anniversary Souvenir pamphlet, 1978 Archbishop -

3.0 Affected Environment and Environmental Consequences of the Alternatives

Proposed Ambulatory Care Center FINAL Environmental Assessment NWIHCS Omaha VAMC January 2018 3.0 Affected Environment and Environmental Consequences of the Alternatives This section discusses environmental considerations for the project, the contextual setting of the affected environment, and impacts of the No-Action Alternative and Proposed Action. Aesthetics Definition of the Resource A visual resource is usually defined as an area of unique beauty that is a result of the combined characteristics of the natural aspects of land and human aspects of land use. Wild and scenic rivers, unique topography, and geologic landforms are examples of the natural aspects of land. Examples of human aspects of land use include scenic highways and historic districts. Visual resources can be regulated by management plans, policies, ordinances, and regulations that determine the types of uses that are allowable or protect specially designated or visually sensitive areas. Affected Environment The Omaha VAMC campus is in an urban setting within the City of Omaha. The campus abuts the Field Club golf course and Field Club Trail on the east, the Douglas County Health Department and Health Center to the north, residences of the Morton Meadows neighborhood on the west, and a major retail and commercial corridor along Center Street to the south including the Hanscom Park neighborhood (see Figure 1-2, also see zoning map Figure 3-6). The Omaha VAMC main campus consists of the main hospital building constructed in approximately 1950, various buildings support buildings, surface parking lots, and green space. Environmental Consequences 3.1.3.1 No-Action Alternative Under the No-Action Alternative, the visual aesthetics at the Omaha VAMC would remain unchanged. -

Omaha Monitor February 10 1917

.~ . .... .: .~' .': ' : .; :.,." .'.. ---HE····,\ONITO- ':-. .' -. ..''~..."l>"'~; ......, :..1'><:'::'::' . .~;. A Natio,rial Weekly Ne," /()...~~ cr Devoted to'the Interests of the Colored ~.~ .• e· :". • ••• ' 10- :., , ... A~f ~~¥ :' .•... '.' .. .' , J ,of Nebraska and the West .'. ::.,." ... '.~ . ~,l~;~V~ ~.': . JOHN· ALBERT WiLLlAMS, Editor 7 .......-.;.,~-~~...,..-.:.:,;.,.,;,.......;.....,.,... ........._--'-~--" '.. P .' . '.. :$~'~50 ~Ye'ar·.· 5C~C9PY. "( '",maha,Neb'raska, Feb. 10, 1917 . Vol. II. No. 33 (Whole No.. 85) .' '. '. ,.I '. ····:'!fblldaOlentalCivit .' . HEY, YOU ' f.ELFOWS;CUT, JT .qUT! . The JuStice of ······~,~:~Riglltsto:Be'G~arded· God hI History ;.~' ~ '" '.' " .' ...-, : '--.' . , ". .. '. ,'. .... '')lhe ·Shifting·6fpopqlati9i,. From •. 1 By the Very Rev, William R. Inge, ",' NOl:tJi' toSouthJ>re~ellts New D.D. .' :. 'p'~obl~iU&~ DE-an of St. Paul's Cathedral, London, . England. .~. "Behold the Lord stood upon a wall ."R()f"'Nasll;JSt~Jl1arh~s' Important riwde by a plumb-line with a plumb , ' . '... Task to b~As~timed.. by the Na line in his hand, "ti~nal: , :.'1"': '.. : . Association.' "And the Lord said unto me: 'Amos, . ". :'.' .:The'ileW,~yearp~e;;entsthe oppor- . ~;::.~ seest thou?' and 1 said, 'A plumb 'tt'init'y o{ageneration for ad"anc~ Ingthestatus9t colored people. Here-:' . "Then said the Lord: 'Behold, I wil1 '. ' . toforethe' dnlyplacewherethe Negl'o . set a plumb-line in the midst of My .' .;.. ,' .... was sure ofidiving,wasfn the South, people, Israel; I will not again pas' . '. b'" them am.' rnoTe..''' .·.whichn9t only pays .twelve or fifteen J . ,doUars~ ;for ,a mont~ in the" cott,on Amos, a keeper of sheep and ~ ·;pr.tCht 1>utthrows in·IYnchings, in-" dresser of vineyards, in the country sultsand disfranchi~eineJit. for.good about Tekoa, was the first of the li~- . ·nie:a~,ui·e.N~w,'how~~er, .a~aresult erary prophets and one of the prd- of,thest9Ppage of immIgration, over foundest moral revealersof any agJ. -

2014 GIVING REPORT It’S No Surprise to Us, Our Donors and the Giving Community Are Among the Most Generous in the Nation - and They Made 2014 an Incrdible Year!

2014 GIVING REPORT It’s no surprise to us, our donors and the giving community are among the most generous in the nation - and they made 2014 an incrdible year! The donors working through the Omaha Community Foundation had a record year. They gave over $173 million to nonprofits which ranked 5th in the nation for most generous among community foundation donors. That level of giving surpassed community foundations in Chicago, New York, and Boston according to the annual report published by CF Insights. Another important milestone for the Foundation was achieved this year. We surpassed $1 billion in assets which make us the 17th largest community foundation nationally. In addition, this was a record year for people joining our family of donors – 159 accounts were opened in 2014. These milestones and record level of growth are important today, but it also means that there will continue to be community investment in our nonprofits long into the future. Our donors love this community and continue to find more ways to make it the best it can be. We exist to help them accomplish those hopes and dreams. Our community’s future is bright. The Omaha Community Foundation connects people who care about our community with the people and nonprofits who are doing the most good here. Over $1.2 billion has been granted to nonprofits on behalf of our donors. And since 1982, our family of over 1,300 donors has given over $1.6 billion to charitable giving accounts at the Omaha Community Foundation. Much has been accomplished, but we are ready to do more. -

2016 GIVING REPORT As We Reflect on the Success of 2016 and Look Ahead, We Are Grateful for the Collective Efforts of All Who Helped Cultivate Generosity This Year

2016 GIVING REPORT As we reflect on the success of 2016 and look ahead, we are grateful for the collective efforts of all who helped cultivate generosity this year. This year our donors gave 11,000 grants—a record!—to 2,349 nonprofits. And we opened 154 new donor accounts, which helps further expand our reach. With more than $1 billion in assets, we are now the 15th largest community foundation in the country, according to CF Insights. While these numbers are impressive, our biggest successes are reflected in the relationships we continue to build across our community. In 2016, we worked to deepen our impact throughout the region. We launched The Landscape, a community indicator project that uses publicly available data to gage how the Omaha metro is faring in six areas community life. This project reaffirms our commitment to meeting the community’s greatest needs, while expanding the breadth and depth of knowledge we offer. The Landscape is a space where each of us can dig deeper and learn about this community beyond our own unique experience; our hope is that this project helps inform our own work, and the efforts of our many partners and collaborators across the Omaha-Council Bluffs region. Each and every day these partners—our board, staff, the area’s nonprofit sector, and our family of donors—are driven to make this community a better place for all. Together we seek to inspire philanthropy that’s both big and small—whether it’s a new $10 donation given during Omaha Gives!, a leader influenced through our Nonprofit Capacity Building Program, or a donor that witnesses the tangible impact of their substantial gift. -

The Fight to Save Jobbers Canyon

“Big, Ugly Red Brick Buildings”: The Fight to Save Jobbers Canyon (Article begins on page 3 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Daniel D Spegel, “ ‘Big, Ugly Red Brick Buildings’: The Fight to Save Jobbers Canyon,” Nebraska History 93 (2012): 54-83 Article Summary: Omaha city leaders touted the Jobbers Canyon warehouse district as a key to downtown redevelopment. But that was before a major employer decided it wanted the land. The ensuing struggle pitted the leverage of a Fortune 500 company against a vision of economic development through historic preservation. The result was the largest-ever demolition of a district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Editor’s Note: Most of the photographs that illustrate this article were shot in the mid-1980s by Lynn Meyer, City of Omaha Planning Department. Cataloging Information: Names: Sam Mercer, Lynn Meyer, James Hanson, Charles M (Mike) Harper, Marty Shukert, Bernie Simon, Harold Andersen, Mark Mercer, George Haecker, Robert Fink, Michael Wiese, Bruce Lauritzen,