The Black Church: a Hegemonic and Counter-Hegemonic Community Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 25B Sfc 20190801 20190801 Abebe Gideon 4 11C Sfc

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY U.S. ARMY HUMAN RESOURCES COMMAND 1600 SPEARHEAD DIVISION AVENUE FORT KNOX, KY 40122 ORDER NO: 203-13 22 Jul 2019 The Secretary of the Army has reposed special trust and confidence in the patriotism, valor, fidelity and professional excellence of the following noncommissioned officers. In view of these qualities and their demonstrated leadership potential and dedicated service to the United States Army, they are, therefore, promoted to the grade of rank shown. Promotion is made in the MOS shown in the name line and the MOS is awarded as his or her primary MOS on the effective date of promotion. Promotion is not valid and will be revoked if the Soldier concerned is not in a promotable status on the effective date of promotion. Acceptance of promotion constitutes acceptance of the 2-year service remaining requirement from the effective date of promotion for Soldiers selected on a FY11 or earlier board, or a 3-year service remaining requirement from the effective date of promotion for Soldiers selected on a FY12 or later board. Soldiers with over 12 years AFS are required to reenlist for indefinite status if they do not have sufficient time remaining to meet this requirement, or decline promotion IAW AR 600-8-19, paragraphs 1-26 and 4-8. The authority for this promotion is AR 600-8-19, paragraph 4-7. Special Instructions: Soldiers promoted to Sergeant Major who do not have USASMC credit are promoted conditionally. Those Soldiers who receive a conditional promotion will be reduced and their names removed from the centralized list if they fail to meet the NCOES requirement. -

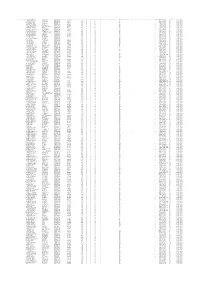

Voter Registration Number Name

VOTER REGISTRATION NUMBER NAME: LAST, FIRST, MIDDLE RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS: FULL STREET RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS: CITY/STATE/ZIP TELEPHONE: FULL NUMBER AGE AT YEAR END PARTY CODE RACE CODE GENDER CODE ETHNICITY CODE STATUS CODE JURISDICTION: MUNICIPAL DISTRICT CODE JURISDICTION: MUNICIPALITY CODE JURISDICTION: SANITATION DISTRICT CODE JURISDICTION: PRECINCT CODE REGISTRATION DATE VOTED METHOD VOTED PARTY CODE ELECTION NAME 141580 ACKISS, FRANCIS PAIGE 2 MULBERRY LN # A NEW BERN, NC 28562 252-671-5911 67 UNA W M NL A RIVE 5 2/25/2015 IN-PERSON UNA 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 140387 ADAMS, CHARLES RAYMOND 4100 HOLLY RIDGE RD NEW BERN, NC 28562 910-232-6063 74 DEM W M NL A TREN 3 10/10/2014 IN-PERSON DEM 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 20141 ADAMS, KAY RUSSELL 3605 BARONS WAY NEW BERN, NC 28562 252-633-2732 66 REP W F NL A TREN 3 5/24/1976 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 157173 ADAMS, LAUREN PAIGE 204 A ST BRIDGETON, NC 28519 252-474-9712 18 DEM W F NL A BRID FC 11 4/21/2017 IN-PERSON DEM 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 20146 ADAMS, LYNN EDWARD JR 3605 BARONS WAY NEW BERN, NC 28562 252-633-2732 69 REP W M NL A TREN 3 3/31/1970 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 66335 ADAMS, TRACY WHITFORD 204 A ST BRIDGETON, NC 28519 252-229-9712 47 REP W F NL A BRID FC 11 4/2/1998 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 49660 ADELSPERGER, ROBERT DEWEY 101 CHADWICK AVE HAVELOCK, NC 28532 252-447-0979 67 REP W M NL A HAVE 2 2/2/1994 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 71341 AGNEW, LYNNE ELIZABETH 31 EASTERN SHORE TOWNHOUSES BRIDGETON, NC 28519 252-638-8302 66 REP W F NL A BRID FC 11 7/27/1999 IN-PERSON -

Esther (Seymour) Atu,Ooa

The Descendants of John G-randerson and Agnes All en (Pulliam,) Se1f11JJ)ur also A Sho-rt Htstory of James Pull tam by Esther (Seymour) Atu,ooa Genealogtcal. Records Commtttee Governor Bradford Chapter Da,u,ghters of Amertcan Bevolutton Danvtlle, Illtnots 1959 - 1960 Mrs. Charles M. Johnson - State Regent Mrs. Richard Thom,pson Jr. - State Chatrman of GenealogtcaJ Records 11rs. Jv!erle s. Randolph - Regent of Governor Bradford Chapter 14rs. Louis Carl Ztllman)Co-Chairmen of Genealogical. Records Corruntttee Mrs. Charles G. Atwood ) .,;.page 1- The Descendants of John Granderson and Agnes Allen (PuJ.liat~) SeymJJur also A Short History of JOJTJSS ...Pall tarn, '1'he beginntng of this genealogy oos compiled by Mrs. Emrra Dora (Mansfield) Lowdermtlk, a great granddaughter of John Granderson ar~ Agnes All en ( Pu.11 iam) SeymJJur.. After the death of }!rs. Lowdermtlk, Hrs. Grace (Roberts) Davenport added, to the recordso With t'he help of vartous JCJ!l,tly heads over a pertod of mcre than three years, I haDe collected and arrari;Jed, the bulk of the data as tt appears in this booklet. Mach credtt ts due 11"'-rs. Guy Martin of Waverly, Illtnots, for long hours spent tn copytn.g record,s for me in. 1°11:organ Oounty Cou,rthou,se 1 and for ,~.,. 1.vorlt in catalogu,tn,g many old country cemetertes where ouP ktn are buried. Esther (SeymDur) Atluooa Typi!IIJ - Courtesy of Charles G. Atwood a,,-.d sec-reta;ry - .l'efrs e El ea?1fJ7' Ann aox. Our earl1est Pulltam ancestora C(]lTl,e from,En,gland to vtrsgtnta, before the middle of the sel)enteenth century. -

Commencement 20-21 Grad List

Northern Essex Community College Commencement 2020-2021 CITY STATE NAME DEGREE Wethersfield CT Sebrina I. Cataldi Associate in Arts General Studies: Individualized Option with High Honors Louisville KY Jessica C. Cunha Associate in Science Business Management Acton MA Michael D. Guarino Associate in Science Computer Information Sciences: Information Technology Option Rafael D. Santos Certificate in Practical Nursing with Honors Agawam MA Natalie Burgos Certificate in Sleep Technologist with Honors Allston MA Hephzibah Frazier Associate in Arts American Sign Language Studies Amesbury MA Melissa R. Barbour Certificate in Peer Recovery Specialist Colette C. Castine Associate in Science Early Childhood Education with High Honors Jennifer D. Collins Certificate in Early Childhood Director with High Honors Noah C. Cotrupi Associate in Arts Liberal Arts with Honors Alexander A. Dannible Associate in Arts Liberal Arts with High Honors Jean M. DesRoches Certificate in Healthcare Technician with Honors Brianna P. Duchemin Associate in Arts General Studies: Art and Design with Honors Graham D. Gannett Associate in Science Business Transfer Glen Gjuraj Associate in Arts General Studies: Art Tyson A. Jackson Associate in Science Business Transfer with Honors Darby J. Jones Associate in Science Biology with Honors Jeanette M. Macomber Associate in Science Human Services with High Honors Sophie H. Rokosz Associate in Science Engineering Science with High Honors Sokunthea Ros Associate in Science Business Transfer with Honors Jonas D. Ruzek Associate in Arts Liberal Arts: Journalism/Communication Option with High Honors Nicole M. Santana- Rivas Associate in Arts Liberal Arts: Psychology Option with Honors Robert G. Schultz Associate in Science Computer Information Sciences: Information Technology Option Dean A. -

Omaha Monitor February 10 1917

.~ . .... .: .~' .': ' : .; :.,." .'.. ---HE····,\ONITO- ':-. .' -. ..''~..."l>"'~; ......, :..1'><:'::'::' . .~;. A Natio,rial Weekly Ne," /()...~~ cr Devoted to'the Interests of the Colored ~.~ .• e· :". • ••• ' 10- :., , ... A~f ~~¥ :' .•... '.' .. .' , J ,of Nebraska and the West .'. ::.,." ... '.~ . ~,l~;~V~ ~.': . JOHN· ALBERT WiLLlAMS, Editor 7 .......-.;.,~-~~...,..-.:.:,;.,.,;,.......;.....,.,... ........._--'-~--" '.. P .' . '.. :$~'~50 ~Ye'ar·.· 5C~C9PY. "( '",maha,Neb'raska, Feb. 10, 1917 . Vol. II. No. 33 (Whole No.. 85) .' '. '. ,.I '. ····:'!fblldaOlentalCivit .' . HEY, YOU ' f.ELFOWS;CUT, JT .qUT! . The JuStice of ······~,~:~Riglltsto:Be'G~arded· God hI History ;.~' ~ '" '.' " .' ...-, : '--.' . , ". .. '. ,'. .... '')lhe ·Shifting·6fpopqlati9i,. From •. 1 By the Very Rev, William R. Inge, ",' NOl:tJi' toSouthJ>re~ellts New D.D. .' :. 'p'~obl~iU&~ DE-an of St. Paul's Cathedral, London, . England. .~. "Behold the Lord stood upon a wall ."R()f"'Nasll;JSt~Jl1arh~s' Important riwde by a plumb-line with a plumb , ' . '... Task to b~As~timed.. by the Na line in his hand, "ti~nal: , :.'1"': '.. : . Association.' "And the Lord said unto me: 'Amos, . ". :'.' .:The'ileW,~yearp~e;;entsthe oppor- . ~;::.~ seest thou?' and 1 said, 'A plumb 'tt'init'y o{ageneration for ad"anc~ Ingthestatus9t colored people. Here-:' . "Then said the Lord: 'Behold, I wil1 '. ' . toforethe' dnlyplacewherethe Negl'o . set a plumb-line in the midst of My .' .;.. ,' .... was sure ofidiving,wasfn the South, people, Israel; I will not again pas' . '. b'" them am.' rnoTe..''' .·.whichn9t only pays .twelve or fifteen J . ,doUars~ ;for ,a mont~ in the" cott,on Amos, a keeper of sheep and ~ ·;pr.tCht 1>utthrows in·IYnchings, in-" dresser of vineyards, in the country sultsand disfranchi~eineJit. for.good about Tekoa, was the first of the li~- . ·nie:a~,ui·e.N~w,'how~~er, .a~aresult erary prophets and one of the prd- of,thest9Ppage of immIgration, over foundest moral revealersof any agJ. -

WNSC Graduate List Includes Cromwell, Ligonier Wawaka High Schools

WNSC Graduate List includes Cromwell, Ligonier Wawaka High Schools Last Name First Name Middle Name Grad Yr Misc Information School Abbott Rebecca 1993 West Noble High School Abbott William Dale 1999 West Noble High School Abdill Edward E 1879 Ligonier Abdill Zulu M 1881 Ligonier Abdullah Salah Ahmed 1999 West Noble High School Abner Brandie Shantelle 2009 West Noble High School Abner Michele Loraine 1994 West Noble High School Abner Tracy 1992 West Noble High School Abrams Delores 1929 Cromwell Abud Tulio Batista 2000 West Noble High School Ackerman Alfred 1921 Ligonier Ackerman Isaac 1883 Ligonier Ackerman Jennie 1888 Ligonier Ackerman Jerry Michael 1993 West Noble High School Ackerman Kevin 1984 West Noble High School Ackerman Shonda 1988 West Noble High School Acosta Angel Clyde 2007 West Noble High School Acosta Ruby Ann 2000 West Noble High School Acosta Zusy Renee 2008 West Noble High School Acton Carrie Anna 1993 West Noble High School Acton James R 1998 West Noble High School Acton Michael Dane 1991 West Noble High School Adair Alice 1967 Cromwell Adair Angela 1983 West Noble High School Adair Beau GJ 2001 West Noble High School Adair Bill 1960 Cromwell Adair Donald 1937 Cromwell Adair Jerod S 1996 West Noble High School Adair Jerry 1964 Wawaka Adair Judy 1961 Cromwell Adair Larry 1964 Wawaka Adair Linda 1964 Cromwell Adair Lois Ellen 1944 Ligonier Adair Matt 1988 West Noble High School Adair Michelle Renee' 1986 West Noble High School Adair Mike 1984 West Noble High School Adair Pam 1984 West Noble High School Adair Patricia -

Infection and Immunity Volume 43 * March 1984 * Number 3 J

INFECTION AND IMMUNITY VOLUME 43 * MARCH 1984 * NUMBER 3 J. W. Shands, Jr., Editor in Chief (1984) University of Florida, Gainesville Phillip J. Baker, Editor (1985) Stephan E. Mergenhagen, Editor (1984) National Institute ofAllergy and Peter F. Bonventre, Editor (1984) National Institute ofDental Research Infectious Diseases University of Cincinnati Bethesda, Md. Bethesda, Md. Cincinnati, Ohio John H. Schwab, Editor (1985) Edwin H. Beachey, Editor (1988) Arthur G. Johnson, Editor (1986) University of North Carolina, VA Medical Center University ofMinnesota, Duluth Medical School Memphis, Tenn. Chapel Hill EDITORIAL BOARD Leonard C. Altman (1986) John C. Feeley (1985) Julius P. Kreier (1986) Stephen W. Russell (1985) Michael A. Apicella (1985) Robert Finberg (1984) Maurice J. Lefford (1984) Catherine Saelinger (1984) Roland Arnold (1984) John R. Finerty (1984) Thomas Lehner (1986) Edward J. St. Martin (1985) Joel B. Baseman (1985) Robert Fitzgerald (1986) Stephan H. Leppla (1985) Irvin E. Salit (1986) Elmer L. Becker (1984) Samuel B. Formal (1986) Michael Loos (1984) Anthony J. Sbarra (1984) Neil Blacklow (1984) John Gallin (1985) John Mansfield (1985) Charles F. Schachtele (1985) Arnold S. Bleiweis (1984) Peter Gemski (1985) Zell A. McGee (1985) Julius Schachter (1986) William H. Bowen (1985) Robert Genco (1985) Jerry R. McGhee (1985) Jerome L. Schulman (1985) Robert R. Brubaker (1986) Ronald J. Gibbons (1985) Douglas D. McGregor (1985) Alan Sher (1984) Ward Bullock, Jr. (1985) Frances Gillin (1984) Floyd C. McIntire (1985) Gerald D. Shockman (1986) Charles Carpenter (1985) Mayer B. Goren (1985) Monte Meltzer (1986) Phillip Smith (1985) Bruce Chassy (1984) Harry Greenberg (1985) Jiri Mestecky (1986) Ralph Snyderman (1985) John 0. -

ANTHEM PARTICIPATING PRIMARY CARE PROVIDER (PCP) LIST - 2020 This List Includes Pcps Who Participate with Anthem BCBS in New Hampshire

ANTHEM PARTICIPATING PRIMARY CARE PROVIDER (PCP) LIST - 2020 This list includes PCPs who participate with Anthem BCBS in New Hampshire. Please note this is not an all-inclusive list for Access Blue New England, BlueChoice New England or HMO Blue New England plans. To search for participating PCPs or providers in other New England states, visit www.healthtrustnh.org and click on the orange Medical icon, then follow the simple instructions located under Medical Plan Provider Directories in the box on the right side of the page. PCP# LAST NAME FIRST NAME TITLE PROVIDER LOCATION/PRACTICE NAME CITY STATE ZIP PHONE PRIMARY SPECIALTY 770YP22529 AAKRE KIMBERLY J MD WINDSOR HOSPITAL CORP WINDSOR VT 05089 (802) 674-7337 PEDIATRICS 770YP22529 AAKRE KIMBERLY J MD WINDSOR HOSPITAL CORP WOODSTOCK VT 05091 (802) 457-3030 PEDIATRICS 770YP34527 ABBOTT CARA L APRN WENTWORTH DOUGLASS PHYSICIAN CORP LEE NH 03861 (603) 868-3300 FAMILY NURSE PRACTITIONERS 770YP30990 ABBOTT MCCALL M APRN CONCORD HOSPITAL INC CONCORD NH 03301 (603) 226-3400 FAMILY NURSE PRACTITIONERS 770YP16108 ABEL SUSAN E MD DARTMOUTH HITCHCOCK CLINIC NASHUA NH 03063 (603) 577-4400 PEDIATRICS 770YP36640 ABELE MICHAEL J MD PARTNERS COMMUNITY PHYS ORGANIZATION INC HAVERHILL MA 01830 (978) 521-3270 INTERNAL MEDICINE 770YP33636 ABEYSINGHE CHAMPA D MD HEALTH FIRST FAMILY CARE CENTER FRANKLIN NH 03235 (603) 934-0177 INTERNAL MEDICINE 770YP33636 ABEYSINGHE CHAMPA D MD HEALTH FIRST FAMILY CARE CENTER LACONIA NH 03246 (603) 366-1070 INTERNAL MEDICINE 770YP05379 ABRAHAM PHILIP MD PHILIP ABRAHAM MD SANFORD -

Jury Convicts Man in Killing

Project1:Layout 1 6/10/2014 1:13 PM Page 1 Olympics: USA men’s boxing has revival in Tokyo /B1 THURSDAY T O D A Y C I T R U S C O U N T Y & n e x t m o r n i n g HIGH 84 Numerous LOW storms. Localized flooding possible. 73 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com AUGUST 5, 2021 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community $1 VOL. 126 ISSUE 302 SO YOU KNOW I The Florida Depart- ment of Health Jury convicts man in killing has ceased the daily COVID-19 re- ports that have been used to track Michael Ball, 64, faces possibility of life in prison for shooting of neighbor changes in the MIKE WRIGHT It’s as simple as prison. Sentenc- video recording of an in- video. “I hate it but he number of corona- Staff writer that,” Ball said. ing was set for terview detectives con- didn’t give me no virus cases and A four-man, Sept. 15. ducted with Ball at the choice.” deaths in the state. A Beverly Hills man on two-woman jury Ball, 64, was county jail after the Ball said he had just trial for second-degree held Ball respon- charged in the shooting. finished cleaning the murder in the shooting sible, convicting March 25, 2020, During the interview, handgun when he stuffed NEWS death of a neighbor said him as charged death of 32-year- Ball repeatedly states he it in his waistband, cov- he was afraid for his life Wednesday eve- old Tyler Dorbert shot Dorbert out of fear ered with a sweatshirt, BRIEFS when he pulled the ning at the conclu- Michael on a street outside based on an assault that and went outside to get trigger. -

THE GETAWAY GIRL: a NOVEL and CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By

THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By EMILY CHRISTINE HOFFMAN Bachelor of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 1999 Master of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2009 THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION Dissertation Approved: Jon Billman Dissertation Adviser Elizabeth Grubgeld Merrall Price Lesley Rimmel Ed Walkiewicz A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to several people for their support, friendship, guidance, and instruction while I have been working toward my PhD. From the English department faculty, I would like to thank Dr. Robert Mayer, whose “Theories of the Novel” seminar has proven instrumental to both the development of The Getaway Girl and the accompanying critical introduction. Dr. Elizabeth Grubgeld wisely recommended I include Elizabeth Bowen’s The House in Paris as part of my modernism reading list. Without my knowledge of that novel, I am not sure how I would have approached The Getaway Girl’s major structural revisions. I have also appreciated the efforts of Dr. William Decker and Dr. Merrall Price, both of whom, in their role as Graduate Program Director, have generously acted as my advocate on multiple occasions. In addition, I appreciate Jon Billman’s willingness to take the daunting role of adviser for an out-of-state student he had never met. Thank you to all the members of my committee—Prof. -

Download 1 File

BREAKING INDIA western Interventions in Dravidian and Dalit Faultlines Rajiv Malhotra & Aravindan Neelakandan Copyright © Infinity Foundation 2011 AU rights reserved. No part of tliis book may be used or reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. Rajiv Malhotra and Aravindan Neelakandan assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work This e<iition first published in 2011 Third impression 2011 AMARYLLIS An imprint of Manjul Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. Editorial Office: J-39, Ground Floor, Jor Bagh Lane, New Delhi-110 003, India Tel: 011-2464 2447/2465 2447 Fax: 011-2462 2448 Email: amaryllis®amaryllis.co.in Website: www.amaryUis.co.in Registered Office: 10, Nishat Colony, Bhopal 462 003, M.P., India ISBN: 978-81-910673-7-8 Typeset in Sabon by Mindways 6esign 1410, Chiranjiv Tower, 43, Nehru Place New Delhi 110 019 ' Printed and Bound in India by Manipal Technologies Ltd., Manipal. Contents Introduction xi 1. Superpower or Balkanized War Zone? 1 2. Overview of European Invention of Races 8 Western Academic Constructions Lead to Violence 8 3. Inventing the Aryan Race 12 Overview of Indian Impact on Europe: From Renaissance to R acism 15 Herder’s Romanticism 18 Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel (1772-1829) 19 ‘Arya’ Becomes a Race in Europe 22 Ernest Renan and the Aryan Christ 23 Friedrich Max Muller 26 Adolphe Pictet 27 Rudolph Friedrich Grau 28 Gobineau and Race Science 29 Aryan Theorists and Eugenics 31 Chamberlain: Aryan-Christian Racism 32 Nazis and After 34 Blaming the Indian Civilization . -

Children > but a for the AMERICANS NOW and ALWAYS Uncle, Long Biter Dose Notice Rest of the Allies

into Africa. The addition of such SKITS OF SOLOMON a distinguished member cannot be dis- Peace counted and we are going to join with him for a more intimate The Monitor acquaintance Germany has kicked over her bucket with our people “away over there.” of militarism and the kaiser has A to the social and interests Weekly Newspaper devoted civic, religious We are anxious to know what are of the Colored People of Nebraska and the Nation, with the desire to con- they hauled it Holland way. Just what be- how are tribute something to the general good and upbuilding of the community and doing, they succeeding and came of Mr. Gott, the kaiser’s side of the race. to them if we can to Your of PUBLISHED EVERY SATURDAY. help and have kick, is difficult to utter. The same Buy Copy them help us if they can. The inter- of uterance is reserved for Entered as Second-Class Mail Matter July 2. 1915, at the Postofflce at difficulty ests of the race the world Omaha. Nieb., under the Act of March 3, 1879. throughout the Clown Quince, who has been re- are the same and a constant THE REV. JOHN ALBERT WILLIAMS, Editor and Publisher. i sympathy ported in the obituary notices seven and mutual cannot Lucille Skaggs Edwards and William Garnett Haynes. Associate Editors. helpfulness do times. Twice more and he’ll have George Wells Parker, Contributing Editor. Bert Patrick, Business aught than make us greater, stronger Manager. Fred C. Williams. Traveling Representative. lives as lengthly as friend cat of the and better.