Minnesota Extreme Heat Toolkit: Definitions and References

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relative Contributions of Temperature and Moisture to Heat Stress

1 The Relative Contributions of Temperature and Moisture to Heat Stress 2 Changes Under Warming ∗ 3 Nicholas J. Lutsko 4 Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA ∗ 5 Corresponding author address: Nicholas Lutsko, [email protected] 6 E-mail: [email protected] Generated using v4.3.2 of the AMS LATEX template 1 ABSTRACT 7 Increases in the severity of heat stress extremes are potentially one of the 8 most impactful consequences of climate change, affecting human comfort, 9 productivity, health and mortality in many places on Earth. Heat stress results 10 from a combination of elevated temperature and humidity, but the relative con- 11 tributions each of these makes to heat stress changes have yet to be quantified. 12 Here, conditions on the baseline specific humidity are derived for when spe- 13 cific humidity changes will dominate heat stress changes (as measured using 14 the equivalent potential temperature, qE), and for when temperature changes 15 will dominate. Separate conditions are derived over ocean and over land, in 16 addition to a condition for when relative humidity changes dominate over the 17 temperature response at fixed relative humidity. These conditions are used to 18 interpret the qE responses in transient warming simulations with an ensemble 19 of models participating in the Sixth Climate Model Intercomparison Project. 20 The regional pattern of qE changes is shown to be largely determined by the 21 pattern of specific humidity changes, with the pattern of temperature changes 22 playing a secondary role. This holds whether considering changes in mean 23 summertime qE or in extreme (98th percentile) qE events. -

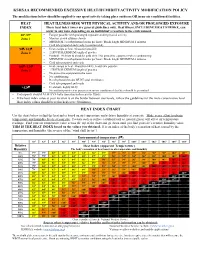

Kshsaa Recommended Excessive Heat/Humidityactivity Modification Policy Heat Index Chart

KSHSAA RECOMMENDED EXCESSIVE HEAT/HUMIDITYACTIVITY MODIFICATION POLICY The modifications below should be applied to any sport/activity taking place outdoors OR in un-air conditioned facilities. HEAT HEAT ILLNESS RISK WITH PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND/OR PROLONGED EXPOSURE INDEX These heat index zones are general guidelines only. Heat illness, INCLUDING HEAT STROKE, can occur in any zone depending on an individual’s reaction to the environment. 80°-89° – Fatigue possible with prolonged exposure and/or physical activity Zone 1 – Monitor at-risk athletes closely – MINIMUM 3 rest/hydration breaks per hour / Break length MINIMUM 4 minutes – Cold tubs prepared and ready (recommended) 90- 103 – Heat cramps or heat exhaustion possible Zone 2 – 2 HOUR MAXIMUM length of practice – Football: Helmets & shoulder pads only / No protective equipment when conditioning – MINIMUM 4 rest/hydration breaks per hour / Break length MINIMUM 4 minutes – Cold tubs prepared and ready 103- 124 – Heat cramps or heat exhaustion likely, heatstroke possible Zone 3 – 1 HOUR MAXIMUM length of practice – No protective equipment to be worn – No conditioning – Rest/hydration breaks MUST total 20 minutes – Cold tubs prepared and ready >124 – Heatstroke highly likely – No outdoor practices or practices in un-air conditioned facilities should be permitted – Participants should ALWAYS have unrestricted access to fluids. – If the heat index value at your location is on the border between two levels, follow the guidelines for the more conservative level. – Heat index values should be rechecked every 30 minutes. HEAT INDEX CHART Use the chart below to find the heat index based on air temperature and relative humidity at your site. -

Wet Bulb Globe Temperature Faqs

3/30/17 3rd Annual Collaborative Solutions for Safety in Sport National Meeting Wet Bulb Globe Temperature FAQs Environmental Monitoring Indices • Wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) • Air temperature • Relative humidity • Sling psychrometer • Heat index • OSHA chart 1 3/30/17 How are they different? Wet Bulb Globe Temperature • Invented in 1950s for the US Army and Marine Corps • Wet Bulb Temperature (Tw) • Humidity, (Wind) • Globe Temperature (Tg) • Solar radiation, (Wind) • Dry Bulb Temperature (Td) • Air temperature WBGT= 0.7Tw + 0.2Tg + 0.1Td Budd GM. Wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT)--its history and its limitations. J Sci Med Sport Sports Med Aust. 2008;11(1):20-32. How are they different? Sling Psychrometer • Two thermometers mounted together in the same device. • Calculates the difference between: • Ambient temperature • Wet-bulb thermometer $50- $100/unit • Measures relative humidity • Allows clinician to then derive heat index 2 3/30/17 How are they different? Heat Index • Heat Index is how hot it feels when relative humidity is factored into the ambient temperature. • Heat Index is created based on shady, light-wind conditions. • Not full sunshine • Not strong-wind • Number may NOT be reliable under extreme heat conditions How are they different? Heat Index • Assumptions of Heat Index • Shaded Football helmet • (full sun can increase Heat Index by 15oF) • 5’7”, 147 lbs • Long pants and short sleeve shirtFootball uniform • Walking at 3 mph High physical demand 3 3/30/17 Why WBGT? • WBGT is a more comprehensive representation of environmental conditions • Solar radiation & wind speed are factored into the equation • Devised to account for physical activity Regional Specificity • Regional specific guideline by Grundstein et al. -

Heat Index Climatology for the North-Central United States

HEAT INDEX CLIMATOLOGY FOR THE NORTH-CENTRAL UNITED STATES Todd Rieck National Weather Service La Crosse, Wisconsin 1. Introduction middle Mississippi River Valleys, and the western Great Lakes. Also, the physiological Heat is an underrated danger, with an response to heat will be briefly investigated, average of 175 Americans losing their lives including a review of how heat acclimatization annually from heat-related causes. According to affects the human body’s biology. This the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, protective biological response is an important from 1979-2003 excessive heat exposure consideration when evaluating the impact of the caused 8,015 deaths in the United States. heat on those that are, or are not, acclimatized During this period, more people died from to the heat. extreme heat than from hurricanes, lightning, tornadoes, and floods combined. In this study, 95°F will be used as the start for the climatological analysis as prolonged Heat kills by taxing the human body beyond exposure to heat this warm increases the risk of its ability to cool itself. Cooling is primarily sunstroke, heat cramps, and heat exhaustion accomplished by the evaporation of perspiration. (Table 1) . How efficiently this process functions is directly related to the amount of water vapor in the air. 2. Data High moisture content reduces the evaporative cooling rate of perspiration, making it difficult for All available weather observations from the the body to maintain a steady and safe internal National Climatic Data Center were used from temperature. One way to measure the 192 locations (Fig. 1), extending from Utah to combined effect of temperature and moisture on Michigan, and from the Canadian-U.S. -

Appendix a Gempak Parameters

GEMPAK Parameters APPENDIX A GEMPAK PARAMETERS This appendix contains a list of the GEMPAK parameters. Algorithms used in computing these parameters are also included. The following constants are used in the computations: KAPPA = Poisson's constant = 2 / 7 G = Gravitational constant = 9.80616 m/sec/sec GAMUSD = Standard atmospheric lapse rate = 6.5 K/km RDGAS = Gas constant for dry air = 287.04 J/K/kg PI = Circumference / diameter = 3.14159265 References for some of the algorithms: Bolton, D., 1980: The computation of equivalent potential temperature., Monthly Weather Review, 108, pp 1046-1053. Miller, R.C., 1972: Notes on Severe Storm Forecasting Procedures of the Air Force Global Weather Central, AWS Tech. Report 200. Wallace, J.M., P.V. Hobbs, 1977: Atmospheric Science, Academic Press, 467 pp. TEMPERATURE PARAMETERS TMPC - Temperature in Celsius TMPF - Temperature in Fahrenheit TMPK - Temperature in Kelvin STHA - Surface potential temperature in Kelvin STHK - Surface potential temperature in Kelvin N-AWIPS 5.6.L User’s Guide A-1 October 2003 GEMPAK Parameters STHC - Surface potential temperature in Celsius STHE - Surface equivalent potential temperature in Kelvin STHS - Surface saturation equivalent pot. temperature in Kelvin THTA - Potential temperature in Kelvin THTK - Potential temperature in Kelvin THTC - Potential temperature in Celsius THTE - Equivalent potential temperature in Kelvin THTS - Saturation equivalent pot. temperature in Kelvin TVRK - Virtual temperature in Kelvin TVRC - Virtual temperature in Celsius TVRF - Virtual -

The Heat Index "Equation" (Or, More Than You Ever Wanted to Know About Heat Index)

SR 90-23 Technical Attachment 7/1/90 The Heat Index "Equation" (or, More Than You Ever Wanted to Know About Heat Index) Lans P. Rothfusz Scientific Services Division NWS Southern Region Headquarters, Fort Worth, TX Now that summer has spread its oppressive ridge over most of the Southern Region, NWS phones are ringing off their hooks with questions about the Heat Index. Many questions regard the actual equation used in calculating the Heat Index. Some callers are satisfied with the response that it is extremely complicated. Some are satisfied with the nomogram (see Attachment 1). But there are a few who will settle for nothing less than the equation itself. No true equation for the Heat Index exists. Heat Index values are derived from a collection of equations that comprise a model. This Technical Attachment presents an equation that approximates the Heat Index and, thus, should satisfy the latter group of callers. The Heat Index (or apparent temperature) is the result of extensive biometeorological studies. The parameters involved in its calculation are shown below (from Steadman, 1979). Each of these parameters can be described by an equation but they are given assumed magnitudes (in parentheses) in order to simplify the model. # Vapor pressure. Ambient vapor pressure of the atmosphere. (1.6 kPa) # Dimensions of a human. Determines the skin's surface area. (5' 7" tall, 147 pounds) # Effective radiation area of skin. A ratio that depends upon skin surface area. (0.80) # Significant diameter of a human. Based on the body's volume and density. (15.3 cm) # Clothing cover. -

Measuring Heat Using Wet Bulb Globe Method

Is the heat index efficient to measure heat stress? A Look into an Alternative Index Vanessa Pearce NWS Wichita Background on Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) • Measures heat stress • Alternative to heat index • Utilized by the military and OSHA for years • Taught to athletic training programs • Provides guidelines especially for active individuals or those working outdoors Wet Bulb Globe Temp vs Heat Index WBGT Heat Index Measured in the sun Measured in the shade Uses temperature Uses relative humidity Uses wind Uses cloud cover Uses sun angle *Scale based on active work. www.weather.gov/ict/WBGT WBGT Project NWS nationwide project proposal Partnership with AccuWeather Enterprise Solutions, Inc. Heat tabletop exercises Local studies of heat parameters Coordination with school officials on heat plans Offices Involved Tulsa Raleigh Burlington Wichita Minneapolis La Crosse Comparative Assessment On-site Surface Study Dam Music Festival 13 heat patients (5 on Friday & 8 on Saturday) Difference surface comparison Surface Temp Wind Heat WBGT (F) speed Index (mph) Asphalt 93 4 98 86 Crowd 96 3 105 85 Dirt/dry 93 4 96 85 grass Green 92 4 90 83 Grass Sand 94 4 95 88 Climate Study with USD 259 Coordinating current heat plan with WBGT Assessing climate conditions from August 15-31 12 year study (2005-2017) At 21Z (preliminary results) 0 days >90 WBGT with max of 87 7 days >105 Heat Index with max of 112 Future Considerations Adjusting scale to make it easier to read Changing name Additional studies – different surfaces, acclimation and lower thresholds -

Humidity and Moisture Presenter Notes

Presenter Notes: Slide 1: Humidity and Moisture Welcome to this distance learning module on Student Notes: Humidity and Moisture. My name is Dale Morris. I’m a meteorologist at the Oklahoma Climate Humidity and Moisture: Survey and work as a program manager in An Introduction for Science Teachers outreach. This module is presented as a service by the Climate Survey for its outreach customers, including participants in EarthStorm. Although this module is designed specifically for science teachers to provide content knowledge about humidity, others may find some use of the materials and lesson which accompany this module. This module should take approximately 20 minutes to complete. Learning Objectives Presenter Notes: Slide 2: Learning Objectives • Describe qualitatively the relationship between temperature and average molecular velocity. By the conclusion of this lesson, you should be Student Notes: able to perform these learning objectives. • Describe the processes of condensation and evaporation. • Describe relative humidity in terms of condensation and evaporation rates. • Recognize the relationships among temperature, relative humidity, and dew point temperature. • Identify examples of real-world applications of humidity. Oklahoma Climatological Survey www.ocs.ou.edu Introduction Presenter Notes: Slide 3: Introduction • Humidity is routinely measured and reported, The relative humidity is typically presented Student Notes: but not well understood during every weather report, which gives an by lay audiences. indication of its importance to the weather • Humidity is critical forecast. However, relative humidity is also a component of weather concept not necessarily well understood by lay forecasts and the water audiences. This lack of understanding is cycle. represented by common questions like: • Humidity is a component Oklahoma Mesonet Station (above) • “The relative humidity is 100%. -

Vocabulary Using Science Words Humidity (Hyoo MI Di Tee) 1

Vocabulary Using Science Words humidity (hyoo MI di tee) 1. If the air has __ humidity, amount of water vapor in water vapor might form dew. the air A. high B. low C. zero 'Sometimes a layer of fog covers the ground in the early morning. It becomes tl'Readlng Check impossible to see very far. Fog can form when the humidity is high. Humidity is the 4. When liquid water changes to water amowlt of water vapor in the air. vapor, it takes in a. oxygen b. heat tl'Readlng Check c. water 2. Humidity is the amount of __ in the air. 5 Humidity depends on temperature. a. fog Warm air is less dense than cool air. This b. ground means warm air can hold more water c. water vapor vapor than cool air. It also explains why fog sometimes forms in the morning. The 2 On a hot day, high humidity can make air cools overnight and can't hold as much you uncomfortable. The heat index water. The water vapor changes into the describes the temperature you actually tiny droplets that make up fog. feel based on the air's humidity. Weather 6 Relative humidity is the percentage forecasters often talk about the heat index. of water vapor in the air compared to the If the heat index is high, you should drink maximum amount the air can hold at a extra water. Some people should stay certain temperature. To understand this, indoors when the heat index is high. think about a glass of water. A glass filled to the top is 100% full. -

Forecasting Excessive Heat Events At

Enhancing Resilience to Heat Extremes: Forecas5ng Excessive Heat Events at Subseasonal Lead Times (Week-2 to 4) Augus&n Vintzileos University oF Maryland – ESSIC/CICS-MD and Jon Go3schalck, Mike Halpert, Adam Allgood NOAA/NWS/NCEP/CPC This study is supported by NOAA grants: NA15OAR4310081 NA14NES4320003 NA16OAR4310147 Outline: • Defining Heat Events • Monitoring/Forecas5ng Heat Events • Preliminary forecast verificaon & mul-model approaches • Real5me Forecas5ng during summer 2016 • Summary and ongoing work Heat kills: Excessive Heat results to more Fatali5es than any other atmospheric hazard: From 1986 to 2015 the annual mean fatalies over the United States: Heat = 130 Flood = 81 Tornado = 70 Lightning = 48 Hurricane = 46 Heat kills: The example oF the July 1995 Heat Event From the NOAA study of the event (published December 1995) The Corn Belt Heat kills: Impacts oF Excessive Heat to Human Health Heat Stroke Heat Exhaustion It occurs when the body becomes unable to control its temperature: the body's Rhabdomyolysis temperature rises rapidly, the sweang mechanism fails, and the body is unable to cool down. When heat stroke Heat Syncope occurs, the body temperature can rise to 106°F or higher within 10 to 15 minutes. Heat Heat Cramps stroke can cause death or permanent disability if emergency treatment is not Heat Rash given. Heat kills: Impacts oF Excessive Heat to Human Health • Human Heat Stroke physiology • Geographical Heat Exhaustion It occurs when the body locaon becomes unable to control its • Urban effect temperature: the body's Rhabdomyolysis temperature rises rapidly, the • Preparedness sweang mechanism fails, • and the body is unable to cool Age down. -

Implementation and Comparison of a Suite of Heat Stress Metrics Within the Community Land Model Version 4.5

Geosci. Model Dev., 8, 151–170, 2015 www.geosci-model-dev.net/8/151/2015/ doi:10.5194/gmd-8-151-2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Implementation and comparison of a suite of heat stress metrics within the Community Land Model version 4.5 J. R. Buzan1,2, K. Oleson3, and M. Huber1,2 1Department of Earth Sciences, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire, USA 2Earth Systems Research Center, Institute for the Study of Earth, Ocean, and Space, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire, USA 3National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado, USA Correspondence to: J. R. Buzan ([email protected]) Received: 21 June 2014 – Published in Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss.: 8 August 2014 Revised: 2 December 2014 – Accepted: 23 December 2014 – Published: 5 February 2015 Abstract. We implement and analyze 13 different metrics culation and the improved wet bulb calculation are ±1.5 ◦C. (4 moist thermodynamic quantities and 9 heat stress metrics) These differences are important due to human responses in the Community Land Model (CLM4.5), the land surface to heat stress being nonlinear. Furthermore, we show heat component of the Community Earth System Model (CESM). stress has unique regional characteristics. Some metrics have We call these routines the HumanIndexMod. We limit the al- a strong dependency on regionally extreme moisture, while gorithms of the HumanIndexMod to meteorological inputs of others have a strong dependency on regionally extreme tem- temperature, moisture, and pressure for their calculation. All perature. metrics assume no direct sunlight exposure. The goal of this project is to implement a common framework for calculating operationally used heat stress metrics, in climate models, of- fline output, and locally sourced weather data sets, with the 1 Introduction intent that the HumanIndexMod may be used with the broad- est of applications. -

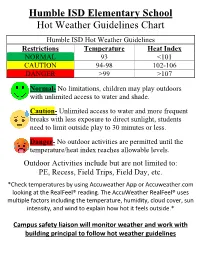

Humble ISD Elementary School Hot Weather Guidelines Chart

Humble ISD Elementary School Hot Weather Guidelines Chart Humble ISD Hot Weather Guidelines Restrictions Temperature Heat Index NORMAL 93 <101 CAUTION 94-98 102-106 DANGER >99 >107 Normal- No limitations, children may play outdoors with unlimited access to water and shade. Caution- Unlimited access to water and more frequent breaks with less exposure to direct sunlight, students need to limit outside play to 30 minutes or less. Danger- No outdoor activities are permitted until the temperature/heat index reaches allowable levels. Outdoor Activities include but are not limited to: PE, Recess, Field Trips, Field Day, etc. *Check temperatures by using Accuweather App or Accuweather.com looking at the RealFeel® reading. The AccuWeather RealFeel® uses multiple factors including the temperature, humidity, cloud cover, sun intensity, and wind to explain how hot it feels outside.* Campus safety liaison will monitor weather and work with building principal to follow hot weather guidelines Humble ISD Middle School Hot Weather Guidelines Chart Humble ISD Hot Weather Guidelines: Outdoor Activities Restrictions Temperature Heat Index Normal 99 <105 Caution 100-102 106-112 Caution With Restrictions 103-105 113-119 Danger 106 >120 Humble ISD Hot Weather Guidelines: Athletic Competitions Restrictions Temperature Heat Index No Restrictions <105 <106 Activity Canceled >106 >120 NORMAL AT A DRY BULB TEMPERATURE OF 99* OR LESS OR A HEAT INDEX OF 105 OR LESS: Normal practice conditions with usual breaks, unlimited access to water. (Usual observations & precautions) CAUTION AT A DRY BULB TEMPERATURE OF 100* - 102* OR A HEAT INDEX OF 106 - 112: Students will continue to be given unlimited access to water and more frequent breaks and less exposure to direct sunlight.