Alcohol Advertising Group Submissions File 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasury Wine Estates Limited – Information Memorandum

Treasury Wine Estates Limited – Information Memorandum In relation to the application for admission of Treasury Wine Estates Limited to the official list of ASX For personal use only Ref:BJ/SM FOST2205-9069112 © Corrs Chambers Westgarth 1 Purpose of Information Memorandum This Information Memorandum has been prepared by Treasury Wine Estates Limited ABN 24 004 373 862 (Treasury Wine Estates) in connection with its application for: (a) admission to the official list of ASX; and (b) Treasury Wine Estates Shares to be granted official quotation on the stock market conducted by ASX. The Information Memorandum will only apply if the Demerger is approved and implemented. This Information Memorandum: • is not a prospectus or disclosure document lodged with ASIC under the Corporations Act; and • does not constitute or contain any offer of Treasury Wine Estates Shares for subscription or purchase or any invitation to subscribe for or buy Treasury Wine Estates Shares. 2 Incorporation of Demerger Scheme Booklet (a) Capitalised terms defined in the Booklet prepared by Foster’s Group Limited ABN 49 007 620 886 (Foster’s) dated 17 March 2011 (a copy of which is included as Appendix 1 to this Information Memorandum) have the same meaning where used in this Information Memorandum (unless the context requires otherwise). (b) The following parts of the Booklet, and any supplementary booklets issued in connection with the Demerger Scheme, are taken to be included in this Information Memorandum: • Important notices and disclaimers, to the extent that it -

Hotel Website Specialists

The on & off Premise Published Bi-annually march 2011 Information about availability of liquor products, CPi eDiTion names of producers and/or distributors, suggested retail prices etc. Hotel Website Specialists • Web Design • Content Management Systems • e-Commerce • Search Engine Optimisation Boylen Media (aha|sa sponsor) Call Tim Boylen on 8233 9433 or email [email protected] LNA0186 0186 LNA TED Liquor Guide 17.3_FA.indd 1 22/02/11 10:00 AM Date: 21/02/2011 Designer: Mike C M Job#/Client: LNA 0186 Trim Size: 210(H) x 297(W)mm Y K Job Name/Ver: TED Liquor Guide 17.03_FA Bleed: 5 mm Index bEER, sTOuT, CiDER, RTD & sOFT DRinK, KEg & glAss PRiCEs .............................................................. 5 bEER – PACKAgED AusTRAliAn from bREWERs ...................................................................................... 6 bEER – PACKAgED inTERnATiOnAl from bREWERs ................................................................................. 7 bEER – PACKAgED AusTRAliAn from MERChAnTs ................................................................................. 7 bEER – PACKAgED inTERnATiOnAl from MERChAnTs ............................................................................ 7 BITTERS........................................................................................................................................................ 10 BOURBON ..................................................................................................................................................... 10 BRANDY -

Financial Services Guide and Independent Expert's Report In

Financial Services Guide and Independent Expert’s Report in relation to the Proposed Demerger of Treasury Wine Estates Limited by Foster’s Group Limited Grant Samuel & Associates Pty Limited (ABN 28 050 036 372) 17 March 2011 GRANT SAMUEL & ASSOCIATES LEVEL 6 1 COLLINS STREET MELBOURNE VIC 3000 T: +61 3 9949 8800 / F: +61 3 99949 8838 www.grantsamuel.com.au Financial Services Guide Grant Samuel & Associates Pty Limited (“Grant Samuel”) holds Australian Financial Services Licence No. 240985 authorising it to provide financial product advice on securities and interests in managed investments schemes to wholesale and retail clients. The Corporations Act, 2001 requires Grant Samuel to provide this Financial Services Guide (“FSG”) in connection with its provision of an independent expert’s report (“Report”) which is included in a document (“Disclosure Document”) provided to members by the company or other entity (“Entity”) for which Grant Samuel prepares the Report. Grant Samuel does not accept instructions from retail clients. Grant Samuel provides no financial services directly to retail clients and receives no remuneration from retail clients for financial services. Grant Samuel does not provide any personal retail financial product advice to retail investors nor does it provide market-related advice to retail investors. When providing Reports, Grant Samuel’s client is the Entity to which it provides the Report. Grant Samuel receives its remuneration from the Entity. In respect of the Report in relation to the proposed demerger of Treasury Wine Estates Limited by Foster’s Group Limited (“Foster’s”) (“the Foster’s Report”), Grant Samuel will receive a fixed fee of $700,000 plus reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses for the preparation of the Report (as stated in Section 8.3 of the Foster’s Report). -

Nutritional Information

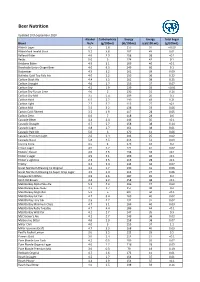

Beer Nutrition Updated 10th September 2020 Alcohol Carbohydrate Energy Energy Total Sugar Brand %v/v (g/100mL) (kJ/100mL) (cal/100 mL) (g/100mL) Abbots Lager 4.5 2.8 155 37 <0.20 Abbotsford Invalid Stout 5.2 3.8 187 45 0.01 Ballarat Bitter 4.6 2.9 158 38 <0.1 Becks 5.0 3 174 42 0.1 Brisbane Bitter 4.9 3.1 169 40 <0.1 Brookvale Union Ginger Beer 4.0 9.3 249 60 9.1 Budweiser 4.5 3.2 161 39 0.09 Bulimba Gold Top Pale Ale 4.0 3.2 150 36 0.22 Carlton Black Ale 4.4 3.3 161 38 0.25 Carlton Draught 4.6 2.7 155 37 0.07 Carlton Dry 4.5 1.9 139 33 <0.01 Carlton Dry Fusion Lime 4.0 2 130 31 0.16 Carlton Dry Mid 3.5 1.4 109 26 0.1 Carlton Hard 6.5 2.7 199 48 0.21 Carlton Light 2.7 2.7 113 27 <0.1 Carlton Mid 3.5 3.2 138 33 0.06 Carton Cold Filtered 3.5 1.9 117 28 0.05 Carlton Zero 0.0 7 118 28 0.6 Cascade Bitter 4.4 2.4 146 35 <0.1 Cascade Draught 4.7 2.7 158 38 0.14 Cascade Lager 4.8 2.7 161 38 0.01 Cascade Pale Ale 5.0 3 170 41 0.06 Cascade Premium Light 2.6 2.4 103 25 0.02 Cascade Stout 5.8 4.5 213 51 0.03 Corona Extra 4.5 4 176 42 0.2 Crown Lager 4.9 3.2 171 41 0.02 Fosters' Classic 4.0 2.5 138 33 <0.1 Foster's Lager 4.9 3.1 169 40 <0.1 Foster's Light Ice 2.3 3.5 116 28 <0.1 Frothy 4.2 2.4 143 34 0.07 Great Northern Brewing Co Original 4.2 1.7 130 31 0.06 Great Northern Brewing Co Super Crisp Lager 3.5 1.4 112 27 0.06 Hoegaarden White 4.9 3.6 187 45 0.2 Kent Old Brown 4.4 3.2 158 38 <0.1 Matilda Bay Alpha Pale Ale 5.2 4.3 196 47 0.03 Matilda Bay Beez Neez 4.7 2.7 157 38 0.2 Matilda Bay Dogbolter 5.2 5 207 50 <0.1 Matilda Bay Fat Yak 4.7 3.4 169 -

Beer Nutrition

Beer Nutrition Updated 6th August 2019 Alcohol Carbohydrate Energy Energy Total Sugar Brand %v/v (g/100mL) (kJ/100mL) (cal/100 mL) (g/100mL) Abbots Lager 4.5 2.8 155 37 <0.20 Abbotsford Invalid Stout 5.2 3.8 187 45 0.01 Ballarat Bitter 4.6 2.9 158 38 <0.1 Becks 5.0 3 174 42 0.1 Brisbane Bitter 4.9 3.1 169 40 <0.1 Brookvale Union Ginger Beer 4.0 9.3 249 60 9.1 Budweiser 4.5 3.2 161 39 0.09 Bulimba Gold Top Pale Ale 4.0 3.2 150 36 0.22 Carlton Black Ale 4.4 3.3 161 38 0.25 Carlton Draught 4.6 2.7 155 37 0.07 Carlton Dry 4.5 1.9 139 33 <0.01 Carlton Dry Fusion Lime 4.0 2 130 31 0.16 Carlton Dry Mid 3.5 1.4 109 26 0.1 Carlton Hard 6.5 2.7 199 48 0.21 Carlton Light 2.7 2.7 113 27 <0.1 Carlton Mid 3.5 3.2 138 33 0.06 Carton Cold Filtered 3.5 1.9 117 28 0.05 Carlton Zero 0.0 7 118 28 0.6 Cascade Bitter 4.4 2.4 146 35 <0.1 Cascade Draught 4.7 2.7 158 38 0.14 Cascade Lager 4.8 2.7 161 38 0.01 Cascade Pale Ale 5.0 3 170 41 0.06 Cascade Premium Light 2.6 2.4 103 25 0.02 Cascade Stout 5.8 4.5 213 51 0.03 Corona Extra 4.5 4 176 42 0.2 Crown Lager 4.9 3.2 171 41 0.02 Fosters' Classic 4.0 2.5 138 33 <0.1 Foster's Lager 4.9 3.1 169 40 <0.1 Foster's Light Ice 2.3 3.5 116 28 <0.1 Frothy 4.2 2.4 143 34 0.07 Great Northern Brewing Co Original 4.2 1.7 130 31 0.06 Great Northern Brewing Co Super Crisp Lager 3.5 1.4 112 27 0.06 Hoegaarden White 4.9 3.6 187 45 0.2 Kent Old Brown 4.4 3.2 158 38 <0.1 Matilda Bay Alpha Pale Ale 5.2 4.3 196 47 0.03 Matilda Bay Beez Neez 4.7 2.7 157 38 0.2 Matilda Bay Dogbolter 5.2 5 207 50 <0.1 Matilda Bay Fat Yak 4.7 3.4 169 40 -

In This ISSUE... China's Property Market, on Which

ISSUE 319a | 30 APRIL–6 MAY 2011 CONTENTs IN THis issue... STOCK REVIEWS STOCK ASX CODE RecoMMENdaTioN PAGE APN News & Media APN Coverage Ceased 6 Nathan Bell CFA Fairfax Media FXJ Coverage Ceased 6 China’s property market, on which Australia’s resource sector, Foster’s Group FGL Hold 7 exports and strong currency rests, appears more bubble than West Aust. Newspaper WAN Coverage Ceased 6 supercycle... (see page 2) stock UPDAtes ANZ Bank ANZ Sell 9 Aristocrat Leisure ALL Buy 9 Carnavon Petroleum CVN Speculative Buy 10 Gaurav Sodhi Computershare CPU Hold 10 Why, in the midst of the greatest commodities boom in history, do Westpac Bank WBC Hold 10 we have only a handful of positive resource stock recommendations? feAtuRES Gaurav Sodhi explains... (see page 4) Director’s Cut: Chinese bubble trouble 2 The commodities conundrum 4 Notes from the Berkshire Hathaway 2011 annual meeting 11 Nathan Bell CFA extRAS The newspaper industry is shrinking into decline. Despite Blog site links 12 newspaper stocks suffering large share price falls recently, value Podcast links 12 remains elusive... (see page 6) Twitter site links 13 Ask the Experts Q&A 13 Important information 14 Gareth Brown RecomMenDATIon chAnges The demerger is good news for Foster’s beer business. But there Aristocrat Leisure upgraded from Long Term Buy to Buy are some looming threats to its incredible margins... (see page 6) PORTFOLIO CHANGES There are no recent portfolio transactions Greg Hoffman Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger provided plenty of food for thought for Australian investors at the weekend. Early on Buffett mentioned that Berkshire had made around $100m on foreign exchange transactions in 2010 in just two currencies.. -

Product-List-July2021.Pdf

Gateway Liquor Wholesalers CODE DESCRIPTION SIZE Beer Craft 1403439 4 PINES BREWING AMERICAN AMBER ALE 24PK 330 1404555 4 PINES BREWING EXTRA REFRESHING ALE 24P 330 1403429 4 PINES BREWING KOLSCH 24PK 330 1403430 4 PINES BREWING PALE ALE 24PK 330 1403585 4 PINES INDIAN SUMMER PALE ALE 24PK 375 1403458 4 PINES PACIFIC ALE 24PK 330 1305835 4 PINES STOUT 24PK 330 1401132 ATOMIC IPA 4X6PK CAN 330 1401131 ATOMIC PALE ALE 4X6PK CAN 330 1401133 ATOMIC XPA 4X6PK CAN 330 1400166 BALTER CAPTAIN SENSIBLE CANS 16PK 375 1400156 BALTER IPA CANS 16PK 375 1403489 BALTER LAGER CANS 16PK 375 1403490 BALTER XPA CANS 16PK 375 1403428 BROOKVALE UNION GINGER BEER 12PK 500 1403469 BROOKVALE UNION GINGER BEER CANS 4X6PK 330 1403470 BROOKVALE UNION SPICED RUM & GINGER 24PK 330 1403656 CAPITAL BREWING COAST ALE CANS 6X4PK 375 1403767 CAPITAL BREWING EVIL EYE IPA 6X4PK CAN 375 1403779 CAPITAL BREWING ROCK HOPPER IPA 24PK CAN 375 1403799 CAPITAL BREWING SUMMIT SESSION ALE 4X4PK 375 1403766 CAPITAL BREWING TRAIL PALE ALE 6X4PK CAN 375 1403886 CAPITAL BREWING XPA CANS 4X4PK 375 100528 DOSS BLOCKOS MERRY JANE PINEAPPLE CAN 24 375 1400087 FERAL BIGGIE JUICE IPA CAN 16PK 375 1400088 FERAL HOP HOG AMERICAN IPA 4X4PK 330 7003001 FOX HAT FULL MONGREL 4PK CANS 375 7003002 FOX HAT PHAT MONGREL 6.50% STOUT CANS 375 1306175 FURPHY BOTTLES 24PK 375 1306188 FURPHY CANS 24PK 375 1401046 GAGE ROADS LITTLE DOVE PALE ALE CAN 24PK 330 1401096 GAGE ROADS PIPE DREAMS COAST LAGER 4X6PK 330 1401164 GAGE ROADS SIDETRACK XPA 3.5% CAN 4X6PK 330 1401034 GAGE ROADS SINGLE FIN BOTTLES 4X6PK -

Scheme of Arrangement (Scheme) and Interconditional Capital Return (Capital Return) (Together, the Transaction)

27 October 2011 RELEASE OF EXPLANATORY BOOKLET Foster’s announces today that the Australian Securities and Investments Commission has registered the Explanatory Booklet in relation to the previously announced scheme of arrangement (Scheme) and interconditional capital return (Capital Return) (together, the Transaction). Printed copies of the Explanatory Booklet, including an independent expert's report, will be mailed to Foster's shareholders over the next week. A copy of the Explanatory Booklet, including the independent expert's report, is attached to this announcement. The Board of Foster’s unanimously recommends that Foster’s shareholders vote in favour of both the Scheme and the Capital Return at the shareholder meetings to be held on 1 December 2011, in the absence of a superior proposal. Subject to those same qualifications, each Director of Foster’s intends to vote all the Foster’s shares held or controlled by them in favour of the Scheme and the Capital Return at the shareholder meetings. Furthermore, the Independent Expert, Grant Samuel, has concluded that the Transaction is fair and reasonable, and in the best interests of Foster’s shareholders. The Independent Expert has assessed the full underlying value of Foster’s at between $5.17 and $5.70 per fully paid share. The Scheme and Capital Return consideration of $5.40 per fully paid share falls well within this range. If you have any questions in relation to the Scheme or the Capital Return, or the Explanatory Booklet, please contact the Foster’s shareholder information line on 1300 048 608 (within Australia) or +61 3 9415 4812 (international) on Business Days between 9.00am and 5.00pm (Melbourne time). -

Beer Cider Spirits

55 workers at the Carlton & United Breweries (C.U.B) were sacked and offered their jobs back for 65% less pay. Aussies across the country are saying enough is enough to corporate greed. No more outsourcing and tax dodging at the expense of our job security and living standards. BEER Fosters Lager Pilsner Urquell Mercury Hard Fosters Light Ice Powers Gold Strongbow Crisp Apple Abbotsford Invalid Stout Great Northern Pure Blonde Strongbow Low Carb Beck’s Premium Mid Hoegaarden Strongbow One Belle-vue Kriek Pure Blonde Leffe Strongbow Dry Budweiser Low Carb Matilda Bay Redds Apple Ale Strongbow Pear Carlton Cold Alpha Pale Ale Reschs Pilsner Strongbow Sweet Apple Carlton Draught Matilda Bay Carlton Dry Beez Neez Reschs Bitter SPIRITS Carlton Dry with Lime Matilda Bay Sheaf Stout Dogbolter Akropolis Oyzo Carlton Mid Stella Artois Matilda Bay Continental Liqueurs Stella Artois Legere Cascade Bitter Fat Yak Cougar Bourbon VB Cascade Blonde Matilda Bay Coyote Tequila Lazy Yak VB Gold Cascade Bright Ale Karloff Vodka Cascade Draught Matilda Bay Yatala Sun Chaser Minimum Chips Prince Albert’s Gin Cascade First Harvest Matilda Bay CIDER Black Douglas Scotch Cascade Pale Ale Redback Whiskey Bulmers Original Cascade Premium Matilda Bay Ruby Tuesday Bulmers Pear Cascade Premium Light Matilda Bay Matilda Bay Cascade Stout The Ducks Dirty Granny Corona Extra Melbourne Bitter Mercury Draught Crown Golden Ale Negra Modelo Mercury Sweet Crown Lager Pacifico Clara Mercury Dry australianunions.org.au/boycott_cub Authorised by Dave Oliver, ACTU Secretary, 365 Queen Street, Melbourne, 3000, VIC ACTU. D No. 119/2016.. -

A Guide to the Alcohol Industry July 2012

A Guide to the Alcohol Industry This document is a guide to the alcohol industry in Australia and how it fits into the global alcohol industry. It outlines the major alcohol companies and the products they produce, own, distribute or market. The information has been collated and summarised from a wide range of sources including alcohol company websites and annual reports. Due to the constantly changing nature of the industry, this document should be taken as a guide only. The information is accurate to the best of our knowledge and we welcome any comments or feedback. We will endeavour to regularly update the information. Abbreviations used: RTD: Ready-To-Drink. Alternative names include alcopops or pre-mixed drinks. RTS: Ready-To-Serve. Last update: 25 July 2012 Compiled by the McCusker Centre for Action on Alcohol and Youth. Please direct comments or feedback to [email protected]. SABMiller The world’s second-largest brewing company, more than 200 beer brands, operating in over 75 countries across six continents. In the year ended 31 March 2011, sold 218 million hectolitres of lager and delivered revenues of US$28,311 million. 14% of global beer sales by volume in 2010 Altria Group (parent company of tobacco company Philip Morris USA) own 27.1% of SABMiller Global headquarters in London, UK MillerCoors (USA) SABMiller Latin America SAB Ltd Joint venture between Miller Brewing Company Operates in 6 countries: Colombia, Ecuador, El and Molson Coors Brewing Company Leading producer and distributer of lager and soft Salvador, -

Hotel Website Specialists

THE ON & OFF PREMISE Published Bi-annually September 2013 Information about availability of liquor products, CPI EDITION names of producers and/or distributors, suggested retail prices etc. Hotel Website Specialists • Web Design • Content Management Systems • e-Commerce • Search Engine Optimisation Boylen Bridgehead (aha|sa sponsor) Call Luke Clayton on 8233 9433 or email [email protected] Our credit manager wears many hats, some of them in the office. Looking after credit management, insurance and legal responsibilities at Samuel Smith & Son, you could say Kathryn Jarrett wears a lot of different hats. But it’s when she’s not at work that she wears most of them. To use her words, Kathryn is ‘‘a passionate horse racing fan’’. She jumps at any chance she has to get glammed up for a jaunt to the track and has an ever-growing collection of fascinating hats to wear for a day at the races. Back in the office though, no matter what hat she’s wearing, Kathryn makes sure that everything runs smoothly. She has been with us for over 18 years now and while she admits it can be a high-pressure job at times, she says it’s the people she works with that have kept her here. ‘‘We have each other’s back and we have a lot of laughs together,’’ says Kathryn. Funnily enough, our long-term clients say our people are the reason why they stick with us too. People, who’ll bend over backwards to make sure that orders are delivered on time. And if that means Kathryn has to stick a couple of boxes in her own car and deliver them on the way home, she’ll put her courier hat on too. -

Hotel Website Specialists

THE ON & OFF PREMISE Published Bi-annually March 2013 Information about availability of liquor products, CPI EDITION names of producers and/or distributors, suggested retail prices etc. Hotel Website Specialists • Web Design • Content Management Systems • e-Commerce • Search Engine Optimisation Boylen Bridgehead (aha|sa sponsor) Call Luke Clayton on 8233 9433 or email [email protected] Index BEER, STOUT, CIDER, RTD & SOFT DRINK, KEG & GLASS PRICES .............................................................. 5 BEER – PACKAGED AUSTRALIAN from BREWERS ...................................................................................... 6 BEER – PACKAGED INTERNATIONAL from BREWERS ................................................................................. 7 BEER – PACKAGED AUSTRALIAN from MERCHANTS ................................................................................. 7 BEER – PACKAGED INTERNATIONAL from MERCHANTS ............................................................................ 8 BITTERS........................................................................................................................................................ 9 BOURBON ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 BRANDY – AUSTRALIAN ................................................................................................................................ 9 PUBLISHING BRANDY – INTERNATIONAL ..........................................................................................................................