Steer: Structural Engineering Extreme Event Reconnaissance Network 2018 HAITI EARTHQUAKE PRELIMINARY VIRTUAL ASSESSMENT TEAM (P-VAT) REPORT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WFP News Video: Haiti November 2019

WFP News Video: Haiti November 2019 Location: Gonaives, Chansolme, Nord-Ouest department, Port au Prince Haiti Shot: 23rd, 25th – 26th, 29th November 2019 TRT: 03:12 Shotlist :00-:07 GV’s trash covered streets in Gonaives. Gonaives, Haiti Shot: 26 Nov 2019 :07-:26 Shots of health centre waiting room. Nutritionist Myriam Dumerjusten attends to 25 year-old mother of four Alectine Michael and checks her youngest child, 8 month-old Jacqueline for malnutrition. Gonaives, Haiti Shot: 26 Nov 2019 :26-:30 SOT Nutritionist Myriam Dumerjusten (French) “It’s a lack of food and a lack of economic means.” Gonaives, Haiti Shot: 26 Nov 2019 :30-:40 A convoy of 9 WFP trucks carry emergency food for a distribution to vulnerable people living in a remote rural area in Haiti Nord-Ouest department. The department is considered one of the most food insecure in the country according to a recent government study. Trucks arrive in Chansolme’s school compound where a large crowd awaits for the food distribution. Nord-Ouest department, Haiti Shot: 23 Nov 2019 :40-:52 Via Cesare Giulio Viola 68/70, 00148 Rome, Italy | T +39 06 65131 F +39 06 6590 632/7 WFP food is off-loaded from the trucks and organised by WFP staff to facilitate the distribution by groups of 4 people. Chansolme, Nord-Ouest department Shot: 23 Nov 2019 :52-1:07 People line up to confirm their ID before distribution. Priority is given to elderly people, pregnant women and handicapped who will be the first in line to receive the food assistance. -

")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un

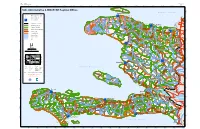

HAITI: 1:900,000 Map No: ADM 012 Stock No: M9K0ADMV0712HAT22R Edition: 2 30' 74°20'0"W 74°10'0"W 74°0'0"W 73°50'0"W 73°40'0"W 73°30'0"W 73°20'0"W 73°10'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°50'0"W 72°40'0"W 72°30'0"W 72°20'0"W 72°10'0"W 72°0'0"W 71°50'0"W 71°40'0"W N o r d O u e s t N " 0 Haiti: Administrative & MINUSTAH Regional Offices ' 0 La Tortue ! ° 0 N 2 " (! 0 ' A t l a n t i c O c e a n 0 ° 0 2 Port de Paix \ Saint Louis du Nord !( BED & Department Capital UN ! )"(!\ (! Paroli !(! Commune Capital (!! ! ! Chansolme (! ! Anse-a-Foleur N ( " Regional Offices 0 UN Le Borgne ' 0 " ! 5 ) ! ° N Jean Rabel " ! (! ( 9 1 0 ' 0 5 ° Mole St Nicolas Bas Limbe 9 International Boundary 1 (!! N o r d O u e s t (!! (!! Department Boundary Bassin Bleu UN Cap Haitian Port Margot!! )"!\ Commune Boundary ( ( Quartier Morin ! N Commune Section Boundary Limbe(! ! ! Fort Liberte " (! Caracol 0 (! ' ! Plaine 0 Bombardopolis ! ! 4 Pilate ° N (! ! ! " ! ( UN ( ! ! Acul du Nord du Nord (! 9 1 0 Primary Road Terrier Rouge ' (! (! \ Baie de Henne Gros Morne Limonade 0 )"(! ! 4 ! ° (! (! 9 Palo Blanco 1 Secondary Road Anse Rouge N o r d ! ! ! Grande ! (! (! (! ! Riviere (! Ferrier ! Milot (! Trou du Nord Perennial River ! (! ! du Nord (! La Branle (!Plaisance ! !! Terre Neuve (! ( Intermittent River Sainte Suzanne (!! Los Arroyos Perches Ouanaminte (!! N Lake ! Dondon ! " 0 (! (! ' ! 0 (! 3 ° N " Marmelade 9 1 0 ! ' 0 Ernnery (!Santiag o \ 3 ! (! ° (! ! Bahon N o r d E s t de la Cruz 9 (! 1 ! LOMA DE UN Gonaives Capotille(! )" ! Vallieres!! CABRERA (!\ (! Saint Raphael ( \ ! Mont -

FY21 Q2 Country Updates

Act to End NTDs | East FY21 Q2 Monthly Updates January 1, 2021–March 31, 2021 Cooperative Agreement No. 7200AA18CA00040 Prepared for Rob Henry, AOR Office of Infectious Diseases U.S. Agency for International Development 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington DC, 20532 Prepared by RTI International 3040 Cornwallis Road Post Office Box 12194 Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-2194 Act to End NTDs | East Program Overview The U.S. Agency for International Development Act to End Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) | East Program supports national NTD programs in reaching World Health Organization goals for NTD control and elimination through proven, cost-effective public health interventions. The Act to End NTDs | East (Act | East) Program also provides critical support to countries on their journey to self-reliance, helping them create sustainable programming for NTD control within robust and resilient health systems. The Act | East Program is being implemented by RTI International with a consortium of partners, led by RTI International and including includes The Carter Center; Fred Hollows Foundation; IMA World Health; Light for the World; Results for Development (R4D); Save the Children; Sightsavers; and Women Influencing Health, Education, and Rule of Law (WI-HER). ii Act | East Country Updates for USAID January–March 2021 January 2021 DRC Act | East Partner: RTI International Total population: 85,281,024 (2018 [est.]) COP: [Redacted] Districts: 519 districts RTI HQ Team: [Redacted] Endemic diseases (# ever endemic districts): Trachoma (65) TABLE: Activities supported by USAID in FY21 Trachoma Mapping Trachoma baseline mapping: 28 EUs, November-January 2021 MDA 1 HZ (Pweto), January 2021 TIS: 1 HZ (Kilwa), October 2020 DSAs (#EUs) TSS: 0 MERLA N/A HSS N/A Summary and explanation of changes made to table above since last month: • None Highlights: • The data for 26 EUs surveyed in the Kasai, Kasai Central, Kwilu and Kwango provinces in December were uploaded to Tropical Data for preliminary analysis and cleaning. -

Flash Appeal Haiti Earthquake

EARTHQUAKE FLASH AUGUST 2021 APPEAL HAITI 01 FLASH APPEAL HAITI EARTHQUAKE This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humani- Get the latest updates tarian Country Team (HCT) and partners. It covers the period from August 2021 to February 2022. OCHA coordinates humanitarian action to ensure On 16 August 2021, a resident clears a home that was damaged during the crisis-affected people receive the assistance and earthquake in the Capicot area in Camp-Perrin in Haiti’s South Department. protection they need. It works to overcome obstacles Photo: UNICEF that impede humanitarian assistance from reaching The designations employed and the presentation of material in the report do not people affected by crises, and provides leadership in imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of mobilizing assistance and resources on behalf of the the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area humanitarian system or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. www.unocha.org/rolac Humanitarian Response aims to be the central website for Information Management tools and services, enabling information exchange between clusters and IASC members operating within a protracted or sudden onset crisis. www.humanitarianresponse.info Humanitarian InSight supports decision-makers by giving them access to key humanitarian data. It provides the latest verified information on needs and delivery of the humanitarian response as well as financial contributions. www.hum-insight.com The Financial Tracking Service (FTS) is the primary provider of continuously updated data on global human- itarian funding, and is a major contributor to strategic decision making by highlighting gaps and priorities, thus contributing to effective, efficient and principled humani- tarian assistance. -

Cholera Treatment Facility Distribution for Haiti

municipalities listed above. listed municipalities H C A D / / O D F I **Box excludes facilities in the in facilities excludes **Box D A du Sud du A S Ile a Vache a Ile Ile a Vache a Ile Anse a pitres a Anse Saint Jean Saint U DOMINICAN REPUBLIC municipalities. Port-au-Prince Port-Salut Operational CTFs : 11 : CTFs Operational Delmas, Gressier, Gressier, Delmas, Pétion- Ville, and and Ville, G Operational CTFs : 13 : CTFs Operational E T I O *Box includes facilities in Carrefour, in facilities includes *Box N G SOUTHEAST U R SOUTH Arniquet A N P Torbeck O H I I T C A I Cote de Fer de Cote N M Bainet R F O Banane Roche A Bateau A Roche Grand Gosier Grand Les Cayes Les Coteaux l *# ! Jacmel *# Chantal T S A E H T U O SOUTHEAST S SOUTHEAST l Port à Piment à Port ! # Sud du Louis Saint Marigot * Jacmel *# Bodarie Belle Anse Belle Fond des Blancs des Fond # Chardonnières # * Aquin H T U O S SOUTH * SOUTH *# Cayes *# *# Anglais Les *# Jacmel de Vallée La Perrin *# Cahouane La Cavaillon Mapou *# Tiburon Marbial Camp Vieux Bourg D'Aquin Bourg Vieux Seguin *# Fond des Negres des Fond du Sud du Maniche Saint Michel Saint Trouin L’Asile Les Irois Les Vialet NIPPES S E P P I NIPPES N Fond Verrettes Fond WEST T S E WEST W St Barthélemy St *# *#*# Kenscoff # *##**# l Grand Goave #Grand #* * *#* ! Petit Goave Petit Beaumont # Miragoane * Baradères Sources Chaudes Sources Malpasse d'Hainault GRAND-ANSE E S N A - D N A R GRAND-ANSE G Petite Riviere de Nippes de Riviere Petite Ile Picoulet Ile Petion-Ville Ile Corny Ile Anse Ganthier Anse-a-Veau Pestel -

HAITI Physical Presence As of 07 October 2019

HAITI Physical presence as of 07 october 2019 This map shows the mapping of humanitarian and development NORD-OUEST NORD NORD-EST actors with a physical presence in ANSE-À-FOLEUR BOMBARDOPOLIS LA TORTUE PORT-DE-PAIX SAINT-LOUIS CAP-HAÏTIEN DONDON MILOT FORT-LIBERTÉ OUANAMINTHE Haiti. It shows the location of their ASA HI ID MFH ACF DU NORD HI COMPASSION Deep Springs CA GRC SJM HAÏTI offices in the different communes. The TF CHANSOLME MÔLE SAINT APRONHA ASA OFASO FAO ICDH WHH ASA CACH LIMONADE PIGNON BASSIN BLEU TF NICOLAS ID PAHO/WHO PAHO/WHO information was collected by OCHA GADEL IOM PWW Haiti Outreach IOM ASA JEAN RABEL PI Haiti via an online survey launched HI MdM-C MFH WVI UNASCAD OXFAM COMPASSION ACF ID UNASCAD in May 2019. PAHO/WHO HLD WHH UNASCAD WVI La Tortue # of 1 - 5 CENTRE organisations 6 - 10 Saint Louis Du Nord BELLADÈRE HINCHE MIREBALAIS NORD-OUEST Port De Paix COMPASSION MPP ACTED per commune Anse A Foleur NORD 11 - 15 Jean Rabel Chansolme FODES-5 PAHO/WHO APADEH Bassin Bleu NORD-EST ICDH UNASCAD Deep Springs Mole Saint Nicolas Cap Haitien 16 - 20 IOM WVI Gros Morne OXFAM LASCAHOBAS SAVANETTE 21 - 35 Bombardopolis Limonade Anse Rouge Milot GRAPDEI ITECA Fort Liberte MdM-Arg Marmelade Ouanaminthe Gonaives Dondon NIPPES ARTIBONITE OUEST ANSE-À-VEAU MIRAGOÂNE ANSE ROUGE GROS-MORNE SAINT-MARC J/P HRO FODES-5 COMPASSION Deep Springs CA ANSE À GALETS GRAND-GOÂVE PORT-AU-PRINCE BARADÈRES TF DESSALINES iTECA ITECA Pignon COMPASSION AQUADEV ACF ASA UNASCAD SCI UEPLM VERRETTES ARTIBONITE SCH WVI ASB ACTED MFH PAILLANT GONAÏVES -

20210505 Sitrep Covid.Pdf (Français)

MINISTERE DE LA SANTE PUBLIQUE ET DE LA POPULATION (MSPP) DIRECTION D'EPIDEMIOLOGIE, DES LABORATOIRES ET DE LA RECHERCHE (DELR) Numéro: 433 05/05/2021 6h00 pm Surveillance de la COVID-19, Haiti, 2020-2021 Au niveau mondial Cas confirmés de COVID-19 par Département et Commune au 5 mai 2021: du 19/03/2020 au 05/05/2021 154,608,198 cas confirmés, dont 3,231,674 décès ont été enregistrés, soit une létalité de 2.1% Source: OMS En Haïti: - 64,755 tests réalisés (138 nouveaux) - 13,227 cas confirmés (17 nouveaux) - 266 décès (0 nouveau) - 12,304 (93%) cas récupérés Létalité: 2.01% -1904 cas hospitalisés (1 nouveau) - De ces 13,227 cas confirmés, 44.24% sont de sexe féminin et 55.76% de sexe masculin Tab.1: Cas confirmés et décès de COVID-19 par département du 19 mars 2020 au 5 mai 2021, Haiti Nouveaux cas Nouveaux décès Département Cas Cumulés. Décès Cumulés Taux de positivité Taux de létalité (24h) (24h) Ouest 9,365 13 121 0 20.2% 1.29% Nord 819 1 38 0 22.5% 4.64% Artibonite 688 0 39 0 23.1% 5.67% Centre 687 0 16 0 27.5% 2.33% Nord-Est 380 0 6 0 11.4% 1.58% Sud-Est 306 0 9 0 27.8% 2.94% Sud 300 0 6 0 23.3% 2.00% Nord-Ouest 284 0 13 0 25.0% 4.58% Grand Anse 237 3 13 0 20.0% 5.49% Nippes 161 0 5 0 19.1% 3.11% Grand Total 13,227 17 266 0 20.6% 2.01% N-B. -

The Haiti Neglected Tropical Diseases (Ntds) Control Program Work Plan and Budget for IMA/RTI Program Year Five October 1, 2010-September 30, 2011

The Haiti Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) Control Program Work Plan and Budget for IMA/RTI Program Year Five October 1, 2010-September 30, 2011 Submitted: August 27, 2010 Table of Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………………………… Page 3 Year Five Program Goals…………………………………………………......... Page 3 Additionality………………………………………………………………….….. Page 4 Mass Drug Administration…………………………………………………….... Page 5 Cost-Efficiencies………………………………………………………………….. Page 6 Post-Elimination Strategies……………….……………………………………… Page 9 Monitoring and Evaluation…………………………………………………....... Page 10 Advocacy…………………………………………………………………………. Page 10 Cost Share……………………………………………………………………....... Page 10 Report Writing…………………………………………………………………… Page 11 Timeline of Major Activities…………………………………………………….. Page 11 Attachment 1: Acronyms………………………………………………………... Page 12 Attachment 2: Scale-up Map…………………………………………………... Page 13 2 1. Executive Summary The Haiti Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) Control Program is a joint effort between the Ministry of Health and Population (MSPP) and the Ministry of Education (MENFP) to eliminate and control Lymphatic Filariasis (LF) and Soil Transmitted Helminthes (STH) in Haiti. The Program is funded by USAID through the Research Triangle Institute (RTI) and by the Gates Foundation through the University of Notre Dame. IMA World Health leads in the implementation of the USAID/RTI funded program activities. The Program is supported by a group of collaborating partners who include World Health Organization/Pan American Health Organization (WHO/PAHO), -

HAITI: 1:250,000 Map No: ADM 001 Stock No: TAHADM250K42X60 0801 HAITI 006O Haiti: Administrative Edition: 6

HAITI: 1:250,000 Map No: ADM 001 Stock No: TAHADM250K42X60_0801_HAITI_006O Haiti: Administrative Edition: 6 74°50'0"W 74°40'0"W 74°30'0"W 74°20'0"W 74°10'0"W 74°0'0"W 73°50'0"W 73°40'0"W 73°30'0"W 73°20'0"W 73°10'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°50'0"W 72°40'0"W 72°30'0"W 72°20'0"W 72°10'0"W 72°0'0"W 71°50'0"W 71°40'0"W 510 520 530 540 550 560 570 580 590 600 610 620 630 640 650 660 670 680 690 700 710 720 730 740 750 760 770 780 790 800 810 820 830 840 850 72°25'0"W 73 74 72°24'0"W 75 7672°23'0"W 77 72°22'0"W78 79 72°21'0"W 780 81 72°20'0"W 82 8372°19'0"W 84 72°18'0"W85 86 72°17'0"W 87 88 72°16'0"W I C m l e Imp Barthelemy p r I c m 7 i y 4 n p r e M r G 1 a e 9 c T Ha r a a m y b p a a a d R r m I o u R re e ue Ra L m 9 is ea TABARRE 9 i TABARRE u s u InsetofPort-au-Prince 0 e R re1 B d u r d d i e ba u S Ta 15 O 22 év ct 22 CITE SOLEIL èr o 1 20 Ov CITE SOLEIL b 2 20 e 20 re barre 20 R Ta e 2ème Mare Rouge R .t CAZEAU Nord Ouest u u e u CARREFOUR CLERCINE H li Place Nègre R p u e R b u 57 e e 57 r O t s R c R La Tortue u a DROUILLARD Ru r u e Seneq ue e eVulc S R a ue i 18°35'0"N R n ou ain Voug C t iller 1ère Pointe des Oiseaux R V Aux Palmistes t Imp e l e 4 D e e my 2 e l r Aux Plaines i leil 9 D e c l r l20 o So 18°35'0"N o Rue u i S 14 il ! l n l I O a ! 20°0'0"N e m ( v r La Tortue u id Rue d Bl e e p R 6 v A Rue Solei Avenue d 1 eSolei m Clercine 16 Des 8 e Ru r i So que le r 1 Indu il lN R. -

Décision Inondations Haiti Nov 2006

COMMISSION EUROPEENNE DIRECTION GENERALE DE L'AIDE HUMANITAIRE - ECHO Décision d'aide humanitaire F9 (FED9) Intitulé: Aide humanitaire en faveur des victimes des inondations de novembre 2006 dans le Nord ouest et le Sud d'Haïti Lieu de l'opération: HAITI Montant de la décision: EUR 1.500.000 Numéro de référence de la décision: ECHO/HTI/EDF/2007/01000 Exposé des motifs 1 - Justification, besoins et population cible : 1.1. - Justification : Depuis le 23 novembre 2006, la République d'Haïti a été touchée par de fortes pluies qui ont causé d’importantes inondations dans les départements du Nord Ouest, des Nippes et de la Grande Anse. Le centre météorologique avait informé les autorités le 22 novembre du passage d’une vague de froid sur le pays et plus particulièrement sur les départements du Sud Est, Sud, Grande Anse, Nippes et Nord Ouest. La vague de froid a en effet causé de nombreux dégâts. Elle est passée sur le pays le 24 novembre, mais les pluies torrentielles ont continué jusqu’au 30 novembre et ont provoqué d’importantes inondations dans les régions indiquées. La Direction Générale de l'Aide Humanitaire (DG ECHO) a été informée de la situation dans le nord ouest par ses partenaires qui travaillent dans cette zone. Des missions d´évaluation ont été effectuées par la Direction de la Protection Civile et par OCHA.1 Trois survols de la zone ont été effectués ainsi que des évaluations de terrain, qui n’ont pas pu être disponibles rapidement du fait des difficultés logistiques pour atteindre les zones affectées, et de leur dispersion géographique. -

Livelihood Profiles in Haiti September 2005 USAID FEWS

Livelihood Profiles in Haiti September 2005 CUBA Voute I Eglise ! 0 2550 6 Aux Plains ! Kilometers Saint Louis du Nord ! Jean Rabel ! NORD-OUEST Beau Champ Mole-Saint-Nicolas ! ! 5 Cap-Haitien (!! 1 Limbe Bombardopolis ! ! Baie-de-Henne Cros Morne !( 2 ! !(! Terrier Rouge ! ! La Plateforme Grande-Riviere !( Plaisance ! 2 du-Nord ! Quanaminthe !(! 7 3 NORD 1 ! Gonaives !( NORD-EST ! Saint-Michel Mont Organise de-lAtalaye ! Pignon 7 ! 2 USAID Dessalines ! ! Cerca Carvajal ARTIBONITE Hinche Petite-Riviere ! Saint-Marc ! !( ! de-LArtibonite Thomassique (! ! ! CENTRE FEWS NET Verrettes Bouli ! La Cayenne Grande Place 4 ! ! ! La Chapelle Etroits 6 1 ! Mirebalais Lascahobas ! ! Nan-Mangot Arcahaie 5 ! ! 3 Seringue Jeremie ! 6 ! (! Roseaux ! Grande Cayemite OUEST Cap Dame-Marie ! Corail ! In collaboration with: ! Port-Au-Prince Pestel ! 2 DOMINICAN ! Anse-a-Veau ^ Anse-DHainault (! ! GRANDE-ANSE ! (! ! ! 6 ! Miragoane 6Henry Petion-Ville Baraderes ! Sources Chaudes Petit-Goave 2 8 NIPPES ! (!! 6 REPUBLIC 5 3 Carrefour Moussignac Lasile ! Trouin Marceline ! ! 3 ! ! Les Anglais Cavaillon Platon Besace Coordination Nationale de la Tiburon ! ! Aquin ! 5 SUD ! Boucan Belier SUD-EST ! Belle-Anse ! 6 ! ! Port-a-Piment 6 1 (!! Jacmel ! ! Thiote Coteaux (!! ! 6 ! 5 Marigot Sécurité Alimentaire du Les Cayes Laborieux 6 2 Bainet Saint-Jean Ile a Vache ! ! ! Port Salut Gouvernement d’Haïti (CNSA) United States Agency for Livelihood Zone International Development/Haiti 1 Dry Agro-pastoral Zone (USAID/Haiti) 2 Plains under Monoculture Zone CARE 3 Humid -

NORD OUEST: 1:100,000 Map No: ADM 006 Stock No: L1K0ADMV0801NOU30R Nord Ouest: Administrative Edition: 3 73°20'0"W 73°10'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°50'0"W 72°40'0"W

NORD OUEST: 1:100,000 Map No: ADM 006 Stock No: L1K0ADMV0801NOU30R Nord Ouest: Administrative Edition: 3 73°20'0"W 73°10'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°50'0"W 72°40'0"W 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 670 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 680 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 690 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 700 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 710 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 720 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 730 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 740 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 750 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 24 24 23 23 23 23 74°0'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°0'0"W Production Date: January 2008 Department Capital 22 \ 22 22 22 (! MINUSTAH GIS Unit Hemboucot Prepared & Printed By: ! ! 20°0'0"N 20°0'0"N ! Port-au-Prince, Haiti ! Petit Paradis Voûte L'Église Atlantic Ocean Bassin Cheval 21 (!! Commune Capital 21 21 21 Contact Details: Any corrections or Claire Messine Dupu!is ! !Clarisse amendments should Tresor 22 ! 22 !Pierre Tules Atlantic Ocean 20 ! Village be addressed to 20 20 20 ! [email protected] ! Gros Raisinier L'Hopital Mor!ne Baranque Servily ! ! Crease ! ! Monder ! ! 2ème Mare Rouge 19 19 N! o Rocrhes Eustachesd 19 O uNan Migoine e s t 19 Embas Morne Gulf of Gonave Mancenillier ! International Boundary µ ! ! Pointe Ouest Boucan Guèpe !Ti Bois Neuf Mare Terrien 19°0'0"N 19°0'0"N ! Savoyard ! !Palan Place Nègre 18 Scale: 1:100,000 18 18 Tête Rochelle! 18 Department Boundary Coordinate System: UTM La Tortue Trou Vasseux ! Saline ! Herbes Marines Projection: Transverse Mercator ! La Vallée Mare Rouge ! ! Mentrie ! Terre Glissée 17 Units: Meters Kilometers Roselière ! 17 Commune Boundary 17 17 ! ! Citron!