Bhavai in Gujrat.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhavai Introduction and History

Paper: 2 Relationship Of Dance And Theatre, Study Of Rupaka And Uparupaka, Traditional Theatres Of India Module 11 Bhavai Introduction And History Bhavai is an extraordinary and unparalleled example of performing arts in Gujarat. It is rich with history, acting, dramatic inspiration and pleasure. There is free flow of the power of imagination. Sharp writing that focuses on important lessons for life revolves around a pithy story. New ideals of youth are chiseled out. Bhavai is an inspiration and holds a mirror to youth. Therefore there is a rationale behind the study of Bhavai. The following is a sketch of the proposed programme: 1) Arrive at fundamental resolutions to discuss how Bhavai can fit into the modern era. 2) Explore the resolutions necessary to accustom to the contemporary era, and where to derive advice and consultations for the same? 3) Brainstorming over means to encourage Bhavai performances. Thinking about solutions like organising competitions, monoacts, and writing on new situations and encouraging other actions on similar thought. 4) To popularise the best Bhavai acts ever staged 5) To think about the possibilities and means by which Bhavai performers can contribute to the Indian governments initiatives, 1 just like people from other professions/disciplines are contributing in their own manner. 6) To organise all Bhavai groups on a common platform 7) To make efforts to address the existential issues of all Bhavai groups 8) To provide systematic training to rising stars of Bhavai so that the art form can exist in the contemporary times. Also for the development of the said artists, make efforts to set up a respective social role so that Bhavai performers as well as the Bhavai genre can prosper and the grand legacy of Bhavai folk art is sustained. -

The Role of Indian Dances on Indian Culture

www.ijemr.net ISSN (ONLINE): 2250-0758, ISSN (PRINT): 2394-6962 Volume-7, Issue-2, March-April 2017 International Journal of Engineering and Management Research Page Number: 550-559 The Role of Indian Dances on Indian Culture Lavanya Rayapureddy1, Ramesh Rayapureddy2 1MBA, I year, Mallareddy Engineering College for WomenMaisammaguda, Dhulapally, Secunderabad, INDIA 2Civil Contractor, Shapoor Nagar, Hyderabad, INDIA ABSTRACT singers in arias. The dancer's gestures mirror the attitudes of Dances in traditional Indian culture permeated all life throughout the visible universe and the human soul. facets of life, but its outstanding function was to give symbolic expression to abstract religious ideas. The close relationship Keywords--Dance, Classical Dance, Indian Culture, between dance and religion began very early in Hindu Wisdom of Vedas, etc. thought, and numerous references to dance include descriptions of its performance in both secular and religious contexts. This combination of religious and secular art is reflected in the field of temple sculpture, where the strictly I. OVERVIEW OF INDIAN CULTURE iconographic representation of deities often appears side-by- AND IMPACT OF DANCES ON INDIAN side with the depiction of secular themes. Dancing, as CULTURE understood in India, is not a mere spectacle or entertainment, but a representation, by means of gestures, of stories of gods and heroes—thus displaying a theme, not the dancer. According to Hindu Mythology, dance is believed Classical dance and theater constituted the exoteric to be a creation of Brahma. It is said that Lord Brahma worldwide counterpart of the esoteric wisdom of the Vedas. inspired the sage Bharat Muni to write the Natyashastra – a The tradition of dance uses the technique of Sanskrit treatise on performing arts. -

Contact: Ketki Parikh 630-964-6061 [email protected] Note: High

Contact: Ketki Parikh 630-964-6061 [email protected] Note: High-resolution photos are available to the media at www.vachikam.org/media FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Updated November 14, 2006 NORTH AMERICAN TOUR OF “KAIFI AUR MAIN” STARRING SHABANA AZMI AND JAVED AKHTAR TO BEGIN NOV. 4 DOWNERS GROVE, ILL.—Internationally acclaimed Indian actress Shabana Azmi and her husband, noted poet and lyricist Javed Akhtar, will bring a very personal story to theatre audiences across the United States and Canada in November and December 2006. This famous duo will be starring in “Kaifi Aur Main,” a theatrical presentation celebrating the life and artistry of progressive Urdu poet and film lyricist Kaifi Azmi as seen through the eyes of his wife, noted actress Shaukat Kaifi. Shabana Azmi, the daughter of Kaifi and Shaukat, will portray her mother on stage, while her husband takes on the role of Kaifi. — MORE — “KAIFI AUR MAIN” ADD ONE Awards Shabana Azmi and Javed Akhtar both have garnered media attention in recent days as the recipients of prestigious awards. On Oct. 26, 2006, Shabana Azmi was presented with the International Gandhi Peace Prize in London for her work as a social activist. She is the first Indian to win this award. On Oct. 31, 2006, Javed Akhtar received the 21st Indira Gandhi Award for National Integration from India’s Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. These awards honor the legacy of Kaifi Azmi and Shaukat Kaifi, who also have been recognized for their contributions to society. Kaifi was a recipient of the prestigious Sahitya Akademi Fellowship, many honorary doctorates from Indian universities, and numerous national awards. -

The Idea of Gujarat History, Ethnography and Text

The Idea of Gujarat History, Ethnography and Text Edited by EDWARD SIMPSON and MARNA KAPADIA ~ Orient BlackSwan THE IDEA OF GUJARAT. ORIENT BLACKSWAN PRIVATE LIMITED Registered Office 3-6-752 Himayatnagar, Hyderabad 500 029 (A.P), India e-mail: [email protected] Other Offices Bangalore, Bhopal, Bhubaneshwar, Chennai, Ernakulam, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Jaipur, Kolkata, ~ . Luoknow, Mumba~ New Delbi, Patna © Orient Blackswan Private Limited First Published 2010 ISBN 978 81 2504113 9 Typeset by Le Studio Graphique, Gurgaon 122 001 in Dante MT Std 11/13 Maps cartographed by Sangam Books (India) Private Limited, Hyderabad Printed at Aegean Offset, Greater Noida Published by Orient Blackswan Private Limited 1 /24 Asaf Ali Road New Delhi 110 002 e-mail: [email protected] . The external boundary and coastline of India as depicted in the'maps in this book are neither correct nor authentic. CONTENTS List of Maps and Figures vii Acknowledgements IX Notes on the Contributors Xl A Note on the Language and Text xiii Introduction 1 The Parable of the Jakhs EDWARD SIMPSON ~\, , Gujarat in Maps 20 MARNA KAPADIA AND EDWARD SIMPSON L Caste in the Judicial Courts of Gujarat, 180(}-60 32 AMruTA SHODaAN L Alexander Forbes and the Making of a Regional History 50 MARNA KAPADIA 3. Making Sense of the History of Kutch 66 EDWARD SIMPSON 4. The Lives of Bahuchara Mata 84 SAMIRA SHEIKH 5. Reflections on Caste in Gujarat 100 HARALD TAMBs-LYCHE 6. The Politics of Land in Post-colonial Gujarat 120 NIKITA SUD 7. From Gandhi to Modi: Ahmedabad, 1915-2007 136 HOWARD SPODEK vi Contents S. -

Gujarati Bhavāi Theatre

P: ISSN NO.: 2394-0344 E: ISSN NO.: 2455 - 0817 Vol-II * Issue-VI* November - 2015 Gujarati Bhavāi Theatre: Today and Tomorrow Abstract Bhavāi, pioneered in the fourteenth century by Asāit Thākar, has been a very popular folk theatre form of Gujarat entertaining and enlightening Gujarati people and incorporating cultural ethos, mythology, folklores, History, dance and music in itself. The paper „Gujarati Bhavāi Theatre: Today and Tomorrow‟ endeavours to study the present scenario of Bhavāi theatre in Gujarat and undertakes to examine issues and challenges of survival and revival of Bhavāi in the age of globalization. While the local issues are more seriously addressed by the elite in the global age, a study of the present state of Bhavāi would be both eye-opening and fruitful. Among the major issues and challenges of Bhavāi include poor financial condition of Bhavāi players, lack of sponsorship, lack of Bhavāi training centres, lack of technology in promotion of Bhavāi, dominance of the main stream Gujarati literature and theatre, popularity of Commercial Theatre in urban areas, influence of television and the Internet, lack of comparative study/research of Bhavāi with other Indian folk theatre forms. The paper also proposes strategies for survival and revival of Bhavāi as the folk theatre form of Gujarat. Developing sense of contribution to the seven hundred years long tradition of Bhavāi, systematic training to Bhavāi players, establishment of Bhavāi Training Centres, introducing Bhavāi to the new generation, inclusion of Bhavāi in the syllabi of literature students, financial support from Corporate Houses, NGOs and State Government are but some of the most significant strategies to be developed for the survival and revival of Bhavāi in the age of globalization. -

Issn 2454-8596 Portrayal of Rural Society in Pannalal

ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- PORTRAYAL OF RURAL SOCIETY IN PANNALAL PATEL’S MANVINI BHAVAI Mr. Nilesh K. Vaja Research Scholar, Dept. of English & CLS, Saurashtra University, Rajkot. Dr. Firoz A Shaikh Associate Professor & Head, Dept. of English, Bhakta Kavi Narsinh Mehta University, Junagadh. Special Issue – I n t e rnational Online Conference Page 1 V o l u m e V I s s u e 5 , M AY - 2020 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract: Pannalal Patel (1912-1989) is an innate and prestigious quality literary artist. His literary work Manvini Bhavai is considered the masterpiece of a regional novel. The translator professor V Y Kantak who translated the novel as Endurance: A Droll Saga in English is an eminent academician and critic, has very successfully retained the essential simplicity, the regional flavor and the original spirit of the novel in English translation as closely as possible. Pannalal‟s sensitive heart comprehends the various experiences of rural life in such a way that we feel human life breathing and beating in a natural way and in his novels. Manvini Bhavai is a great masterpiece of Gujarati literature because of his inborn literary spontaneous talent and potential. He has successfully spread the fragrance of native land in the novel. Each novel of Pannalal is the reflection of society in its naked form and Manvini Bhavai is not an exception. Each chapter of the novel puts a mirror before the society that gives us the exact picture of the time in which it has been penned. -

Situating Right-Wing Interventions in the Bombay Film Industry

Industry Status for Bombay Cinema On 10 May 1998, in an attempt to appease the restive clamour of the film world, industry status was granted to film by the Indian State under the aegis of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led-government, the political arm of the Hindu Right. This decision marked a watershed in the hitherto fraught relations that had existed between the State and Bombay cinema for over fifty years since Independence. Addressing a large gathering of film personalities at a national conference on ‘Challenges Before Indian Cinema’, organised by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry and the Film Federation of India, the Information & Broadcasting (I&B) Minister Sushma Swaraj announced that the ministry would place a proposal in Parliament that would include films in the concurrent list, 1 thereby bringing it within the purview of the central government (‘Industry Status Granted To Film Industry’, 1998). Industry status signified a dramatic shift in State policy towards Hindi cinema as an entertainment industry. Past governments had made empty promises to various industry delegations over the decades that exacerbated tensions between an indifferent and often draconian State and an increasingly anxious industry. So what prompted this decision that led to, ‘the changing relations between the Indian state and Bombay cinema in a global context’ (Mehta 2005: 135) and what was at stake for the right – wing government? And more importantly, what could be the possible implications of this new status on the industry? I hope to answer some of these questions by tracing the process of negotiation initiated from the early 1990s between the Hindu Right (primarily the BJP and the Shiv Sena) and Bombay film industry which, to some extent, may have anticipated the momentous decision of May 1998. -

Issn 2454-859 Issn 2454-8596

ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal HISTROY OF GUJRATI DRAMA (NATAK) Dr. jignesh Upadhyay Government arts and commerce college, Gadhada (Swamina), Botad. Volume.1 Issue 1 August 2015 Page 1 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal HISTROY OF GUJRATI DRAMA (NATAK) The region of Gujarat has a long tradition of folk-theatre, Bhavai, which originated in the 14th-century. Thereafter, in early 16th century, a new element was introduced by Portuguese missionaries, who performed Yesu Mashiha Ka Tamasha, based on the life of Jesus Christ, using the Tamasha folk tradition of Maharashtra, which they imbibed during their work in Goa or Maharashtra.[1] Sanskrit drama was performed in temple and royal courts and temples of Gujarat, it didn't influence the local theatre tradition for the masses. The era of British Raj saw British officials inviting foreign operas and theatre groups to entertain them, this in turn inspired local Parsis to start their own travelling theatre groups, largely performed in Gujarati.[2] The first play published in Gujarati was Laxmi by Dalpatram in 1850, it was inspired by ancient Greek comedy Plutus by Aristophanes.[3] In the year 1852, a Parsi theatre group had performed a Shakespearean play in Gujarati language in the city of Surat. In 1853, Parsee Natak Mandali the first theatre group of Gujarati theatre was founded by Framjee Gustadjee Dalal, which staged the first Parsi-Gujarati play,Rustam Sohrab based on the tale of Rostam and Sohrab part of the 10th-century Persian epicShahnameh by Ferdowsi on 29 October 1853, at at the Grant Road Theatre in Mumbai, this marked the begin of Gujarati theatre. -

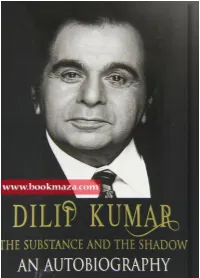

Dilip-Kumar-The-Substance-And-The

No book on Hindi cinema has ever been as keenly anticipated as this one …. With many a delightful nugget, The Substance and the Shadow presents a wide-ranging narrative across of plenty of ground … is a gold mine of information. – Saibal Chatterjee, Tehelka The voice that comes through in this intriguingly titled autobiography is measured, evidently calibrated and impossibly calm… – Madhu Jain, India Today Candid and politically correct in equal measure … – Mint, New Delhi An outstanding book on Dilip and his films … – Free Press Journal, Mumbai Hay House Publishers (India) Pvt. Ltd. Muskaan Complex, Plot No.3, B-2 Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110 070, India Hay House Inc., PO Box 5100, Carlsbad, CA 92018-5100, USA Hay House UK, Ltd., Astley House, 33 Notting Hill Gate, London W11 3JQ, UK Hay House Australia Pty Ltd., 18/36 Ralph St., Alexandria NSW 2015, Australia Hay House SA (Pty) Ltd., PO Box 990, Witkoppen 2068, South Africa Hay House Publishing, Ltd., 17/F, One Hysan Ave., Causeway Bay, Hong Kong Raincoast, 9050 Shaughnessy St., Vancouver, BC V6P 6E5, Canada Email: [email protected] www.hayhouse.co.in Copyright © Dilip Kumar 2014 First reprint 2014 Second reprint 2014 The moral right of the author has been asserted. The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. All photographs used are from the author’s personal collection. All rights reserved. -

^.Internationales Berlin Forum 13.2.-23.2. Des Jungen Films 1982

32.internationale filmfestspiele berlin ^.internationales berlin forum 13.2.-23.2. des jungen films 1982 BHAVNI BHAVAI Inhalt Ein Volksmärchen Das 'Bhavai' ist eine aussterbende Form des Volksdramas im Staate Gujarat, das verschiedene darstellende Künste zu einer sozialen Kommunikationsform verschmilzt. Der Film basiert Land Indien 1981 auf einer solchen alten 'Bhavai'-Erzählung, die von der Aus• beutung der Harijans handelt, der 'Unberührbaren'. In dieser Produktion Sanchar Film Co-operative Society Region erzwangen die höheren Kasten für die Harijans beson• Nehru Foundation dere Kleidungsvorschriften, die diese kennzeichnen und zu• gleich erniedrigen sollten: der Harijan mußte einen Besen hin• ter sich herziehen, der seine Fußspuren verwischte, er hatte sich Regie, Buch Ketan Mehla einen dritten Ärmel als Zeichen der Unterwerfung anzunähen und mußte einen irdenen Spucknapf um den Hals tragen. Kamera Krishnakant 'Pummy' BHAVNI BHAVAI erzählt davon, wie diese erniedrigenden Ton Gujarati sozialen Vorschriften abgeschafft wurden. Einmalig für das Gujarati-Kino ist, daß hier nicht allein das 'Bhavai' als stili• Musik G au ran g Vyas stische Grundlage benutzt, sondern daß auch eine brechtsche Schnitt Ramesh Asher Wendung eingeführt wurde. In dem Film fragt eine verzwei• Künstlerische Leitung Meera I^akhia, felte Gruppe Kinder einen alten Mann, warum ihre Hütten nie• Archana Shah dergebrannt werden. Als Antwort erzählt ihnen der Alte eine Geschichte im 'Bhavai'-Stil. Als der Augenblick der Konfronta• tion zwischen den Harijans und ihren Unterdrückern kommt, Darsteller zeigt er, daß die Unberührbaren in der Lage sind, ihre Angst zu überwinden und um ihre Rechte zu kämpfen. Der König Naseeruddin Shah Ujaam Smita Patil Die Geschichte von BHAVNI BHAVAI hat zwei Ebenen. -

Quest for Excellence

1 Quest for Excellence A biography of Devendra Patel 1 2 Devendra Patel was born on 20 th October 1945 at Bayad, a small town in the district of sabarkantha, Gujarat. His native is Akrund, a small village there. He was born to Gandhian par- ents Jesingbhai Patel and Revaben Patel. His father jesingbhai saw India’s freedom movement from very close and played a major role in his small village too, to free it from the clutches of the landlords and colonial impositions. Akrund was owned by one such Phanse family with such rights, that he freed for the people. Still he had a mutual bond of respect for scholars like Krishna Kumar Phanse from the same family, against whom he fought. He put his one and only son in government primary school to study. To him, the best a father could give his son would be the best possible education. Those days, the newspapers reached the village centers by post the next day. Jesingbhai and others used to go to the school to read newspaper and in- spired his son to read newspapers to keep him aware of the world around. Those days, a new children weekly ‘Zagmag’ was started, that his son fondly liked to read, especially the, characters ‘Chhel ane Chhabo’ ,’Chhako-Mako’ and ‘Mia Fuski and Tabha Bhatt’ created by the writer Jivaram Joshi. By seventh level in school, he started reading mystery stories of N.J. Golibar, detective stories and books like ‘Baraf ni shahjadi’, without the knowledge of his father. In the meantime, a high school was started in a rental house 2 3 there. -

1St Filmfare Awards 1953

FILMFARE NOMINEES AND WINNER FILMFARE NOMINEES AND WINNER................................................................................ 1 1st Filmfare Awards 1953.......................................................................................................... 3 2nd Filmfare Awards 1954......................................................................................................... 3 3rd Filmfare Awards 1955 ......................................................................................................... 4 4th Filmfare Awards 1956.......................................................................................................... 5 5th Filmfare Awards 1957.......................................................................................................... 6 6th Filmfare Awards 1958.......................................................................................................... 7 7th Filmfare Awards 1959.......................................................................................................... 9 8th Filmfare Awards 1960........................................................................................................ 11 9th Filmfare Awards 1961........................................................................................................ 13 10th Filmfare Awards 1962...................................................................................................... 15 11st Filmfare Awards 1963.....................................................................................................