Theory of Quantum Path Entanglement and Interference with Multiplane Diffraction of Classical Light Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31 Diffraction and Interference.Pdf

Diffraction and Interference Figu These expar new .5 wave oday Isaac Newton is most famous for his new v accomplishments in mechanics—his laws of Tmotion and universal gravitation. Early in his career, however, he was most famous for his work on light. Newton pictured light as a beam of ultra-tiny material particles. With this model he could explain reflection as a bouncing of the parti- cles from a surface, and he could explain refraction as the result of deflecting forces from the surface Interference colors. acting on the light particles. In the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- turies, this particle model gave way to a wave model of light because waves could explain not only reflection and refraction, but everything else that was known about light at that time. In this chapter we will investigate the wave aspects of light, which are needed to explain two important phenomena—diffraction and interference. As Huygens' Principle origin; 31.1 pie is I constr In the late 1600s a Dutch mathematician-scientist, Christian Huygens, dimen proposed a very interesting idea about waves. Huygens stated that light waves spreading out from a point source may be regarded as die overlapping of tiny secondary wavelets, and that every point on ' any wave front may be regarded as a new point source of secondary waves. We see this in Figure 31.1. In other words, wave fronts are A made up of tinier wave fronts. This idea is called Huygens' principle. Look at the spherical wave front in Figure 31.2. Each point along the wave front AN is the source of a new wavelet that spreads out in a sphere from that point. -

On the Lattice Structure of Quantum Logic

BULL. AUSTRAL. MATH. SOC. MOS 8106, *8IOI, 0242 VOL. I (1969), 333-340 On the lattice structure of quantum logic P. D. Finch A weak logical structure is defined as a set of boolean propositional logics in which one can define common operations of negation and implication. The set union of the boolean components of a weak logical structure is a logic of propositions which is an orthocomplemented poset, where orthocomplementation is interpreted as negation and the partial order as implication. It is shown that if one can define on this logic an operation of logical conjunction which has certain plausible properties, then the logic has the structure of an orthomodular lattice. Conversely, if the logic is an orthomodular lattice then the conjunction operation may be defined on it. 1. Introduction The axiomatic development of non-relativistic quantum mechanics leads to a quantum logic which has the structure of an orthomodular poset. Such a structure can be derived from physical considerations in a number of ways, for example, as in Gunson [7], Mackey [77], Piron [72], Varadarajan [73] and Zierler [74]. Mackey [77] has given heuristic arguments indicating that this quantum logic is, in fact, not just a poset but a lattice and that, in particular, it is isomorphic to the lattice of closed subspaces of a separable infinite dimensional Hilbert space. If one assumes that the quantum logic does have the structure of a lattice, and not just that of a poset, it is not difficult to ascertain what sort of further assumptions lead to a "coordinatisation" of the logic as the lattice of closed subspaces of Hilbert space, details will be found in Jauch [8], Piron [72], Varadarajan [73] and Zierler [74], Received 13 May 1969. -

Relational Quantum Mechanics

Relational Quantum Mechanics Matteo Smerlak† September 17, 2006 †Ecole normale sup´erieure de Lyon, F-69364 Lyon, EU E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this internship report, we present Carlo Rovelli’s relational interpretation of quantum mechanics, focusing on its historical and conceptual roots. A critical analysis of the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen argument is then put forward, which suggests that the phenomenon of ‘quantum non-locality’ is an artifact of the orthodox interpretation, and not a physical effect. A speculative discussion of the potential import of the relational view for quantum-logic is finally proposed. Figure 0.1: Composition X, W. Kandinski (1939) 1 Acknowledgements Beyond its strictly scientific value, this Master 1 internship has been rich of encounters. Let me express hereupon my gratitude to the great people I have met. First, and foremost, I want to thank Carlo Rovelli1 for his warm welcome in Marseille, and for the unexpected trust he showed me during these six months. Thanks to his rare openness, I have had the opportunity to humbly but truly take part in active research and, what is more, to glimpse the vivid landscape of scientific creativity. One more thing: I have an immense respect for Carlo’s plainness, unaltered in spite of his renown achievements in physics. I am very grateful to Antony Valentini2, who invited me, together with Frank Hellmann, to the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, in Canada. We spent there an incredible week, meeting world-class physicists such as Lee Smolin, Jeffrey Bub or John Baez, and enthusiastic postdocs such as Etera Livine or Simone Speziale. -

Prelab 5 – Wave Interference

Musical Acoustics Lab, C. Bertulani PreLab 5 – Wave Interference Consider two waves that are in phase, sharing the same frequency and with amplitudes A1 and A2. Their troughs and peaks line up and the resultant wave will have amplitude A = A1 + A2. This is known as constructive interference (figure on the left). If the two waves are π radians, or 180°, out of phase, then one wave's crests will coincide with another waves' troughs and so will tend to cancel itself out. The resultant amplitude is A = |A1 − A2|. If A1 = A2, the resultant amplitude will be zero. This is known as destructive interference (figure on the right). When two sinusoidal waves superimpose, the resulting waveform depends on the frequency (or wavelength) amplitude and relative phase of the two waves. If the two waves have the same amplitude A and wavelength the resultant waveform will have an amplitude between 0 and 2A depending on whether the two waves are in phase or out of phase. The principle of superposition of waves states that the resultant displacement at a point is equal to the vector sum of the displacements of different waves at that point. If a crest of a wave meets a crest of another wave at the same point then the crests interfere constructively and the resultant crest wave amplitude is increased; similarly two troughs make a trough of increased amplitude. If a crest of a wave meets a trough of another wave then they interfere destructively, and the overall amplitude is decreased. This form of interference can occur whenever a wave can propagate from a source to a destination by two or more paths of different lengths. -

Quantum Theory Cannot Consistently Describe the Use of Itself

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05739-8 OPEN Quantum theory cannot consistently describe the use of itself Daniela Frauchiger1 & Renato Renner1 Quantum theory provides an extremely accurate description of fundamental processes in physics. It thus seems likely that the theory is applicable beyond the, mostly microscopic, domain in which it has been tested experimentally. Here, we propose a Gedankenexperiment 1234567890():,; to investigate the question whether quantum theory can, in principle, have universal validity. The idea is that, if the answer was yes, it must be possible to employ quantum theory to model complex systems that include agents who are themselves using quantum theory. Analysing the experiment under this presumption, we find that one agent, upon observing a particular measurement outcome, must conclude that another agent has predicted the opposite outcome with certainty. The agents’ conclusions, although all derived within quantum theory, are thus inconsistent. This indicates that quantum theory cannot be extrapolated to complex systems, at least not in a straightforward manner. 1 Institute for Theoretical Physics, ETH Zurich, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to R.R. (email: [email protected]) NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2018) 9:3711 | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05739-8 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05739-8 “ 1”〉 “ 1”〉 irect experimental tests of quantum theory are mostly Here, | z ¼À2 D and | z ¼þ2 D denote states of D depending restricted to microscopic domains. Nevertheless, quantum on the measurement outcome z shown by the devices within the D “ψ ”〉 “ψ ”〉 theory is commonly regarded as being (almost) uni- lab. -

The Concept of Quantum State : New Views on Old Phenomena Michel Paty

The concept of quantum state : new views on old phenomena Michel Paty To cite this version: Michel Paty. The concept of quantum state : new views on old phenomena. Ashtekar, Abhay, Cohen, Robert S., Howard, Don, Renn, Jürgen, Sarkar, Sahotra & Shimony, Abner. Revisiting the Founda- tions of Relativistic Physics : Festschrift in Honor of John Stachel, Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, p. 451-478, 2003. halshs-00189410 HAL Id: halshs-00189410 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00189410 Submitted on 20 Nov 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. « The concept of quantum state: new views on old phenomena », in Ashtekar, Abhay, Cohen, Robert S., Howard, Don, Renn, Jürgen, Sarkar, Sahotra & Shimony, Abner (eds.), Revisiting the Foundations of Relativistic Physics : Festschrift in Honor of John Stachel, Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 451-478. , 2003 The concept of quantum state : new views on old phenomena par Michel PATY* ABSTRACT. Recent developments in the area of the knowledge of quantum systems have led to consider as physical facts statements that appeared formerly to be more related to interpretation, with free options. -

Light and Matter Diffraction from the Unified Viewpoint of Feynman's

European J of Physics Education Volume 8 Issue 2 1309-7202 Arlego & Fanaro Light and Matter Diffraction from the Unified Viewpoint of Feynman’s Sum of All Paths Marcelo Arlego* Maria de los Angeles Fanaro** Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires CONICET, Argentine *[email protected] **[email protected] (Received: 05.04.2018, Accepted: 22.05.2017) Abstract In this work, we present a pedagogical strategy to describe the diffraction phenomenon based on a didactic adaptation of the Feynman’s path integrals method, which uses only high school mathematics. The advantage of our approach is that it allows to describe the diffraction in a fully quantum context, where superposition and probabilistic aspects emerge naturally. Our method is based on a time-independent formulation, which allows modelling the phenomenon in geometric terms and trajectories in real space, which is an advantage from the didactic point of view. A distinctive aspect of our work is the description of the series of transformations and didactic transpositions of the fundamental equations that give rise to a common quantum framework for light and matter. This is something that is usually masked by the common use, and that to our knowledge has not been emphasized enough in a unified way. Finally, the role of the superposition of non-classical paths and their didactic potential are briefly mentioned. Keywords: quantum mechanics, light and matter diffraction, Feynman’s Sum of all Paths, high education INTRODUCTION This work promotes the teaching of quantum mechanics at the basic level of secondary school, where the students have not the necessary mathematics to deal with canonical models that uses Schrodinger equation. -

Lecture 9, P 1 Lecture 9: Introduction to QM: Review and Examples

Lecture 9, p 1 Lecture 9: Introduction to QM: Review and Examples S1 S2 Lecture 9, p 2 Photoelectric Effect Binding KE=⋅ eV = hf −Φ energy max stop Φ The work function: 3.5 Φ is the minimum energy needed to strip 3 an electron from the metal. 2.5 2 (v) Φ is defined as positive . 1.5 stop 1 Not all electrons will leave with the maximum V f0 kinetic energy (due to losses). 0.5 0 0 5 10 15 Conclusions: f (x10 14 Hz) • Light arrives in “packets” of energy (photons ). • Ephoton = hf • Increasing the intensity increases # photons, not the photon energy. Each photon ejects (at most) one electron from the metal. Recall: For EM waves, frequency and wavelength are related by f = c/ λ. Therefore: Ephoton = hc/ λ = 1240 eV-nm/ λ Lecture 9, p 3 Photoelectric Effect Example 1. When light of wavelength λ = 400 nm shines on lithium, the stopping voltage of the electrons is Vstop = 0.21 V . What is the work function of lithium? Lecture 9, p 4 Photoelectric Effect: Solution 1. When light of wavelength λ = 400 nm shines on lithium, the stopping voltage of the electrons is Vstop = 0.21 V . What is the work function of lithium? Φ = hf - eV stop Instead of hf, use hc/ λ: 1240/400 = 3.1 eV = 3.1eV - 0.21eV For Vstop = 0.21 V, eV stop = 0.21 eV = 2.89 eV Lecture 9, p 5 Act 1 3 1. If the workfunction of the material increased, (v) 2 how would the graph change? stop a. -

Why Feynman Path Integration?

Journal of Uncertain Systems Vol.5, No.x, pp.xx-xx, 2011 Online at: www.jus.org.uk Why Feynman Path Integration? Jaime Nava1;∗, Juan Ferret2, Vladik Kreinovich1, Gloria Berumen1, Sandra Griffin1, and Edgar Padilla1 1Department of Computer Science, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX 79968, USA 2Department of Philosophy, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX 79968, USA Received 19 December 2009; Revised 23 February 2010 Abstract To describe physics properly, we need to take into account quantum effects. Thus, for every non- quantum physical theory, we must come up with an appropriate quantum theory. A traditional approach is to replace all the scalars in the classical description of this theory by the corresponding operators. The problem with the above approach is that due to non-commutativity of the quantum operators, two math- ematically equivalent formulations of the classical theory can lead to different (non-equivalent) quantum theories. An alternative quantization approach that directly transforms the non-quantum action functional into the appropriate quantum theory, was indeed proposed by the Nobelist Richard Feynman, under the name of path integration. Feynman path integration is not just a foundational idea, it is actually an efficient computing tool (Feynman diagrams). From the pragmatic viewpoint, Feynman path integral is a great success. However, from the founda- tional viewpoint, we still face an important question: why the Feynman's path integration formula? In this paper, we provide a natural explanation for Feynman's path integration formula. ⃝c 2010 World Academic Press, UK. All rights reserved. Keywords: Feynman path integration, independence, foundations of quantum physics 1 Why Feynman Path Integration: Formulation of the Problem Need for quantization. -

High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+

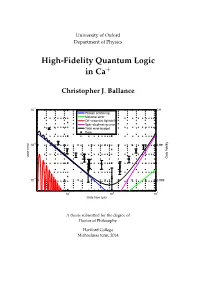

University of Oxford Department of Physics High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+ Christopher J. Ballance −1 10 0.9 Photon scattering Motional error Off−resonant lightshift Spin−dephasing error Total error budget Data −2 10 0.99 Gate error Gate fidelity −3 10 0.999 1 2 3 10 10 10 Gate time (µs) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Hertford College Michaelmas term, 2014 Abstract High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+ Christopher J. Ballance A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Michaelmas term 2014 Hertford College, Oxford Trapped atomic ions are one of the most promising systems for building a quantum computer – all of the fundamental operations needed to build a quan- tum computer have been demonstrated in such systems. The challenge now is to understand and reduce the operation errors to below the ‘fault-tolerant thresh- old’ (the level below which quantum error correction works), and to scale up the current few-qubit experiments to many qubits. This thesis describes experimen- tal work concentrated primarily on the first of these challenges. We demonstrate high-fidelity single-qubit and two-qubit (entangling) gates with errors at or be- low the fault-tolerant threshold. We also implement an entangling gate between two different species of ions, a tool which may be useful for certain scalable architectures. We study the speed/fidelity trade-off for a two-qubit phase gate implemented in 43Ca+ hyperfine trapped-ion qubits. We develop an error model which de- scribes the fundamental and technical imperfections / limitations that contribute to the measured gate error. -

Origin of Probability in Quantum Mechanics and the Physical Interpretation of the Wave Function

Origin of Probability in Quantum Mechanics and the Physical Interpretation of the Wave Function Shuming Wen ( [email protected] ) Faculty of Land and Resources Engineering, Kunming University of Science and Technology. Research Article Keywords: probability origin, wave-function collapse, uncertainty principle, quantum tunnelling, double-slit and single-slit experiments Posted Date: November 16th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-95171/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Origin of Probability in Quantum Mechanics and the Physical Interpretation of the Wave Function Shuming Wen Faculty of Land and Resources Engineering, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming 650093 Abstract The theoretical calculation of quantum mechanics has been accurately verified by experiments, but Copenhagen interpretation with probability is still controversial. To find the source of the probability, we revised the definition of the energy quantum and reconstructed the wave function of the physical particle. Here, we found that the energy quantum ê is 6.62606896 ×10-34J instead of hν as proposed by Planck. Additionally, the value of the quality quantum ô is 7.372496 × 10-51 kg. This discontinuity of energy leads to a periodic non-uniform spatial distribution of the particles that transmit energy. A quantum objective system (QOS) consists of many physical particles whose wave function is the superposition of the wave functions of all physical particles. The probability of quantum mechanics originates from the distribution rate of the particles in the QOS per unit volume at time t and near position r. Based on the revision of the energy quantum assumption and the origin of the probability, we proposed new certainty and uncertainty relationships, explained the physical mechanism of wave-function collapse and the quantum tunnelling effect, derived the quantum theoretical expression of double-slit and single-slit experiments. -

Testing the Limits of Quantum Mechanics the Physics Underlying

Testing the limits of quantum mechanics The physics underlying non-relativistic quantum mechanics can be summed up in two postulates. Postulate 1 is very precise, and says that the wave function of a quantum system evolves according to the Schrodinger equation, which is a linear and deterministic equation. Postulate 2 has an entirely different flavor, and can be roughly stated as follows: when the quantum system interacts with a classical measuring apparatus, its wave function collapses, from being in a superposition of the eigenstates of the measured observable, to being in just one of the eigenstates. The outcome of the measurement is random and cannot be predicted; the quantum system collapses to one or the other eigenstates, with a probability that is proportional to the squared modulus of the wave function for that eigenstate. This is the Born probability rule. Since quantum theory is extremely successful, and not contradicted by any experiment to date, one can simply accept the 2nd postulate as such, and let things be. On the other hand, ever since the birth of quantum theory, some physicists have been bothered by this postulate. The following troubling questions arise. How exactly is a classical measuring apparatus defined? How large must a quantum system be, before it can be called classical? The Schrodinger equation, which in principle is supposed to apply to all physical systems, whether large or small, does not answer this question. In particular, the equation does not explain why the measuring apparatus, say a pointer, is never seen in a quantum superposition of the two states `pointer to the left’ and `pointer to the right’? And if the equation does apply to the (quantum system + apparatus) as a whole, why are the outcomes random? Why does collapse, which apparently violates linear superposition, take place? Where have the probabilities come from, in a deterministic equation (with precise initial conditions), and why do they obey the Born rule? This set of questions generally goes under the name `the quantum measurement problem’.