If You Have Issues Viewing Or Accessing This File Contact Us at NCJRS.Gov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC 1 Dear Candidate, in Preparation for the Graphic Design & Illu

Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC Dear Candidate, In preparation for the Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC certification exam, we’ve put together a set of practice materials and example exam items for you to review. What you’ll find in this packet are: • Topic areas and objectives for the exam. • Links to practice tutorials and files. • Practice exam items. We’ve assembled excerpted material from the Adobe Illustrator CC Learn and Support page, and the Visual Design curriculum to highlight a few of the more challenging techniques covered on the exam. You can work through these technical guides and with the provided image files (provided separately). Additionally, we’ve included the certification objectives so that you are aware of the elements that are covered on the exam. Finally, we’ve included practice exam items to give you a feel for some of the items. These materials are meant to help you familiarize yourself with the areas of the exam so are not comprehensive across all the objectives. Thank you, Adobe Education Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Photoshop and Creative Cloud are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems 1 Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. © 2017 Adobe Systems Incorporated. All rights reserved. Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC Adobe Certified Associate in Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC (2015) Exam Structure The following lists the topic areas for the exam: • Setting project requirements • Understanding Digital Graphics and Illustrations • Understanding Adobe Illustrator • Creating Digital Graphics and Illustrations Using Adobe Illustrator • Archive, Export, and Publish Graphics Using Adobe Illustrator Number of Questions and Time • 40 questions • 50 minutes Exam Objectives Domain 1.0 Setting Project Requirements 1.1 Identify the purpose, audience, and audience needs for preparing graphics and illustrations. -

617.727.5944 2.7 Labeling a Picture Or a Diagram

BPS Curriculum Framework > Informational/Explanatory Text > Grade 2 > Drafting and Revising > Labeling a picture or diagram 2.7 Labeling a picture or a Connection : We have been noticing the beautiful pictures and helpful diagram diagrams in our mentor text for “all-about” books. We have even added pictures and diagrams to our own writing to really give our readers a better idea of what our subject looks like, but there is still one more thing we need to think about. We need to be sure our readers understand what they are looking at. Learning Objective: Students will label pictures and Teaching : Labeling our pictures gives our readers a better diagrams from the outdoor understanding of what they are looking at. Our labels help the reader classroom know exactly what they are seeing. It may tell the time of the year, the location, the size, or the specific parts of the subject they are looking at. Let’s look at The “Saddle Up!” Section in the “Kids book of Horses” and see how the author has used labels to teach us the parts of a Mentor Texts: “Volcanoes”; saddle. “Bears, Bears, Bears”; “Try It Think about something in the classroom and tell your partner “Apples”; “The Pumpkin what you might have to label if you were going to illustrate this object. Book”; “ The Kids Horse Book ”, Share out with class. Sylvia Funston Instructions to students for Independent Outdoor Writing : 1. Today, when we go out to the outdoor classroom we are going to choose an object to illustrate. It can be from our classroom list or anything else you see outside (at boat in the harbor, a truck or car going by, a small animal scampering away, or items on the playground: a slide or climbing frame. -

Information Visualization Lecture 5

Information Visualization Lecture 5 IVIS15 Skylike (link to project, link to video) Mario Romero 2016/02/02 Proposal for Skylike IVIS15 Skylike proposal on Feb 13, 2015: “make night sky constellations from your network of friends.” 2016-02-02 IVIS16 L5 2 Feedback to Proposal: link to presentation PDF Diana, Andrés, Willie, Tomáš, Johanna: Your proposal is ambitious in some aspects and unclear in others. It is ambitious in its plan to compute constellations from network graphs. What is a constellation mathematically? You will need graph theory, a sophisticated data transformation. How many stars and links for a typical constellation? Why? Are there families of constellations? How do you represent the constellations within the network? What are the view transformations? How do you provide overview, zooming, filtering, details on demand? You need to focus. Who is your user? What are the tasks? Where do you get your raw data? You need refine your ideas. Using the 4K screen with the kinect may work. 2016-02-02 IVIS16 L5 3 Skylikes feedback to ”Hello World” Demo Diana, Andrés, Willie, Tomáš, Johanna: Your choice of focusing on Goodreads is wise. Your Hello World demo worked very well and it gave your classmates a concrete opportunity to provide actionable feedback. Good work. Your challenge remains the graph theory to compute reasonable constellations in the number of stars and edges and their location. For example, should you strive for planar graphs? How many nodes and edges? Where do you place the cut off? Also, you have to think about your query system and the permanence of the constellations across users, sessions, and networks of friends. -

Guns, More Crime Author(S): Mark Duggan Source: Journal of Political Economy, Vol

More Guns, More Crime Author(s): Mark Duggan Source: Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 109, No. 5 (October 2001), pp. 1086-1114 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/322833 Accessed: 03-04-2018 19:37 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Political Economy This content downloaded from 153.90.149.52 on Tue, 03 Apr 2018 19:37:56 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms More Guns, More Crime Mark Duggan University of Chicago and National Bureau of Economic Research This paper examines the relationship between gun ownership and crime. Previous research has suffered from a lack of reliable data on gun ownership. I exploit a unique data set to reliably estimate annual rates of gun ownership at both the state and the county levels during the past two decades. My findings demonstrate that changes in gun ownership are significantly positively related to changes in the hom- icide rate, with this relationship driven almost entirely by an impact of gun ownership on murders in which a gun is used. -

Graphics Formats and Tools

Graphics formats and tools Images à recevoir Stand DRG The different types of graphics format Graphics formats can be classified broadly in 3 different groups -Vector - Raster (or bitmap) - Page description language (PDL) Graphics formats and tools 2 Vector formats In a vector format (revisable) a line is defined by 2 points, the text can be edited Graphics formats and tools 3 Raster (bitmap) format A raster (bitmap) format is like a photograph; the number of dots/cm defines the quality of the drawing Graphics formats and tools 4 Page description language (PDL) formats A page description language is a programming language that describes the appearance of a printed page at a higher level than an actual output bitmap Adobe’s PostScript (.ps), Encapsulated PostScript (.eps) and Portable Document Format (.pdf) are some of the best known page description languages Encapsulated PostScript (.eps) is commonly used for graphics It can contain both unstructured vector information as well as raster (bitmap) data Since it comprises a mixture of data, its quality and usability are variable Graphics formats and tools 5 Background Since the invention of computing, or more precisely since the creation of computer-assisted drawing (CAD), two main professions have evolved - Desktop publishing (DTP) developed principally on Macintosh - Computer-assisted drawing or design (CAD) developed principally on IBM (International Business Machines) Graphics formats and tools 6 Use of DTP applications Used greatly in the fields of marketing, journalism and industrial design, DTP applications fulfil the needs of various professions - from sketches and mock-ups to fashion design - interior design - coachwork (body work) design - web page design -etc. -

Current Strategies for Reducing Recidivism

CURRENT STRATEGIES FOR REDUCING RECIDIVISM LISE MCKEAN, PH.D. CHARLES RANSFORD CENTER FOR IMPACT RESEARCH AUGUST 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PROJECT FUNDER Chicago Community Organizing Capacity Building Initiative PROJECT PARTNERS Developing Justice Coalition Coalition Members ACORN Ambassadors for Christ Church Brighton Park Neighborhood Council Chicago Coalition for the Homeless Community Renewal Society Developing Communities Project Foster Park Neighborhood Council Garfield Area Partnership Global Outreach Ministries Inner-City Muslim Action Network Northwest Neighborhood Federation Organization of the North East Protestants for the Common Good SERV-US Southwest Organizing Project Target Area Development Corp. West Side Health Authority Center for Impact Research Project Staff Lise McKean, Ph.D., Project Director Charles Ransford 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………… 4 INTRODUCTION …………………………...……………………….. 8 STUDY DESIGN……………………………………………………… 9 DEFINING RECIDIVISM……………………………………………… 11 FINDINGS ON PROGRAMS ………………………………………….. 15 Treatment Programs………………………………………….. 15 Educational Programs……………………………………....... 18 Employment Programs………………………………………. 19 Other Types of Programs……………………………….......... 21 RECOMMENDATIONS …………..…………………………………… 24 APPENDIX…..………………………………………………………. 27 3 CURRENT STRATEGIES FOR REDUCING RECIDIVISM Lise McKean, Ph.D., and Charles Ransford Center for Impact Research August 2004 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Recidivism is the relapse into criminal activity and is generally measured by a former prisoner’s return to prison for a new offense. Rates of recidivism reflect the degree to which released inmates have been rehabilitated and the role correctional programs play in reintegrating prisoners into society. The rate of recidivism in the U.S. is estimated to be about two-thirds, which means that two-thirds of released inmates will be re-incarcerated within three years. High rates of recidivism result in tremendous costs both in terms of public safety and in tax dollars spent to arrest, prosecute, and incarcerate re-offenders. -

The Language of Spatial ANALYSIS CONTENTS

The Language of spatial ANALYSIS CONTENTS Foreword How to use this book Chapter 1 An introduction to spatial analysis Chapter 2 The vocabulary of spatial analysis Understanding where Measuring size, shape, and distribution Determining how places are related Finding the best locations and paths Detecting and quantifying patterns Making predictions Chapter 3 The seven steps to successful spatial analysis Chapter 4 The benefits of spatial analysis Case study Bringing it all together to solve the problem Reference A quick guide to spatial analysis Additional resources FOREWORD Watching the GIS industry grow for more than 25 years, I have seen innovation in the problems we solve, the people we can reach through technology, the stories we tell, and the decisions that help make our organizations and the world more successful. However, what has not changed is our longstanding goal to better understand our world through spatial analysis. Traveling the world I have met people from many diverse cultures who work in a wide range of industries. However, as I listen to their mission and challenges, there is a common pattern: we all speak the same language—it is the language of spatial analysis. This language consists of a core set of questions that we ask, a taxonomy that organizes and expands our understanding, and the fundamental steps to spatial analysis that embody how we solve spatial problems. I encourage each of you to learn and communicate to the world the power of spatial analysis. Learn the definition, learn the vocabulary and the process, and most important, be able to speak this language to the world. -

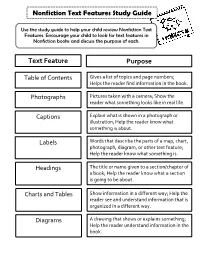

Nonfiction Text Features Study Guide Text Feature Purpose

Nonfiction Text Features Study Guide Use the study guide to help your child review Nonfiction Text Features. Encourage your child to look for text features in Nonfiction books and discuss the purpose of each. Text Feature Purpose Gives a list of topics and page numbers; Table of Contents Helps the reader find information in the book. Photographs Pictures taken with a camera; Show the reader what something looks like in real life. Captions Explain what is shown in a photograph or illustration; Help the reader know what something is about. Labels Words that describe the parts of a map, chart, photograph, diagram, or other text feature; Help the reader know what something is. Headings The title or name given to a section/chapter of a book; Help the reader know what a section is going to be about. Charts and Tables Show information in a different way; Help the reader see and understand information that is organized in a different way. Diagrams A drawing that shows or explains something; Help the reader understand information in the book. Text Feature Purpose Textboxes A box or some other shape that contains text; Show the reader that information is important or interesting. A picture of what something looks like on the Cutaways inside or from another point of view; Help the reader see all parts of something. Types of Print Print can be bold, different colors, fonts, and sizes; Show the reader that something is important or interesting. Close Ups Photographs that have been zoomed in or enlarged to help the reader see something better. -

A Curriculum Guide

FOCUS ON PHOTOGRAPHY: A CURRICULUM GUIDE This page is an excerpt from Focus on Photography: A Curriculum Guide Written by Cynthia Way for the International Center of Photography © 2006 International Center of Photography All rights reserved. Published by the International Center of Photography, New York. Printed in the United States of America. Please credit the International Center of Photography on all reproductions. This project has been made possible with generous support from Andrew and Marina Lewin, the GE Fund, and public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs Cultural Challenge Program. FOCUS ON PHOTOGRAPHY: A CURRICULUM GUIDE PART IV Resources FOCUS ON PHOTOGRAPHY: A CURRICULUM GUIDE This section is an excerpt from Focus on Photography: A Curriculum Guide Written by Cynthia Way for the International Center of Photography © 2006 International Center of Photography All rights reserved. Published by the International Center of Photography, New York. Printed in the United States of America. Please credit the International Center of Photography on all reproductions. This project has been made possible with generous support from Andrew and Marina Lewin, the GE Fund, and public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs Cultural Challenge Program. FOCUS ON PHOTOGRAPHY: A CURRICULUM GUIDE Focus Lesson Plans Fand Actvities INDEX TO FOCUS LINKS Focus Links Lesson Plans Focus Link 1 LESSON 1: Introductory Polaroid Exercises Focus Link 2 LESSON 2: Camera as a Tool Focus Link 3 LESSON 3: Photographic Field -

Illustration Degree Offered: Bachelor of Fine Arts

Illustration Degree Offered: Bachelor of Fine Arts Minors Offered: • Art • Art History • Graphic Design • Illustration • Painting • Sculpture • Theatre Arts The BFA in Illustration focuses on developing drawing skills and their application in a professional en vironment, including editorial illustration, children's book illustration, web-site development, and character design for animation. Illustration at Daemen: • Demonstrate a high level of accomplishment with materials related to the graphic arts. • Visually present a narrative voice through individual compositions or series. • Work within a variety of media to explore editorial or sequential imagery. • Develop an editorial voice to support campaigns, storylines, or public initiatives. Illustration Emphasis: The BFA in Illustration at Daemen College combines the creative process of a fine artist with the problem solving techniques and communication skills of a commercial designer. Students are taught to brainstorm solutions, generate new ideas, and explore the materials and techniques best suited to present an idea. By graduation, the Illustration student will have ex perience in editorial, sequential, computer, packaging and storyboard illustration. Illustration studio courses are supported by substantive drawing instruction, as well as fundamental graphic design con cepts. The program's focus on exploration and process prepares students to develop a portfolio to successfully acquire freelance illustration work, or a full-time position in the publishing or digital communications industry. Faculty: The Illustration faculty work in a variety of professional situations by providing illustrations to magazines, poster cam paigns, and websites. Each maintains a freelance career while simultaneously working with students at Daemen in the development of projects and exhibits. 4103 Suggested Course Sequence for Illustration: 4897 10/16 For more information, contact Christian Brandjes in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts at [email protected] or 716-839-8463. -

Classroom Activity Pictorial Language: Mesoamerican Reading

Classroom Activity Pictorial Language: Mesoamerican Reading and Writing ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Enduring Understanding The basic unit of pictorial language is the pictogram, a graphic symbol that represents an idea or concept. Pictorial language, although an ancient tradition, is still employed in colloquialisms today. Grades K–12 Time One class period Visual Art Concepts Symbol, meaning, representation, communication, Materials Paper and pencils. Optional: colored pencils Talking about Art Pictorial language, or an ideographic writing system is a method of communication based on the ideogram/pictogram. An ideogram is a symbol that represents an idea or concept, while a pictogram conveys meaning through realistic resemblance. These symbols, unique to every ancient civilization, formed a hieroglyphic dictionary for Mesoamerican scribes. Much of the history of Mesoamerica can be traced through their pictorial language, independently developed around 950 and widely adopted throughout southern Mexico by 1300. It was used to record and preserve the history, genealogy, and mythology of Mixtec, Nahua, and Zapotec cultures and appears most prominently in painted books called codices. (For more information about codices and for tips on how to create one, see the accompanying lesson plan Create Your Lord Eight Deer Own Codex.) View and discuss the Codex Nuttal, Mexico, Western Oaxaca, 15th–16th century. What is going on here? Who are the characters? What is the setting? What action is taking place? How did the scribe or artist use line, shape, space, color, and composition to tell the story? This codex tells the story of Lord Eight Deer, an epic Mixtec conqueror and cult hero who lived between 1063 and 1115. -

Ellie Rastian Product Designer 017675131412

[email protected] Ellie Rastian www.65ping.studio Product Designer 017675131412 Experience Certification dunnhumby Germany GmbH Nielsen Norman Group 2018 March - 2020 July (2019) Berlin, Germany UX Certified Web designer Starting as a visual designer, I worked on e- Scrum.org commerce projects related to European Market. (2020) Soon, I showed my skills as a UX/UI designer and Professional Scrum Master was assigned to design the internal website for the Creative Services Team. I worked with the UX team and CS team to develop the website. University of Minnesota coursera Saatchi & Saatchi (2018 - 2019) 2015 March - 2016 June User Interface Design Specialization Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Visual Designer Involved in ideation and execution for ATL & BTL Education advertising campaigns, proposals and pitches. Clients: MINI Malaysia, Bank Simpanan Nasional Malaysian Institute of Art (BSN). (2014 - 2016) Graphic Design Freelancer 2014 July - Present Shiraz University Visual Designer, UX Designer, Illustrator (2008 - 2010) I have spent over seven years crafting and delivering Bachelor of Business Administration unique digital experiences for global companies and BBA, Accounting and Finance startups such as MINI, Sam Media, Elixir Berlin Khalij Fars Online Language 2008 April - 2010 September Booshehr, Iran English Full professional proficiency Limited working proficiency, B1 Financial Accountant German Persian Full professional proficiency Malay Elementary proficiency Skills Design Tools Interaction Design, Visual Design, Information Sketch, InVision,