Dangerous Approaches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5Th – 14Th MARCH 2020

5th – 14th MARCH 2020 Photo: Jan-Arne Pettersen Jan-Arne Photo: Finally the time has come for Narvik and races in Narvik are the most important races in Narvikfjellet to be filled with alpinists, their careers so far. We know that some of the managers, drivers, service personnel, parents, competitors will become world stars in a few and others from all over the world. years time. The last big international races in Narvik were However, everyone is equally important to us, in 1992 and 1996, when we held the World and our goal is for everyone to remember this Cup women’s race. We have great ambitions championship in Narvik as a great experience. for future events, and the goal is to be able to apply for the World Championships in We hope that everyone has a wonderful alpine skiing in 2027. In order to achieve this and memorable stay in Narvik, and that the dream, we have to deliver at all levels for all conditions are the runs on the mountain - from children’s the same for all races to now, the FIS Alpine Junior World Ski competitors. Championships 2020. We have worked long and hard to provide the best runs, the best food, the best ceremonies, With sporting and the best logistics for each and every one greetings of you during the championships. Many of the competitors here are attempting to become Erik D. Plener World Cup skiers, and, for most of them, these CEO, Narvik Alpin AS On behalf of Narvik and Northern Norway beautiful fjords and lakes has immense value I welcome you all to the FIS Alpine Junior for us. -

AIBN Accident Boeing 787-9 Dreamliner, Oslo Airport, 18

Issued June 2020 REPORT SL 2020/14 REPORT ON THE AIR ACCIDENT AT OSLO AIRPORT GARDERMOEN, NORWAY ON 18 DECEMBER 2018 WITH BOEING 787-9 DREAMLINER, ET-AUP OPERATED BY ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES The Accident Investigation Board has compiled this report for the sole purpose of improving flight safety. The object of any investigation is to identify faults or discrepancies which may endanger flight safety, whether or not these are causal factors in the accident, and to make safety recommendations. It is not the Board's task to apportion blame or liability. Use of this report for any other purpose than for flight safety shall be avoided. Accident Investigation Board Norway • P.O. Box 213, N-2001 Lillestrøm, Norway • Phone: + 47 63 89 63 00 • Fax: + 47 63 89 63 01 www.aibn.no • [email protected] This report has been translated into English and published by the AIBN to facilitate access by international readers. As accurate as the translation might be, the original Norwegian text takes precedence as the report of reference. Photos: AIBN and Trond Isaksen/OSL The Accident Investigation Board Norway Page 2 INDEX ACCIDENT NOTIFICATION ............................................................................................................ 3 SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1. FACTUAL INFORMATION .............................................................................................. 4 1.1 History of the flight ............................................................................................................. -

Environmental Policies at Europe's Airports

Foreword The study author, Jeffrey Gazzard, is currently Jeffrey Gazzard has represented environmental President of the Union Européene Contre les NGO’s on air transport and environment issues Nuisances des Avions, an umbrella group at UN IPCC meetings, UN FCCC COP assemblies representing grassroots citizen’s organisations and UN WHO policy development consultations, around Europe’s major airports. He is also a as well as numerous similar national and European steering group member of Friends of the Earth fora. He is a frequent speaker and panellist at Europe’s “The Right Price for Air Travel” commercial, government and NGO conferences campaign, a board member of the UK’s Aviation and events. Environment Federation and is an active campaigner seeking to control and reduce the negative environmental effects of air transport at local, national and international levels. Author’s note I would like to thank my colleagues for their I would also like to thank all those who either support and encouragement during the research, generously wrote commentaries or gave writing and production phases of this report. In permission for us to reproduce articles from particular Hilde Stroot at Milieudefensie, other published sources in this report. I would Amsterdam, for her efforts in managing like to personally thank all the funding questionnaire responses and analysis; Paul de organisations that supported this project. Clerck, also at Milieudefensie, for initiating and supporting the project in his role as co-ordinator Whilst I wrote the report, its publication reflects of “The Right Price for Air Travel” campaign; Tim a team effort that I am proud to have been a part Johnson, Director of the Aviation Environment of. -

400 Hz September 2020 1 of 28

LIST OF REFERENCES ‐ 400 Hz September 2020 1 of 28 End‐user Segment Product Units Location Year Algiers Airport Airport 2400 ‐ 90 kVA 23 Algeria 2017 BOU‐SAÂDA Helicopter Hangar Airport 2300 ‐ 60 kVA 4 Algeria 2014 Air Algerie Airline 2400 ‐ 90 kVA 2 Algeria 2019 Air Algerie Airline 2400 ‐ 180 kVA 2 Algeria 2019 Protection civile Defence 2400 ‐ 30 kVA w/ARU 2 Algeria 2020 Protection civile Defence 2400 ‐ 30 kVA 2 Algeria 2019 Aerolineas Airline 2400 ‐ 60 kVA 1 Argentina 2020 Aerolineas Airline 2400 ‐ 30 kVA 1 Argentina 2016 Austral Airlines Airline 2400 ‐ 90 kVA 1 Argentina 2017 Brisbane Airport Airport 7400 ‐ 90 kVA 1 Australia 2018 Brisbane Airport Airport 2300 ‐ Power Coil 8 Australia 2013 Darwin Airport Airport 7400 ‐ 90 kVA 5 Australia 2019 Melbourne Airport Airport 2400 ‐ Power Coil 4 Australia 2018 Melbourne Airport Airport 2400 ‐ 90 kVA 9 Australia 2018 Melbourne Airport Airport 2400 ‐ Power Coil 2 Australia 2017 Melbourne Airport Airport 2400 ‐ 90 kVA 11 Australia 2014 Melbourne Airport Airport 2300 ‐ Power Coil 22 Australia 2011 Melbourne Airport Airport 2300 ‐ Power Coil 10 Australia 2011 Melbourne Airport Airport 2300 ‐ Power Coil 4 Australia 2009 Perth Airport Airport 2400 ‐ Power Coil 4 Australia 2017 Perth Airport Airport 2400 ‐ Power Coil 4 Australia 2017 Perth Airport Airport 2400 ‐ Power Coil 8 Australia 2017 Perth Airport Airport 2300 ‐ 90 kVA w/TRU 14 Australia 2013 Perth Airport Airport 2300 ‐ Power Coil 21 Australia 2013 Perth Airport Airport 2300 ‐ Power Coil 2 Australia 2013 Perth Airport Airport 2300 ‐ Power Coil -

LIST of REFERENCES ITW GSE 400 Hz Gpus AIRPORTS

Page 1 of 15 January 2017 LIST OF REFERENCES ITW GSE 400 Hz GPUs AIRPORTS Alger Airport Algeria 2005 Zvartnots Airport Armenia 2007 Brisbane Airport Australia 2013 Melbourne Airport Australia 2011-14 Perth Airport Australia 2011-12-13 Klagenfurt Airport Austria 1993 Vienna International Airport Austria 1995-2001-14-15 Bahrain International Airport Bahrain 2010-12 Minsk Airport Belarus 2014 Brussels International Airport Belgium 2001-02-08-15-16 Charleroi Airport Belgium 2006 Sofia Airport Bulgaria 2005 Air Burkina Burkina Faso 2004 Punta Arenas Chile 2001 Santiago Airport Chile 2011 Pointe Noitre Airport Congo Brazzaville 2009-10 Dubrovnik Airport Croatia 2014-16 La Habana Airport Cuba 2010 Larnaca Airport Cyprus 2008 Ostrava Airport Czech Republic 2010 Prague Airport Czech Republic 1996-97-2002-04-05-07-12-14-16 Aalborg Airport Denmark 1997-98-99-2012-15 Billund Airport Denmark 1999-2000-02-08-12-13-16 Copenhagen Airports Authorities Denmark 89-93-99-2000-01-03-07-09-10-11-12-13-14-15-16 Esbjerg Airport Denmark 2007-08-14 Hans Christian Andersen Airport (Odense) Denmark 1991-95-2015 Roenne Airport Denmark 1993 Karup Airport Denmark 1997-2016 Curacao Airport Dutch Antilles 2007 Cairo Intl. Airport Egypt 2015 Tallinn Airport Estonia 2004-05-14 Aéroport de Malabo Equatorial Guinea 2012 Vága Floghavn Faroe Islands 2015 Helsinki-Vantaa Airport Finland 1996-97-2000-05-06-09-10-13-14 Rovaniemi Airport Finland 2000 Turku Airport Finland 2014 Aéroport d’Aiglemont for Prince Aga Khan France 20007 Aéroport de Biarritz France 2009 Aéroport de Brest -

Atlas of Airports

COMPOSMENT TYPOLOGY CONFIGURATION AIRFIELDS NORWAY Norwegian airports with more than 100 000 passengers This airport research combines selected airports that with a certain annual passengers in Norway. The methodology of juxtaposition, the analysis of Terminals, Runway, Airport cities patterns as well as configuration, spatial, morphology, forms, which serve as a base-data for airport design. TYPOLOGY OF AIRPORTS - NORWAY SELECTED AIRPORT ANALYSIS & STUDY con- tent Oslo 3 Bergen 5 Stavanger 7 Trondheim 9 Tromsø 11 Sandefjord 13 Bodø 15 Kristiansand 17 Ålesund 19 Haugesund 21 Narvik and Harstad (Evenes Airport) 23 Alta 25 VMolde 27 Kristiansund 29 Kirkenes 31 Bardufoss 33 Hammerfest 35 Longyearbyen, Svalbard 37 Florø 39 Stokmarknes 41 Mo i Rana 43 Runway 45 Configuration 47 Airport cities 49 Terminals 51 OSL 60°12’10’’N 011°05’02’’E Airport type Public Operator Oslo Lufthavn AS Serves Oslo, Norway Location Gardermoen, Ullensaker, Akershus Runways 3,600/2,950 Passengers 25,788,610 International 14,567,406 Domestic 11,221,204 Aircraft movements 237,618 Cargo (tonnes) 130,301 3 OSL RUNWAY TERMINAL AIRPORT CITY STRUCTURE 1 AIRPORT CITY PATTERN TRANSFER AIRPORT CITY PATTERN The first airports to serve Oslo was Kjeller Airport that opened in 1912 and Gressholmen Airport that served seaplanes after its opening in 1926. The airport location was first used by the Norwegian Army from 1940, with the first military airport facilities being built during the 1940s. An expansion with a new terminal building and a third pier is scheduled to open in 2017.Oslo Airport is the largest and busiest of three major international airports located around Oslo. -

FINAL ACTS of the EXTRAORDINARY ADMINISTRATIVE RADIO CONFERENCE GENEVA, 1951 Volume III ANNEX 2 Region 1

This electronic version (PDF) was scanned by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Library & Archives Service from an original paper document in the ITU Library & Archives collections. La présente version électronique (PDF) a été numérisée par le Service de la bibliothèque et des archives de l'Union internationale des télécommunications (UIT) à partir d'un document papier original des collections de ce service. Esta versión electrónica (PDF) ha sido escaneada por el Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT) a partir de un documento impreso original de las colecciones del Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la UIT. (ITU) ﻟﻼﺗﺼﺎﻻﺕ ﺍﻟﺪﻭﻟﻲ ﺍﻻﺗﺤﺎﺩ ﻓﻲ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﺃﺟﺮﺍﻩ ﺍﻟﻀﻮﺋﻲ ﺑﺎﻟﻤﺴﺢ ﺗﺼﻮﻳﺮ ﻧﺘﺎﺝ (PDF) ﺍﻹﻟﻜﺘﺮﻭﻧﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻨﺴﺨﺔ ﻫﺬﻩ .ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﻤﺘﻮﻓﺮﺓ ﺍﻟﻮﺛﺎﺋﻖ ﺿﻤﻦ ﺃﺻﻠﻴﺔ ﻭﺭﻗﻴﺔ ﻭﺛﻴﻘﺔ ﻣﻦ ﻧ ﻘ ﻼً 此电子版(PDF版本)由国际电信联盟(ITU)图书馆和档案室利用存于该处的纸质文件扫描提供。 Настоящий электронный вариант (PDF) был подготовлен в библиотечно-архивной службе Международного союза электросвязи путем сканирования исходного документа в бумажной форме из библиотечно-архивной службы МСЭ. BIBLIOTHÈQUE DE L’U. I. T. ACTES FINALS TOT DE LA CONFÉRENCE ADMINISTRATIVEI EXTRAORDINAIRE DES RADIOCOMMUNICATIONS GENÈVE 1951 Volume III ANNEXE 2 Région 1 FINAL ACTS OF THE EXTRAORDINARY ADMINISTRATIVE RADIO CONFERENCE GENEVA, 1951 Volume III ANNEX 2 Region 1 ACTAS FINALES UNION DE LA INTERNATIONALE CONFERENCIA ADMINISTRATIVA EXTRAORDINARIA DE RADIOCOMUNICACIONES DES TÉLÉCOMMUNICATIONS GINEBRA 1951 GENÈVE Volumen III ANEXO 2 Región -

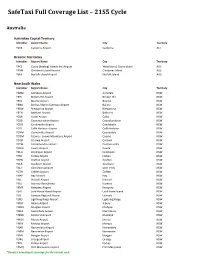

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

Vision-1 Terrain Database 1401 3015.( )-34-3631 Original 5 May 2015, Revision C 18 September 2015 Page 1 of 14 SERVICE BULLETIN

Service Bulletin Number 3015.( )-34-3631 Announcement of the Availability of Vision-1® Terrain Database 1401 NOTE: Revision C to this Service Bulletin provides Field Loading information and updated kit pricing. A. Effectivity This Service Bulletin is applicable to Vision-1 P/N 3015-XX-XX configured with SCN 10.0 and later. B. Compliance Installation of Terrain Database 1401 is optional. Consideration should also be given to the length of time since the database was last updated. Each Terrain Database incorporates all changes and updates from the previous databases. NOTICE This Terrain Database can be field loaded into Vision-1. Contact Universal Avionics to obtain database loading kit part number P12104 which includes the Field Loading Procedures, Zip disks and USB flash drives to load Terrain Database 1401. Loading terrain databases into Vision-1 requires a Solid State Data Transfer Unit (SSDTU) (P/N 1408-00-X or 1409-00-2) or DTU-100 (P/N 1406-01-X or 1407-01-1) with Mod 1 marked on the nameplate. For operators using a DTU-100 without Mod 1, the Vision-1 units should be sent to Universal Avionics for updating. The terrain database contains five disks with 450 Mb of data and takes over an hour to load. Because of this, DTU-100 units without Mod 1 may fail due to overheating causing the Vision-1 Terrain Database to become corrupted and the Vision-1 system unserviceable. If the Vision-1 unit is returned to Universal Avionics for update of the terrain database or because of failure during field loading, the repair center will update the database and perform any modifications and updates to the unit. -

Airports and Airline Companies (Carriers) Coverage (Updated 080610)

Airports and airline companies (carriers) coverage (updated 080610) Traveas ambition is to have a complete coverage on a global travel market, and to have the best local coverage as possible on each market Traveas operates. At present, Traveas offers relevant and immediate coverage on the following airports and airline companies (carriers): Airport: Airline Company (carrier): (Airport code - ”Airport name”) (Airline code - ”Airline name”) AAL,"Aalborg Airport" 3K,"Jetstar Asia" AAR,"Tirstrup Airport" 6E,"IndiGo" ABZ,"Dyce Airport" 7H,"Era Aviation" ACE,"Lanzarote Airport" 9W,"Jet Airways (India)" AES,"Vigra Airport" AA,"American Airlines" AGP,"Malaga Airport" AC,"Air Canada" AKL,"Auckland International Airport" AF,"Air France" ALC,"Alicante Airport" AI,"Air India" ALF,"Alta Airport" AM,"Aeromexico" AMS,"Amsterdam-Schiphol Airport" AR,"Aerolineas Argentinas" ANR,"Deurne Airport" AS,"Alaska Airlines" ANX,"Andenes Airport" AT,"Royal Air Maroc" ARN,"Arlanda Airport" AY,"Finnair" ATH,"Eleftherios Venizelos International Airport" AZ,"Alitalia" AYT,"Antalya Airport" B6,"JetBlue Airways" BCN,"Barcelona Airport" BA,"British Airways" BDS,"Papola Casale Airport" BD,"bmi" BDU,"Bardufoss Airport" BW,"Caribbean Airlines" BEG,"Beograd Airport" C6,"Canjet Airlines" BEY,"Beirut International Airport" CA,"Air China International" BFS,"Belfast International Airport" CI,"China Airlines" BGO,"Flesland Airport" CM,"COPA" BGY,"Orio Al Serio Airport" CO,"Continental Airlines" BHD,"Belfast City Airport" CX,"Cathay Pacific Airways" BHX,"Birmingham International -

D. NORWAY's PARTICIPATION in INTERNATIONAL PEACE

D. NORWAY’s PARTICIPATION IN INTERNATIONAL PEACE OPERATIONS Ever since the United Nations was established in 1945, Norway has considered the work of the United Nations to be of major importance. The UN Charter gives the United Nations an important role in maintaining international peace and security. It has always been a goal of Norwegian foreign policy to contribute towards strengthening the UN apparatus for peacekeeping operations, handling of crises and peaceful settlement of disputes. Participation in UN peace operations is therefore listed as one of our defence forces’ main objec- tives. The UN peace forces have helped reduce tension in many regions. The award of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1988 confirms that the UN forces have played a positive peacekeeping role. Since 1988 the UN has established more operations than dur- ing the last 40 years. The increased importance of the UN’s role in the issues related to international peace and security is manifested by this expansion. This is expected to continue. Military, medical and humanitarian assistance is also regard- ed as a means of advancing national security since UN opera- tions contribute to damping down and stabilising volatile situ- ations. The Storting decided in 1964 that Norwegian contingents can be made available to the United Nations for peace opera- tions. The Defence Establishment has earmarked a special standby force for this task, composed of voluntary personnel, which can be called upon at short notice following a direct request from the UN. The expansion that has taken place, both concerning the number of UN operations and their tasks, has induced the need to undertake a general review and updating with regard to the experience we have gained, as well as the setting for our military UN engagements. -

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze Zestawienie Zawiera 8372 Kody Lotnisk

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze zestawienie zawiera 8372 kody lotnisk. Zestawienie uszeregowano: Kod ICAO = Nazwa portu lotniczego = Lokalizacja portu lotniczego AGAF=Afutara Airport=Afutara AGAR=Ulawa Airport=Arona, Ulawa Island AGAT=Uru Harbour=Atoifi, Malaita AGBA=Barakoma Airport=Barakoma AGBT=Batuna Airport=Batuna AGEV=Geva Airport=Geva AGGA=Auki Airport=Auki AGGB=Bellona/Anua Airport=Bellona/Anua AGGC=Choiseul Bay Airport=Choiseul Bay, Taro Island AGGD=Mbambanakira Airport=Mbambanakira AGGE=Balalae Airport=Shortland Island AGGF=Fera/Maringe Airport=Fera Island, Santa Isabel Island AGGG=Honiara FIR=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGH=Honiara International Airport=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGI=Babanakira Airport=Babanakira AGGJ=Avu Avu Airport=Avu Avu AGGK=Kirakira Airport=Kirakira AGGL=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova Airport=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova, Santa Cruz Island AGGM=Munda Airport=Munda, New Georgia Island AGGN=Nusatupe Airport=Gizo Island AGGO=Mono Airport=Mono Island AGGP=Marau Sound Airport=Marau Sound AGGQ=Ontong Java Airport=Ontong Java AGGR=Rennell/Tingoa Airport=Rennell/Tingoa, Rennell Island AGGS=Seghe Airport=Seghe AGGT=Santa Anna Airport=Santa Anna AGGU=Marau Airport=Marau AGGV=Suavanao Airport=Suavanao AGGY=Yandina Airport=Yandina AGIN=Isuna Heliport=Isuna AGKG=Kaghau Airport=Kaghau AGKU=Kukudu Airport=Kukudu AGOK=Gatokae Aerodrome=Gatokae AGRC=Ringi Cove Airport=Ringi Cove AGRM=Ramata Airport=Ramata ANYN=Nauru International Airport=Yaren (ICAO code formerly ANAU) AYBK=Buka Airport=Buka AYCH=Chimbu Airport=Kundiawa AYDU=Daru Airport=Daru