Citizen Science: Knowledge, Networks and the Boundaries of Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

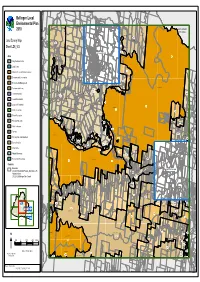

LEP 2010 LZN Template

WILD CATTLE CREEK E1E1E1 DORRIGO RU2RU2 GLENREAGH MULDIVA RU2RU2 OLD BILLINGS RD RAILWAY NATURE COAST TYRINGHAM RESERVE RD RD Bellingen Local E1EE1E11 BORRA CREEK DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK CORAMBA RD E3EE3E33 SLINGSBYS Environmental Plan LITTLE MURRAY RIVER RU2RRU2U2 RD LITTLE PLAIN CREEK BORRA CREEK TYRINGHAM COFFSCOFFS HARBOURHARBOUR 2010 RD CITYCCITYITY COUNCILCOUNCIL BREAKWELLS WILD CATTLE CREEK RD RU2RRU2U2 CORAMBA RD RU2RU2 NEAVES NEAVES RD RD SLINGSBYS RD Land Zoning Map LITTLE MURRAY RIVER OLD COAST RD E3EE3E33 RU2RRU2U2 Sheet LZN_004 E3EE3E33 DEER VALE RD OLD CORAMBA TYRINGHAM RD NTH RD ROCKY CREEK RU1RU1 BARTLETTS RD ReferRefer toto mapmap LZN_004ALZN_004A Zone RU1RRU1U1 BIELSDOWN RIVER E1EE1E11 DEER VALE RD B1 Neighbourhood Centre RU1RU1 DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK B2 Local Centre JOHNSENS WATERFALL WAY OLD CORAMBA WATERFALL WAY RD STH EE3E3E33 E1 National Parks and Nature Reserves E3E3E3 BENNETTS RD E2 Environmental Conservation WATERFALL WAY SHEPHERDS RD RU1RRU1U1 E3 Environmental Management DOME RD EVERINGHAMS ROCKY CREEK RD BIELSDOWN RIVER DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK E4 Environmental Living E3EE3E33 SP1SP1SP1 E3E3E3 SHEPHERDS RD WHISKY CEMETERYCCEMETERYEMETERY DOME RD IN1 General Industrial CREEK RD RU1RRU1U1 RU1RRU1U1 WOODLANDS RD WATERFALL R1 General Residential WAY RU1RRU1U1 PROMISED RU1RU1 E3E3E3 LAND RD WATERFALL WAY R5 Large Lot Residential WHISKY CREEK E1EE1E11 RU1RU1 DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK E1E1E1 E1EE1E11 RE1 Public Recreation BIELSDOWN RIVER E3EE3E33 ROCKY CREEK RD RE2 Private Recreation WHISKY CREEK RD RU1RRU1U1 RU2RU2 E3E3E3 -

Vicnews101 V2.Qxd

VICNEWS Number 109 August 2014 ANGFA Victoria Inc. is a regional group member of AUSTRALIA NEW GUINEA FISHES ASSOCIATION INC. Published by ANGFA Victoria Inc. PO Box 298, Chirnside Park Vic. 3116 Visit us at: www.angfavic.org and on Facebook Unravelling the Galaxias olidus species complex with Tarmo Raadik, our August meeting guest presenter Photo above: A fast flowing, pristine creek in the upper catch - ment zone of a Victorian high country river. These types of creeks are the natural habitat of upland galaxiids in the Mountain Galaxias (Galaxias olidus) species complex, with some species widespread and others confined to single, small catch - ments. This type of waterfall is often the key reason why the species survive, as their main predators, Brown Trout and Rainbow Trout, are unable to move further upstream. Many of the restricted species are also under a high risk of extinction from instream sedimentation following increasingly frequent wild fire. Photo: Tarmo Raadik Photo to right: Galaxias fuscus . Photo: Tarmo Raadik VICNEWS August 2013 PAGE 1 environments, including fish passage assessment and fish - way monitoring, environmental flow determinations, fauna assessments in degraded, pristine and remote locations, and alien species control. In particular, Tarmo has a long involvement with the compilation and management of aquatic fauna survey data, undertaking the first compilation of Victorian data in 1986, which he then continued while at the Department of Ichthyology, Museum Victoria, and later when he joined the Arthur Rylah Institute. This data compilation became the basis the new Victorian Biodiversity Atlas (VBA). Tarmo holds the roles of Taxon Manager and Data Expert Reviewer for Aquatic Fauna (fish, freshwater decapod crus - tacea and molluscs) for the VBA, and is relied upon by ARI staff and external clients for his knowledge of current tax - onomy and historical and contemporary aquatic fauna dis - tributions. -

Kalang River Health Plan

KALANG RIVER HEALTH PLAN BellingenBelligen ShireShire CouncilCouncil Bellingen Shire Healthy Rivers Program Kalang River Health Plan Title Kalang River Health Plan Date of Publication March 2010 Copyright Copyright © 2010, Bellingen Shire Council. Along with any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this report may also be reproduced in part or whole for the purposes of study, research, review and/or general information provided clear acknowledgement of the source is made. Citation Bellingen Shire Council (2010). Kalang River Health Plan. Bellingen Shire Council, NSW. ISBN 978 0 9807685 2 7 (Hard copy) ISBN 978 0 9807685 3 4 (Digital copy) Digital Copy Access This report can be accessed and downloaded on line at www.bellingen.nsw.gov.au by following the Environment prompt to the Healthy Rivers Program. Disclaimer While every care has been taken to ensure that the information contained in this report is accurate, complete and current at the time of publication, no warranty is given or implied that it is free of error or omission. No liability is accepted for any material or financial loss, damage, cost or injury arising from the use of this report. Funding Support This report has been prepared by Bellingen Shire Council with financial assistance from the NSW Government through the Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water. This document does not necessarily reflect the opinions of the NSW Government or the Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water. Cover Image Kalang River estuary Bellingen Shire Healthy Rivers Program Kalang River Health Plan KALANG RIVER HEALTH PLAN KALANG RIVER HEALTH PLAN Foreword Kalang River Health Plan Our coastal waterways are under increasing pressure from population growth and change to the traditional low impact industries. -

Late Holocene Floodplain Processes and Post-European Channel

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year 2003 Late holocene floodplain processes and post-European channel dynamics in a partly confined valley of New South Wales Australia Timothy J. Cohen University of Wollongong Cohen, Timothy J., Late holocene floodplain processes and post-European channel dy- namics in a partly confined valley of New South Wales Australia, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Wollongong, 2003. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1931 This paper is posted at Research Online. 5. Post-European channel dynamics in the Bellinger valley CHAPTER 5 - POST-EUROPEAN CHANNEL DYNAMICS IN THE BELLINGER VALLEY 5.1 INTRODUCTION The Bellinger River, like many other systems in south-eastern Australia (see review by Rutherford, 2000), has undergone a series of planform and dimensional changes since European settlement. This chapter investigates the nature and timing of these changes and relates them to both the pre-European state of the channel and floodplain, along witii the rainfall and discharge patterns established in Chapter 3. The chapter consists of four main sections. Section 5.2 briefly outiines the methodological techniques used in this chapter, while Section 5.3 provides a historical assessment of channel and floodplain character in the Bellinger catchment. Sections 5.4 - 5.5 quantify the magnitude of change and present a summary of the evidence for cyclic channel changes. 5.2 METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH 5.2.1 Historical and anecdotal evidence for the BeUinger valley In order to determine the character of the Bellinger River and the surrounding floodplain environment at the time of settlement a number of historical data sources have been utilised. -

September 2015

Gleniffer Reserves Master Plan September 2015 Prepared by Fisher Design + Architecture in consultation with Mackenzie Pronk Architects | Jackie Amos Landscape Architect Caroline Desmond & Associates | Keiley Hunter Urban Planner Contents Chapter 1: Inception Chapter 4: Solutions, Strategies + Recommendations Overview 1 Earl Preston Reserve 19 Background 1 Timboon Road Connecting Trail 21 Executive Summary 2 Broken Bridge Reserve 24 Process 4 Arthur Keough Park 27 Objectives 4 Angel Gabriel Capararo Reserve 30 Principles 5 Design Precedent 32 Management 33 Chapter 2: Gathering + Interpretation Tourism 34 Community Engagement 6 Table: Management Directions & Recommendations 35 Cultural Meanings 8 Information and Education 36 Statutory Assessment 9 Signage 37 Chapter 3: Analysis Chapter 5: Implementation The Existing Condition of the Reserves 10 Table: Project Staging and Opinions of Probable Cost 41 - Earl Preston Reserve 13 - Timboon Road 14 Appendix 1: Community Consultation Report - Broken Bridge Reserve 15 - Arthur Keough Park 16 - Angel Gabriel Capararo Reserve 17 Chapter 1: Inception Gleniffer residents have reported Overview a large increase in visitation levels Background The Gleniffer Reserves are to a point where the environment In March 2014, Bellingen Brisbane situated along the Never and local quality of life are being Shire Council endorsed the Never River in the Bellingen significantly affected. Community Facilities & Open Space Infrastructure Section 94 Coffs Harbour Shire, approximately 10 The Gleniffer Valley is visited year Developer Contribution Plan kilometres northwest round, with peak periods during y 2014. This plan included funding w H the Christmas season, school c from the township of i f to establish a Master Plan and Dorrigo i c Bellingen, within one of holidays, and public holidays. -

Bellinger River Health Plan

BELLINGER RIVER HEALTH PLAN Bellingen Shire Council Title Bellinger River Health Plan Date of Publication March 2010 Copyright Copyright © 2010, Bellingen Shire Council. Along with any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this report may also be reproduced in part or whole for the purposes of study, research, review and/or general information provided clear acknowledgement of the source is made. Citation Bellingen Shire Council (2010). Bellinger River Health Plan. Bellinger Shire Council, NSW. ISBN 978 0 9807685 1 0 (Hard copy) ISBN 978 0 9807685 0 3 (Digital copy) Digital Copy Access This report can be accessed and downloaded on line at www.bellingen.nsw.gov.au by following the Environment prompt to the Healthy Rivers Program. Disclaimer While every care has been taken to ensure that the information contained in this report is accurate, complete and current at the time of publication, no warranty is given or implied that it is free of error or omission. No liability is accepted for any material or financial loss, damage, cost or injury arising from the use of this report. Funding Support This report has been prepared by Bellingen Shire Council with financial assistance from the NSW Government through the Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water. This document does not necessarily reflect the opinions of the NSW Government or the Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water. Cover Image Bellinger River estuary Bellingen Shire Healthy Rivers Program Bellinger River Health Plan BELLINGER RIVER HEALTH PLAN BELLINGER RIVER HEALTH PLAN Foreword Bellinger River Health Plan Our coastal waterways are under increasing pressure from population growth and change to the traditional low impact industries. -

The Attribution of Changes in Streamflow to Climate and Land Use Change for 472 Catchments in the United States and Australia

The attribution of changes in streamflow to climate and land use change for 472 catchments in the United States and Australia Master’s Thesis T.C. Schipper Master’s Thesis T.C. Schipper i Master’s Thesis T.C. Schipper Master’s Thesis Final July 2017 Author: T.C. Schipper [email protected] www.linkedin.com/in/theo-schipper-1196b36a Supervising committee: Dr. ir. M.J. Booij University of Twente Department of Water Engineering and Management (WEM) H. Marhaento MSc University of Twente Department of Water Engineering and Management (WEM) Source front page image: National weather service. Retrieved March 13 2017, from http://water.weather.gov/ahps2/hydrograph.php?wfo=chs&gage=GIVS1 ii Master’s Thesis T.C. Schipper iii Master’s Thesis T.C. Schipper Summary Climate change and land use change are ongoing features which affect the hydrological regime by changing the rainfall partitioning into actual evapotranspiration and runoff. A data-based method has been previously developed to attribute changes in streamflow to climate and land use change. Since this method has not been often applied, a large sample attribution study by applying this method to catchments in different parts of the world will provide more insight in the water partitioning and will evaluate the attribution method. The results can be used by water managers of the studied catchments to obtain the main reason for changes in streamflow. The used method is applicable to a large sample set of catchments because it is a relatively fast method and it can provide quantitative results. The objective of this study is to apply a non-modelling attribution method to attribute changes in streamflow to climate change and land use change to a large sample set of catchments in different parts of the world and to evaluate the used method. -

Occurrence of the Mayfly Family Teloganodidae in Northern New South Wales

Australian Journal of Entomology (1999) 38, 96–98 Occurrence of the mayfly family Teloganodidae in northern New South Wales Bruce C Chessman1 and Andrew J Boulton2 1Centre for Natural Resources, Department of Land and Water Conservation, PO Box 3720, Parramatta, NSW 2124, Australia (Email: [email protected]). 2Division of Ecosystem Management, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia. Abstract Teloganodid mayfly nymphs, previously known in Australia only from south-eastern Queensland, have now been recorded from numerous localities in the coastal drainages of northern New South Wales (NSW) from the Barrington Tops district to the Richmond River system. The nymphs seem to be restricted to riffles in forest streams and occur over a wide altitudinal range with records up to 940 m. They appear identical to those of Austremerella picta Riek, but rearing to the adult is needed to be certain that they represent the same species. The apparent restriction of Australian Teloganodidae to southern Queensland and northern NSW poses a biogeographical puzzle. Key words biogeography, Ephemoptera, Teloganodidae. INTRODUCTION as part of the national river bioassessment program (the Monitoring River Health Initiative) has produced additional The family Teloganodidae, recently elevated from subfamily records of the family (NSW Environment Protection Author- status in the Ephemerellidae (McCafferty & Wang 1997), is a ity, unpubl. data), as have some student research projects curious component of the Australian mayfly fauna (Camp- (Paul Massey-Reed, unpubl. data; Sandra Grinter, unpubl. bell 1990). It is represented by a single species, Aus- data). The family has now been recorded from all of the tremerella picta Riek, which for most of the time since its major NSW coastal drainage basins from the Hunter north to description over 30 years ago (Riek 1963; Allen 1965) was the Queensland border (Table 1; Fig. -

Dorrigo National Park Plan of Management

DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service October 1998 This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for the Environment on 4 October 1998. Acknowledgements: This plan of management has been prepared by staff of the Dorrigo District Office of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Crown Copyright 1998. Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgement. ISBN 0 7310 7688 5 FOREWORD Dorrigo National Park has an area of 7 885 hectares and is located 4 kilometres east of Dorrigo township which in turn lies 590 kilometres by road from Sydney. Dorrigo township is the centre of the rich agricultural lands of the Dorrigo Plateau. The town of Bellingen lies 25 kilometres to the east of the park and is the main town servicing the Bellinger Valley. The mid-north coast is within one hours drive of the park with the increasing population of centres such as Coffs Harbour and Nambucca Heads an important factor in park use and management. Part of Dorrigo Mountain was first protected in 1901. The area of reserved lands was progressively enlarged and granted increased protection until in 1967 when it was reserved under the National Parks and Wildlife Act, 1967 as a State Park. Under the National Parks and Wildlife Act of 1974 Dorrigo State Park was accorded national park status. In 1986 it was incorporated in the World Heritage List as one of the Sub-tropical and Warm Temperate Rainforest Parks of Eastern Australia, now known as the Central Eastern Rainforest Reserves of Australia. Dorrigo National Park is one of an important group of conservation areas on the Great Escarpment which include New England, Guy Fawkes River, Cathedral Rocks and Oxley Wild Rivers National Parks and Mount Hyland and Guy Fawkes River Nature Reserves. -

Bellingen Shire Development Control Plan 2017

BELLINGEN SHIRE DEVELOPMENT CONTROL PLAN 2017 Table of Amendments Amendment Date Date Adopted Commenced Minor review of DCP - DCP 2017 replaces 22 November 2017 6 December 2017 DCP 2010 Bellingen Shire Development Control Plan 2017 Chapter 1 Single Dwellings Table of Contents 1.1 Aims .................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Where This Chapter Applies .................................................................................... 4 1.3 When this Chapter Applies ....................................................................................... 4 1.4 Variations ................................................................................................................. 4 1.5 Definitions ................................................................................................................ 4 1.6 Development Criteria ............................................................................................... 5 1.6.1 Setbacks from boundaries ................................................................................. 5 1.6.2 Buffers to adjoining land uses, areas of environmental constraint or risk .......... 6 1.6.3 The building height plane envelope ................................................................... 6 1.6.4 Design controls ................................................................................................. 8 1.6.5 Landscaping ..................................................................................................... -

Extension of Unimpaired Monthly Streamflow Data and Regionalisation of Parameter Values to Estimate Streamflow in Ungauged Catchments

National Land and Water Resources Audit Theme 1-Water Availability Extension of Unimpaired Monthly Streamflow Data and Regionalisation of Parameter Values to Estimate Streamflow in Ungauged Catchments Centre for Environmental Applied Hydrology The University of Melbourne Murray C. Peel Francis H.S. Chiew Andrew W. Western Thomas A. McMahon July 2000 Summary This project is carried out by the Centre for Environmental Applied Hydrology at the University of Melbourne as part of the National Land and Water Resources Audit Project 1 in Theme 1 (Water Availability). The objectives of the project are to extend unimpaired streamflow data for stations throughout Australia and to relate the model parameters to measurable catchment characteristics. The long time series of streamflow data are important for both research and management of Australia’s hydrological and ecological systems. A simple conceptual daily rainfall-runoff model, SIMHYD, is used to extend the streamflow data. The model estimates streamflow from daily rainfall and areal potential evapotranspiration data. The parameters in the model are first calibrated against the available historical streamflow data. The optimised parameter values are then used to estimate monthly streamflow from 1901-1998. The modelling is carried out on 331 catchments across Australia, most of them located in the more populated and important agricultural areas in eastern and south-east Australia. These catchments are unimpaired, have at least 10 years of streamflow data and catchment areas between 50 km2 and 2000 km2. The model calibration and cross-validation analyses carried out in this project indicate that SIMHYD can estimate monthly streamflow satisfactorily for most of the catchments. -

BELLINGER River System LANDHOLDER BOOKLET

BELLINGER RIVER SYSTEM LANDHOLDER BOOKLET BEST PRACTICE FOR A HEALTHY RIVER Acknowledgements This booklet has been produced by Bellinger Landcare with funding received from the NSW Environmental Trust, in partnership with: • Bellingen Shire Council • North Coast Local Land Services • Bellinger River Freshwater Action Group • Office of Environment and Heritage • Western Sydney University • Muurrbay Aboriginal Language and Cultural Centre Thank you to all project partners for their input into the booklet and especially the Orara Valley RiverCare Groups Management Committee Inc. and Coffs Harbour City Council for the use of their booklet as a template. Thank you to Envite for the use of their photographs. Thank you to the artist Jackson Rae for use of ‘George’ - the turtle mascot featured on the front of this booklet. Bellinger Landcare Incorporated. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed as Attribution-Share-Alike under http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. You may copy, adapt or modify and distribute this work, provided that you credit the author, the title and the licence the work is under. Any new work produced using this material must be made available under the same terms. Contact: www.bellingerlandcare.org.au Bellinger Landcare Inc. (BLI) 1a Oak Street, Bellingen NSW 2454 Phone: (02) 6655 0588 The documented may be cited as: Bellinger River System Landholder Booklet, Bellinger Landcare 2016. Compiled and edited by Natasha English, Amanda Norman and Kylie Brooks Design and layout: Dee Rogers and Kylie Brooks Disclaimer: This booklet was prepared by BLI staff in consultation with the listed stakeholders and other professionals on the basis of available information.