The Battlefield Treasure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

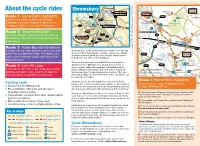

About the Cycle Rides

Sundorne Harlescott Route 45 Rodington About the cycle rides Shrewsbury Sundorne Mercian Way Heath Haughmond to Whitchurch START Route 1 Abbey START Route 2 START Route 1 Home Farm Highlights B5067 A49 B5067 Castlefields Somerwood Rodington Route 81 Gentle route following Route 81 through Monkmoor Uffington and Upton Magna to Home Farm, A518 Pimley Manor Haughmond B4386 Hill River Attingham. Option to extend to Rodington. Town Centre START Route 3 Uffington Roden Kingsland Withington Route 2 Around Attingham Route 44 SHREWSBURY This ride combines some places of interest in Route 32 A49 START Route 4 Sutton A458 Route 81 Shrewsbury with visits to Attingham Park and B4380 Meole Brace to Wellington A49 Home Farm. A5 Upton Magna A5 River Tern Walcot Route 3 Acton Burnell Adventure © Crown copyright and database rights 2012 Ordnance Survey 100049049 A5 A longer ride for more experienced cyclists with Shrewsbury is a very attractive historic market town nestled in a loop of the River Severn. The town centre has a largely Berwick Route 45 great views of Wenlock Edge, The Wrekin and A5064 Mercian Way You are not permitted to copy, sub-licence, distribute or sell any of this data third parties in form unaltered medieval street plan and features several timber River Severn Wharf to Coalport B4394 visits to Acton Burnell Castle and Venus Pool framed 15th and 16th century buildings. Emstrey Nature Reserve Home Farm The town was founded around 800AD and has played a B4380 significant role in British history, having been the site of A458 Attingham Park Uckington Route 4 Lyth Hill Loop many conflicts, particularly between the English and the A rewarding ride, with a few challenging climbs Welsh. -

The Life and Death of Richard Yea-And-Nay

The Life and Death of Richard Yea-And-Nay By Maurice Hewlett The Life and Death of Richard Yea-and-Nay CHAPTER I OF COUNT RICHARD, AND THE FIRES BY NIGHT I choose to record how Richard Count of Poictou rode all through one smouldering night to see Jehane Saint-Pol a last time. It had so been named by the lady; but he rode in his hottest mood of Nay to that, yet careless of first or last so he could see her again. Nominally to remit his master's sins, though actually (as he thought) to pay for his own, the Abbot Milo bore him company, if company you can call it which left the good man, in pitchy dark, some hundred yards behind. The way, which was long, led over Saint Andrew's Plain, the bleakest stretch of the Norman march; the pace, being Richard's, was furious, a pounding gallop; the prize, Richard's again, showed fitfully and afar, a twinkling point of light. Count Richard knew it for Jehane's torch, and saw no other spark; but Milo, faintly curious on the lady's account, was more concerned with the throbbing glow which now and again shuddered in the northern sky. Nature had no lamps that night, and made no sign by cry of night-bird or rustle of scared beast: there was no wind, no rain, no dew; she offered nothing but heat, dark, and dense oppression. Topping the ridge of sand, where was the Fosse des Noyées, place of shameful death, the solitary torch showed a steady beam; and there also, ahead, could be seen on the northern horizon that rim of throbbing light. -

Tna Prob 11/95/237

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES PROB 11/95/237 1 ________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY: The document below is the Prerogative Court of Canterbury copy of the last will and testament, dated 14 February 1598 and proved 24 April 1600, of Oxford’s half-sister, Katherine de Vere, who died on 17 January 1600, aged about 60. She married Edward Windsor (1532?-1575), 3rd Baron Windsor, sometime between 1553 and 1558. For his will, see TNA PROB 11/57/332. The testatrix’ husband, Edward Windsor, 3rd Baron Windsor, was the nephew of Roger Corbet, a ward of the 13th Earl of Oxford, and uncle of Sir Richard Newport, the owner of a copy of Hall’s Chronicle containing annotations thought to have been made by Shakespeare. The volume was Loan 61 in the British Library until 2007, was subsequently on loan to Lancaster University Library until 2010, and is now in the hands of a trustee, Lady Hesketh. According to the Wikipedia entry for Sir Richard Newport, the annotated Hall’s Chronicle is now at Eton College, Windsor. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Newport_(died_1570) Newport's copy of his chronicle, containing annotations sometimes attributed to William Shakespeare, is now in the Library at Eton College, Windsor. For the annotated Hall’s Chronicle, see also the will of Sir Richard Newport (d. 12 September 1570), TNA PROB 11/53/456; Keen, Alan and Roger Lubbock, The Annotator, (London: Putnam, 1954); and the Annotator page on this website: http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/annotator.html For the will of Roger Corbet, see TNA PROB 11/27/408. -

Tna Prob 11/27/408

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES PROB 11/27/408 1 ________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY: The document below is the Prerogative Court of Canterbury copy of the will, dated 27 November 1538 and proved 1 February 1539, of Roger Corbet (1501/2 – 20 December 1538), ward of John de Vere (1442-1513), 13th Earl of Oxford, and uncle of Sir Richard Newport (d. 12 September 1570), the owner of a copy of Hall’s Chronicle containing annotations thought to have been made by Shakespeare. The volume was Loan 61 in the British Library until 2007, was subsequently on loan to Lancaster University Library until 2010, and is now in the hands of a trustee, Lady Hesketh. According to the Wikipedia entry for Sir Richard Newport, the annotated Hall’s Chronicle is now at Eton College, Windsor. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Newport_(died_1570) Newport's copy of his chronicle, containing annotations sometimes attributed to William Shakespeare, is now in the Library at Eton College, Windsor. For the annotated Hall’s Chronicle, see also the will of Sir Richard Newport (d. 12 September 1570), TNA PROB 11/53/456; Keen, Alan and Roger Lubbock, The Annotator, (London: Putnam, 1954); and the Annotator page on this website: http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/annotator.html FAMILY BACKGROUND For the testator’s family background, see the pedigree of Corbet in Burke, John, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. III, (London: Henry Colburn, 1836), pp. 189-90 at: https://archive.org/stream/genealogicalhera03burk#page/188/mode/2up See also the pedigree of Corbet in Grazebrook, George, and John Paul Rylands, eds., The Visitation of Shropshire Taken in the Year 1623, Part I, (London: Harleian Society, 1889), Vol. -

MORETON CORBET Written Primarily by Barbara Coulton 1989

MORETON CORBET Written primarily by Barbara Coulton 1989 EARLY HISTORY There has been a settlement at Moreton at least since Saxon, even Roman times and it lies on the Roman road from Chester to Wroxeter. The Domesday Book (1086) records that Moreton was held by Thorold, from whom it was held by Hunning and his brother since before 1066. Another Saxon family, that of Thoret, came to have Moreton, under Robert fitz Turold. In the time of his descendant, Peter fitz Toret, the chapel at Moreton - a subsidiary of the church of St Mary at Shawbury (a Saxon foundation) - was granted, with St Mary's and its other chapels, to Haughmond Abbey, c. 1150. The north and south walls of the present church may date back to this time. Charters of Haughmond were attested by Peter fitz Toret and his sons, the second of whom, Bartholomew, inherited Moreton Toret, as it was then known. Witnesses to a charter of 1196 include Bartholomew de Morton and Richard Corbet of Wattlesborough, a small fortress in the chain guarding the frontier with Wales. He was a kinsman of the Corbets of Caus Castle, barons there from soon after the Norman conquest; Richard Corbet held Wattlesborough from his kinsman, owing him knight service each year, or when a campaign made it necessary. Richard Corbet married Bartholomew's daughter Joanna, heiress of Moreton, and their son, another RICHARD CORBET, inherited both Wattlesborough and Moreton. He married Petronilla, Lady of Booley and Edgbolton; their son ROBERT CORBET was of full age and in possession of his estates by 1255. -

Curriculum Vitae Note: This Document Is Divided Into Two Main Parts

1/47 Curriculum Vitae Note: this document is divided into two main parts. The first one covers the scientific and academic Philippe Pasquier dimension of my scholarly work while the second one (starting page 34) addresses the artistic dimension of Last updated on January 7, 2021. my research practice. This divide, introduced to facilitate reading, is somewhat artificial as these are often in synergy. Personal Data Work address School of Interactive Arts and Technology (SIAT), Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology, Email: [email protected] Simon Fraser University, http://www.sfu.ca/pasquier 250-13450, 102 Avenue, Surrey +1 778 989 1240 V3T 0A3, BC, Canada Citizenship Languages Canadian, French English, French (fluent) Spanish (beginner) Current Position Associate Professor, School of Interactive Art and Technology (SIAT), Simon Fraser University (SFU). Associate Dean Academic, Faculty of Communication Arts and Technology (FCAT), SFU. Academic Qualifications 2001-2005 Ph.D. DAMAS [Dialogue, Agent and Multi-Agents Systems] Laboratory, Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering, Laval University, Québec, Canada. Fields: Artificial Intelligence and Cognitive Sciences Thesis: Modelling the Cognitive Dimension of Agent Communication Supervisor: Prof. Brahim Chaib-draa Date: defended on the 30th of June 2005. Keywords: artificial intelligence, machine learning, multi-agent systems, agent architecture, social commitments, pragmatics, cognitive coherence, dialogue modelling. Graduate Courses: Machine Learning, Multi-agent Systems, Readings in Social Psychology 2000-2001 DEA (M.Sc.) SUPAERO [Aerospace Institute], UPS [Paul Sabatier University], ENSEEIHT [National Superior School of Electrotechnics, Electronics, Data processing, Hydraulics and Telecommunications], Toulouse, France. Field: Artificial Intelligence: Knowledge Representation and Formalization of Reasoning Thesis : Conflict and Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence Supervisor: Prof. -

Download William Jenyns' Ordinary, Pdf, 1341 KB

William Jenyns’ Ordinary An ordinary of arms collated during the reign of Edward III Preliminary edition by Steen Clemmensen from (a) London, College of Arms Jenyn’s Ordinary (b) London, Society of Antiquaries Ms.664/9 roll 26 Foreword 2 Introduction 2 The manuscripts 3 Families with many items 5 Figure 7 William Jenyns’ Ordinary, with comments 8 References 172 Index of names 180 Ordinary of arms 187 © 2008, Steen Clemmensen, Farum, Denmark FOREWORD The various reasons, not least the several german armorials which were suddenly available, the present work on the William Jenyns Ordinary had to be suspended. As the german armorials turned out to demand more time than expected, I felt that my preliminary efforts on this english armorial should be made available, though much of the analysis is still incomplete. Dr. Paul A. Fox, who kindly made his transcription of the Society of Antiquaries manuscript available, is currently working on a series of articles on this armorial, the first of which appeared in 2008. His transcription and the notices in the DBA was the basis of the current draft, which was supplemented and revised by comparison with the manuscripts in College of Arms and the Society of Antiquaries. The the assistance and hospitality of the College of Arms, their archivist Mr. Robert Yorke, and the Society of Antiquaries is gratefully acknowledged. The date of this armorial is uncertain, and avaits further analysis, including an estimation of the extent to which older armorials supplemented contemporary observations. The reader ought not to be surprised of differences in details between Dr. -

Election of Chicago Metropolitan Canceled

S O C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ nd W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ E ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald 10 2 N anniversa ry www.thenationalherald.com A wEEkly GREEk-AmERICAN PuBlICATION 1915-2017 VOL. 20, ISSUE 1031 July 15-21, 2017 c v $1.50 PBS Series This is Election of Chicago Metropolitan Canceled America Visits Greece Ecumenical Highlights NHS Patriarchate cites incomplete list of TNH Staff Marcus Family Foundation, the candidates National Hellenic Society WASHINGTON, DC – This is (NHS), American College of America & The World is a series Greece (ACG), and the Heritage By Theodore Kalmoukos hosted by Dennis Wholey, a Greece Program will be high - journalist and bestselling author lighted in Part II on Sunday, July NEW YORK – The election of with over 40 years of broadcast 16 at 10 PM. The episode will Bishop Sevastianos of Zela as experience. The weekly series feature interviews of several the new Metropolitan of covers international affairs and Heritage Greece student partic - Chicago was canceled by the is produced in Washington, DC, ipants and American College of Holy Synod of the Ecumenical featuring countries around the Greece President, David Horner. Patriarchate. The election was world. Greece Today – Part II fea - scheduled to take place on The series is broadcast na - tures Greece’s economy and Thursday, July 13 at the Phanar. tionally on public television and debt crisis along with the The National Herald has PBS stations, and it is distrib - refugee crisis which are dis - learned that the unexpected uted internationally by Voice of cussed during a visit to Athens. -

SHROPSHIRE WAY SOUTH SECTION About Stage 10A: Wellington to Haughmond 12 Miles

SHROPSHIRE WAY SOUTH SECTION About Stage 10a: Wellington to Haughmond 12 miles Wellington Market Square Wellington Carved owl at Haughmond Hill Instead of by-passing Wellington the Shropshire Way now goes through the centre of this Haughmond Hill historic market town. Few vestiges remain of its medieval past, the fortunes of the inhabitants After the climb it is worth taking the path to the having been influenced by the ever changing viewpoint for a good panorama of Shrewsbury economic climate. From livestock markets, light with the Shropshire Hills beyond. There are engineering and toy manufacturing to brewing the remains of a hill fort on a small mound and and mining, the townscape of Wellington has the point from which Queen Eleanor, the wife changed to keep pace with new demands. The of Henry IV, is reputed to have watched the Telford New Town development threatened progress of the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403. Wellington’s independence in 1974 but in recent The site of the battle is about 2 miles to the years there has been a resurgence of local pride Northwest. and the market provides a magnet for visitors. It is possible to get information and a Dothill Nature Reserve unique sight of the quarry workings from a viewing platform on your way to the Forestry This tranquil reserve comprises three main Commission carpark. Refreshments are areas, Dothill Pool, Tee Lake and Beanhill Valley available here. each with its own special character. With lakes, streams, woods and open meadows, it is a haven for wildlife and provides habitats for diverse species. -

Shropshire Cycleway Shropshire

Leaflet edition: SCW5-1a/Feb2015 • Designed by MA Creative Limited www.macreative.co.uk Limited Creative MA by Designed • SCW5-1a/Feb2015 edition: Leaflet This leaflet © Shropshire Council 2015. Part funded by the Department for Transport for Department the by funded Part 2015. Council Shropshire © leaflet This www.bicyclesmart.co.uk 01743 537124 01743 07528 785844 07528 Newport SY3 8JY SY3 Bicycle Smart Bicycle 20 Frankwell, Shrewsbury Shrewsbury Frankwell, 20 (MTB specialist) (MTB Trailhead The www.pjcyclerepairs.co.uk www.pjcyclerepairs.co.uk 07722 530531 07722 www.hawkcycles.co.uk Condover 01743 344554 01743 Repairs Cycle PJ SY1 2BB SY1 Shrewsbury www.bicyclerepairservices.co.uk www.bicyclerepairservices.co.uk 15 Castle Street Castle 15 07539 268741 07539 Hawk Cycles Hawk Broseley Bicycle Repair Services Services Repair Bicycle www.urbanbikesuk.co.uk 01686 625180 01686 www.cycletechshrewsbury.co.uk www.cycletechshrewsbury.co.uk 07828 638132 638132 07828 07712 183148 07712 Shrewsbury SY1 1HX SY1 Shrewsbury Stapleton Shrewsbury Market Hall Market Shrewsbury Cycle Tech Shrewsbury Shrewsbury Tech Cycle Unit 9-10, 9-10, Unit Urban Bikes UK Bikes Urban www.gocycling-shropshire.com www.gocycling-shropshire.com 07950 397335 07950 www.shrewsburycycles.co.uk Go Cycling Go 01743 232061 01743 SY1 4BE SY1 Mobile bike mechanics bike Mobile Shrewsbury Road, Ditherington 43 Cyclelife Shrewsbury Cyclelife www.halfords.com www.stanscycles.co.uk www.stanscycles.co.uk to Shropshire. Shropshire. to 01743 270277 01743 01743 343775 01743 attractive and -

Shropshire Transactions Vol. 85

Shropshire History and Archaeology Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society (incorporating the Shropshire Parish Register Society) VOLUME LXXXV edited by D. T. W. Price SHREWSBURY 2010 (ISSUED IN 2011) © Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society. Produced and printed by 4word Ltd., Bristol COUNCIL AND OFFICERS 1 DECEMBER 2011 President SIR NEIL COSSONS, O.B.E., M.A., F.S.A. Vice-Presidents M. UNA REES, B.A., PH.D. B. S. TRINDER, M.A., PH.D., F.S.A. ERNIE JENKS MADGE MORAN, F.S.A. Elected Members NIGEL BAKER, B.A., PH.D., M.I.F.A., F.S.A. MARY F. MCKENZIE, M.A., M.AR.AD. FRANCESCA BUMPUS, M.A., PH.D. PENNY WARD, M.A., M.I.F.A. NEIL CLARKE, B.A. ROGER WHITE, B.A., PH.D., M.I.F.A. ROBERT CROMARTY, B.A. ANDY WIGLEY, B.SC., M.A., P.C.H.E., PH.D. Chairman and Acting Hon. Treasurer JAMES LawsON, M.A., Westcott Farm, Pontesbury, Shrewsbury SY5 0SQ Hon. Secretary and Hon. Publications Secretary G. C. BAUGH, M.A., F.S.A., Glebe House, Vicarage Road, Shrewsbury SY3 9EZ Hon. Gift-Aid Secretary B. SHERRatt, 11 Hayton View, Ludlow SY8 2NU Hon. Membership Secretary W. F. HODGES, Westlegate, Mousecroft Lane, Shrewsbury SY3 9DX Hon. Editor THE REVD. CANON D. T. -

2008 International List of Protected Names

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities _________________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Avril / April 2008 Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Derby, Oaks, Saint Leger (Irlande/Ireland) Premio Regina Elena, Premio Parioli, Derby Italiano, Oaks (Italie/Italia)