Evaluation of Character Displacement Among Plants in Two Tropical Pollination Guilds 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Monocotiledóneas Y Pteridófitos De La Planada, Colombia

Biota Colombiana ISSN: 0124-5376 [email protected] Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos "Alexander von Humboldt" Colombia Ramírez Padilla, Bernardo; Mendoza Cifuentes, Humberto Monocotiledóneas y Pteridófitos de La Planada, Colombia Biota Colombiana, vol. 3, núm. 2, diciembre, 2002, pp. 285-295 Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos "Alexander von Humboldt" Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=49103204 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BiotaRamírez-P Colombiana & Mendoza-C 3 (2) 285 - 295, 2002 Monocots and Fern-allies of La Planada, Colombia -285 Monocotiledóneas y Pteridófitos de La Planada, Colombia Bernardo Ramírez-Padilla1 y Humberto Mendoza-Cifuentes2 1 Universidad del Cauca, Herbario CAUP, A.A. 1113, Popayán, Colombia. [email protected] 2 Instituto Alexander von Humboldt, A.A. 8693 Bogotá D.C., Colombia. [email protected] Palabras Clave: Flora, Bosque Nublado, Los Andes, Colombia, Lista de Especies La Planada es una reserva natural privada y un centro La mayoría de los registros del presente listado provienen de de investigación biológica de gran importancia en Colom- colecciones realizadas en la altiplanicie de la Reserva entre bia. Se localiza en la vertiente Pacífica de Los Andes colom- los 1800-1900 m de altitud. En esta área se encuentra vegeta- bianos, Municipio de Ricaurte, departamento de Nariño, ción de bosque maduro y bosque en avanzado estado de cerca de la frontera con el Ecuador, entre los 1500 y 2100 m, regeneración (más de 15 años). -

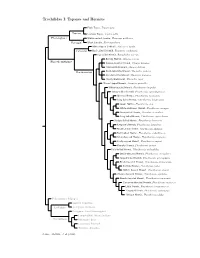

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Bulletin Biological Assessment Boletín RAP Evaluación Biológica

Rapid Assessment Program Programa de Evaluación Rápida Evaluación Biológica Rápida de Chawi Grande, Comunidad Huaylipaya, Zongo, La Paz, Bolivia RAP Bulletin A Rapid Biological Assessment of of Biological Chawi Grande, Comunidad Huaylipaya, Assessment Zongo, La Paz, Bolivia Boletín RAP de Evaluación Editores/Editors Biológica Claudia F. Cortez F., Trond H. Larsen, Eduardo Forno y Juan Carlos Ledezma 70 Conservación Internacional Museo Nacional de Historia Natural Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de La Paz Rapid Assessment Program Programa de Evaluación Rápida Evaluación Biológica Rápida de Chawi Grande, Comunidad Huaylipaya, Zongo, La Paz, Bolivia RAP Bulletin A Rapid Biological Assessment of of Biological Chawi Grande, Comunidad Huaylipaya, Assessment Zongo, La Paz, Bolivia Boletín RAP de Evaluación Editores/Editors Biológica Claudia F. Cortez F., Trond H. Larsen, Eduardo Forno y Juan Carlos Ledezma 70 Conservación Internacional Museo Nacional de Historia Natural Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de La Paz The RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment is published by: Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500 Arlington, VA USA 22202 Tel: +1 703-341-2400 www.conservation.org Cover Photos: Trond H. Larsen (Chironius scurrulus). Editors: Claudia F. Cortez F., Trond H. Larsen, Eduardo Forno y Juan Carlos Ledezma Design: Jaime Fernando Mercado Murillo Map: Juan Carlos Ledezma y Veronica Castillo ISBN 978-1-948495-00-4 ©2018 Conservation International All rights reserved. Conservation International is a private, non-proft organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of Conservation International or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Lições Das Interações Planta – Beija-Flor

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE BIOLOGIA JÉFERSON BUGONI REDES PLANTA-POLINIZADOR NOS TRÓPICOS: LIÇÕES DAS INTERAÇÕES PLANTA – BEIJA-FLOR PLANT-POLLINATOR NETWORKS IN THE TROPICS: LESSONS FROM HUMMINGBIRD-PLANT INTERACTIONS CAMPINAS 2017 JÉFERSON BUGONI REDES PLANTA-POLINIZADOR NOS TRÓPICOS: LIÇÕES DAS INTERAÇÕES PLANTA – BEIJA-FLOR PLANT-POLLINATOR NETWORKS IN THE TROPICS: LESSONS FROM HUMMINGBIRD-PLANT INTERACTIONS Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Biologia da Universidade Estadual de Campinas como parte dos requisitos exigidos para a obtenção do Título de Doutor em Ecologia. Thesis presented to the Institute of Biology of the University of Campinas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Ecology. ESTE ARQUIVO DIGITAL CORRESPONDE À VERSÃO FINAL DA TESE DEFENDIDA PELO ALUNO JÉFERSON BUGONI E ORIENTADA PELA DRA. MARLIES SAZIMA. Orientadora: MARLIES SAZIMA Co-Orientador: BO DALSGAARD CAMPINAS 2017 Campinas, 17 de fevereiro de 2017. COMISSÃO EXAMINADORA Profa. Dra. Marlies Sazima Prof. Dr. Felipe Wanderley Amorim Prof. Dr. Thomas Michael Lewinsohn Profa. Dra. Marina Wolowski Torres Prof. Dr. Vinícius Lourenço Garcia de Brito Os membros da Comissão Examinadora acima assinaram a Ata de Defesa, que se encontra no processo de vida acadêmica do aluno. DEDICATÓRIA À minha família por me ensinar o amor à natureza e a natureza do amor. Ao povo brasileiro por financiar meus estudos desde sempre, fomentando assim meus sonhos. EPÍGRAFE “Understanding patterns in terms of the processes that produce them is the essence of science […]” Levin, S.A. (1992). The problem of pattern and scale in ecology. Ecology 73:1943–1967. AGRADECIMENTOS Manifestar a gratidão às tantas pessoas que fizeram parte direta ou indiretamente do processo que culmina nesta tese não é tarefa trivial. -

Diversity and Levels of Endemism of the Bromeliaceae of Costa Rica – an Updated Checklist

A peer-reviewed open-access journal PhytoKeys 29: 17–62Diversity (2013) and levels of endemism of the Bromeliaceae of Costa Rica... 17 doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.29.4937 CHECKLIST www.phytokeys.com Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Diversity and levels of endemism of the Bromeliaceae of Costa Rica – an updated checklist Daniel A. Cáceres González1,2, Katharina Schulte1,3,4, Marco Schmidt1,2,3, Georg Zizka1,2,3 1 Abteilung Botanik und molekulare Evolutionsforschung, Senckenberg Forschungsinstitut Frankfurt/Main, Germany 2 Institut Ökologie, Evolution & Diversität, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt/Main, Germany 3 Biodive rsität und Klima Forschungszentrum (BiK-F), Frankfurt/Main, Germany 4 Australian Tropical Herbarium & Center for Tropical Biodiversity and Climate Change, James Cook University, Cairns, Australia Corresponding author: Daniel A. Cáceres González ([email protected]) Academic editor: L. Versieux | Received 1 March 2013 | Accepted 28 October 2013 | Published 11 November 2013 Citation: González DAC, Schulte K, Schmidt M, Zizka G (2013) Diversity and levels of endemism of the Bromeliaceae of Costa Rica – an updated checklist. PhytoKeys 29: 17–61. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.29.4937 This paper is dedicated to the late Harry Luther, a world leader in bromeliad research. Abstract An updated inventory of the Bromeliaceae for Costa Rica is presented including citations of representa- tive specimens for each species. The family comprises 18 genera and 198 species in Costa Rica, 32 spe- cies being endemic to the country. Additional 36 species are endemic to Costa Rica and Panama. Only 4 of the 8 bromeliad subfamilies occur in Costa Rica, with a strong predominance of Tillandsioideae (7 genera/150 spp.; 75.7% of all bromeliad species in Costa Rica). -

Differential Iridoid Production As Revealed by a Diversity Panel of 84 Cultivated and Wild Blueberry Species

RESEARCH ARTICLE Differential iridoid production as revealed by a diversity panel of 84 cultivated and wild blueberry species Courtney P. Leisner1*, Mohamed O. Kamileen2, Megan E. Conway1, Sarah E. O'Connor2, C. Robin Buell1 1 Department of Plant Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States of America, 2 Department of Biological Chemistry, The John Innes Centre, Norwich, United Kingdom a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Cultivated blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum, Vaccinium angustifolium, Vaccinium darro- wii, and Vaccinium virgatum) is an economically important fruit crop native to North America and a member of the Ericaceae family. Several species in the Ericaceae family including OPEN ACCESS cranberry, lignonberry, bilberry, and neotropical blueberry species have been shown to pro- Citation: Leisner CP, Kamileen MO, Conway ME, duce iridoids, a class of pharmacologically important compounds present in over 15 plant O'Connor SE, Buell CR (2017) Differential iridoid families demonstrated to have a wide range of biological activities in humans including anti- production as revealed by a diversity panel of 84 cultivated and wild blueberry species. PLoS ONE cancer, anti-bacterial, and anti-inflammatory. While the antioxidant capacity of cultivated 12(6): e0179417. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. blueberry has been well studied, surveys of iridoid production in blueberry have been pone.0179417 restricted to fruit of a very limited number of accessions of V. corymbosum, V. angustifolium Editor: Yuepeng Han, Wuhan Botanical Garden, and V. virgatum; none of these analyses have detected iridoids. To provide a broader survey CHINA of iridoid biosynthesis in cultivated blueberry, we constructed a panel of 84 accessions rep- Received: April 4, 2017 resenting a wide range of cultivated market classes, as well as wild blueberry species, and Accepted: May 29, 2017 surveyed these for the presence of iridoids. -

Observations of Hummingbird Feeding Behavior at Flowers of Heliconia Beckneri and H

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 18: 133–138, 2007 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society OBSERVATIONS OF HUMMINGBIRD FEEDING BEHAVIOR AT FLOWERS OF HELICONIA BECKNERI AND H. TORTUOSA IN SOUTHERN COSTA RICA Joseph Taylor1 & Stewart A. White Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, Graham Kerr Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, CB23 6DH, UK. Observaciones de la conducta de alimentación de colibríes con flores de Heliconia beckneri y H. tortuosa en El Sur de Costa Rica. Key words: Pollination, sympatric, cloud forest, Cloudbridge Nature Reserve, Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy, Violet Sabrewing, Campylopterus hemileucurus, Green-crowned Brilliant, Heliodoxa jacula. INTRODUCTION sources in a single foraging bout (Stiles 1978). Interactions between closely related sympatric The flower preferences shown by humming- flowering plants may involve competition for birds (Trochilidae) are influenced by a com- pollinators, interspecific pollen loss and plex array of factors including their bill hybridization (e.g., Feinsinger 1987). These dimensions, body size, habitat preference and processes drive the divergence of genetically relative dominance, as influenced by age and based floral phenotypes that influence polli- sex, and how these interact with the morpho- nator assemblages and behavior. However, logical, caloric and visual properties of flow- floral convergence may be favored if the ers (e.g., Stiles 1976). increased nectar supplies and flower densities, Hummingbirds are the primary pollina- for example, increase the regularity and rate tors of most Heliconia species (Heliconiaceae) of flower visitation for all species concerned (Linhart 1973), which are medium to large (Schemske 1981). Sympatric hummingbird- clone-forming herbs that usually produce pollinated plants probably face strong selec- brightly colored floral bracts (Stiles 1975). -

Project Scientific Progress Report Study Site

Project Ecology of plant-hummingbird interactions along an elevational gradient Scientific Progress Report Project leader: Catherine Graham, Swiss Federal Research Institute Principal investigator: María Alejandra Maglianesi, Universidad Estatal a Distancia Coordinator: Emanuel Brenes Rodríguez, Universidad Estatal a Distancia Study site Las Nubes Biological Reserve York University San José, Costa Rica January, 2020 1 INTRODUCTION A primary aim of community ecology is to identify the processes that govern species assemblages across environmental gradients (McGill et al. 2006), allowing us to understand why biodiversity is non-randomly distributed on Earth. Mutualistic interactions such as those between plants and their animal pollinators are the major biodiversity component from which the integrity of ecosystems depends (Valiente-Banuet et al. 2015). The interdependence of plant and pollinators can be assessed using a network approach, which is a powerful tool to analyze the complexity of ecological systems (Ings et al. 2009), especially in highly diversified tropical regions. Mountain regions provide pronounced environmental gradients across relatively small spatial scales and have proved to be a suitable model system to investigate patterns and determinants of species diversity and community structure (Körner 2000, Sanders and Rahbek 2012). Although some studies have investigated the variation in plant–pollinator interaction networks across elevational gradients (Ramos-Jiliberto et al. 2010, Benadi et al. 2013), such studies are still scarce, particularly in the tropics. In the Neotropics, hummingbirds (Trochilidae) are considered to be effective pollinators (Castellanos et al. 2003). They have been classified into two distinct groups: hermits and non-hermits, which differ mainly in their elevational distribution and their level of specialization on floral resources, i.e., the proportion of floral resources available in the community that is used by species (Stiles 1978). -

The Best of Costa Rica March 19–31, 2019

THE BEST OF COSTA RICA MARCH 19–31, 2019 Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge © David Ascanio LEADERS: DAVID ASCANIO & MAURICIO CHINCHILLA LIST COMPILED BY: DAVID ASCANIO VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM THE BEST OF COSTA RICA March 19–31, 2019 By David Ascanio Photo album: https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidascanio/albums/72157706650233041 It’s about 02:00 AM in San José, and we are listening to the widespread and ubiquitous Clay-colored Robin singing outside our hotel windows. Yet, it was still too early to experience the real explosion of bird song, which usually happens after dawn. Then, after 05:30 AM, the chorus started when a vocal Great Kiskadee broke the morning silence, followed by the scratchy notes of two Hoffmann´s Woodpeckers, a nesting pair of Inca Doves, the ascending and monotonous song of the Yellow-bellied Elaenia, and the cacophony of an (apparently!) engaged pair of Rufous-naped Wrens. This was indeed a warm welcome to magical Costa Rica! To complement the first morning of birding, two boreal migrants, Baltimore Orioles and a Tennessee Warbler, joined the bird feast just outside the hotel area. Broad-billed Motmot . Photo: D. Ascanio © Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 The Best of Costa Rica, 2019 After breakfast, we drove towards the volcanic ring of Costa Rica. Circling the slope of Poas volcano, we eventually reached the inspiring Bosque de Paz. With its hummingbird feeders and trails transecting a beautiful moss-covered forest, this lodge offered us the opportunity to see one of Costa Rica´s most difficult-to-see Grallaridae, the Scaled Antpitta. -

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia Beckneri and H

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia beckneri and H. tortuosa at Cloudbridge Nature Reserve Joseph Taylor University of Glasgow The Hummingbird-Heliconia Project The hummingbird family (Trochilidae), endemic to the Neotropics, is remarkable not only for its beauty but also because of its ability to hover over a flower while feeding, its wing movements a blur. These lively birds require frequent, nutritious feeding to sustain their expenditure of energy, and some plants have evolved to attract and feed them in exchange for pollination services. Prominent among such plants are most species in the genus Heliconia (Heliconiaceae), which are medium to large clone-forming herbs with banana-like leaves (Stiles, 1975). The hummingbird-Heliconia interdependence is a good example of co- evolution, and this study is concerned with one aspect of this relationship. Since several species of hummingbird and Heliconia exist at Cloudbridge, a middle-elevation nature reserve in Costa Rica, we wondered whether particular species of Heliconia had evolved an attraction for particular hummingbird species, which might reduce the chances of hybridisation and pollen loss; or whether the plants compete for a variety of hummingbirds. At Cloudbridge, on the Pacific slope of southern Costa Rica’s Talamanca mountain range, Heliconia beckneri , an endangered species (website 1) restricted to this area and thought to be of hybrid origin (Daniels and Stiles, 1979; website 2), and H. tortuosa occur together. Stiles (1979) names the Green Hermit ( Phaethornis guy ) as the primary pollinator of both species and the Violet Sabrewing ( Campylopterus hemileucurus ) as the secondary pollinator of H. -

The Taxonomy of VACCINIUM Section RIGIOLEPIS (Vaccinieae, Ericaceae)

BLUMEA 50: 477– 497 Published on 14 December 2005 http://dx.doi.org/10.3767/000651905X622743 THE TAXONOMY OF VACCINIUM SECTION RIGIOLEPIS (VACCINIEAE, ERICACEAE) S.P. VANDER KLOET Department of Biology, Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia, B4P 2R6 Canada SUMMARY Vaccinium section Rigiolepis (Hook.f.) Sleumer is revised for the Flora Malesiana region. In the introduction a short history of the genus (section) and its defining characters are presented followed by comments about Sleumer’s classification for this section. Numerical techniques using features suggested by Sleumer on ‘indet’ specimens at Leiden counsel a more conservative approach to species delimitation and the resultant revision for this section recognizes thirteen species including three new taxa, viz., V. crinigrum, V. suberosum, and V. linearifolium. Lectotypes for V. borneense W.W. Sm. and V. leptanthum Miq. are also proposed. Key words: Vaccinium, Rigiolepis, Malesia, new species. INTRODUCTION Since its inception in 1876, the genus Rigiolepis Hook.f. has been a perennial candidate for the Rodney Dangerfield ‘No Respect’ Award. All the other SE Asian segregates of Vaccinieae, such as Agapetes D. Don, Dimorphanthera F. Muell., and Costera J.J. Sm. have gained widespread acceptance among botanists, but not so Rigiolepis where even the staunchest supporters, viz., Ridley (1922) and Smith (1914, 1935) could not agree on a common suite of generic characters for this taxon. Ridley (1922) argued that Rigiolepis could be separated from Vaccinium by its epiphytic habit, extra-axillary racemes and very small flowers. Unfortunately, neither small flowers nor the epiphytic habit are unique to Rigiolepis but are widespread in the Vaccinieae; indeed V. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed