Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

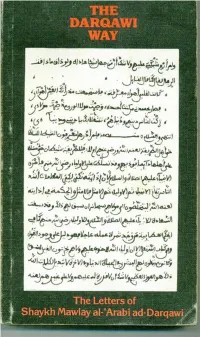

The-Darqawi-Way.Pdf

The Darqawi Way Moulay al-‘Arabi ad-Darqawi Letters from the Shaykh to the Fuqara' 1 First edition copyright Diwan Press 1979 Reprinted 1981 2 The Darqawi Way Letters from the Shaykh to the Fuqara' Moulay al-‘Arabi ad-Darqawi translated by Aisha Bewley 3 Contents Song of Welcome Introduction Foreword The Darqawi Way Isnad of the Tariq Glossary 4 A Song of Welcome Oh! Mawlay al-‘Arabi, I greet you! The West greets the West — Although the four corners are gone And the seasons are joined. In the tongue of the People I welcome you — the man of the time. Wild, in rags, with three hats And wisdom underneath them. You flung dust in the enemy’s face Scattering them by the secret Of a rare sunna the ‘ulama forgot. Oh! Mawlay al-‘Arabi, I love you! The Pole greets the Pole — The centre is everywhere And the circle is complete. We have danced with Darqawa, Supped at their table, yes, And much, much more, I And you have sung the same song, The song of the sultan of love. Oh! Mawlay al-‘Arabi, you said it! Out in the open you gave the gift. Men drank freely from your jug. The cup passed swiftly, dizzily — Until it came into my hand. I have drunk, I have drunk, I am drinking still, the game Is over and the work is done. What is left if it is not this? 5 This wine that is not air, Nor fire, nor earth, nor water. This diamond — I drink it! Oh! Mawlay al-‘Arabi, you greet me! There is no house in which I sit That you do not sit beside me. -

A SUFI ‘FRIEND of GOD’ and HIS ZOROASTRIAN CONNECTIONS: the Paradox of Abū Yazīd Al-Basṭāmī ______Kenneth Avery

SAJRP Vol. 1 No. 2 (July/August 2020) A SUFI ‘FRIEND OF GOD’ AND HIS ZOROASTRIAN CONNECTIONS: The Paradox of Abū Yazīd al-Basṭāmī ____________________________________________________ Kenneth Avery ABSTRACT his paper examines the paradoxical relation between the T famed Sufi ‘friend’ Abū Yazīd al-Basṭāmī (nicknamed Bāyazīd; d. 875 C.E. or less likely 848 C.E.) and his Zoroastrian connections. Bāyazīd is renowned as a pious ecstatic visionary who experienced dream journeys of ascent to the heavens, and made bold claims of intimacy with the Divine. The early source writings in both Arabic and Persian reveal a holy man overly concerned with the wearing and subsequent cutting of the non- Muslim zunnār or cincture. This became a metaphor of his constant almost obsessive need for conversion and reconversion to Islam. The zunnār also acts as a symbol of infidelity and his desire to constrict his lower ego nafs. The experience of Bāyazīd shows the juxtaposition of Islam with other faiths on the Silk Road in 9th century Iran, and despite pressures to convert, other religions were generally tolerated in the early centuries following the Arab conquests. Bāyazīd’s grandfather was said to be a Zoroastrian and the family lived in the Zoroastrian quarter of their home town Basṭām in northeast Iran. Bāyazīd shows great kindness to his non-Muslim neighbours who see in him the best qualities of Sufi Islam. The sources record that his saintliness influenced many to become Muslims, not unlike later Sufi missionaries among Hindus and Buddhists in the subcontinent. 1 Avery: Sufi Friend of God INTRODUCTION Bāyazīd’s fame as a friend of God is legendary in Sufi discourse. -

An Analysis of Al-Hakim Al-Tirmidhi's Mystical

AN ANALYSIS OF AL-HAKIM AL-TIRMIDHI’S MYSTICAL IDEOLOGY BASED ON BOOKS: BADʼU SHAANI AND SIRAT AL-AWLIYA Kazem Nasirizare, Ph.D. Candidate in Persian Language and Literature University of Zanjan, Iran Mehdi Mohabbati, Ph.D. Professor. at Department of Persian Language and Literature University of Zanjan Abstract. Abu Abdullah Muhammad bin Hasan bin Bashir Bin Harun Al Hakim Al-Tirmidhi, also called Al- Hakim Al-Tirmidhi, is a Persian mystic living in the 3rd century AH. He is important in the history of Persian literature and the Persian-Islamic mysticism due to several reasons. First, he is one of the first Persian mystics who has significant works in the field of mysticism. Second, early instances of Persian prose can be identified in his world and taking the time that he was living into consideration, the origins of post-Islam Persian prose can be seen in his writings. Third, his ideas have had significant impacts on Mysticism, Sufism, and consequently, in the Persian mystical literature; thus, understanding and analyzing his viewpoints and works is of significant importance for attaining a better picture of Persian mystical literature. The current study attempts to analyze Al-Tirmidhi’s mystical ideology based on his two books: Bad’u Shanni Abu Abdullah (The Beginning of Abu Abdullah’s Journey) and Sirat Al-Awliya (Road of the Saints). Al-Tirmidhi’s ideology is going to be explained through investigating and analyzing his viewpoints regarding the manner of starting a spiritual journey, the status of asceticism and austerity in a spiritual journey, transition from the ascetic school of Baghdad to the Romantic school of Khorasan. -

Ibn Ata Allah Al-Iskandari and Al-Hikam Al-‘Ata’Iyya in the Context of Spiritually-Oriented Psychology and Counseling

SPIRITUAL PSYCHOLOGY AND COUNSELING Received: November 13, 2017 Copyright © 2018 s EDAM Revision Received: May 2, 2018 eISSN: 2458-9675 Accepted: June 26, 2018 spiritualpc.net OnlineFirst: August 7, 2018 DOI 10.37898/spc.2018.3.2.0011 Original Article Ibn Ata Allah al-Iskandari and al-Hikam al-‘Ata’iyya in the Context of Spiritually-Oriented Psychology and Counseling Selami Kardaş1 Muş Alparslan University Abstract Ibn Ata Allah al-Iskandari was a Shadhili Sufi known for his work, al-Hikam al-‘Ata’iyya. Ibn Ata Allah, known for his influential oratorical style, sermons, and conversations, which deeply impacted the masses during his time, reflected these qualities in all his works, especially al-Hikam al-‘Ata’iyya. Along with this, finding information on the deepest topics of mysticism is possible in his works. His works address the basic concepts of mystical thinking, such as worship and obedience removed from hypocrisy and fame, resignation, surrender, limits, and hope. This study attempts to explain al-Iskandari’s life, works, mystical understanding, contribution to the world of thought, and concepts specifically addressed in his works, like worship and obedience apart from fame and hypocrisy, trust in God, surrender, limits, and hope. Together with this, the study focuses on the prospect of being able to address al-Iskandari and his work, al-Hikam al-‘Ata’iyya, in particular as a resource particular to spiritually-oriented psychology and psychological counseling through the context of psychology and psychological counseling. Keywords: Ibn Ata Allah al-Iskandari • Al-Hikam al-‘Ata’iyya • Spirituality • Psychology •Psychological counseling Manevi Yönelimli Psikoloji ve Danışma Bağlamında İbn Atâullah el-İskenderî ve el-Hikemü’l-Atâiyye Öz İbn Ataullah el-İskenderi, el-Hikemü’l-Atâiyye adlı eseriyle tanınan Şazelî sûfîdir. -

From Rabi`A to Ibn Al-Färich Towards Some Paradigms of the Sufi Conception of Love

From Rabi`a to Ibn al-Färich Towards Some Paradigms of the Sufi Conception of Love By Suleyman Derin ,%- Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy Department of Arabic and 1Viiddle Eastern Studies The University of Leeds The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own work and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. September 1999 ABSTRACT This thesis aims to investigate the significance of Divine Love in the Islamic tradition with reference to Sufis who used the medium of Arabic to communicate their ideas. Divine Love means the mutual love between God and man. It is commonly accepted that the Sufis were the forerunners in writing about Divine Love. However, there is a relative paucity of literature regarding the details of their conceptions of Love. Therefore, this attempt can be considered as one of the first of its kind in this field. The first chapter will attempt to define the nature of love from various perspectives, such as, psychology, Islamic philosophy and theology. The roots of Divine Love in relation to human love will be explored in the context of the ideas that were prevalent amongst the Sufi authors regarded as authorities; for example, al-Qushayri, al-Hujwiri and al-Kalabadhi. The second chapter investigates the origins Of Sufism with a view to establishing the role that Divine Love played in this. The etymological derivations of the term Sufi will be referred to as well as some early Sufi writings. It is an undeniable fact that the Qur'an and tladith are the bedrocks of the Islamic religion, and all Muslims seek to justify their ideas with reference to them. -

Cinema of Immanence: Mystical Philosophy in Experimental Media

CINEMA OF IMMANENCE: MYSTICAL PHILOSOPHY IN EXPERIMENTAL MEDIA By Mansoor Behnam A thesis submitted to the Cultural Studies Program In conformity with the requirements for The degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (May 2015) Copyright © Mansoor Behnam, 2015 Abstract This research-creation discovers the connection between what Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari termed as the Univocity of Being, and the Sufi and pantheistic concept of Unity of Being (wahdat al-wujud) founded by the Islamic philosopher/mystic Ibn al-‘Arabī(A.H. 560- 638/A.D. 1165-1240). I use the decolonizing historiography of the concept of univocity of being carried out by the scholar of Media Art, and Islamic Thoughts Laura U. Marks. According to Marks’ historiography, it was the Persian Muslim Polymath Abu ‘Ali al-Husayn ibn Sînâ (980-1037) who first initiated the concept of haecceity (thisness)--the basis of the univocity of being. The thesis examines transformative experimental cinema and video art from a mystical philosophical perspective (Sufism), and by defying binaries of East/West, it moves beyond naïve cosmopolitanism, to nuanced understanding of themes such as presence, proximity, self, transcendence, immanence, and becoming, in media arts. The thesis tackles the problem of Islamic aniconism, nonrepresentability, and inexpressibility of the ineffable; as it is reflected in the mystical/paradoxical concept of the mystical Third Script (or the Unreadable Script) suggested by Shams-i-Tabrīzī (1185- 1248), the spiritual master of Mawlana Jalal ad-Dīn Muhhammad Rūmī (1207-1273). I argue that the Third Script provides a platform for the investigation of the implications of the language, silence, unsayable, and non-representation. -

Download Date 26/09/2021 10:00:58

Ecstatic Religious Expression within Islam Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nettles Leavitt, Isolde Betty Blythe, 1950- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 10:00:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/558213 ECSTATIC RELIGIOUS EXPRESSION WITHIN ISLAM by Isolde Betty Blythe Nettles Leavitt Copyright ©Isolde Betty Blythe Nettles Leavitt 1993 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Near Eastern Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Masters of Arts In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 9 3 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: 'll P tt/r* J APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: William J. Wilson Professor ofiMkrale Eastern History 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My deepest gratude to Stephen Murray for his tireless efforts in the typing of this manuscript. -

An Anti-Ibn 'Arabī (D. 1240) Polemicist in Sixteenth- Century Ottoman Istanbul: Ibrāhīm Al-Ḥalabī (D.1549) and His Inte

Cankat Kaplan AN ANTI-IBN ‘ARABĪ (D. 1240) POLEMICIST IN SIXTEENTH- CENTURY OTTOMAN ISTANBUL: IBRĀHĪM AL-ḤALABĪ (D.1549) AND HIS INTERLOCUTORS MA Thesis in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies Central European University Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection AN ANTI-IBN ‘ARABĪ (D. 1240) POLEMICIST IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY OTTOMAN ISTANBUL: IBRĀHĪM AL-ḤALABĪ (D.1549) AND HIS INTERLOCUTORS by Cankat Kalpan (Turkey) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ___________________________ ________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest CEU eTD Collection May 2019 AN ANTI-IBN ‘ARABĪ (D. 1240) POLEMICIST IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY OTTOMAN ISTANBUL: IBRĀHĪM AL-ḤALABĪ (D.1549) AND HIS INTERLOCUTORS by Cankat Kaplan (Turkey) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. _____________________ ____________________ External Reader Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection AN ANTI-IBN ‘ARABĪ (D. 1240) POLEMICIST IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY OTTOMAN ISTANBUL: IBRĀHĪM AL-ḤALABĪ (D.1549) AND HIS INTERLOCUTORS by Cankat Kaplan (Turkey) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. -

Turkish Sufi Organizations and the Development of Islamic Education in Indonesia

Analisa Journal of Social Science and Religion Vol. 05 No. 01 July 2020 Website Journal : http://blasemarang.kemenag.go.id/journal/index.php/analisa DOI : https://doi.org/10.18784/analisa.v5i1.907 TURKISH SUFI ORGANIZATIONS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF ISLAMIC EDUCATION IN INDONESIA Firdaus Wajdi1 1Universitas Negeri Jakarta Jakarta, Indonesia Abstract [email protected] Sufism has contributed substantially in the development of Islam across the globe. It is also the case of Indonesia. Sufi preachers have been noticed as among the Paper received: 30 September 2019 early Muslims who conveyed and disseminate Islam in the Archipelago. This trend Paper revised: 11 –23 June 2020 seems to be repeated in this current Indonesian Islam. However, what is commonly Paper approved: 7 July 2020 unknown, Turkish organization also takes part in this current mode. Particularly, it is with the Islamic transnational organization from Turkey operating in Indonesia as the actors. This article aims at discussing the Sufi elements within three Turkish based transnational communities in Indonesian Islam and their contribution to Islamic education as part of Islamic development in the current Indonesia. This is a qualitative research to the topics within the three Turkish origin transnational Islamic organizations, namely the Jamaat Nur, the Fethullah Gülen Affiliated Movement, and the Suleymaniyah. This article will then argue that Sufism has continued to be one of the contributing factors for the development of Islam and in relation to that the Sufi elements within the three Turkish Transnational organizations also contribute to their acceptance in Indonesia. Overall, the Sufi elements have shaped the image and identity of the Turkish Muslims in developing the Islamic studies in Indonesia. -

Introducing Ibn 'Arabī's Book of Spiritual Advice

Introducing Ibn ‘Arabī’s Book of spiritual advice Author: James Winston Morris Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/4225 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Published in Journal of the Muhyiddīn Ibn ‘Arabī Society, vol. 28, pp. 1-17, 2000 Use of this resource is governed by the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons "Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States" (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/) Introducing Ibn 'Arabī's "Book of Spiritual Advice" James Winston Morris One of the misfortunes that can befall a true genius, perhaps most obviously in fields like music or poetry, is that the fame of their most celebrated masterpieces can easily obscure the extraordinary qualities of "lesser" works which - by any other hand - would surely be renowned in their own right. Certainly that has too often been the case with Ibn 'Arabī's Fusūs al-Hikam and his Futūhāt. Among the smaller treasures they have sometimes overshadowed is his remarkable book of spiritual aphorisms, the "Book of Spiritual Advice" (Kitāb al-Nasā'ih),1 a short treatise whose many extant manuscript copies and profusion of later titles reflects the great practical value placed on it by many generations of Sufi readers. Here we would like to offer a partial selection of some of the most accessible (and easily translatable) sayings from that work, which we hope to publish soon in a complete and more fully annotated version as part of a larger volume bringing together Ibn 'Arabi's shorter works of practical spiritual advice.2 1. -

Khan, Amina Kausar (2017) on Becoming Naught: Reading the Doctrine of Fana and Baqa in the Mathnawi of Jalal Al-Din Rumi

Khan, Amina Kausar (2017) On becoming naught: reading the doctrine of fana and baqa in the Mathnawi of Jalal al-Din Rumi. MTh(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8222/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] On Becoming Naught: Reading the doctrine of Fana and Baqa in the Mathnawi of Jalal al-Din Rumi AMINA KAUSAR KHAN BA (HONS) ENGLISH Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of MTh (Research) Theology and Religious Studies School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow April 2017 © Amina Khan, 2017 ABSTRACT Notwithstanding the abundance of scholarship on Rumi’s Mathnawi, in the Western world; the nature of the Sufi doctrine of self-annihilation (fana) and subsistence in God (baqa), in the poem, is a neglected area of research. Often misunderstood, or reduced to simply being one of the many themes in the Mathnawi, greater emphasis is placed on the concepts of Love, Unity and Ecstasy, as the central message. Equally, Rumi’s intention that the Mathnawi should be used as a training manual, and the formal design of the poem in this regard, is generally overlooked. -

Islām and Sūfism

Isl ām and S ūfism © Copyright 1991/2006 by Timothy Conway, Ph.D. Brief Overview (for more on specific persons, starting with Prophet Muhammad, see next section) [Note: The saying or writing of the names of Prophet Muhammad and the other prophets [Jesus, Abraham, et al.] and certain eminent saints, but most especially that of Prophet Muhammad, when spoken by pious Muslims are always followed by inclusion of the reverential saying, Sall-All āhu ‘alayhi wa sallam , “God’s peace and blessings be upon him” (sometimes abbreviated in English as p.b.u.h.). For ease of readability, I have omitted that pious custom here.] [Note: The official Muslim calendar, which I have also not used here, is based on the lunar year of 354 days, twelve months of 29 and 30 days, beginning with Prophet Muhammad’s emigration from Mecca to Med īna in 622. To compute a year in the Common Era (C.E. / A.D.) from a Muslim year (h.), multiply the Muslim year by 0.969 and add this to 622. Example: 300 h.= 912-3 CE; 600 h.= 1203-4 CE; 1300 h.= 1881-2 CE.] * * * * * * * * * * sl ām, meaning “submission to All āh/God,” was founded by Prophet Muhammad (571-632) and seen by his fast-growing community as God’s way of bringing a revealed religion to the Arabian people. It all I began one day in the year 610 CE, when Muhammad, who had been orphaned in youth and raised by a series of relatives to become a respected figure in the community, was with his wife Khad īja on Mt.