The Cromer Moraine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Share Report

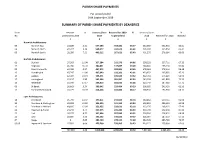

PARISH SHARE PAYMENTS For period ended 30th September 2019 SUMMARY OF PARISH SHARE PAYMENTS BY DEANERIES Dean Amount % Deanery Share Received for 2019 % Deanery Share % No Outstanding 2018 2019 to period end 2018 Received for 2018 received £ £ £ £ £ Norwich Archdeaconry 06 Norwich East 23,500 4.41 557,186 354,184 63.57 532,380 322,654 60.61 04 Norwich North 47,317 9.36 508,577 333,671 65.61 505,697 335,854 66.41 05 Norwich South 28,950 7.21 409,212 267,621 65.40 401,270 276,984 69.03 Norfolk Archdeaconry 01 Blofield 37,303 11.04 327,284 212,276 64.86 338,033 227,711 67.36 11 Depwade 46,736 16.20 280,831 137,847 49.09 288,484 155,218 53.80 02 Great Yarmouth 44,786 9.37 467,972 283,804 60.65 478,063 278,114 58.18 13 Humbleyard 47,747 11.00 437,949 192,301 43.91 433,952 205,085 47.26 14 Loddon 62,404 19.34 335,571 165,520 49.32 322,731 174,229 53.99 15 Lothingland 21,237 3.90 562,194 381,997 67.95 545,102 401,890 73.73 16 Redenhall 55,930 17.17 339,813 183,032 53.86 325,740 187,989 57.71 09 St Benet 36,663 9.24 380,642 229,484 60.29 396,955 243,433 61.33 17 Thetford & Rockland 31,271 10.39 314,266 182,806 58.17 300,933 192,966 64.12 Lynn Archdeaconry 18 Breckland 45,799 11.97 397,811 233,505 58.70 382,462 239,714 62.68 20 Burnham & Walsingham 63,028 15.65 396,393 241,163 60.84 402,850 256,123 63.58 12 Dereham in Mitford 43,605 12.03 353,955 223,631 63.18 362,376 208,125 57.43 21 Heacham & Rising 24,243 6.74 377,375 245,242 64.99 359,790 242,156 67.30 22 Holt 28,275 8.55 327,646 207,089 63.21 330,766 214,952 64.99 23 Lynn 10,805 3.30 330,152 196,022 59.37 326,964 187,510 57.35 07 Repps 0 0.00 383,729 278,123 72.48 382,728 285,790 74.67 03 08 Ingworth & Sparham 27,983 6.66 425,260 239,965 56.43 420,215 258,960 61.63 727,583 9.28 7,913,818 4,789,282 60.52 7,837,491 4,895,456 62.46 01/10/2019 NORWICH DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE LTD DEANERY HISTORY REPORT MONTH September YEAR 2019 SUMMARY PARISH 2017 OUTST. -

River Glaven State of the Environment Report

The River Glaven A State of the Environment Report ©Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative ©Evelyn Simak and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence Commons Licence © Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this C reative ©Oliver Dixon and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence Commons Licence Produced by Norfolk Biodiversity Information Service Spring 201 4 i Norfolk Biodiversity Information Service (NBIS) is a Local Record Centre holding information on species, GEODIVERSITY , habitats and protected sites for the county of Norfolk. For more information see our website: www.nbis.org.uk This report is available for download from the NBIS website www.nbis.org.uk Report written by Lizzy Oddy, March 2014. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank the following people for their help and input into this report: Mark Andrews (Environment Agency); Anj Beckham (Norfolk County Council Historic Environment Service); Andrew Cannon (Natural Surroundings); Claire Humphries (Environment Agency); Tim Jacklin (Wild Trout Trust); Kelly Powell (Norfolk County Council Historic Environment Service); Carl Sayer (University College London); Ian Shepherd (River Glaven Conservation Group); Mike Sutton-Croft (Norfolk Non-native Species Initiative); Jonah Tosney (Norfolk Rivers Trust) Cover Photos Clockwise from top left: Wiveton Bridge (©Evelyn Simak and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); Glandford Ford (©Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); River Glaven above Glandford (©Oliver Dixon and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); Swan at Glandford Ford (© Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence). ii CONTENTS Foreword – Gemma Clark, 9 Chalk Rivers Project Community Involvement Officer. -

Norfolk Through a Lens

NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service 2 NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service History and Background The systematic collecting of photographs of Norfolk really began in 1913 when the Norfolk Photographic Survey was formed, although there are many images in the collection which date from shortly after the invention of photography (during the 1840s) and a great deal which are late Victorian. In less than one year over a thousand photographs were deposited in Norwich Library and by the mid- 1990s the collection had expanded to 30,000 prints and a similar number of negatives. The devastating Norwich library fire of 1994 destroyed around 15,000 Norwich prints, some of which were early images. Fortunately, many of the most important images were copied before the fire and those copies have since been purchased and returned to the library holdings. In 1999 a very successful public appeal was launched to replace parts of the lost archive and expand the collection. Today the collection (which was based upon the survey) contains a huge variety of material from amateur and informal work to commercial pictures. This includes newspaper reportage, portraiture, building and landscape surveys, tourism and advertising. There is work by the pioneers of photography in the region; there are collections by talented and dedicated amateurs as well as professional art photographers and early female practitioners such as Olive Edis, Viola Grimes and Edith Flowerdew. More recent images of Norfolk life are now beginning to filter in, such as a village survey of Ashwellthorpe by Richard Tilbrook from 1977, groups of Norwich punks and Norfolk fairs from the 1980s by Paul Harley and re-development images post 1990s. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

Norfolk .. [Kelly S

7 806 CAB NORFOLK .. [KELLY S CABINET MAKERS. Smith R. T. 8,67 Howard st.nth.Yarmth Duffield Jn. Mill la. Southtown,Yarmth See also {lpholsterers. Thompson Edwa,rd, Turner's court, St. Durrant James, Caister, Yarmouth .Alien Grice, Burnham market, Lynn Benedict's street, Norwich Dyball John William, h1gham, Stalham Hangay Richard, Museum court, St. TrenowathBroS.73.74&:noHigh st.Lynn Edwards Samuel, West Runton,Cromer Andrew's ;Broad street, Norwich Trevor, Page & Co. Exchange street; Enefer John, 19 Stanley street, Lynn Barber John, Watton S.O manufactory, St. Andrew's Broad Finch John, Mill la. Southtown, Yarmth Barrett William, so King st. Yarmouth street, Norwich French John W. 9 Apsleyrd. Yarmouth Baxter & Co. (wholesale & retail)~ 18 & Tuddenbarn R. & Sons, Burgh road, Hales Edwd. West Somerton, Yarmouth 22 Colegate street, Norwich Aylsham. See advertisement Hales Robt. West Somerton, Yarmouth· Brett Jonathan & Sons (wholesale & Vince Henry (wholesale), St. Julian's Hammond Wm.EastRudham,Swaffham retail), 26 St. Benedict's st. Norwich steam cabinet works, King ;;treet, Harvey Charles, Happisburgh, Stalharn Brett Henry, Market place, Fakenham Norwich. See advertisem~nt Hastings Edward, Austin street, Lynn Brumrnage J s. Bridewell st. Wymondhm Wilson Jonn. Rt. Muspole st. Norwich High Mrs. Charltte.Silfield, Wymondhm BunnFredk,.William,16Windsor rd.Lynn Woodrow Charles, Row 34, Yarmouth Hipper Thomas, 135 Philadelphia lane, Bussey Thos. 28 Upper King st. Norwich Yallop Chas. & Son, Broad st. Harleston New Catton, Norwich Butcher James, Hempton, Fakenham Hudson Thos. Swanton Abbot, Xorwich Carr Fredk. Daniel, Earles st. Thetford CAKE MANUFACTURERS. JohnsonHy.Wm.Cemeteryrd.Yarmouth Ghestney Elijah; Lion st. Holt R.S.O Far-Famed Cake Co. -

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List Of

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List of 1471412 It 44 Norfolk Census 1851 Index 6115160 Norfolk Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It 1 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1811-1825 375230 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1825-1839 375231 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1839-1859 375232 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1715-1734 1596461 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1734-1749 1596462 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1770-1774 1596563 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1774-1781 1596564 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1790-1797 1596566 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1798-1803 1596567 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1812-1819 1596597 Norfolk Marriages Parish Registers 1539-1812 496683 It 2 Norfolk Probate Inventories Index 1674-1825 1471414 It 17-20 Norfolk Tax Assessments 1692-1806 1471412 It 30-43 Norfolk Wills V.101 1854-1857 167184 Norfolk Alburgh Parish Register Extracts 1538-1715 894712 It 5 Norfolk Alby Parish Records 1600-1812 1526778 It 15 Norfolk Aldeby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 6 Norfolk Alethorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Arminghall Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Ashby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 7 Norfolk Ashby Parish Register Extracts 1646 894712 It 5 Norfolk Ashwell-Thorpe Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Aslacton Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Baconsthorpe Parish Register Extracts 1676-1770 894712 It 6 Norfolk Bagthorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Bale Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Bale Parish Register Extracts 1538-1716 894712 It 6 Norfolk Barmer Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barney Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barton-Bendish Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It -

The Stewards House, Binham

The Stewards House, Binham The Stewards House, Blacksmiths Yard, Binham, Norfolk, NR21 0AL North Norfolk Coast 2 miles, Norwich 20 miles Holt 7 miles A rare opportunity to acquire a Grade II listed traditional brick and flint house tucked away in a quiet location, just off the village centre. Having been tastefully re-furbished throughout, the property would make an excellent permanent or holiday home. Guide Price £450,000 The Property The property offered for sale is a Grade II listed traditional brick and flint house ACCOMMODATION under a pantile roof, delightfully situated in the heart of this popular North Norfolk village. The property enjoys a high degree of privacy being well set back from the The accommodation comprises - road. Having recently been fully refurbished to a very high standard whilst maintaining many of its original features, the property would make an ideal permanent or holiday home. The accommodation comprises an entrance hall, a Entrance Door double aspect sitting room with an open fireplace, a double aspect dining room Leading to:- and a handmade bespoke kitchen built and fitted by local craftsman Samphire Interiors, and a shower room. A first floor landing leads to three double bedrooms and a family bathroom. The double aspect features in many of the rooms make Entrance Hall the property light and airy. Outside there is a shingled parking area which in turn Oak flooring, radiator, coat pegs, staircase to the first floor. leads to a large detached garage, a particular feature of this property is the rear garden that is due south facing. The property is being sold with no upward chain. -

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 Socc Stakeholder Mailing List

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 SoCC Stakeholder Mailing List Applicant: Norfolk Vanguard Limited Document Reference: 5.1 Pursuant to APFP Regulation: 5(2)(q) Date: June 2018 Revision: Version 1 Author: BECG Photo: Kentish Flats Offshore Wind Farm This page is intentionally blank. Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Appendices Parish Councils Bacton and Edingthorpe Parish Council Witton and Ridlington Parish Council Brandiston Parish Council Guestwick Parish Council Little Witchingham Parish Council Marsham Parish Council Twyford Parish Council Lexham Parish Council Yaxham Parish Council Whinburgh and Westfield Parish Council Holme Hale Parish Council Bintree Parish Council North Tuddenham Parish Council Colkirk Parish Council Sporle with Palgrave Parish Council Shipdham Parish Council Bradenham Parish Council Paston Parish Council Worstead Parish Council Swanton Abbott Parish Council Alby with Thwaite Parish Council Skeyton Parish Council Melton Constable Parish Council Thurning Parish Council Pudding Norton Parish Council East Ruston Parish Council Hanworth Parish Council Briston Parish Council Kempstone Parish Council Brisley Parish Council Ingworth Parish Council Westwick Parish Council Stibbard Parish Council Themelthorpe Parish Council Burgh and Tuttington Parish Council Blickling Parish Council Oulton Parish Council Wood Dalling Parish Council Salle Parish Council Booton Parish Council Great Witchingham Parish Council Aylsham Town Council Heydon Parish Council Foulsham Parish Council Reepham -

Pick of the Churches

Pick of the Churches The East of England is famous for its superb collection of churches. They are one of the nation's great treasures. Introduction There are hundreds of churches in the region. Every village has one, some villages have two, and sometimes a lonely church in a field is the only indication that a village existed there at all. Many of these churches have foundations going right back to the dawn of Christianity, during the four centuries of Roman occupation from AD43. Each would claim to be the best - and indeed, all have one or many splendid and redeeming features, from ornate gilt encrusted screens to an ancient font. The history of England is accurately reflected in our churches - if only as a tantalising glimpse of the really creative years between the 1100's to the 1400's. From these years, come the four great features which are particularly associated with the region. - Round Towers - unique and distinctive, they evolved in the 11th C. due to the lack and supply of large local building stone. - Hammerbeam Roofs - wide, brave and ornate, and sometimes strewn with angels. Just lay on the floor and look up! - Flint Flushwork - beautiful patterns made by splitting flints to expose a hard, shiny surface, and then setting them in the wall. Often it is used to decorate towers, porches and parapets. - Seven Sacrament Fonts - ancient and splendid, with each panel illustrating in turn Baptism, Confirmation, Mass, Penance, Extreme Unction, Ordination and Matrimony. Bedfordshire Ampthill - tomb of Richard Nicholls (first governor of Long Island USA), including cannonball which killed him. -

Circular Walks East Norfolk Coast Introduction

National Trail 20 Circular Walks East Norfolk Coast Introduction The walks in this guide are designed to make the most of the please be mindful to keep dogs under control and leave gates as natural beauty and cultural heritage of the Norfolk coast. As you find them. companions to stretch one and two of the Norfolk Coast Path (part of the England Coast Path), they are a great way to delve Equipment deeper into this historically and naturally rich area. A wonderful Depending on the weather, some sections of these walks can array of landscapes and habitats await, many of which are be muddy. Even in dry weather, a good pair of walking boots or home to rare wildlife. The architectural landscape is expansive shoes is essential for the longer routes. Norfolk’s climate is drier too. Churches dominate, rarely beaten for height and grandeur than much of the country but unfortunately we can’t guarantee among the peaceful countryside of the coastal region, but sunshine, so packing a waterproof is always a good idea. If you there’s much more to discover. are lucky enough to have the weather on your side, don’t forget From one mile to nine there’s a walk for everyone here, whether sun cream and a hat. you’ve never walked in the countryside before or you’re a Other considerations seasoned rambler. Many of these routes lend themselves well to The walks described in these pages are well signposted on the trail running too. With the Cromer ridge providing the greatest ground, and detailed downloadable maps are available for elevation of anywhere in East Anglia, it’s a great way to get fit as each at www.norfolktrails.co.uk. -

North Norfolk District Council (Alby

DEFINITIVE STATEMENT OF PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY NORTH NORFOLK DISTRICT VOLUME I PARISH OF ALBY WITH THWAITE Footpath No. 1 (Middle Hill to Aldborough Mill). Starts from Middle Hill and runs north westwards to Aldborough Hill at parish boundary where it joins Footpath No. 12 of Aldborough. Footpath No. 2 (Alby Hill to All Saints' Church). Starts from Alby Hill and runs southwards to enter road opposite All Saints' Church. Footpath No. 3 (Dovehouse Lane to Footpath 13). Starts from Alby Hill and runs northwards, then turning eastwards, crosses Footpath No. 5 then again northwards, and continuing north-eastwards to field gate. Path continues from field gate in a south- easterly direction crossing the end Footpath No. 4 and U14440 continuing until it meets Footpath No.13 at TG 20567/34065. Footpath No. 4 (Park Farm to Sunday School). Starts from Park Farm and runs south westwards to Footpath No. 3 and U14440. Footpath No. 5 (Pack Lane). Starts from the C288 at TG 20237/33581 going in a northerly direction parallel and to the eastern boundary of the cemetery for a distance of approximately 11 metres to TG 20236/33589. Continuing in a westerly direction following the existing path for approximately 34 metres to TG 20201/33589 at the western boundary of the cemetery. Continuing in a generally northerly direction parallel to the western boundary of the cemetery for approximately 23 metres to the field boundary at TG 20206/33611. Continuing in a westerly direction parallel to and to the northern side of the field boundary for a distance of approximately 153 metres to exit onto the U440 road at TG 20054/33633. -

MELTON CONSTABLE NORTH Conservation Area NORFOLK DISTRICT COUNCIL Character Appraisal and Management Proposals

MELTON CONSTABLE NORTH Conservation Area NORFOLK DISTRICT COUNCIL Character Appraisal and Management Proposals Adopted - 19 June 2008 CONTENTS PART 1 CHARACTER APPRAISAL 1.0 Summary 1.1 Special Character 1.2 Key Characteristics 1.3 Key Issues 2.0 Introduction 2.1 Melton Constable Conservation Area 2.2 The Purpose of a Conservation Area Appraisal 2.3 Planning Policy Framework 2.4 Background to this study 3.0 Location & Landscape Setting 3.1 Location 3.2 Topography & Geology 3.3 Relation of the Conservation Area to the Surroundings 4.0 Historic Development & Archaeology 4.1 Historic Development 4.2 Archaeology 5.0 Spatial Analysis 5.1 Plan Form & Layout 5.2 Public realm 5.3 Shops 5.4 Landscape setting 5.5 Trees 6.0 Building Analysis 6.1 Building Types 6.2 Listed Buildings 6.3 Key Unlisted Buildings 6.4 Building Materials 7.0 Character Areas 7.1 The hamlet of Burgh Parva 7.2 Early railway housing making up the historic core of the village 7.3 Later phases of housing found mainly to the north of Briston Road 7.4 Industrial Estate PART 2 MANAGEMENT PROPOSALS 1.0 Summary of positive and negative features 2.0 Recommendations 3.0 Monitoring & review PART 1 1.3 Key Issues CHARACTER APPRAISAL A number of key issues have been identified relating to the character of the Conservation Area. These 1.0 SUMMARY form the basis for the Management Proposals in Part 2 of this document and are summarised below: 1.1 Special Character q Architectural Decay and Erosion Over the last thirty years there has been a In the context of North Norfolk, Melton Constable is a great deal of erosion of architectural unique village.