Trade Mark Inter Partes Decision (O/071/19)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Manufacturing Affiliates in Europe and Turkey

06-ORD 70H-002AA 7 Japanese Manufacturing Affiliates in Europe and Turkey - 2005 Survey - September 2006 Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) Preface The survey on “Japanese manufacturing affiliates in Europe and Turkey” has been conducted 22 times since the first survey in 1983*. The latest survey, carried out from January 2006 to February 2006 targeting 16 countries in Western Europe, 8 countries in Central and Eastern Europe, and Turkey, focused on business trends and future prospects in each country, procurement of materials, production, sales, and management problems, effects of EU environmental regulations, etc. The survey revealed that as of the end of 2005 there were a total of 1,008 Japanese manufacturing affiliates operating in the surveyed region --- 818 in Western Europe, 174 in Central and Eastern Europe, and 16 in Turkey. Of this total, 291 affiliates --- 284 in Western Europe, 6 in Central and Eastern Europe, and 1 in Turkey --- also operate R & D or design centers. Also, the number of Japanese affiliates who operate only R & D or design centers in the surveyed region (no manufacturing operations) totaled 129 affiliates --- 125 in Western Europe and 4 in Central and Eastern Europe. In this survey we put emphasis on the effects of EU environmental regulations on Japanese manufacturing affiliates. We would like to express our great appreciation to the affiliates concerned for their kind cooperation, which have enabled us over the years to constantly improve the survey and report on the results. We hope that the affiliates and those who are interested in business development in Europe and/or Turkey will find this report useful. -

BBE SOUND, INC. with That?" a Leading Audio Innovator's Diversification Is Helping to Build a Global, Cross-Market Brand

TOP GLOBAL MUSIC & AUDIO SUPPLIERS SALES RANKINGS ,> PERFORMANCE Q PROFILES es, lmtlate rentals, or check on an demand, Tri-Tech has also updated its every single cLlstomer who has come instrument's repair status directly package with an automated phone noti onboard," says Acton. "When someone through a website portal. fication system to alert customers when suggests a new feature, chances are Rycent developments have made it repairs are completed or special orders someone else could use it too. More possible for users to interface AIMsi have come in. The company is in the often than not we add that feature and it with eBay and Amazon, allowing the process of setting up touch-screen capa just makes our product that much more dealer to either send product and pricing bilities and an automated system to con attractive." ttl-low about information to the website or retrieve tact customers by text message. (800) 670-1736 information about products already list "Our software could not have become www.aimsi.biz ed on the site. In response to user what it is today without feedback from a~~E BBE SOUND, INC. with that?" A leading audio innovator's diversification is helping to build a global, cross-market brand. technology. Developed by inventor Bob Crooks, the technology addressed the phase and amplitude distortion inherent to loud speakers. Crooks' circuit automatically compensated for these problems, allow a o.~g '~"'" o •• \.)v •• ' 'a'" " 'a'"" . C. II .'"'. '"~o a ing speakers to more faithfully repro • ,. ," 'N aUT ·a· .\Q V duce amplified sound. "I went to hear a CHANNEL A 1()(,)r~IOUn I'llllf~~ DBEPROCESS til! t{J~l)rJrCJLJR PH()lI"~ CHANNELS POWER BBE's new D82 Sonic Maximizer plug-in for computer recording applications. -

DIRECTV® Universal Remote Control User's Guide

DirecTV-M2081A.qxd 12/22/2004 3:44 PM Page 1 ® DIRECTV® Universal Remote Control User’s Guide DirecTV-M2081A.qxd 12/22/2004 3:44 PM Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . .3 Features and Functions . .4 Key Charts . .4 Installing Batteries . .8 Controlling DIRECTV® Receiver. .9 Programming DIRECTV Remote . .9 Setup Codes for DIRECTV Receivers . .10 Setup Codes for DIRECTV HD Receivers . .10 Setup Codes for DIRECTV DVRs . .10 Programming to Control Your TV. .11 Programming the TV Input Key . .11 Deactivate the TV Input Select Key . .11 Programming Other Component Controls . .12 Manufacturer Codes . .13 Setup Codes for TVs . .13 Setup Codes for VCRs . .16 Setup Codes for DVD Players . .19 Setup Codes for Stereo Receivers . .20 Setup Codes for Stereo Amplifiers . .22 Searching For Your Code in AV1 or AV2 Mode . .23 Verifying The Codes . .23 Changing Volume Lock . .24 Restore Factory Default Settings . .25 Troubleshooting . .26 Repair or Replacement Policy . .27 Additional Information . .28 2 DirecTV-M2081A.qxd 12/22/2004 3:44 PM Page 3 INTRODUCTION Congratulations! You now have an exclusive DIRECTV® Universal Remote Control that will control four components, including a DIRECTV Receiver, TV, and two stereo or video components (e.g 2nd TV, DVD, or stereo). Moreover, its sophisticated technology allows you to consolidate the clutter of your original remote controls into one easy-to-use unit that's packed with features such as: z Four-position slide switch for easy component selection z Code library for popular video and stereo components z Code search to help program control of older or discon- tinued components z Memory protection to ensure you will not have to re- program the remote when the batteries are replaced Before using your DIRECTV Universal Remote Control, you may need to program it to operate with your particular com- ponent. -

UR5U-9000L and 9020L Cable Remote Control

th Introduction Button Functions A. Quick Set-Up Method C. Auto-Search Method E. AUX Function: Programming a 5 G. Programming Channel Control If your remote model has custom-program- 6 Quick Set-up Code Tables 7 Set-up Code Tables TV Operating Instructions For 1 4 STEP1 Turn on the device you want to program- Component mable Macro buttons available, they can be Manufacturer/Brand Set-Up Code Number STEP1 Turn on the Component you want to You can program the channel controls programmed to act as a 'Macro' or Favorite The PHAZR-5 UR5U-9000L & UR5U-9020L to program your TV, turn the TV on. TV CBL-CABLE Converters BRADFORD 043 program (TV, AUD, DVD or AUX). You can take advantage of the AUX func- (Channel Up, Channel Down, Last and Channel button in CABLE mode. This allows is designed to operate the CISCO / SA, STEP2 Point the remote at the TV and press tion to program a 5th Component such as a Numbers) from one Component to operate Quick Number Manufacturer/Brand Manufacturer/Brand Set-Up Code Number BROCKWOOD 116 STEP2 Press the [COMPONENT] button (TV, you to program up to five 2-digit channels, BROKSONIC 238 Pioneer, Pace Micro, Samsung and and hold TV key for 3 seconds. While second TV, AUD, DVD or Audio Component. in another Component mode. Default chan- 0 FUJITSU CISCO / SA 001 003 041 042 045 046 PHAZR-5 Holding the TV key, the TV LED will light AUD, DVD or AUX) to be programmed four 3-digit channels or three 4-digit channels BYDESIGN 031 032 Motorola digital set tops, Plus the majority th nel control settings on the remote control 1 SONY PIONEER 001 103 034 051 063 076 105 and [OK/SEL] button simultaneously STEP1 Turn on the 5 Component you want that can be accessed with one button press. -

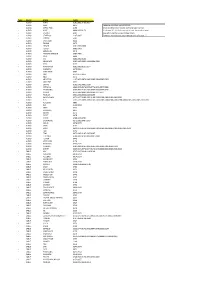

Company Vendor ID (Decimal Format) (AVL) Ditest Fahrzeugdiagnose Gmbh 4621 @Pos.Com 3765 0XF8 Limited 10737 1MORE INC

Vendor ID Company (Decimal Format) (AVL) DiTEST Fahrzeugdiagnose GmbH 4621 @pos.com 3765 0XF8 Limited 10737 1MORE INC. 12048 360fly, Inc. 11161 3C TEK CORP. 9397 3D Imaging & Simulations Corp. (3DISC) 11190 3D Systems Corporation 10632 3DRUDDER 11770 3eYamaichi Electronics Co., Ltd. 8709 3M Cogent, Inc. 7717 3M Scott 8463 3T B.V. 11721 4iiii Innovations Inc. 10009 4Links Limited 10728 4MOD Technology 10244 64seconds, Inc. 12215 77 Elektronika Kft. 11175 89 North, Inc. 12070 Shenzhen 8Bitdo Tech Co., Ltd. 11720 90meter Solutions, Inc. 12086 A‐FOUR TECH CO., LTD. 2522 A‐One Co., Ltd. 10116 A‐Tec Subsystem, Inc. 2164 A‐VEKT K.K. 11459 A. Eberle GmbH & Co. KG 6910 a.tron3d GmbH 9965 A&T Corporation 11849 Aaronia AG 12146 abatec group AG 10371 ABB India Limited 11250 ABILITY ENTERPRISE CO., LTD. 5145 Abionic SA 12412 AbleNet Inc. 8262 Ableton AG 10626 ABOV Semiconductor Co., Ltd. 6697 Absolute USA 10972 AcBel Polytech Inc. 12335 Access Network Technology Limited 10568 ACCUCOMM, INC. 10219 Accumetrics Associates, Inc. 10392 Accusys, Inc. 5055 Ace Karaoke Corp. 8799 ACELLA 8758 Acer, Inc. 1282 Aces Electronics Co., Ltd. 7347 Aclima Inc. 10273 ACON, Advanced‐Connectek, Inc. 1314 Acoustic Arc Technology Holding Limited 12353 ACR Braendli & Voegeli AG 11152 Acromag Inc. 9855 Acroname Inc. 9471 Action Industries (M) SDN BHD 11715 Action Star Technology Co., Ltd. 2101 Actions Microelectronics Co., Ltd. 7649 Actions Semiconductor Co., Ltd. 4310 Active Mind Technology 10505 Qorvo, Inc 11744 Activision 5168 Acute Technology Inc. 10876 Adam Tech 5437 Adapt‐IP Company 10990 Adaptertek Technology Co., Ltd. 11329 ADATA Technology Co., Ltd. -

Tuning Into a Radio Station

AM/FM Radio Receiving Function Tuning into a Radio Station Tuning into stations automatically 1. Press TUNER on the main unit several times to select either "AM" or "FM". 2. Press TUNING MODE so that the "AUTO" indicator on the display lights. 3. Press TUNING to start Auto tuning. Searching automatically stops when a station is found. When tuned into a radio station, the " TUNED " indicator on the display lights. If FM stereo broadcasting is tuned, the "FM STEREO" indicator lights. No sound is output while the " TUNED " indicator is off. When the signal from an FM radio station is weak: Radio wave may be weak depending on the building structure and environmental conditions. In that case, manually tune into the radio station of your choice by referring to the next section. Tuning into stations manually 1. Press TUNER on the main unit several times to select either "AM" or "FM". 2. Press TUNING MODE so that the "AUTO" indicator on the display goes off. 3. Press TUNING to select the desired radio station. The frequency changes by 1 step each time you press the button. The frequency changes continuously if the button is held down and stops when the button is released. Tune by looking at the display. To return the display to "AUTO": Press TUNING MODE on the main unit again. A station is automatically tuned. Normally "AUTO" should be displayed. Tuning into stations by frequency It allows you to directly enter the frequency of the radio station you want to listen to. 1. Press TUNER on the remote controller several times to select either "AM" or "FM". -

Aiwa UHD Android TV Product Catalogue 2020/2021

PRODUCT CATALOGUE 2020/2021 1 A new generation is here. New range, new products, new philosophy... But with the same feeling as always. Our products, designed with an exclusive Japanese engineering, offer a unique sound quality in the market. ANDROID TVs 4 ANDROID TVs LED556UHD TV UHD 55” ANDROID TV - TV UHD 55” (139 cm). - 4K Ultra High Definition Resolution (3840 x 2160). - Android 9.0 system. Google Assistant. - Built-in Chromecast. Built-in Wifi. - Dolby Audio System sound quality. - SURROUND sound system. - NICAM: Mono / Dual 1 / Dual 2 / Stereo. - Audio output power 8W + 8W. - Connections: LAN (RJ-45), Antenna, SAT, 3xHDMI, Cvbs, Digital Audio (Optical), Ci Slot, 2xUSB. - H.265 (HEVC) & DVB-T with CI/ DVB-T2 with CI+/ DVB-C/ DVB-S/S2. - Encoding: PAL / SECAM / NTSC. - Image format: Auto / 4:3 / 16:9 / Movie / Panorama. - OSD multilingual with 36 languages. - Subtitles. - Includes remote control with microphone, alkaline batteries, support and user manual. - Dimensions without stand: 122.67 x 9.24 x 71.62 cm. - Weight without stand: 10.5 kg. LED506UHD TV UHD 50” ANDROID TV - TV UHD 50” (127 cm). - 4K Ultra High Definition Resolution (3840 x 2160). - Android 9.0 system. Google Assistant. - Built-in Chromecast. Built-in Wifi. - Dolby Audio System sound quality. - SURROUND sound system. - NICAM: Mono / Dual 1 / Dual 2 / Stereo. - Audio output power 8W + 8W. - Connections: LAN (RJ-45), Antenna, SAT, 3xHDMI, Cvbs, Digital Audio (Optical), Ci Slot, 2xUSB. - H.265 (HEVC) & DVB-T with CI/ DVB-T2 with CI+/ DVB-C/ DVB-S/S2. - Encoding: PAL / SECAM / NTSC. - Image format: Auto / 4:3 / 16:9 / Movie / Panorama. -

Type Device Brand Codes

Type Device Brand Codes - AUDIO AIWA 0585,0885,0786,0687 - AUDIO APEX 0245 Codes for SRU2103 and SRU2103S - AUDIO APPLE iPOD 0190 Check whether your remote control is type S or not. - AUDIO BOSE 0868,0079,0179 If it is type "S", it is indicated on or near the product label, - AUDIO CARVER 0184 located inside the battery compartment. - AUDIO CENTRIOS 1107,0087 If there is no indication, your remote control is type "-". -

One" Peter Frampton

IN THIS ISSUE T 000817973 4401 9003TMAF9OXGZ Who Are The Top MONTY GREENLY AFT Nominees For This 3740 ELM Year's Grammys? LCNG BEACH CA 9 C 8C7 PAGE 6 DAT Comes On Strong At Winter CES I PAGE 4 Musicians May Strike January 20, 1990/$4.50 (U.S.),r $5.50 (CAN.), £3.50 (U.K.) THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT Over Label Funding PAGE 4 No Milli Vinyli; Studios Face New SeIIThru Reality 2nd Helpings Of Major Titles Fall Short Of Projections BY PAUL SWEETING diana Jones And The Last Crusade," The biggest disappointment ap- Top LPs Scarce "Lethal Weapon 2," and "Honey, I pears to be Warner Home Video's NEW YORK -The initial results Shrunk The Kids" could be as much "Lethal Weapon 2." When final or- . BY BRUCE HARING from three low- priced first -quarter ti- as 10 million units below what their ders close this week, according to and ED CHRISTMAN tles indicate that the studios may suppliers had projected. wholesaler sources, the studio will need to re-evaluate their expectations The three titles are being closely have prebooked approximately 2 mil - NEW YORK -For the first time, for the sell -through market beyond watched by the industry for indica- lion-2.5 million units -well below the the No. 1 album on Billboard's the holiday selling season. According tions of whether direct -to -sell- roughly 7.5 million Warner was re- Top Pop Albums chart is no longer to early estimates from distributors, through can be a viable strategy on a portedly seeking. -

Instruction Business Opportunities

NAKAMICHI YAMAHA DENON SONY HITACHI COMPACT DISCS! FREE CATALOG - Discover THE SOURCE. Our internation- COMPACT DISC PLAYERS Over 950 Listings -Same Day al buying group offers you a wide range SON' '(;1ES $1190 HITACHI DA.1000 $399 Shipping. Laury's Records SON`, , 'JO 1 ES 7T5 HITACHI DA -600 525 of quality audio gear at astonishing DIATONE DP 103 520 DENON DCD-2000 495 9800 North Milwaukee Avenue, prices! THE SOURCE newsletter con- DIATONE DP -101 825 KYUCERA DA -01 699 Des Plaines, IL 60016 YAMAHA CD.X1 465 AKAI CD -D1 575 tains industry news, new products. NAKAMICHI JAZZ COLLECTION OF 45 YEARS. L.P.'S. 78's. equipment reviews and a confidential CALL FOR PRICE AND AVAILABILITY TAPES. HAROLD LAMB, 225 NICHOLS RD., price list for our exclusive members. AIWA CASSETTE DECKS AKAI RECEIVERS SUWANEE. GEORGIA 30174" ADF-990 CALL AAR-1 CALL Choose from Aiwa, Alpine, Amber, ADF-770 CALL AAR-22 CALL RECORDS IN REVIEW original set. B&W, Denon, Grace. Harman Kardon, ADE-660 CALL AAR-32 CALL 1955-1981. Make offer. Charles Hunter. 216 Smoketree. ADF-330 CALL AAR-42 CALL Agoura, CA 91301." Kenwood, Mission, Nakamichi, Quad, VIDEO Revox, Rogers. Spica. Sumo. Walker. WE CARRY FULL LINE Of VIDEO EQUIPMENT LIVE OPERA PERFORMANCE ON DISCS Unbelievable Yamaha and much more. For more in- THIS MONTH'S SPECIALS ON BETA HI-FI Treasures --FREE Catalog LEGENDARY RECORDINGS SONY SL -2710 $899 SANYO 7200 5545 Box 104 Ansonia Station, NYC 10023' - formation call or write to: THE SOURCE. SONY SL -5200 565 TOSHIBA VA -36 675 SONY SL -2700 CALL SONY BETAMOVIE "SOUNDTRACKS. -

Save Code List for Future Reference Refer to the Setup Procedure Below and Look up the 3 Digit Code for Your Brand of TV, VCR, Etc., from the List Below

Save Code list for future reference Refer to the setup procedure below and look up the 3 digit code for your brand of TV, VCR, etc., from the list below. Refer to the Owner’s Manual for your remote for more information. Direct Code Entry Note, when all codes under a Brand Guarde esta lista de códigos para futura referencia. DAYTRON .......................... 0002 0502 KAYPANI ..................................... 0119 ORION ....................... 0713 0115 0105 SELECTRON ............ 1803 1603 1703 HDTV Set Top Boxes COLORTYME ............................... 0025 MARTA ........................................... 0126 RUNCO .......................................... 0534 CD have been searched the red indicator TV including LCD, DELL ......................... 0522 0404 0814 KEC ................................................ 0805 PANASONIC ............ 0718 0416 0007 SHARP.... 0509 0913 0907 0603 0002 COLT .............................................. 0237 MATSUSHITA ............................... 0830 SAMSUNG ....... 0037 0437 0625 0538 Refiérase al procedimiento de programación de abajo y 1. Press and hold the CODE SEARCH flashes rapidly for 3 seconds. Plasma, & Panel TVs DIAMOND VISION . 0622 0496 0810 KENWOOD ........................ 0002 0502 ........................... 0618 0807 0039 0739 ....... 0502 0224 0228 0202 0111 0813 GO VIDEO HDT100 .................... 0662 CRAIG .............. 0126 0037 0237 0426 MEDION ....................................... 0291 ................. 0147 0895 0997 0624 0335 ADC .............................................. -

DVD Player DV58AV KU EN.Book 2 ページ 2007年8月30日 木曜日 午後1時6分

DV58AV_KU_EN.book 1 ページ 2007年8月30日 木曜日 午後3時20分 Operating Instructions DVD Player DV58AV_KU_EN.book 2 ページ 2007年8月30日 木曜日 午後1時6分 Thank you for buying this Pioneer product. Please read through these operating instructions so you will know how to operate your model properly. After you have finished reading the instructions, put them away in a safe place for future reference. IMPORTANT CAUTION RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK DO NOT OPEN The lightning flash with arrowhead, within CAUTION: The exclamation point within an equilateral an equilateral triangle, is intended to alert TO PREVENT THE RISK OF ELECTRIC triangle is intended to alert the user to the the user to the presence of uninsulated SHOCK, DO NOT REMOVE COVER (OR presence of important operating and "dangerous voltage" within the product's BACK). NO USER-SERVICEABLE PARTS maintenance (servicing) instructions in the enclosure that may be of sufficient INSIDE. REFER SERVICING TO QUALIFIED literature accompanying the appliance. magnitude to constitute a risk of electric SERVICE PERSONNEL. shock to persons. D1-4-2-3_En IMPORTANT NOTICE – THE SERIAL NUMBER FOR THIS EQUIPMENT IS LOCATED IN THE REAR. PLEASE WRITE THIS SERIAL NUMBER ON YOUR ENCLOSED WARRANTY CARD AND KEEP IN A SECURE AREA. THIS IS FOR YOUR SECURITY. D1-4-2-6-1_En NOTE: This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class B digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference in a residential installation. This equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the instructions, may cause harmful interference to radio communications.