Equity and Excellence in Australian Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jump on Board High-Performing Not-For-Profit Boards in Fundraising

JUMP ON BOARD HIGH-PERFORMING NOT-FOR-PROFIT BOARDS IN FUNDRAISING November 2019 PREPARED BY Melissa Smith Director & Founder, Noble Ambition in partnership with Perpetual ABOUT THE AUTHOR Melissa is former Global Fundraiser of the Year (IFC, 2011) and Australian Fundraiser of the Year (FIA, 2011). She has facilitated philanthropic giving across education, the arts and health, and worked with hundreds of donors in Australia, Asia and the United States. Melissa has led four fundraising programs from start-up to established, from Powerhouse Museum and Sydney Opera House in the arts, to University of Technology, Sydney and RMIT University, in education. Melissa has a BA Hons (First Class, USyd), Masters of Management (UTS); is a Churchill Fellow (2007) and a graduate of University of Melbourne’s Asialink Leaders Program and Benevolent Society’s Sydney Leadership Program. She has presented her research internationally in areas including the impact of culture on philanthropy, international best practice in arts philanthropy, and the role of leadership in philanthropy. Melissa’s lifelong interest and experience enables her to understand both philanthropy and fundraising. As a thought leader in the philanthropic and fundraising sector, she is in the privileged position of possessing the practical and strategic skills to support both pillars equally. Jump on Board: High-performing not-for-profit boards in fundraising 2 Philanthropic fundraising in Australia is in a state of rapid change. While mass giving is in decline, major gifts are on the rise, and in coming years we will see the largest intergenerational transfer of wealth in our nation’s history. This undoubtedly presents an exciting opportunity for the non-for-profit (NFP) sector to attract significant support, but also raises questions about how prepared NFPs are to maximise this opportunity. -

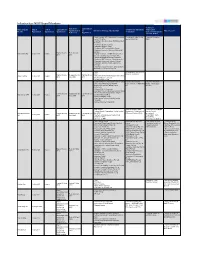

Female Participation on Boards of ASX200 Alphabetic by Company

Female participation on boards of ASX200 Alphabetic by company ASX Code Company Chair State Industry Group Name 2009 2009 2009 % total female female directors directors Totals 1,474 128 8.7 ABP Abacus Property Group Mr John Thame NSW Real Estate 7 0 0.0 ABC Adelaide Brighton Limited Mr MA Kinnaird SA Materials 6 0 0.0 AGK AGL Energy Limited Mr Mark Johnson NSW Utilities 9 1 11.1 AJL AJ Lucas Group Ltd Mr Allan S Campbell NSW Capital Goods 5 0 0.0 ALS Alesco Corporation Limited Mr Sean Wareing NSW Capital Goods 8 0 0.0 AWC Alumina Limited Mr Donald Morley VIC Materials 6 1 16.7 AMC Amcor Limited Mr Chris Roberts VIC Materials 8 1 12.5 AMP AMP Limited Mr Peter Mason NSW Insurance 8 1 12.5 ANN Ansell Limited Mr Peter Barnes VIC Health Care Equipment & Services 7 1 14.3 APA APA Group Mr Leonard Bleasel NSW Utilities 7 0 0.0 APN APN News & Media Limited Mr Gavin O'Reilly NSW Media 10 0 0.0 AQP Aquarius Platinum Limited Mr Nicholas Sibley WA Materials 8 0 0.0 AQA Aquila Resources Mr Anthony Poli WA Energy 4 0 0.0 ALL Aristocrat Leisure Limited Mr David Simpson NSW Consumer Services 7 3 42.9 AOE Arrow Energy Limited Mr John Reynolds QLD Energy 7 0 0.0 AIO Asciano Group Mr Malcolm Broomhead VIC Transportation 6 0 0.0 AJA Astro Japan Property Trust Mr Allan McDonald NSW Real Estate 3 1 33.3 ASX ASX Limited Mr Maurice Newman NSW Diversified Financials 8 1 12.5 AGO Atlas Iron Limited Mr Geoff Clifford WA Materials 4 0 0.0 AAX Ausenco Limited Mr Wayne Goss QLD Capital Goods 6 0 0.0 AUN Austar United Communications Limited Mr Mike Fries NSW Media 7 0 0.0 ALZ Australand Property Group Mr Lui Chee NSW Real Estate 8 0 0.0 ANZ Australia And New Zealand Banking Group Limited Mr Charles Goode VIC Banks 10 1 10.0 AAC Australian Agricultural Company Limited. -

Adara Partners Is a Corporate Advisory Firm with a Difference Adara Partners Showcasing the Power of Financial Services to Effect Social Change

ADARA PARTNERS IS A CORPORATE ADVISORY FIRM WITH A DIFFERENCE ADARA PARTNERS SHOWCASING THE POWER OF FINANCIAL SERVICES TO EFFECT SOCIAL CHANGE UNIQUE BUSINESS-FOR-PURPOSE Adara Panel Members undertake this role separately from their other professional MODEL and home firm commitments, which Adara Partners is a top-tier corporate advisory remain unchanged. firm, providing independent financial and strategic advice and complex commercial Our Panel Members provide advice focused on problem solving services to leading Australian areas where independence is critical. Thus companies, governments and families. providing advice on key strategic matters, second opinion on mergers and acquisitions, capital management advice and complex Our sole purpose is to deliver financial commercial problem solving services are key services expertise at the highest levels areas of focus. to our clients, with fees generated on transactions going to directly benefit Adara Partners builds on 19 years of successful people LIVING in extreme poverty. work done by the Adara Group, which is internationally recognised as one of the earliest examples of a business-for-purpose Our purpose-driven model is unique in the and a completely embedded private-sector global financial services industry. The Adara and non-profit partnership. Panel Member structure brings together some of Australia’s most senior leaders in financial Adara Partners represents innovative and services. As Adara Panel Members, they provide important leadership in the global financial wise counsel and senior advice to our clients, services industry. with their time, effort and expertise donated to Adara Partners. This allows for maximum generation of profits to support people living in poverty in the developing world. -

How Does Sustainable Banking Add Up?

HOW DOES SUSTAINABLE BANKING ADD UP? A CATALYST REPORT HOW DOES SUSTAINABLE BANKING ADD UP. A CATALYST REPORT 1 ABOUT CATALYST Catalyst is a not for profit policy network established in 2007. We work closely with trade unions, non-Government organisations and academics to promote social and economic equality and improved standards of corporate social responsibility. Our founding principle is to produce work that promotes good lives, good work and good communities. In October 2014 Catalyst formally merged with The Australia Institute and now operates as an independent branch AUTHOR Martijn Boersma July 2015 Catalyst Australia Incorporated Level 3, 4 Goulburn Street, Sydney Tel: +61 (0) 2 8268 9718 www.catalyst.org.au @CatalystAus HOW DOES SUSTAINABLE BANKING ADD UP. A CATALYST REPORT 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 04 The Australian Banking Sector 05 Responsibilities 06 Supervision 06 Challenges 07 Performance 08 2. Voluntary Disclosures 09 Reporting 09 Guidance 09 Environmental Transparency 10 Social Transparency 10 Summary 11 3. Responsible Finance 12 Products and Services 12 Risk Management and Sector Screening 12 Sustainability Indices 14 Summary 14 4. Stakeholder Engagement 15 Internal Stakeholders 15 External Stakeholders 16 Multistakeholder Initiatives 17 Summary 17 5. Corporate Governance 18 Business Ethics 18 Remuneration 19 Summary 20 6. Discussion 21 Findings 22 Bridging the Governance Gap 23 Extended Supervision 24 7. Conclusion and Recommendations 25 Appendix 29 Glossary 31 Disclaimer: Disclaimer: Catalyst Catalyst Australia Australia has made every has effort made to produce every and effort analyse informationto produce and dataand with analyse the greatest information possible care. But and any guaranteedata with or liability the for its greatestcorrectness, completenesspossible and/orcare. -

Annual Repo Rt

ANNUAL REPORT The University of New South Wales – Volume One 1 Volume © UNSW Published by the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Resources) The University of New South Wales UNSW Sydney NSW 2052 Australia Telephone: +61 2 9385 1000 Facsimilie: +61 2 9385 2000 Website: www.unsw.edu.au Operating Hours UNSW operates under standard business hours. As many departments operate beyond these hours, please contact the relevant area to confirm availability. Production Team Compilation Cecilia White Editing Blanche Hampton Proofing Dina Christofis, Ben Allen Review Panel Cecilia White, Judith Davoren, Morgan Stewart, Lyndell Carter, Elisabeth Nyssen, Helena Brusic Design Helena Brusic, UNSW Publishing & Printing Services Photography Karen Mork, Helena Brusic, www.photospin.com Printing Pegasus Printing ISSN 0726-8459 Volume 1 2005 The University Of New South Wales - Volume One - Volume The University Of New South Wales ANNUAL REPORT ‘It is the passion and commitment of the UNSW community that will ensure we continue to make such a valuable contribution to the wider community, our country and our region’ Professor Mark Wainwright, AM Vice-Chancellor and President Governance Community 23 113 Overview 2005 in Review 7 35 2005 The University Of New South Wales - Volume One - Volume The University Of New South Wales ANNUAL PART 1: Overview ............................... 7 PART 2: REPORT Governance ......................... 23 PART 3: 2005 in Review .................... 35 PART 4: Community ........................... 113 THE UNIVERSITY AND ITS graduates THE FUNCTIONS OF THE • To contribute to the development, the well-being and stability of our region of South-East Asia through UNIVERSITY scholarship, collaboration, consultation, training and exchange. The functions of the University (within the limits of its resources) include: • To enable all our students to have an outstanding learning experience and to reach their full potential. -

STC Annualreport 2015 Bigger.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT BETRAYAL CANNIBALISM COURAGE EYE WITNESS FAMILY TIES FEMINISM FRENEMIES HILARITY LONGING LOVE AND ATTRACTION MADNESS MORTALITY POLITICS RECKONING SINGING TRANSITION TRAVEL Aims of the Company To provide first class theatrical entertainment for the people of Sydney – theatre that is grand, vulgar, intelligent, challenging and fun. That entertainment should reflect the society in which we live thus providing a point of focus, a frame of reference, by which we come to understand our place in the world as individuals, as a community and as a nation. Richard Wherrett, 1980 Founding Artistic Director Marshall Napier, Richard Roxburgh, Eamon Farren, Cate Blanchett and Martin Jacobs in The Present. Photo: Lisa Tomasetti 2015 in Numbers ACTORS 146% AND CREATIVES 2 889 255 EMPLOYED 131 $418,855 C R 19TEACHING OF TI KET P ICE 318,899 SAVINGS PASSED ON TO ARTISTS TIX 759 6,330 SUNCORP TWENTIES CUSTOMERS EMPLOYED TIX PAID PEOPLE OVERSEAS 10,045 SAW A AND ATTENDEES WAITING FOR GODOT N TIONAL OVER $20M TO STC’S 2015 PROGRAM INTERNATIONAL TOTAL TICKET 47.7% PERFORMANCES INCOME EARNED REDUCTION IN WORLD GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS SINCE 2007 PREMIERES 1,273 4 71.3% WEEKS AVERAGE OF WORK 20,513 5,887 PLAYWRIGHTS REDUCTION CAPACITY TOTAL SUBSCRIBERS NEW SUBSCRIBERS 15 ON COMMISSION IN WATER USAGE SINCE 2007 86% FOR ACTORS 4 5 Ian Jonathan Narev Church CHAIR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR During Board discussions at Sydney Theatre Company, we refer Mark Leonard Winter, Jacek Koman, Geoffrey Rush and Robyn Nevin I am delighted and honoured to be the next Artistic Director of Paula Arundell (background), Eryn Jean Norvill and Paula Arundell regularly to Richard Wherrett’s founding aims of the Company: in King Lear. -

ANZ 2020 Annual Report

9 November 2020 Market Announcements Office ASX Limited Level 4 20 Bridge Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 ANZ 2020 Annual Report Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) today released its 2020 Annual Report. It has been approved for distribution by ANZ’s Board of Directors. Yours faithfully Simon Pordage Company Secretary Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited For personal use only Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 ANZ Centre Melbourne, Level 9A, 833 Collins Street, Docklands VIC 3008 For personal use only 2020 ANNUAL REPORT Overview How we Performance Remuneration Directors’ Financial Shareholder create value overview report report report information CUSTOMER STORY ADAPTING Growing business An ANZ customer for more than 50 years, fellahamilton has been during a crisis in the business of Australian women’s fashion since the early 1970s. Today, the company is managed by David Hamilton (son of the eponymous founder) and his wife, Sharon Hamilton, CEO. When the COVID-19 pandemic first hit Australia in March, times were challenging. Within the first few weeks of lockdowns, dentists and hospitals. We’ve hired back they had to let go of employees at their all of our staff and have never been busier,” Moorabbin factory and retail stores says Sharon. nationally were shut. David credits the move into making PPE However, shortly after, a doctor friend of to his wife’s optimistic nature and tendency Sharon’s asked her to make a scrub set, as to ‘think outside the box’. there was a limited supply of Personal “Changing direction wasn’t easy,” says David. -

Pax World Proxy Voting from July 1, 2017 Thru June 30, 2018

<DOCUMENT> <TYPE>N-PX <SEQUENCE>1 <FILENAME>paxtrustiii063018.txt <DESCRIPTION>PAX WORLD SERIES TRUST III FORM N-PX <TEXT> SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-PX REPORT ANNUAL REPORT OF PROXY VOTING RECORD OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number 0001598735 PAX WORLD FUNDS SERIES TRUST III (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 30 Penhallow St, Ste. 400 Portsmouth, NH 03801 (Address of principal executive offices) Registrants Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (800) 767-1729 Pax Ellevate Management LLC 30 Penhallow Street, Suite 400 Portsmouth, NH 03801 Attn: Joseph F. Keefe (Name and address of agent for service) Date of fiscal year end: December 31, 2018 Date of reporting period: July 1, 2017 - June 30, 2018 Item 1: Proxy Voting Record Fund Name : Pax Ellevate Global Womens Leadership Fund 07/01/2017 - 06/30/2018 ________________________________________________________________________________ Abbott Laboratories Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP 002824100 04/27/2018 Voted Meeting Type Country of Trade Annual United States Issue No. Description Proponent Mgmt Rec Vote Cast For/Against Mgmt 1.1 Elect Robert J. Alpern Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.2 Elect Roxanne S. Austin Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.3 Elect Sally E. Blount Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.4 Elect Edward M. Liddy Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.5 Elect Nancy McKinstry Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.6 Elect Phebe N. Mgmt For Withhold Against Novakovic 1.7 Elect William A. Osborn Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.8 Elect Samuel C. Scott Mgmt For Withhold Against III 1.9 Elect Daniel J. -

Infrastructure NSW Board Members

Infrastructure NSW Board Members Positions in Date of Re- Expiry Date of Name of Board Date of Term of Expiry Date of Positions and Interests in Professional/ Appointment or Re- Board and Committee Memberships Other interests Member Appointment Appointment Appointment Corporations Business Associations Retirement Appointment and Trade Unions • Panel member, GST Distribution Committee • Consultant, Trility Pty Ltd • Board of Governors, (ended 7/11/2012) (ended 30/6/2012) CEDA • Chairman, Blue Star Group Holdings (ended 16/1/2013) • Chairman, Bradken Limited • Chairman, Nuance Group • Chairman, QBE Australia/Asia-Pacific • Chairman, Council of Advisors, Rothschild Australia Expired 30 June Retired 3 July Nick Greiner AC 15 July 2011 4 years • Deputy Chairman, CHAMP Group Services 2015 2013 • Director and Chairman, Accolade Wine • Director Australian Stationery Industries • Chairman, QBE Insurance Group Australia • Chairman, Degremont Advisory Council • Chairman, Advisory Board, Opportunity Cambodia • Chairman, Playup Interactive Entertainment (Australia) Pty Ltd (REVO Pty Ltd) • AMIC • Managing Director, Fletcher • AWI Group of Companies Expired 30 June Reappointed 30 Expiring 30 June Roger Fletcher 15 July 2011 4 years • National and NSW State Export Lamb, Sheep 2015 June 2015 2019 and Goat Industries Council • CS Agriculture Pty Ltd • COAG Reform Council Expert Panel on Cities • Director and member, • Member, Australian • University of Wollongong SMART Pearse Nominees (NSW) Pty Institute of Company Infrastructure Advisory Board (ended -

Review of Funding for Schooling

Review of Funding for Schooling Final Report | December 2011 Review of Funding for Schooling Final Report December 2011 Expert panel David Gonski AC, Chair Ken Boston AO Kathryn Greiner AO Carmen Lawrence Bill Scales AO Peter Tannock AM ISBN 978-0-642-78222-9 [PRINT] ISBN 978-0-642-78223-6 [PDF] ISBN 978-0-642-78224-3 [RTF] With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, the Department’s logo, any material protected by a trade mark and where otherwise noted all material presented in this document is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/) licence. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website (accessible using the links provided) as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode). The document must be attributed as the Review of Funding for Schooling—Final Report. Disclaimer: The material contained in this report has been developed by the Review of Funding for Schooling. The views and opinions expressed in the materials do not necessarily reflect the views of or have the endorsement of the Australian Government or of any Minister, or indicate the Australian Government’s commitment to a particular course of action. The Australian Government and the Review of the Funding for Schooling accept no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents and accept no liability in respect of the material contained in the report. For enquiries please contact: Review of Funding for Schooling Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations GPO Box 9880 CANBERRA CITY ACT 2601 The report can be accessed via the DEEWR website at: www.schoolfunding.gov.au Contents Acronyms and abbreviations .................................................................................................. -

Final VET Sector Report

IN THE SAME SENTENCE Bringing higher and vocational education together David Gonski AC and Peter Shergold AC MARCH 2021 Publication date March 2021 Contact for enquiries [email protected] Contents Introduction 3 1. A new tertiary institution 9 2. Careers guidance for all 17 3. Making vocational education and training attractive and accessible to secondary school students 23 4. Improve the level and quality of engagement with industry 31 5. Income -contingent loans for VET 37 Conclusion 40 Endnotes 41 APPENDIX A: Terms of Reference 43 APPENDIX B: Stakeholder consultation 45 APPENDIX C: Abbreviations and acronyms 47 APPENDIX D: Supporting evidence 48 APPENDIX E: Bibliography 56 In the same sentence: Bringing higher and vocational education together 1 Introduction Earlier this year the NSW Government asked us to examine vocational education and training (VET) in NSW. We were asked to provide advice on how the state’s VET system could best address ongoing and emerging skills shortages, paying particular regard to its quality, efciency and structural complexity. It was indicated that we should consider how to integrate secondary, vocational and higher education learning opportunities, how to re-imagine industry engagement and how to improve career advice to support lifelong learning. It was also suggested that we should seek to understand any negative public perceptions of VET. The request refects the NSW Government view considering the context of COVID-19, which that an efective and sustainable VET sector is presents a pressing need for a VET sector crucial for providing the skilled workforce needed equipped to support a strong NSW economy. -

10 September 2008 the Manager Company Announcements Office ASX Limited Level 4, Exchange Centre 20 Bridge Street SYDNEY NSW 20

Westfield Management Limited 10 September 2008 Level 24, Westfield Towers 100 William Street Sydney NSW 2011 The Manager GPO Box 4004 Company Announcements Office Sydney NSW 2001 ASX Limited Australia Level 4, Exchange Centre Telephone 02 9358 7000 20 Bridge Street Facsimile 02 9358 7077 Internet westfield.com SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Sir/Madam CARINDALE PROPERTY TRUST (ASX: CDP) 2008 ANNUAL REPORT Attached is the Annual Report for Carindale Property Trust for the year ended 30 June 2008. The Annual Report will be despatched to members in the week commencing 15 September 2008. The Report can be accessed on the Trust’s website at www.carindalepropertytrust.com.au Yours faithfully WESTFIELD MANAGEMENT LMIMTED Responsible Entity of Carindale Property Trust Simon Tuxen Company Secretary Encl. Westfield Management Limited ABN 41 001 670 579 AFS Licence 230329 as responsible entity for Carindale Property Trust ABN 29 192 934 520 ARSN 093 261 744 Carindale Property Trust 2008 Annual Report Westfi eld Management Limited ABN 41 001 670 579 AFS Licence 230329 as responsible entity of Carindale Property Trust ARSN 093 261 744 www.carindalepropertytrust.com.au Directory Carindale Property Trust Carindale Property Trust ABN 29 192 934 520 Carindale Property Trust was listed on the Australian ARSN 093 261 744 Stock Exchange in 1996. The Trust’s sole investment Responsible Entity Westfi eld Management Limited is a 50% interest in Westfi eld Carindale, one of ABN 41 001 670 579 AFS Licence 230329 Brisbane’s largest regional shopping centres Registered Offi ce Level 24, Westfi eld Towers at 116,767 square metres.