Aurora (Astronomy)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Severe Space Weather

Severe Space Weather ThePerfect Solar Superstorm Solar storms in +,-. wreaked havoc on telegraph networks worldwide and produced auroras nearly to the equator. What would a recurrence do to our modern technological world? Daniel N. Baker & James L. Green SOHO / ESA / NASA / LASCO 28 February 2011 !"# $ %&'&!()*& SStormtorm llayoutayout FFeb.inddeb.indd 2288 111/30/101/30/10 88:09:37:09:37 AAMM DRAMATIC AURORAL DISPLAYS were seen over nearly the entire world on the night of August !"–!&, $"%&. In New York City, thousands watched “the heavens . arrayed in a drapery more gorgeous than they have been for years.” The aurora witnessed that Sunday night, The New York Times told its readers, “will be referred to hereafter among the events which occur but once or twice in a lifetime.” An even more spectacular aurora occurred on Septem- ber !, $"%&, and displays of remarkable brilliance, color, and duration continued around the world until Septem- ber #th. Auroras were seen nearly to the equator. Even after daybreak, when the auroras were no longer visible, disturbances in Earth’s magnetic fi eld were so powerful ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY / © PHOTO RESEARCHERS that magnetometer traces were driven off scale. Telegraph PRELUDE TO THE STORM British amateur astronomer Rich- networks around the globe experienced major disrup- ard Carrington sketched this enormous sunspot group on Sep- tions and outages, with some telegraphs being completely tember $, $()*. During his observations he witnessed two brilliant unusable for nearly " hours. In several regions, operators beads of light fl are up over the sunspots, and then disappear, in disconnected their systems from the batteries and sent a matter of ) minutes. -

Wiki Template-1Eb7p59

Wikipedia Reader https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aurora Selected by Julie Madsen - Entry 10 1 Aurora From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia An aurora, sometimes referred to as a polar lights or north- ern lights, is a natural light display in the sky, predominantly seen in the high latitude (Arctic and Antarctic) regions.[1] Au- roras are produced when the magnetosphere is sufficiently disturbed by the solar wind that the trajectories of charged particles in both solar wind and magnetospheric plasma, mainly in the form of electrons and protons, precipitate them into the upper atmosphere (ther- mosphere/exosphere), where their energy is lost. The resulting ion- ization and excitation of atmospheric constituents emits light of varying color and complexity. The form of the aurora, occur- ring within bands around both polar regions, is also dependent on the amount of acceleration imparted to the precipitating parti- cles. Precipitating protons generally produce optical emissions as incident hydrogen atoms after gaining electrons from the atmosphere. Proton Images of auroras from around the world, auroras are usually observed at including those with rarer red and blue lower latitudes.[2] lights Wikipedia Reader 2 May 1 2017 Contents 1 Occurrence of terrestrial auroras 1.1 Images 1.2 Visual forms and colors 1.3 Other auroral radiation 1.4 Aurora noise 2 Causes of auroras 2.1 Auroral particles 2.2 Auroras and the atmosphere 2.3 Auroras and the ionosphere 3 Interaction of the solar wind with Earth 3.1 Magnetosphere 4 Auroral particle acceleration 5 Auroral events of historical significance 6 Historical theories, superstition and mythology 7 Non-terrestrial auroras 8 See also 9 Notes 10 References 11 Further reading 12 External links Occurrence of terrestrial auroras Most auroras occur in a band known as the auroral zone,[3] which is typically 3° to 6° wide in latitude and between 10° and 20° from the geomagnetic poles at all local times (or longitudes), most clearly seen at night against a dark sky. -

GEOMAGNETISM -A HISTORICAL REVIEW Sashikanth Rapeti

GEOMAGNETISM -A HISTORICAL REVIEW Sashikanth Rapeti To cite this version: Sashikanth Rapeti. GEOMAGNETISM -A HISTORICAL REVIEW. 2020. hal-02901860 HAL Id: hal-02901860 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02901860 Preprint submitted on 17 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. GEOMAGNETISM – A HISTORICAL REVIEW R. Sashikanth Assistant Professor and Head of the Department Department of Physics and Space Sciences Gandhi Institute of Technology and Management, Gangapada, Bhubhaneshwar, Odisha, India. E-mail : [email protected], [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Abstract : This specific paper addresses the historical events that had led in the current scenario, to the development of one of the most important fundamental research areas – Geomagnetism, which might even date back to probably millions of years embedded in the core scientific aspects of even ancient civilizations. The solar wind and its associated magnetic field have their source in the Sun and their interaction with the geo-magnetic field which extends into outer space has its origin inside the earth’s core. Needless to say, the contributions of many scientific researchers on the dynamics of upper, middle and lower atmospheres of the earth is really outstanding and remarkable, but certain important aspects appear to have been missed. -

Olmsted 200 Bicentennial Notes About Olmsted Falls and Olmsted Township – First Farmed in 1814 and Settled in 1815 Issue 42 November 1, 2016

Olmsted 200 Bicentennial Notes about Olmsted Falls and Olmsted Township – First Farmed in 1814 and Settled in 1815 Issue 42 November 1, 2016 Contents November Meteors Have Connection to Olmsted History 1 Sesquicentennial Coin Turns Up 7 Did Peltzes Move to California for Their Health? 8 Chestnut Grove Will Host Veterans Day Ceremony 10 Still to Come 11 November Meteors Have Connection to Olmsted History If the nighttime sky is dark enough and clear enough around the middle of November and you happen to see one or more meteors – or “shooting stars” – you might be witness to a portion of one of the best-known annual meteor showers. But maybe you didn’t know – until now – about that meteor shower’s connection to the family for whom Olmsted Falls and Olmsted Township, as well as North Olmsted, are named. Meteor showers occur when the Earth, in its orbit around the sun, encounters streams of particles. Those particles are left in the wake of comets in their trips from the edges of the solar system to close passes by the sun and then back to the outer realms. The Earth experiences several meteor showers of varied intensity each year. One of the best- known meteor showers is the Perseids, partly because they reliably provide an average of about one meteor each minute at their peak. It’s also partly because they occur in mid-August, when the weather is warm enough that it is comfortable for observers to stay outside for long periods NASA released this photo of the Leonids as in the middle of the night. -

Between Two Empires: the Toronto Magnetic Observatory and American Science Before Confederation"

Article "Between Two Empires: the Toronto Magnetic Observatory and American Science before Confederation" Gregory Good Scientia Canadensis: Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine / Scientia Canadensis : revue canadienne d'histoire des sciences, des techniques et de la médecine , vol. 10, n° 1, (30) 1986, p. 34-52. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/800224ar DOI: 10.7202/800224ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 14 février 2017 07:54 34 BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE TORONTO MAGNETIC OBSERVATORY AND AMERICAN SCIENCE BEFORE CONFEDERATION* Gregory Good** (Received 20 November 1985. Revised/Accepted 19 May 1986) PERSPECTIVES ON THE TORONTO MAGNETIC OBSERVATORY The Magnetic Observatory was founded at Toronto in 1839 as part of the worldwide magnetic Crusade of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the Royal Society of London.1 Although it was a focus of scientific research and of institutional development in Canada for decades, little attention has been given to it. -

Denison Olmsted (1791-1859), Scientist, Teacher, Christian: a Biographical Study of the Connection Of

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Gary Lee Schoepflin for the degree ofDoctor of Philosophy in General Science presented on June 17, 1977 Title:DENISON OLMSTED (1791-1859), SCIENTIST, TEACHER, CHRISTIAN: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF THE CONNECTION OF SCIENCE WITH RELIGION IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: Danie JJ one s A biographical study of Denison Olmsted, focusing upon his own Christian world view and its connection with his various activities in science, supports the view that religion served as a significant factor in the promotion of science in America during this time period. Olmsted taught physics, meteorology and astronomy at Yale from 1826 to 1859, and from this position of influence, helped mold the minds and outlook of a new generation of scientists, of hundreds of students who came to Yale to obtain a liberal educa- tion, and of those members of society who attended his popular lectures.Olmsted's personal perspective was that science was God-ordained, that it would ever harmonize with religion, that it was indeed a means of hastening the glorious millennium. Olmsted lived in an era characterized by an unprecedented revivalism and emphasis upon evangelical Christianity. He graduated from Yale (1813) at a time when its president, Reverend Dr. Timothy Dwight, one of the most influential clergymen in New England, was at the height of his fame. Olmsted subsequently studied theology under Dwight, but before completing his prepara- tion for the ministry, Olmsted was appointed to a professorship of science at the University of North Carolina where he taught from 1818 until he was called to Yale in 1826. -

George P. Merrill Collection, Circa 1800-1930 and Undated

George P. Merrill Collection, circa 1800-1930 and undated Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: PHOTOGRAPHS, CORRESPONDENCE AND RELATED MATERIAL CONCERNING INDIVIDUAL GEOLOGISTS AND SCIENTISTS, CIRCA 1800-1920................................................................................................................. 4 Series 2: PHOTOGRAPHS OF GROUPS OF GEOLOGISTS, SCIENTISTS AND SMITHSONIAN STAFF, CIRCA 1860-1930........................................................... 30 Series 3: PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL SURVEY OF THE TERRITORIES (HAYDEN SURVEYS), CIRCA 1871-1877.............................................................................................................. -

On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances

: TRANSACTIONS CONNECTICUT ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES. VOX^XJJVIE III t7> NEW H AYEN PUBLISHED BY THE ACADEMY, 1874 to 1878. TulUr, Murehouse 4 Taylor, Printers, New Ha ———— CONTENTS. PAGE List of Additions to the Library,..,. v Art. I. —Report on the dredgings in the region of St. George's Banks, in 1872. By S. I. Smith and O. Harger. Plates 1 -8, 1 Art. IL—Descriptions op new and rare species of Hy- DROIDS from the NeW EnGLAND COAST. By S. F, Clark. Plates 9-10, 58 Art. III. On the Chondrodite from the Tilly-Foster IRON mine, Brewster, N. Y, By E. S. Dana, Plates 11-13, 67 Art. IV. On the Transcendental curves sin y sin iny=. a sin ic sin ??a; -|- ^''- By II. A. Newton and A. W. Philips. Plates 14-37, 97 Art. V. On the equilibrium of heterogeneous sub- stances. By J. W. Gibbs. First Part, 108 Art. VI. The Hydroids of the Pacific coast of the United States south of Vancouver Island, with a report upon those in the Museum of Yale Coixege. By S. F. Clark. Plates 38-41, 249 Art. VII. On the anatomy and habits of Nereis virens. By Y. M, Turnbull. Plates 42-44, 265 Art. VIII. Median and paired fins, a contribution to the history of vertebrate limbs. By J. K. Thacher, Plates 49-60, 281 Art. IX. Early stages op Hippa talpoida, with a note ON THE structure OF THE MANDIBLES AND MAXILLJE IN Hipp A and Remipes. By S. I. Smith. Plates 45-48, 311 Art. -

The Victorian Global Positioning System by Trudy E

The Victorian Global Positioning System by Trudy E. Bell TARS GLEAMED OVERHEAD in a velvet-black With this vivid account, published immediately in the sky on a crisp October night in 1848 as six astrono- Cincinnati Observatory’s periodical The Sidereal Messen- mers entered the darkened dome of the three- ger, Mitchel affords an eyewitness’s glimpse into one of the year-old Cincinnati Observatory. Seating them- great untold stories in the histories of telegraphy, as- s selves around a table laden with several large tronomy, and geodesy: the telegraphic method of deter- batteries and clocks, Ormsby McKnight Mitchel, the mining longitudes. observatory’s director, was keenly aware of the moment’s Within a few short years, the telegraph had transformed historic significance. About 9 p.m., the men were joined by a both positional astronomy and geodesy. The telegraphic telegraph operator who, Mitchel wrote, method of determining longitudes held sway for eight decades not only in the . perfected the necessary arrange- United States but also in Europe—be- ments for communicating directly by ing replaced only in the 1920s by radio telegraph between the Cincinnati The telegraph (wireless) positioning techniques. Yet Observatory and the Philadelphia its history appears to have been largely [Central High School] Observatory. was as revolutionary overlooked, including in two recent At ten o’clock the way offices along for determining popular bestsellers on the measure- the line were closed, and the line of ment of longitude and on the telegraph.1 the telegraph given up to the use of longitude on land the astronomers. The novelty of the as the marine WHY A DEMAND FOR operations excited the deepest inter- chronometer was LONGITUDES? est among all who were present. -

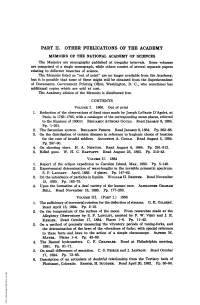

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS of the ACADEMY MEMOIRS of the NATIONAL ACADEMY of SCIENCES -The Memoirs Are Monographs Published at Irregular Intervals

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS OF THE ACADEMY MEMOIRS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES -The Memoirs are monographs published at irregular intervals. Some volumes are comprised of a single monograph, while others consist of several separate papers relating to different branches of science. The Memoirs listed as "out of print" qare no longer available from the Academy,' but it is possible that some of these might still be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., who sometimes has additional copies which are sold at cost. The Academy edition of the Memoirs is distributed free. CONTENTS VoLums I. 1866. Out of print 1. Reduction of the observations of fixed stars made by Joseph LePaute D'Agelet, at Paris, in 1783-1785, with a catalogue of the corresponding mean places, referred to the Equinox of 1800.0. BENJAMIN APTHORP GOULD. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 1-261. 2. The Saturnian system. BZNJAMIN Pumcu. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 263-86. 3. On the distribution of certain diseases in reference to hygienic choice of location for the cure of invalid soldiers. AUGUSTrUS A. GouLD. Read August 5, 1864. Pp. 287-90. 4. On shooting stars. H. A. NEWTON.- Read August 6, 1864. Pp. 291-312. 5. Rifled guns. W. H. C. BARTL*rT. Read August 25, 1865. Pp. 313-43. VoLums II. 1884 1. Report of the eclipse expedition to Caroline Island, May, 1883. Pp. 5-146. 2. Experimental determination of wave-lengths in the invisible prismatic spectrum. S. P. LANGIXY. April, 1883. 4 plates. Pp. 147-2. -

Prof. E. Loomis on the Aurora of 1859. by ELIAS LOOMIS

318 Prof. E. Loomis on the Aurora of 1859. ART. XXXVI.-On the great Auroml Exhibition of Aug. 28th to &pt. 4th, 1859, arid on Auroras generally.-8TH ARTICLE; by ELIAS LOOMIS, Professor of Natural Philosophy and As tronomy in Yale College. SINCE the publication of my seventh article on t11e great auroral exhibition of Aug. 28th to Sept 4th, 1859, I have received from Prof. Hansteen a copy of the observations made at Christiania, Norway, corresponding to those made at Hobarton, as given in this Journal, vol. xxxii, p 81. These observations are published in the Memoires del'Academie de Belgique, tome xx, pp. 103-116, and Bulletins de l'Academie Royale de Belgique, tome xxi, pp. 284-298. Observations of the Aurora at Ohristiania, Nortoay, lat. 59° 54', long. 10° 43' E. Magnetic dip in 1S59, 71° IS'. ~ . Day. Hour. Notic•• of Auror••. 1841. Mllrcb Iii, IOh Aurora. Mluch 22, Rllin. Mny 17, Rain. July 20. No lLurora visible. 1842. Feb. 18, 11-14 A urora faint. April II. 9-15 8light aurora. Faint arch at llih. April 12. 9-14 Rays and flllmes extendiug to the zenith. April 13. 9-13 Rays and flames. April 15. 11-15 Flaming aurora. July 2. 10 and 12 The bi/Har magnetometer was quite out of Reale. 1844. April 17, 9 Faint aurora. extending nearly to the zenith. 1846. Sept. 22, '1-15 Vehement flames o"er three· fourths of the heavens. Redtlish. Corona imperfect. 184'1. April 21, 11-14 Flaming and radiating aurora. Sept. 24, 7-10 Corona formed. -

South American Auroral Reports During the Carrington Storm Hisashi Hayakawa1,2,3,4* , José R

Hayakawa et al. Earth, Planets and Space (2020) 72:122 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01249-4 EXPRESS LETTER Open Access South American auroral reports during the Carrington storm Hisashi Hayakawa1,2,3,4* , José R. Ribeiro5 , Yusuke Ebihara6,7 , Ana P. Correia5 and Mitsuru Sôma8 Abstract The importance of the investigation of magnetic superstorms is not limited to academic interest, because these superstorms can cause catastrophic impact on the modern civilisation due to our increasing dependency on techno- logical infrastructure. In this context, the Carrington storm in September 1859 is considered as a benchmark of obser- vational history owing to its magnetic disturbance and equatorial extent of the auroral oval. So far, several recent auroral reports at that time have been published but those reports are mainly derived from the Northern Hemi- sphere. In this study, we analyse datable auroral reports from South America and its vicinity, assess the auroral extent using philological and astrometric approaches, identify the auroral visibility at 17.3° magnetic latitude and further poleward and reconstruct the equatorial boundary of the auroral oval to be 25.1°− 0.5° in invariant latitude. Interest- ingly, brighter and more colourful auroral displays were reported in the South American± sector than in the Northern Hemisphere. This north–south asymmetry is presumably associated with variations of their magnetic longitude and the weaker magnetic feld over South America compared to the magnetic conjugate point and the increased amount of magnetospheric electron precipitation into the upper atmosphere. These results attest that the magnitude of the Carrington storm indicates that its extent falls within the range of other superstorms, such as those that occurred in May 1921 and February 1872, in terms of the equatorial boundary of the auroral oval.