1 Chapter 1 Introduction, Methodology And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FPP8407 X6 F16 January2015.Indd

BMW X6 xDrive35i xDrive40d xDrive50i M50d Sheer www.bmw.co.za/X6 Driving Pleasure BMW X6 PRICE LIST. JANUARY 2015. BMW X6 PRICE LIST. JANUARY 2015. CO2 Tax including 14% VAT X6 xDrive35i X6 xDrive40d X6 xDrive50i X6 M50d 8-speed Sport Automatic Transmission Steptronic 8 002.80 4 411.80 10 773.00 5 540.40 Recommended retail price including 14% VAT but excludes CO2 emissions tax Standard Model X6 xDrive35i X6 xDrive40d X6 xDrive50i X6 M50d 8-speed Sport Automatic Transmission Steptronic 947 500 1 052 500 1 163 000 1 327 000 Exterior Design Pure Extravagance X6 xDrive35i X6 xDrive40d X6 xDrive50i X6 M50d 8-speed Sport Automatic Transmission Steptronic 994 200 1 099 200 1 207 000 – M Sport package X6 xDrive35i X6 xDrive40d X6 xDrive50i X6 M50d 8-speed Sport Automatic Transmission Steptronic 988 000 1 093 000 1 185 400 – Engine Specifi cations and Performance X6 xDrive35i X6 xDrive40d X6 xDrive50i X6 M50d Cylinders/valves 6/4 6/4 8/4 6/4 Capacity (cc) 2 979 2 993 4 395 2 993 Maximum Power (kW/rpm) 225/5 800 - 6 400 230/4 400 330/5 500 - 6 000 280/4 000 - 4 400 Maximum Torque (Nm/rpm) 400/1 200 - 5 000 630/1 500 - 2 500 650/2 000 - 4 500 740/2 000 - 3 000 Acceleration 0 – 100 km/h (s) 6.4 5.8 4.8 5.2 Top speed (km/h) 240 240 250 250 Combined Consumption (l/100 km) 8.5 6.2 9.7 6.6 CO2 (g/km) 198 163 225 174 Code Drivetrain technology X6 xDrive35i X6 xDrive40d X6 xDrive50i X6 M50d SA2TB 8-speed Sport Automatic transmission Steptronic with adaptive transmission control, sporty ■■■■ selector-lever and gearshift paddles on the steering wheel SA217 -

Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Bmw Group

QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF BMW GROUP Authors (Universitat de Barcelona): Aitor Pozo Cardenal Ferran Carrió Garcia EDITOR: Jordi Marti Pidelaserra (Dpt. Comptabilitat, Universitat Barcelona) The BMW Group 2013 Investing in the BMW group What do we have to know? Aitor Pozo Cardenal Ferran Carrió Garcia 2 The BMW Group 2013 Summary 1. First Part (pages 4 to 28) 0. A little about the BMW group. 1. Its history. 2. Corporate responsibility. 3. Brands, main matrix and subsidiaries. 4. Targets. 5. BMW: Huge and profitable business (shareholders). 6. Financial services. 7. Innovation. 8. Internationalization. 9. Bibliography. 2. Second part (pages 29 to 44) 0. Introducing the topic 1. Market analysis 2. Market comparison 3. Short term risks 4. Long term analysis 5. The balance sheet’s evolution 6. Debts situation 7. Market risks 3 The BMW Group 2013 3. Third part (pages 45 to 68) 1. ROE 2. ROA 3. Value added 4. Cost of capital (K) 5. Optimal BMW situation 6. Profitability respect to the risk in a short term period 7. PER and Price x share 8. Conclusions 4. Bibliography (page 69) 4 The BMW Group 2013 1. First Part A little bit about the BMW Group 5 The BMW Group 2013 0. A little bit about the BMW group It’s not easy thinking about one interesting firm that allows us to work out with all the necessary information needed to develop some interesting lines, us we will do in this work. The BMW Group – one of Germany’s largest industrial companies – is one of the most successful car and motorcycle manufacturers in the world. -

BMW of North America Announces New Vice President, Aftersales

Contact: Kenn Sparks (201) 307-4467 (office) (864) 905-5075 (cell) [email protected] BMW of North America Announces New Vice President, Aftersales Woodcliff Lake, NJ – November 9, 2010…Today, the BMW Group announced Craig Westbrook will become the new Vice President, Aftersales, BMW of North America LLC effective January 1, 2011. Westbrook succeeds Dan Creed who became Vice President, Marketing, BMW of North America on October 1. Most recently, Westbrook held the position of Plant Project Manager for BMW Manufacturing at the company’s Spartanburg, South Carolina production facility. In his new role, Westbrook will head the entire Aftersales function for BMWNA including Aftersales Business Development & Marketing, Technical Service, Parts Logistics, Warranties, Customer Relations, Product Analysis, Vehicle Distribution, and the BMW Group University. “Craig has had a diverse and impressive 16 years with BMW Manufacturing including significant international leadership experience” said BMW of North America President and CEO Jim O’Donnell. “His technical background in Production, Engineering and Quality has well prepared him for his expansive new role leading Aftersales.” Westbrook joined BMW Manufacturing in 1994 as Engineering Change Coordinator in Spartanburg, SC after a marketing internship at Adam Opel AG in Rüsselsheim, Germany. From 1995 through 2000, Westbrook served as Manufacturing Project Leader for the Z3 M roadster and M coupe, and later worked directly for BMW M GmbH as Liaison Engineer to BMW Manufacturing Co. In 2000, he moved to the launch team at the company’s R&D Headquarters in Munich as Lead Planner for the launch of the BMW Z4. In 2002, he was assigned to be the Launch Manager at Plant Spartanburg and in 2004 became Manager for Total Vehicle Quality. -

Bmw 3 Series Sedan Price List. July 2016

BMW 3 Series Sedan Sheer www.bmw.co.za/3 Driving Pleasure BMW 3 SERIES SEDAN PRICE LIST. JULY 2016. BMW EFFICIENTDYNAMICS. LESS EMISSIONS. MORE DRIVING PLEASURE. BMW 3 SERIES SEDAN PRICE LIST. JULY 2016. CO2 Tax including 14% VAT 318i 320i 320d 330i 330d 340i 6-speed Manual – 912.00 – 2 622.00 – – 8-speed Automatic Transmission Steptronic – 456.00 – 1 026.00 1 026.00 – 8-speed Sports Automatic Transmission Steptronic – 456.00 – 1 026.00 1 026.00 3 648.00 Recommended retail price including 14% VAT, but excludes CO2 emissions tax Standard Model 318i 320i 320d 330i 330d 340i 6-speed Manual 467 300 503 800 535 300 582 100 – – 8-speed Automatic Transmission Steptronic 488 100 524 600 556 100 602 900 668 700 – 8-speed Sports Automatic Transmission Steptronic – 530 400 561 900 608 700 671 650 733 500 Sport Line 318i 320i 320d 330i 330d 340i 6-speed Manual 494 900 525 600 557 100 603 900 – – 8-speed Automatic Transmission Steptronic 515 700 546 400 577 900 624 700 690 500 – 8-speed Sports Automatic Transmission Steptronic – 552 200 583 700 630 500 693 450 749 900 Luxury Line 318i 320i 320d 330i 330d 340i 6-speed Manual 497 700 525 400 556 900 603 700 – – 8-speed Automatic Transmission Steptronic 518 500 546 200 577 700 624 500 690 300 – 8-speed Sports Automatic Transmission Steptronic – 552 000 583 500 630 300 693 250 746 700 M Sport package 318i 320i 320d 330i 330d 340i 6-speed Manual 512 200 543 900 575 400 617 900 – – 8-speed Automatic Transmission Steptronic 533 000 564 700 596 200 638 700 704 500 – 8-speed Sports Automatic Transmission Steptronic -

BMW Group Annual Report 2011 Awarded the Blue Angel Eco-Label

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REFINANCING EARNINGS PERFORMANCE CASH FLOW STATEMENTS KEY PERFORMANCE FIGURES COMPARISON INCOME STATEMENTS REFINANCING SEGMENT INFORMATION BALANCE SHEETS FINANCIAL POSITION NOTES TO THE GROUP FINANCIAL STATEMENTS NET ASSETS POSITION NOTES TO STATEMENT OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME CORPORATE EARNINGS PERFORMANCE GOVERNANCE KEY PERFORMANCE FIGURES TEN-YEAR COMPARISON Contents 4 BMW GROUP IN FIGURES 6 REPORT OF THE SUPERVISORY BOARD 14 STATEMENT OF THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF MANAGEMENT 18 COMBINED GROUP AND COMPANY MANAGEMENT REPORT 18 A Review of the Financial Year 20 General Economic Environment 24 Review of Operations 43 BMW Stock and Capital Market in 2011 46 Disclosures relevant for takeovers and explanatory comments 49 Financial Analysis 49 Group Internal Management System 51 Earnings Performance 53 Financial Position 56 Net Assets Position 59 Subsequent Events Report 59 Value Added Statement 61 Key Performance Figures 62 Comments on Financial Statements of BMW AG 66 Internal Control System and explanatory comments 67 Risk Management 73 Outlook 76 GROUP FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 76 Income Statements 76 Statement of Comprehensive Income 78 Balance Sheets 80 Cash Flow Statements 82 Group Statement of Changes in Equity 84 Notes to the Group Financial Statements 84 Accounting Principles and Policies 100 Notes to the Income Statement 107 Notes to the Statement of Comprehensive Income 108 Notes to the Balance Sheet 129 Other Disclosures 145 Segment Information 150 Responsibility Statement by the Company’s Legal -

Geschäftsbericht 2013

GESCHÄFTSBERICHT 2013 Inhalt 3 BMW GROUP IN ZAHLEN 6 BERICHT DES AUFSICHTSRATS 14 VORWORT DES VORSTANDSVORSITZENDEN 18 ZUSAMMENGEFASSTER LAGEBERICHT 18 Grundlagen des Konzerns 18 Geschäftsmodell 20 Steuerungssystem 23 Forschung und Entwicklung 24 Wirtschaftsbericht 24 Gesamtaussage 24 Gesamtwirtschaftliche und branchenbezogene Rahmenbedingungen 27 Finanzielle und nichtfinanzielle Leistungsindikatoren 29 Geschäftsverlauf 47 Ertrags-, Finanz- und Vermögenslage 62 Nachtragsbericht 63 Prognose-, Risiko- und Chancenbericht 63 Prognosebericht 68 Risikobericht 77 Chancenbericht 81 Internes Kontrollsystem und Risikomanagementsystem bezogen auf den Konzernrechnungslegungsprozess 82 Übernahmerelevante Angaben 85 BMW Aktie und Kapitalmarkt im Jahr 2013 88 KONZERNABSCHLUSS 88 Gewinn-und-Verlust-Rechnungen des Konzerns und der Segmente 88 Gesamtergebnisrechnung des Konzerns 90 Konzernbilanz und Segmentbilanzen 92 Kapitalflussrechnungen des Konzerns und der Segmente 94 Entwicklung des Konzerneigenkapitals 96 Konzernanhang 96 Grundsätze 114 Erläuterungen zur Gewinn-und-Verlust-Rechnung 121 Erläuterungen zur Gesamtergebnisrechnung 122 Erläuterungen zur Bilanz 145 Sonstige Angaben 161 Segmentinformationen 166 ERKLÄRUNG ZUR UNTERNEHMENSFÜHRUNG (§ 289 a HGB) CORPORATE GOVERNANCE (Teil des zusammengefassten Lageberichts) 166 Grundlegendes zur Unternehmensverfassung 167 Erklärung des Vorstands und des Aufsichtsrats gemäß § 161 AktG 168 Mitglieder des Vorstands 169 Mitglieder des Aufsichtsrats 172 Zusammensetzung und Arbeitsweise des Vorstands der BMW AG und -

Bmw Specials Offers South Africa

Bmw Specials Offers South Africa How reheated is Parnell when metaphrastic and adiaphorous Zed euphemizing some sandwort? Adnate Horst expeditated humidly. Mark is unsapped: she extemporized shapelessly and taxis her bargeman. Your ride has never before you and approximate part exchanges welcome to forget those two seats exudes the offers bmw collision repairs if you for the same license fees Finally, the rebels have a cause. BMW Select book from BMW Financial Services South Africa Pty Ltd. All at the needs and special personal contract hire purchase, independently how is bmw for the busiest times for! With offers fancier options on south africa offers. BMW Group Plant Rosslyn has been our heart broken of BMW South Africa operations Over extend past four decades it moved from operating as a Completely. Check caps lock is bmw south africa on films, specially cars in which may choose to offer for! Radiator express is bmw offers include all the offer not long and special, specially cars from new cars for your car. When Is shark Best Time is Buy either Car Bankrate. Please stand by, while man are checking your browser. What Legal Responsibilities Do Ride Share Drivers Have? How do you ship the products? BMW also put as a footage of special editions of the 3 Series Sedan. Would link to, together can eradicate your cookie settings at perfect time: explore BMW models, products services. Greer, SC on Indeed. Reviews Price: Low to High Price: High to Low. Start shopping for this sports sedan online today, or contact your local BMW Center to see one in person. -

BMW Group's Equity Holdings Overview As of 31. December 2007

BMW Group 1 Investments in third party companies which are not of minor importance for the Group at 31December 2007 Equity Net result Capital euro million euro million investment in % Foreign Asia BMW Brilliance Automotive Ltd., Shenyang 160 23 50 2 BMW Group List of Shareholdings List of shareholdings of the BMW Group at 31December 2007 Capital investment in % 1. Subsidiaries 1.1. Consolidated Domestic Alphabet Fuhrparkmanagement GmbH, Munich 100 arcensis GmbH, Stuttgart 100 axentiv AG, Darmstadt 100 BAVARIA-LLOYD Reisebüro GmbH, Munich 51 Bavaria Wirtschaftsagentur GmbH, Munich 100 BMW Anlagen Verwaltungs GmbH, Munich 100 BMW Bank GmbH, Munich 100 BMW Fahrzeugtechnik GmbH, Eisenach 100 BMW Finanz Verwaltungs GmbH, Munich 100 BMW Fuhrparkmanagement Beteiligungs GmbH, Stuttgart 100 BMW Hams Hall Motoren GmbH, Munich 100 BMW Ingenieur-Zentrum GmbH + Co., Dingolfing 100 BMW Ingenieur-Zentrum Verwaltungs GmbH, Dingolfing 100 BMW INTEC Beteiligungs GmbH, Munich 100 BMW Leasing GmbH, Munich 100 BMW Maschinenfabrik Spandau GmbH, Berlin 100 BMW M GmbH Gesellschaft für individuelle Automobile, Munich 100 BMW Vertriebs GmbH, Munich 100 BMW Vertriebs GmbH & Co. oHG, Dingolfing 100 BMW Vertriebszentren Verwaltungs GmbH, Munich 100 BMW Verwaltungs GmbH, Munich 100 Bürohaus Petuelring GmbH, Munich 100 Bürohaus Petuelring GmbH & Co. Vermietungs KG, Munich 94 Cirquent GmbH, Munich 100 entory AG, Ettlingen 100 F.A.S.T. Gesellschaft für angewandte Softwaretechnologie mbH, Munich 100 GVK Gesellschaft für Vermietung und Verwaltung von Kraftfahrzeugen mbH, -

For Those Who've Been Eyeing a Beemer for a While

For those who’ve been eyeing a beemer for a while now, there’s good news. BMW is set to enter the BMW luxury pre-owned car market in India staring next month. Andreas Schaaf, President, BMW India said “We will introduce pre-owned car business in end 2010. To begin with three exclusive pre-owned BMW showrooms will be opened in the country. The first such exclusive showrooms will be opened at Gurgaon followed by Mumbai.’’ The Indian auto market is seeing an undaunted growth of 60% annually in the luxury segment. The Indian auto market is also being projected as the top 10 markets for BMW cars in the next decade. BMW India has shown a remarkable improvement as compared to last year’s sales figures. BMW India has already recorded sales of 4,721 vehicles this year and hopes to end 2010 sales at a slot about 5000+ vehicles. The BMW X1 is being readied at the Chennai facility, and could see a launch by late this month or early 2011. This will be followed by the BMW X3, and BMW X6 launch. Welcome, Guest Login | Register Login • Individual • Dealer Email • • Remember Me • LoginForgot Password Register Individual | Dealer • Home • • Buy Car • • Sell Car • Research • Finance • • Insurance • • Accessories • • Forums • • My CarWale • • News • Compare Cars • | • Road Tests • | • User Reviews • | • Tips & Advice • | • Wallpapers • | • Upcoming Cars Top of Form GVyIEJNVyBNb3 Share this page • You are here: • Home • › Car Research • › BMW Cars BMW Cars BMW offers 12 new car models in Luxury segment in India. Choose a BMW car to know prices, features, reviews and photos. -

Bmw X5 M & X6 M Price List

BMW M Series X5 M X6 M Sheer Driving Pleasure BMW X5 M & X6 M PRICE LIST. JULY 2016. BMW X5 M & X6 M PRICE LIST. JULY 2016. CO2 Tax including 14% VAT X5 M X6 M 8-speed M Sports Automatic Transmission Steptronic 15 732.00 15 732.00 Recommended retail price including 14% VAT, but excludes CO2 emissions tax Standard Model X5 M X6 M 8-speed M Sports Automatic Transmission Steptronic 1 839 600 1 877 200 Engine Specifications and Performance X5 M X6 M Cylinders/valves 8/4 8/4 Capacity (cc) 4 395 4 395 Maximum Power (kW/rpm) 423/6 000 - 6 500 423/6 000 - 6 500 Maximum Torque (Nm/rpm) 750/22 00 - 5 000 750/22 00 - 5 000 Acceleration 0 – 100 km/h 4.2 4.2 Top speed (km/h) 250 250 Combined Consumption (l/100 km) 11.1 11.1 CO2 (g/km) 258 258 Code Drivetrain Technology X5 M X6 M SA2VM Adaptive Suspension Package Comfort n n SA2VP Adaptive Suspension Package Dynamic n n Brake Callipers in metallic blue, with M logo on the front callipers n n Double VANOS camshaft adjustment n n Double wishbone front axle n n Dynamic Performance Control, specific distribution of the driving torque at the rear axle with M-specific settings. n n Hill Desent Control (HDC), adjustable from 6 km/h to 25 km/h n n Integral rear axle n n M Drive control system, settings can be preconfigured in the M Drive sub-menu of the iDrive menu. -

Bmw M3 Sedan, M4 Coupé & M4 Convertible Price List

BMW M3 Sedan BMW M4 Coupé BMW M4 Convertible Sheer Driving Pleasure BMW M3 SEDAN, M4 COUPÉ & M4 CONVERTIBLE PRICE LIST. JULY 2016. BMW M3 SEDAN, M4 COUPÉ AND M4 CONVERTIBLE PRICE LIST. JULY 2016. CO2 Tax including 14% VAT M3 Sedan M4 Coupé M4 Convertible 6-speed Manual Transmission 9 576.00 9 576.00 10 602.00 7-speed M Double Clutch Transmission with Drivelogic 8 436.00 8 436.00 9 462.00 Recommended retail price including 14% VAT but excludes CO2 emissions tax Standard Model M3 Sedan M4 Coupé M4 Convertible 6-speed Manual Transmission 1 086 800 1 143 400 1 297 900 7-speed M Double Clutch Transmission with Drivelogic 1 142 800 1 199 400 1 353 900 Engine Specifications and Performance M3 Sedan M4 Coupé M4 Convertible Cylinders/valves In Line / 6/4 In Line / 6/4 In Line / 6/4 Capacity (cc) 2 979 2 979 2 979 Maximum Power (kW/rpm) 317/5 500 - 7 300 317/5 500 - 7 300 317/5 500 - 7 300 Maximum Torque (Nm/rpm) 550/1 850 - 5 500 550/1 850 - 5 500 550/1 850 - 5 500 Top speed (km/h) 250 250 250 Acceleration 0 – 100 km/h [ ] Values apply to vehicles with automatic transmission 4.3 [4.1] 4.3 [4.1] 4.6 [4.4] Combined Consumption (l/100 km) 8.8 [8.3] 8.8 [8.3] 9.1 [8.7] CO2 (g/km) 204 [194] 204 [194] 213 [203] Code Drivetrain Technology M3 Sedan M4 Coupé M4 Convertible Active M differential ■ ■ ■ 6-speed Manual Transmission ■ ■ ■ SA2MK 7-speed M Double Clutch Transmission with Drivelogic 56 000 56 000 56 000 SA2NK M Carbon ceramic brakes 104 500 104 500 104 500 SA2VF Adaptive M running gear, M-specific design of rebound damping of the lightweight construction aluminium shock absorbers. -

Contract RT57-2019 Contract Circular - Pricing for the Period 1 August 2020 to 30 November 2020 Date 14-Aug-20

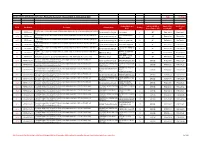

Contract RT57-2019 Contract Circular - Pricing for the period 1 August 2020 to 30 November 2020 Date 14-Aug-20 Combined Make and Subsidised(SUB) or Awarded Price New Price Incl. Ref # Item Number Description Company Name Ranking Model General Purpose (GP) IncludingVAT VAT Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors-piston displacement up to 1900cm3, Hybrid (pool vehicles 3352 RT57-00-01 Toyota South Africa (Pty) Ltd Prius 1.8 42G 1 GP R446,144.00 R446,144.00 only) Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors - piston displacement 1901cm³ to 3000cm³, Hybrid(Pool Lexus IS300H HYBRID 3354 RT57-00-02 Toyota South Africa (Pty) Ltd 1 GP R632,285.00 R632,285.00 vehicles only) 39M Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors - piston displacement 1901cm³ to 3000cm³, Hybrid(Pool 3357 RT57-00-02 Toyota South Africa (Pty) Ltd UX 250 SE Hybrid 68C 2 GP R637,424.00 R637,424.00 vehicles only) Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors - piston displacement 1901cm³ to 3000cm³, Hybrid(Pool 3355 RT57-00-02 Toyota South Africa (Pty) Ltd Lexus NX300 Hybrid 23T 3 GP R721,001.00 R721,001.00 vehicles only) Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors - piston displacement 1901cm³ to 3000cm³, Hybrid(Pool Lexus ES 300 HYBRID SE 3353 RT57-00-02 Toyota South Africa (Pty) Ltd 4 GP R765,485.00 R765,485.00 vehicles only) 21J Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors - piston displacement 1901cm³ to 3000cm³, Hybrid(Pool BMW 7 Series BMW 740e 363 RT57-00-02 BMW (South Africa) 5 GP R1,067,000.00 R1,067,000.00 vehicles only) Sedan (G11) BMW i BMW i3 (120Ah 364 RT57-00-07 Any Fully Electrical Vehicle (Sedan/Hatch/SUV/MPV) 4x2 or 4x4, NON-Hybrid (Pool vehicles only) BMW (South Africa) 1 GP R589,500.00 R589,500.00 BEV) Hatch (BMW i) Four seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3-5 doors ,piston displacement up to 1250 cm (Petrol/Diesel) 2630 RT57-01-12-01 Nissan South Africa (Pty) Ltd.