A Case Study of the Ecology of British Breeding Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5.4. Changes in the Bird Communities of Sierra Nevada Zamora ,R.1 and Barea-Azcón, J.M.2 1 Andalusian Institute for Earth System Research

5.4. Changes in the bird communities of Sierra Nevada Zamora ,R.1 and Barea-Azcón, J.M.2 1 Andalusian Institute for Earth System Research. University of Granada 2 Environment and Water Agency of Andalusia Abstract The changes in the composition and abundance of passerine communities were studied along an elevational gradient, comparing the results found by censuses made in three different habitats (oak forest, high-mountain juniper scrublands, and high-mountain summits) at the beginning of the 1980s and at present. The results indicate that in the last 30 years, notable changes have taken place in the composition and, especially, in the abundance of the passerine communities. Significant declines in populations were appreciated in many of the species that were dominant in the 1980s, particularly in oak forests and in high-mountain juniper scrublands. The magnitude of the changes diminishes with elevation, and therefore the ecosystem that has changed the most was the oak woodland and those that changed the least were the ecosystems of the high-summits. The bird communities in Sierra Nevada showed a strong spatio-temporal dynamic that appears to be accentuated by global change. Aims and methodology The censuses of reproductive birds compiled censuses were made along linear transects with [13 - 17]. The current censuses were undertaken at the beginning of the 1980s and at present a fixed bandwidth of 50 m, 25 m on each side of within the framework of the Sierra Nevada (2008-2012) were compared. The sites studied the observer. The sampling effort was similar in Global Change Observatory from 2008 to 2012, were the same in both periods: an oak forest both periods. -

Hungary & Transylvania

Although we had many exciting birds, the ‘Bird of the trip’ was Wallcreeper in 2015. (János Oláh) HUNGARY & TRANSYLVANIA 14 – 23 MAY 2015 LEADER: JÁNOS OLÁH Central and Eastern Europe has a great variety of bird species including lots of special ones but at the same time also offers a fantastic variety of different habitats and scenery as well as the long and exciting history of the area. Birdquest has operated tours to Hungary since 1991, being one of the few pioneers to enter the eastern block. The tour itinerary has been changed a few times but nowadays the combination of Hungary and Transylvania seems to be a settled and well established one and offers an amazing list of European birds. This tour is a very good introduction to birders visiting Europe for the first time but also offers some difficult-to-see birds for those who birded the continent before. We had several tour highlights on this recent tour but certainly the displaying Great Bustards, a majestic pair of Eastern Imperial Eagle, the mighty Saker, the handsome Red-footed Falcon, a hunting Peregrine, the shy Capercaillie, the elusive Little Crake and Corncrake, the enigmatic Ural Owl, the declining White-backed Woodpecker, the skulking River and Barred Warblers, a rare Sombre Tit, which was a write-in, the fluty Red-breasted and Collared Flycatchers and the stunning Wallcreeper will be long remembered. We recorded a total of 214 species on this short tour, which is a respectable tally for Europe. Amongst these we had 18 species of raptors, 6 species of owls, 9 species of woodpeckers and 15 species of warblers seen! Our mammal highlight was undoubtedly the superb views of Carpathian Brown Bears of which we saw ten on a single afternoon! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Hungary & Transylvania 2015 www.birdquest-tours.com We also had a nice overview of the different habitats of a Carpathian transect from the Great Hungarian Plain through the deciduous woodlands of the Carpathian foothills to the higher conifer-covered mountains. -

Belarus in Spring

Belarus in Spring Naturetrek Tour Report 6 - 13 May 2012 Report compiled by Attila Steiner Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Belarus in Spring Tour leaders: Attila Steiner Alexander Duka Participants: Elizabeth Briggs David Briggs Colin Hughes John Skeavington Jillian Bale Roberta Goodall Day 1 Sunday 6th May UK – Minsk – Liaskavichi Our flight from London arrived on time at Minsk International Airport. At the arrival hall Attila and Alexander greeted us. After changing money we had a tasty dinner at the airport restaurant. Then we started the long drive to our first hotel situated on the edge of the famous Pripiat National Park. We arrived at our hotel in Liaskavichi after midnight. After checking in some of us could hear Thrush Nightingale singing and Spotted Crakes calling from the nearby wetland. Day 2 Monday 7th May Liaskavich area of Pripiat National Park It was already sunny and hot outside when we gathered at the minivan ready to explore nearby woodlands and wetlands. As we drove through Liaskavichi we saw our first White Stork nest, one of the hundreds to be seen during the week. Our first stop along the road was for a raptor circling above the fields, which proved to be a Lesser Spotted Eagle. We soon left the main road and took a gravel road towards the woodlands. We stopped to watch a Black Kite flying above the forest. It then landed on top of a dead tree and we had prolonged scope views of this nice raptor. -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

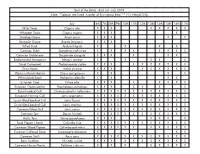

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Birds of Latvia

Birds of Latvia Checklist with remarks about species occurrence All species known to have occured in Latvia are listed in systematic order (based on Voous sequence) following guidelines of Association of European Rarities Committees. The key to each abbreviated status is as follows. Small letters rather than capitals signify a scarcer distribution - less than 10 records for Latvia until 16.08.2010. The avifauna of Latvia includes a total of 344 species. Place for subspecies or new entries you will find at the end of this list. CB - casual breeder MB - migrant breeder PM - passage migrant RB - resident breeder WV - winter visitor SV - summer visitor V - vagrant E - escaped or recently introduced Name, route, dates etc. Categories used for the national list: Category A - species which has been recorded in an apparently wild state at least once since 1.1.1950 [Majority of the species - are not marked in the categories’ column]. Category B - species which has been recorded in an apparently wild state only between 1800 and 1949 Category C - released or escaped species which has established a self-supporting breeding population in the own country; also birds coming from a category C population of another country (with the species not breeding in the own country). ----------------------------------------- Category D - every species unless it is almost certainly a genuine vagrant (in which case it enters Cat. A), or almost certainly an escape from captivity (Cat. E). Here also these species, which has been found dead at the sea-shore and there is doubt about their death within Latvian territory or beyond. -

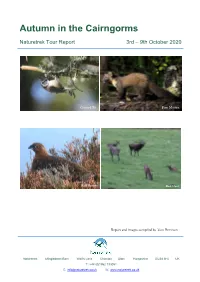

Tour Report 3Rd – 9Th October 2020

Autumn in the Cairngorms Naturetrek Tour Report 3rd – 9th October 2020 Crested Tit Pine Marten Red Grouse Red Deer Report and images compiled by Tom Brereton Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Autumn in the Cairngorms Tour participants: Tom Brereton (Leader) with five Naturetrek clients Day 1 Saturday 3rd October The trip started with the collection of four clients from a dull and rainy Inverness Airport. En route to our afternoon destination, we made a brief stop at Alturie located along the southern margin of the Moray Firth east of Inverness, where there were numerous coastal wildfowl including Wigeon, Teal, Eider and best of all a Slavonian Grebe. A Hooded Crow was also seen. We also stopped at a supermarket nearby to buy some goodies for the trip mainly in the form of drinks for evenings at the guest house. We then drove on to Insh Marhses RSPB where we met the other guest on this holiday. Insh is a wonderful reserve for all forms of wildlife including fungi, and there were several Fly Agaric visible under woodland right by the car park. During the afternoon we made a short walk to the two hides picking up en route Goldcrest and Redwing. From the hides, we saw Roe Deer, Teal, Oystercatcher, Snipe, Grey Heron and a small flock of Swallow . Late afternoon, after a tiring day of travel, we headed to our accommodation for the holiday, Ballintean Mountain Lodge, fabulously located in beautiful Glenfeshie. -

The Contribution to Wildlife Conservation of an Italian Recovery

Nature Conservation 44: 1–20 (2021) A peer-reviewed open-access journal doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.44.65528 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://natureconservation.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity conservation The contribution to wildlife conservation of an Italian Recovery Centre Gabriele Dessalvi1, Enrico Borgo2, Loris Galli1 1 Department of Earth, Environmental and Life Sciences (DISTAV), Genoa University, Corso Europa 26, 16132, Genoa, Italy 2 Museum of Natural History “Giacomo Doria”, Via Brigata Liguria, 9, 16121, Genoa, Italy Corresponding author: Loris Galli ([email protected]) Academic editor: Christoph Knogge | Received 5 March 2021 | Accepted 20 April 2021 | Published 10 May 2021 http://zoobank.org/F5D4BBF2-A839-4435-A1BA-83EAF4BA94A9 Citation: Dessalvi G, Borgo E, Galli L (2021) The contribution to wildlife conservation of an Italian Recovery Centre. Nature Conservation 44: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.44.65528 Abstract Wildlife recovery centres are widespread worldwide and their goal is the rehabilitation of wildlife and the subsequent release of healthy animals to appropriate habitats in the wild. The activity of the Genoese Wild- life Recovery Centre (CRAS) from 2015 to 2020 was analysed to assess its contribution to the conservation of biodiversity and to determine the main factors affecting the survival rate of the most abundant species. In particular, the analyses focused upon the cause, provenance and species of hospitalised animals, the sea- sonal distribution of recoveries and the outcomes of hospitalisation in the different species. In addition, an in-depth analysis of the anthropogenic causes was conducted, with a particular focus on attempts of preda- tion by domestic animals, especially cats. -

Window Birds, Cutwork, Paris 2020, ENG Hq

Urban Ornithology : Window Birds Cities & Living Beings Cutwork France Paris Office Contact Web 23 rue d’Anjou 6 Avenue René Coty [email protected] cutworkstudio.com 1 / 68 75008 Paris, FR 75014 Paris, FR +31 6 41 17 69 45 instagram: @cutwork Paris | April 2020 To see… 1. Everywhere …………….. 4 2. Trees / Parks …………… 21 3. Water ………………………. 40 4. Seasonal …………………. 55 5. Rareties ………………….. 60 Cutwork France Paris Office Contact Web 23 rue d’Anjou 6 Avenue René Coty [email protected] cutworkstudio.com 2 / 68 75008 Paris, FR 75014 Paris, FR +31 6 41 17 69 45 instagram: @cutwork Paris | April 2020 The City at a Glance In the past few weeks, a lot of friends have asked me: “what’s this bird I’m seeing / hearing from my window ?” There is a large variety of species that we can watch from our windows. A hovering shape, a backlighted figure, a colorful stroke flying around, a dot in the sky. Ornithologists call that a garden list, or a window list – the list of birds you can spot and recognize without even stepping outside. In cities, nature’s sounds have become merely a background, a white noise. We have tuned out. Not only have we grown used to not hearing; we have stopped listening. Yet, without the car's traffic and the grey sound of our activities, the city is not quiet. It warbles, trills, babbles, chatters, cries, croaks, whistles, hoots, sings… But today, our attention has shifted. Anyone of us will instinctively recognize the shape of a logo, even from far away, or in small print at the bottom of a poster. -

Sweden's Upland Birds

Sweden's Upland Birds Naturetrek Tour Report 3 - 10 June 2016 Red-necked Phalarope on Flatruet high plateau Eurasian Pygmy Ow l Eurasian Dotterel Four Spotted Chaser Report and images by John Willsher Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Sweden's Upland Birds Tour participants: Daniel Green & John Willsher (leaders) with nine Naturetrek clients Summary This trip to central Sweden began with a mid-afternoon arrival at Vasteras in sunshine and 27°C. We were soon out of this small airport and almost immediately in the Black River Valley where we searched the forests and red- barn-dotted farmlands for Owls and Woodpeckers. No time was wasted, and an after dinner foray on our first evening produced Pygmy and Ural Owls, Black and Great Spotted Woodpeckers all accompanied by the sound of Thrush Nightingale, roding Woodcock and Cuckoo. This set the trend, with the good weather continuing as we spent a further day in the valley watching Cranes with young, Whooper Swans on nests, White-tailed Eagles, and finally watching Ural Owl chicks being ringed before we finally headed northwards. Next day in Fulufjallet National Park, a walk through the boreal forest brought us to the highest waterfall in Sweden and a nesting Gyrfalcon. In the north, we saw lekking Great Snipe and on the Flatruet Plateau we watched nesting Dotterel, Golden Plovers, singing Lapland Buntings, confiding Red-necked Phalaropes and a distant Golden Eagle plus, of course, numerous Reindeer. -

Mobbing Behaviour Varies According to Predator Dangerousness And&Nbsp

Animal Behaviour 119 (2016) 119e124 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Mobbing behaviour varies according to predator dangerousness and occurrence * Mylene Dutour , Jean-Paul Lena, Thierry Lengagne Universite de Lyon, UMR5023 Ecologie des Hydrosystemes Naturels et Anthropises, Universite Lyon 1, ENTPE, CNRS, Villeurbanne, France article info Animals possess various antipredator behaviours to reduce their risk of predation. Whereas most prey Article history: make considerable effort to avoid their predators, sometimes individuals approach and mob predators as Received 12 January 2016 a group. Among the types of predators that elicit mobbing, raptors such as hawks and owls are one of the Initial acceptance 18 February 2016 more consistent targets. We conducted playback experiments to investigate the strength of mobbing Final acceptance 2 June 2016 behaviour according to the perceived risk associated with either predator dangerousness or local pre- Available online 25 July 2016 dation pressure. We first determined whether mobbing is specific to dangerous predators or more MS. number: 16-00034R broadly directed at predatory species. We experimentally investigated whether prey can discriminate the level of dangerousness of two owl species. Our results indicate that prey adjusted the strength of their Keywords: mobbing behaviour according to the perceived risk: passerine birds mobbed the Eurasian pygmy owl, antipredator behaviour Glaucidium passerinum (i.e. a dangerous predator) but not the boreal owl, Aegolius funereus (i.e. a far less Eurasian pygmy owl dangerous species). Second, we compared mobbing behaviour in similar habitats differing in predation mobbing behaviour mobbing calls pressure (with or without pygmy owls). -

A Case Study of the Ecology of British Breeding Birds

McKenzie AJ, Robertson PA. Which Species Are We Researching and Why? A Case Study of the Ecology of British Breeding Birds. PLoS ONE 2015, 10(7), e0131004. Copyright: © 2015 McKenzie, Robertson. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. DOI link to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131004 Date deposited: 31/07/2015 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk RESEARCH ARTICLE Which Species Are We Researching and Why? A Case Study of the Ecology of British Breeding Birds Ailsa J. McKenzie1*, Peter A. Robertson1,2 1 Centre for Wildlife Management, School of Biology, Newcastle University, Ridley Building, Claremont Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom, 2 National Wildlife Management Centre, Animal and Plant Health Agency, Sand Hutton, York, United Kingdom * [email protected] Abstract Our ecological knowledge base is extensive, but the motivations for research are many and varied, leading to unequal species representation and coverage. As this evidence is used to support a wide range of conservation, management and policy actions, it is important that OPEN ACCESS gaps and biases are identified and understood. In this paper we detail a method for quantify- ing research effort and impact at the individual species level, and go on to investigate the Citation: McKenzie AJ, Robertson PA (2015) Which Species Are We Researching and Why? A Case factors that best explain between-species differences in outputs. -

HUNGARY & SLOVAKIA Bird Report May 2016 OJ Version

Limosa Holidays Trip Report HUNGARY & SLOVAKIA Hortobágy, Zemplén & Ore Mountains Sat 30 April-Sat 7 May 2016 ___________________________________________________________________________ Trip photos: A female Ural Owl in the Zemplén Hills surveying its territory (top) • female Three-toed Woodpecker on its drumming tree in the Ore Mountains of Slovakia (bottom left) • a male White-backed Woodpecker in its full glory in the Zemplén Hills © Tour leader János Oláh/Limosa Holidays Report compiled by tour leader: János Oláh ___________________________________________________________________________ 1 • © Limosa Holidays, West End Farmhouse, Chapelfield, Stalham Norfolk NR12 9EJ tel: +44 (0)1692 580623 / 4 • email: [email protected] website: www.limosaholidays.co.uk Limosa Trip Report HUNGARY & SLOVAKIA 30 April - 7 May 2016 Hungary & Slovakia | Zemplén, Hortobágy & Ore Mountains Tour Leader: János Oláh with Graeme Charles, Bob Timberlake and Nadine Timberlake This tour is our classic Hungary tour with a little twist – which is a short visit to the Ore Mountains of Slovakia. It was primarily designed to stand a chance of finding all European woodpeckers. The enigmatic Eurasian Three-toed Woodpecker does not live in Hungary but can be seen in the coniferous woodlands of the nearby Ore Mountains. In 2016 we were lucky and we managed to see all 10 species of European woodpeckers! We started our journey in the famous Hortobágy National Park where we experienced full-tilt migration with thousands of breeding-plumaged Ruffs and White-winged Terns moving through. We also had a great selection of special birds here such as the magnificent Great Bustard, Saker Falcon, Red-footed Falcon, Little Crake, Moustached Warbler and River Warbler.