Bio for Website Edit C Hammond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNSUNG: South African Jazz Musicians Under Apartheidunsung

UNSUNG: South African Jazz Musicians under Apartheid outh African jazz under apartheid has in recent years been the subject of numerous studies. The main focus, however, has hitherto been on the musicians who went into exile. Here, for the first time, those who stayed behind are allowed to tell their stories: the stories of musicians from across the colour spectrum who helped to keep their art alive in South Africa during the years of state oppression. CHATRADARI DEVROOP &CHRIS WALTON CHATRADARI Unsung South African Jazz Musicians under Apartheid EDITORS Chatradari Devroop & Chris Walton UNSUNG: South African Jazz Musicians under Apartheid Published by SUN PReSS, an imprint of AFRICAN SUN MeDIA (Pty) Ltd., Stellenbosch 7600 www.africansunmedia.co.za www.sun-e-shop.co.za All rights reserved. Copyright © 2007 Chatradari Devroop & Chris Walton No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic, photographic or mechanical means, including photocopying and recording on record, tape or laser disk, on microfilm, via the Internet, by e-mail, or by any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission by the publisher. First edition 2007 ISBN: 978-1-920109-66-9 e-ISBN: 978-1-920109-67-7 DOI: 10.18820/9781920109677 Set in 11/13 Sylfaen Cover design by Ilse Roelofse Typesetting by SUN MeDIA Stellenbosch SUN PReSS is an imprint of AFRICAN SUN MeDIA (Pty) Ltd. Academic, professional and reference works are published under this imprint in print and electronic format. This publication may be ordered directly from www.sun-e-shop.co.za Printed and bound by ASM/USD, Ryneveld Street, Stellenbosch, 7600. -

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

Faculty of Humanities (Ceremony 3) Contents

FACULTY OF HUMANITIES (CEREMONY 3) CONTENTS Order of Proceedings 2 Mannenberg 3 The National Anthem 4 Distinctions in the Faculty of Humanities 5 Distinguished Teacher Award 6-7 Honorary Degree Recipient 8 Graduands (includes 23 December 2015 qualifiers) 9 Historical Sketch 18 Academic Dress 19-20 Mission Statement of the University of Cape Town 21 Donor Acknowledgements 22 Officers of the University 27 Alumni Welcome 28 1 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES (CEREMONY 3) ORDER OF PROCEEDINGS Academic Procession. (The congregation is requested to stand as the procession enters the hall) The Vice-Chancellor will constitute the congregation. The National Anthem. The University Statement of Dedication will be read by a representative of the SRC. Musical Item. Welcome by the Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Professor DP Visser. Professor Visser will present Dr Azila Talit Reisenberger for the Distinguished Teacher Award. Professor J Hambidge will present Dr Janette Deacon to the Vice-Chancellor for the award of an honorary degree. The graduands will be presented to the Vice-Chancellor by the Dean of Humanities, Professor S Buhlungu. The Vice-Chancellor will congratulate the new graduates. Professor Visser will make closing announcements and invite the congregation to stand. The Vice-Chancellor will dissolve the congregation. The procession, including the new graduates, will leave the hall. (The congregation is requested to remain standing until the procession has left the hall.) 2 MANNENBERG The musical piece for the processional march is Mannenberg, composed by Abdullah Ibrahim. Recorded with Basil ‘Manenberg’ Coetzee, Paul Michaels, Robbie Jansen, Morris Goldberg and Monty Weber, Mannenberg was released in June 1974. The piece was composed against the backdrop of the District Six forced removals. -

DB Music Shop Must Arrive 2 Months Prior to DB Cover Date

05 5 $4.99 DownBeat.com 09281 01493 0 MAY 2010MAY U.K. £3.50 001_COVER.qxd 3/16/10 2:08 PM Page 1 DOWNBEAT MIGUEL ZENÓN // RAMSEY LEWIS & KIRK WHALUM // EVAN PARKER // SUMMER FESTIVAL GUIDE MAY 2010 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:28 AM Page 2 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 3 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 4 May 2010 VOLUME 77 – NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Western Cape Jazz Legends

Western Cape Jazz Legends Foreword The Western Cape Jazz legends which unveiled on 17 March 2011 pays homage to the rich jazz heritage of the Western Cape. The publishing of the Western Cape Jazz Legends Booklet gives a wider audience access to an appreciation of the contribution of these musicians who often plied their trade under the most difficult circumstances and with very little material reward. The short biographies are informed by existing literature and interviews conducted with family members. The list is by no means comprehensive but it does indicate our resolve to give homage, to acknowledge, to preserve and to promote the rich musical heritage of the Western Cape. Documenting our musical history not only ensures that the impact of the role of these legends on the musical landscape of the Western Cape is captured for posterity, but also that their stories serve as a source of inspiration to aspiring musicians. This booklet represents an important step towards the building of a socially inclusive Western Cape. These Jazz Legends united us around our common love for music and the unique sounds of Cape Town Jazz. Let’s celebrate their achievement and resolve that we will continue to build on this initiative to acknowledge our musicians who created musical melodies which filled us with joy, often leaving us in awe of their amazing talent and with a deep sense of self-worth and cultural warmth. Dr IH Meyer Minister of Cultural Affairs and Sport Western cape Government. Western Cape Jazz Legends 1 2 Western Cape Jazz Legends IntroductIon The Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport has embedded in its vision, “… A socially cohesive and creative Western Cape.” The arts and culture component of the department has embraced this vision and the Western Cape Jazz Legends project is reflective thereof. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Faculty of Commerce (Ceremony 5) Contents

FACULTY OF COMMERCE (CEREMONY 5) CONTENTS Order of Proceedings 2 Mannenberg 3 The National Anthem 4 Distinctions in the Faculty of Commerce 5 Distinguished Teacher Award 6-7 Graduands (includes 23 December 2015 qualifiers) 8 Origin of the Bachelor Degree 11 Values of the University 12-13 Academic Dress 14-15 Historical Sketch 16 Mission Statement of the University of Cape Town 17 Donor Acknowledgements 18 Officers of the University 23 Alumni Welcome 24 1 FACULTY OF COMMERCE (CEREMONY 5) ORDER OF PROCEEDINGS Academic Procession. (The congregation is requested to stand as the procession enters the hall) The Acting Vice-Chancellor, Professor DP Visser, will constitute the congregation. The National Anthem. The University Statement of Dedication will be read by a representative of the SRC. Musical Item. Welcome by the Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Professor F Petersen. Professor Petersen will present Jaqui Kew for the Distinguished Teacher Award. Address by Norman Arendse. The graduands and diplomates will be presented to the Acting Vice-Chancellor by the Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Commerce, Professor T Minter. The Acting Vice-Chancellor will congratulate the new graduates and diplomates. Professor Petersen will make closing announcements and invite the congregation to stand. The Acting Vice-Chancellor will dissolve the congregation. The procession, including the new graduates and diplomates, will leave the hall. (The congregation is requested to remain standing until the procession has left the hall.) 2 MANNENBERG The musical piece for the processional march is Mannenberg, composed by Abdullah Ibrahim. Recorded with Basil ‘Manenberg’ Coetzee, Paul Michaels, Robbie Jansen, Morris Goldberg and Monty Weber, Mannenberg was released in June 1974. -

Mannenberg": Notes on the Making of an Icon and Anthem1

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 9, Issue 4 | Fall 2007 "Mannenberg": Notes on the Making of an Icon and Anthem1 JOHN EDWIN MASON Abstract: Abdullah Ibrahim's [Dollar Brand] composition "Mannenberg" was an instant hit, when it was released on the 1974 album, Mannenberg is Where It's Happening. This paper shows that the song is a product of Ibrahim's efforts to find an authentically South African mode of expression within the jazz tradition, blending South African musical forms -- marabi, mbaqanga, and langarm--with American jazz-rock fusion. It quickly became an icon of South African jazz, defining the genre both within the country and overseas. At the same time, the South African coloured community invested the song with their own meaning, transforming it into an an icon of their culture and of themselves. In the 1980s, "Mannenberg" had a second life as an anthem of the struggle against apartheid. Some called it South Africa's "unofficial national anthem." Once again, the song acquired a new meaning, this time through the efforts of musicians, especially Basil Coetzee and Robbie Jansen, who made it the musical centerpiece of countless anti- apartheid rallies and concerts. As the paper traces this narrative, it is constantly aware of the profound influence of African-American culture and political thought on Ibrahim and the coloured community as a whole. Introduction On a winter's day in 1974, a group of musicians led by Abdullah Ibrahim (or Dollar Brand, as most still knew him) entered a recording studio on Bloem Street, in the heart of Cape Town, and emerged, hours later, having changed South African music, forever. -

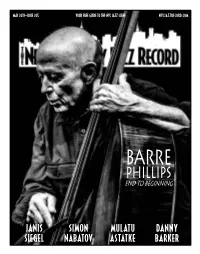

PHILLIPS End to BEGINNING

MAY 2019—ISSUE 205 YOUR FREE guide TO tHe NYC JAZZ sCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BARRE PHILLIPS END TO BEGINNING janis simon mulatu danny siegel nabatov astatke barker Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2019—ISSUE 205 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@nigHt 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : janis siegel 6 by jim motavalli [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist Feature : simon nabatov 7 by john sharpe [email protected] General Inquiries: on The Cover : barre pHillips 8 by andrey henkin [email protected] Advertising: enCore : mulatu astatke 10 by mike cobb [email protected] Calendar: lest we Forget : danny barker 10 by john pietaro [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotligHt : pfMENTUM 11 by robert bush [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or obituaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] Cd reviews 14 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, misCellany 33 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, event Calendar Tom Greenland, George Grella, 34 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Mike Cobb, Pierre Crépon, George Kanzler, Steven Loewy, Franz Matzner, If jazz is inherently, wonderfully, about uncertainty, about where that next note is going to Annie Murnighan, Eric Wendell come from and how it will interact with all that happening around it, the same can be said for a career in jazz. -

Hugh Masekela: the Long Journey 1959-1968

HUGH MASEKELA: THE LONG JOURNEY 1959-1968 By RICARDO CUEVA A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research written under the direction of Dr. Henry Martin and approved by ___________________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2020 © 2020 Ricardo Cueva ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Abstract of the Thesis Hugh Masekela: The Long Journey By Ricardo Cueva Thesis Director: Henry Martin This thesis chronicles Masekela's transition from African refugee to Grammy nominated artist while also encompassing a musical analysis of his work before and including The Promise of the Future. This thesis will provide brief biographical information of Masekela’s life as well as a sociological analysis to give context to his place in US pop culture. This study discusses Masekela’s upbringing in South Africa and explores his transition into 1960s America. This thesis argues that Masekela faced an authenticity complex when breaking into the US market because he defied the expectations of what US audiences thought Africans to be. Masekela overcame this obstacle with the release of The Americanization of Ooga Booga (1966). A musical analysis and critique of the first three albums with an emphasis on Masekela’s breakthrough compositions will be part of this thesis. This thesis concludes with a brief analysis of the cultural and racial impact of Masekela’s work both in the United States and South Africa. ii Acknowledgements I would first and foremost like to thank my parents for their constant support and sacrifice. -

South African Jazz and Exile in the 1960S: Theories, Discourses and Lived Experiences

South African Jazz and Exile in the 1960s: Theories, Discourses and Lived Experiences Stephanie Vos In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Royal Holloway, University of London September 2015 Declaration of Authorship I, Stephanie Vos, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 28 August 2016 2 Abstract This thesis presents an inquiry into the discursive construction of South African exile in jazz practices during the 1960s. Focusing on the decade in which exile coalesced for the first generation of musicians who escaped the strictures of South Africa’s apartheid regime, I argue that a lingering sense of connection (as opposed to rift) produces the contrapuntal awareness that Edward Said ascribes to exile. This thesis therefore advances a relational approach to the study of exile: drawing on archival research, music analysis, ethnography, critical theory and historiography, I suggest how musicians’ sense of exile continuously emerged through a range of discourses that contributed to its meanings and connotations at different points in time. The first two chapters situate South African exile within broader contexts of displacement. I consider how exile built on earlier forms of migration in South Africa through the analyses of three ‘train songs’, and developed in dialogue with the African diaspora through a close reading of Edward Said’s theorization of exile and Avtar Brah’s theorization of diaspora. A case study of the Transcription Centre in London, which hosted the South African exiles Dorothy Masuku, Abdullah Ibrahim, and the Blue Notes in 1965, revisits the connection between exile and politics, broadening it beyond the usual national paradigm of apartheid politics to the international arena of Cold War politics.