War Powers for the 21St Century: the Constitutional Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ronald V. Dellums Fair Chance Access to Housing Ordinance; Adding BMC Chapter 13.106

Page 1 of 37 Office of the Mayor ACTION CALENDAR March 10, 2020 To: Honorable Mayor and Members of the City Council From: Mayor Jesse Arreguín, Councilmembers Cheryl Davila, Kate Harrison, Ben Bartlett Subject: Ronald V. Dellums Fair Chance Access to Housing Ordinance; Adding BMC Chapter 13.106 RECOMMENDATION 1. Adopt a first reading of the Ronald V. Dellums Fair Chance Access to Housing Ordinance, adding Berkeley Municipal Code Chapter 13.106 and; 2. Direct the City Manager to take all necessary steps to implement this chapter including but not limited to developing administrative regulations in consultation with all relevant City Departments including the Rent Stabilization Board, preparing an annual implementation budget, designating hearing officers and other necessary staffing for administrative complaint, exploring the development of a compliance testing program similar to that used by the Seattle Office of Civil Rights, developing timelines and procedures for complaints, conducting outreach and education in partnership with the Alameda County Fair Chance Housing Coalition, and referring program costs to the June budget process. POLICY COMMITTEE RECOMMENDATION On November 7, 2019, the Land Use, Housing, and Economic Development Committee adopted the following action: M/S/C (Droste/Hahn) to move the item with amendments and subject to additional technical revisions with a positive recommendation. Vote: All Ayes. BACKGROUND The City of Berkeley, along with other California urban areas, has seen an unprecedented increase in homelessness, with dire public health and safety consequences. This proposed Fair Chance Housing Ordinance serves as critical strategy to house currently unhoused people and also prevent more people from becoming homeless. -

Washington Update

WASHINGTON UPDATE A MONTHLY NEWSLETTER Vol 5 No 3 Published by the AUSA Institute of Land Warfare March 1993 PRESIDENT CLINTON'S ECONOMIC PLAN, ASPIN'S $10.8 BILLION BUDGET CUT hits the announced Feb. 17, calls for defense spending cuts of Army to the tune of $2.5 billion. The Army reportedly $127 billion in budget authority by 1997 from the pro met the Defense Secretary's Feb. 2 order to cut that posal of former President Bush. Details of just where the amount from a $64.1 billion proposed FY 1994 budget cuts will come must wait until release of the Clinton FY by offering to cancel a number of major weapons now in 1994 Defense budget-expected around the end of production or development and by accelerating the draw March. All that is known to date is that the President down of troops from Europe. How many of these will plans a 1.4 million active-duty force (vice Bush's 1.6 make it through the budget process is pure speculation at million); cuts the U.S. force in Europe to about 100,000, this point. The specific reductions won't be known until (Bush projected 150,000); freezes the SDI program at President Clinton sends his FY 1994 budget to Capitol $3.8 billion a year, (Bush saw $6.3 billion request for FY Hill (expected late March), but "Pentagon officials" have 1994 alone); and imposes a freeze on federal pay in commented in the media that the Army proposes to cut: creases in 1994 and limited raises thereafter. -

Senate WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 15, 2018

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 15, 2018 No. 135 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Friday, August 17, 2018, at 9 a.m. Senate WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 15, 2018 The Senate met at 12 noon and was The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without spend the summer in Syria as a free- called to order by the President pro objection, it is so ordered. lance journalist. He was frustrated tempore (Mr. HATCH). f with the lack of good information on f Syria’s civil war—a war that, by some RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME estimates, has claimed more than one- PRAYER The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under half million lives and displaced mil- The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- the previous order, the leadership time lions more, having created a refugee fered the following prayer: is reserved. crisis affecting neighboring countries, Let us pray. like Jordan, Turkey, and Lebanon, and Glorious God, the source of our f having destabilized the entire region. strength, fill us with life anew. CONCLUSION OF MORNING In spite of the violence and political Strengthen and guide our lawmakers BUSINESS by the light of Your counsels, directing turmoil and as a strong believer in the their steps. Lord, open their eyes so The PRESIDING OFFICER. Morning freedom of the press, Austin wanted to that they may discern Your truth and business is closed. let his fellow Americans know what courageously obey Your precepts. -

Rep. Bass Elected to Chair House Subcommittee on Africa, Global

Rep. Bass Elected To Chair House Subcommittee On Africa, Global Jan Perry Declares Candidacy Health, Global Human Rights and for Los Angeles County Supervi- International Organizations sor (See page A-2) (See page A-14) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBER 12 - 18, 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO. 05, $1.00 +CA. Sales “ForTax Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years TheYears Voice The Voiceof Our of Community Our Community Speaking Speaking for forItself Itself” THURSDAY, JANUARY 31, 2019 BY NIELE ANDERSON Staff Writer James Ingram’s musi- cal career will forever be carved in the Grammy ar- chives and Billboard 100 charts. His rich and soulful vocals ruled the R&B and Pop charts in the 80’s and 90’s. Ingram was discov- ered by Quincy Jones on a demo for the hit, Just Once, written by Barry Mann and FILE PHOTO Cynthia Weil, which he sang for $50. STAFF REPORT investigation regarding He went on to record the Los Angeles Police hits, “Just Once,” “One Long before the 2015 Department’s Metropoli- Hundred Ways,” “How Sandra Bland traffic stop tan Division and the in- Do You Keep the Music in Houston, Texas, Afri- creasing number of stops Playing?” and “Yah Mo can Americans have been officers have made on Af- B There,” a duet with Mi- battling with the reoccur- rican American motorists. chael McDonald. One of ring fear of driving while According to the re- his milestone writing cred- Black. Some people be- port, “Nearly half the driv- its was with Quincy Jones lieve that the fear of driv- ers stopped by Metro are on Michael Jackson’s 1983 ing while Black, is associ- Black, which has helped Top 10 hit “P.Y.T.” (Pretty ated with a combination drive up the share of Afri- Young Thing). -

Hearing National Defense Authorization Act For

i [H.A.S.C. No. 110–133] HEARING ON NATIONAL DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION ACT FOR FISCAL YEAR 2009 AND OVERSIGHT OF PREVIOUSLY AUTHORIZED PROGRAMS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION FULL COMMITTEE HEARING ON BUDGET REQUEST FROM THE U.S. PACIFIC COMMAND AND U.S. FORCES KOREA HEARING HELD MARCH 12, 2008 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 45–824 WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 HOUSE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS IKE SKELTON, Missouri, Chairman JOHN SPRATT, South Carolina DUNCAN HUNTER, California SOLOMON P. ORTIZ, Texas JIM SAXTON, New Jersey GENE TAYLOR, Mississippi JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York NEIL ABERCROMBIE, Hawaii TERRY EVERETT, Alabama SILVESTRE REYES, Texas ROSCOE G. BARTLETT, Maryland VIC SNYDER, Arkansas HOWARD P. ‘‘BUCK’’ MCKEON, California ADAM SMITH, Washington MAC THORNBERRY, Texas LORETTA SANCHEZ, California WALTER B. JONES, North Carolina MIKE MCINTYRE, North Carolina ROBIN HAYES, North Carolina ELLEN O. TAUSCHER, California W. TODD AKIN, Missouri ROBERT A. BRADY, Pennsylvania J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia ROBERT ANDREWS, New Jersey JEFF MILLER, Florida SUSAN A. DAVIS, California JOE WILSON, South Carolina RICK LARSEN, Washington FRANK A. LOBIONDO, New Jersey JIM COOPER, Tennessee TOM COLE, Oklahoma JIM MARSHALL, Georgia ROB BISHOP, Utah MADELEINE Z. BORDALLO, Guam MICHAEL TURNER, Ohio MARK E. UDALL, Colorado JOHN KLINE, Minnesota DAN BOREN, Oklahoma PHIL GINGREY, Georgia BRAD ELLSWORTH, Indiana MIKE ROGERS, Alabama NANCY BOYDA, Kansas TRENT FRANKS, Arizona PATRICK J. -

Now Or Never

PUBLISHED BY THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALISTS OF AMERICA September/October 1995 Volume XXIII Number 5 $1.50 Now or Never Labor Day 1995 Inside Democratic Left Editorial: Ron Dellurns on economic Ron Aronson: 3 insecurity and the rise of the right 2 5 Socialism Without Apologies Perestroika on Sixteenth Street: Daraka Larimore-Hall: 4 Harold Meyerson on the AFL-CIO 3O A Letter from Zagreb Joel Shufro on Republican attacks on workplace safety 10 38 DSAction Power Across Borders: 14 Ginny Coughlin on the past and 0n the Left future of international organizing 40 by Harry Fleischman Jos~ Zu~kerbe~g on independent 19 umons m Mexico 42 Dear Margie The Left Bookshelf: Jo-Ann Mort Present Progressive 24 reviews Lia Matera' s Designer Crimes 4 3 by Alan Charney cover photo· David Bacon/Impact Vuuab DE~10CRATIC LEFT Final Notice: National Director Alan Charney }vfo11agi11g Editor The 1995 DSA National tonvention David Glenn Editorial Committee November 10 - 12 •Washington, D.C. Joanne Barkan, Dorothee Benz, Everyone is welcome--but in order to make this year's Com·en Suzanne Crowell, Jeff Gold, Sherri Le\'ine, tion as inexpensive as possible, we've had to set an early deadline Steve Max, Maxine Phillips for registration. So ifyou're interested in attending, contact DSA f qzmding Editor Program Coordinator Michele Rossi immediatery at 2121727- Michael Harrington 8610 or [email protected]. (1928-1989) !P111DlTt1tlc Left (ISSNOl6400~07) is publish<'d If you'd like to submit resolutions to be considered at the bimonUlly at 180VarldcStsttt. New York. NY 10014. Sccond-da.M pcx'.age pid at :>:cw York. -

23716 Hon. Anna G. Eshoo Hon. Ike Skelton Hon. Barbara Lee Hon. Fortney Pete Stark

23716 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS October 19, 2000 Paladin is just one of the many high-tech, Mr. Dellums was first elected to the U.S. In fact, greater spending does not always bio-tech, and information technology busi- House of Representatives in 1970, serving guarantee better quality. nesses that are stimulating economic growth until his retirement in 1998, Mr. Dellums was I would like to call my colleagues’ attention and creating new jobs in our country. Like a distinguished and respected leader in the to a recent report published in the Journal of many other Members of Congress, I value the Congress and throughout the world and re- the American Medical Association (JAMA) en- contributions of our dynamic high-tech industry mains a tireless leader on behalf of peace and titled, ‘‘Quality of Medical Care Delivered to and want to make sure that the government justice. Medicare Beneficiaries: A Profile at State and continues to take appropriate action to help His diverse accomplishments include his National Levels.’’ This report, compiled by re- stimulate and develop this industry. I invite leadership and vision as the Chair of the Con- searchers at the Health Care Financing Ad- other Members of Congress to join me in con- gressional Black Caucus, Chair of the House ministration, ranks states according to percent- gratulating Paladin Data Systems for their Armed Services and District of Columbia Com- age of Medicare Free-for-Service beneficiaries amazing success and wishing them nothing mittees; his challenge against the Vietnam receiving appropriate care. The researchers but the best in years to come. -

Congressional Record—House H676

H676 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE February 23, 1999 It is most fitting and proper that we support man Dellums championed issues in- I am honored to have carried this leg- this legislation and honor the civic career of volving civil rights, equal rights for islation. Again, I want to thank the Richard C. White by designating the federal women, human rights, and the environ- committee so much for taking the time building in El Paso as the ``Richard C. White'' ment. and the effort to get this to the floor in Federal Building. At the time of his resignation, Con- such a timely fashion. Mr. Speaker, I yield back the balance gressman Dellums was the ranking Mr. WISE. Mr. Speaker, I yield my- of my time. member on the House Committee on self such time as I may consume. The SPEAKER pro tempore (Mr. National Security. During his tenure, Mr. Speaker, I rise in strong support PEASE). The question is on the motion he also held the chairmanship of the of H.R. 396, a bill to honor Ron Dellums offered by the gentleman from New Committee on Armed Services and the by naming the Federal building located Jersey (Mr. FRANKS) that the House Committee on the District of Colum- at 1301 Clay Street in Oakland, Califor- suspend the rules and pass the bill, bia. Throughout his 27-year career, nia, as the ``Ronald V. Dellums Federal H.R. 233. Congressman Dellums served on a vari- Building.'' The question was taken; and (two- ety of other committees and caucuses, As my colleagues know, Ron rep- thirds having voted in favor thereof) including the Committee on Foreign resented the 9th District of California the rules were suspended and the bill Affairs, the Committee on the Post Of- for 26 years and during that period dis- was passed. -

December 1992

1 VOL. 50, NO 12 OPERATING ENGINEERS LOCAL UNION NO. 3, SAN FRANCISCO, CA DECEMBER 1992 a a 9·r-t 0. 0 - . il 0 i .. I I f L Semi=Annual Meeting 1 Notice, see page 18 1 - ~=- ON 7 1 i Photo by Steve Moler 1 2 DECEMBER 1992/ Engineers News 2 -3 G--0-3 SZ *,1 - - , , , , Dave Briggs (left) m'* i :,5 ,&*idlll I:,; .2, .;: · 48, 0 6 * 91:liti, 21014 f ~:id- :* jt :-'1ag.. w ·1 1#bt* trains an appren- - - Welfare .. =T/6. tice while working A.' A -, -- , ., :-» -. 4*U 1 -4 1 4 3'8: =.. 11:./tlt as a welding in- '4 ,%2 1 7/4'*> 4.1 structor at Rancho 4 , tellIi. i.i ..3.1./.,; 1 1, . We've all heard a million "good news, bad news" . 1.4'. - , .- 5 Jil '.: fit Murieta Training jokes in our lifetime. I've got one, but it isn't a joke. -4:' V ,;. ''t-3. 4*:1£ 4.. 1 - Center in the late The good news is, economists are predicting that the ..:*, * v d" - 4. 1970s. country seems to be showing signs of recovery. The 9 i bad news is, California isn't getting any of it. They ~ .*.+* + 2.- * say the Golden State may continue to slide for at I. & r ...F . : I =.* 4 4 least another year. , t:;= , f ..]6-;&i{ .. .. Here's another one. 1 34= *4 :· r . , The good news is, Bill .. - ri . Clinton will soon be run- Good news, ' 4 + ning the country. The bad news is, Pete Wilson *T,#~..1 'v . -

Container 108 to Se

2/28/79 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 2/28/79; Container 108 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf :•, . '>l "'" &,. '\., ., �" ·!:. a/' . " >' .. .,..· ·4!. i,, ,0 • . , ,., J�'' ,o . •" ., ' �. ; ' / ' ' .. ;� ' · ,..,,!'".' ..... , ,, f · ' " 4� . ' . .. "' . 0 of • , , . .; ,,1 '· .:'<- ' �. '" � .• ·, -.�,) � i) ll '· .,, '' . ', ftl '\1 {'' 0 ,, . � . , . c (l "� ,· ·· '· ; FILE LOCATION , .. Presidentdal Papers.: Staff' carter " � Offices,.j ' . 2/28/79. oox, 12r · . ,, < RESTRICTION CODES · . .• ·� •.'Jf � ; � ;� �� � , . ..O: ,, · , , (i) �Ciosed by Ex ·utive Order 1,2356'govern ng ac� ss·to natio l secu"H i t rm tion . 6 � ; . ., ' ' ·.�' •. ;::.:�. ;•. • }Ciosed'by statute or PY the agency which originated the dqc,umer:lt. ' • ::· (� •.• t,., ' • ' .t'• 'll· i ,'· ·�·'',;:f'((B) j' 'Cio n a o t t i i n t �;? n the onor � g ·<" , .;}'. C sed l cc r�an7E! vyi h'r� � ct o s co� �� i , d 's eed·:�t· !ft. ' :,;�:;:. '}:;. · ., ., , '; . , .� ��:.� �· : ., -�' , .· . ''' , "'" •J., . �".,11,�· . · . '- ' • . ��·�:·_ �'1 ' ., 'W• " �-·<t>:p•r',�o n,"' 11 'l. ,u<;jU\> 1' · .-; .·. ""a· ij ,,f J' :¢'-'1<� , . 'a··�- l' �... • •· � .. � 11 · , .•· ..o(t' · ,1· : RECORDS: :Ab:M,If:liSTR,AyiO'N.' ••'' . ,, NA.,F. R AND, ' . 1'";�i 4t'� ' 0 -��J;.-O �·. '• . ; ·,, ··;·.. ·.' if.i. ��::.:,. .�"t .J,, · .:'.NATiONAL· ARCHWES·• 1429 (6;_�85)'�:,·.�:�.-. ... ,' .�;: ' )".;.'�. �·, � ;�.'.. .. :_�::, .:·.·:��;. .. . -

Special Election Dates

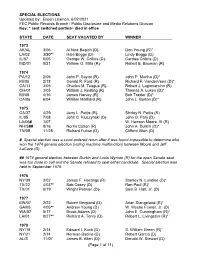

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

Congressional Record—House H9811

August 1, 1996 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE H9811 we are all anxious to complete our Mr. SOLOMON. Mr. Speaker, as I un- gust recess tomorrow. Further, the re- work to make our departures for our derstand it, the next item of business port has been available in committee August recess work period. will be the rule on the defense author- offices so Members and staff have had At this time I can only advise Mem- ization conference report. It is my in- ample time to review it. bers, to the best of my knowledge, we tention to only use 2 or 3 minutes and Mr. Speaker, this is a fair rule that should expect additional votes this then, when the manager on the Demo- provides for expeditious consideration evening within the hour. At any point crat side has done the same, we would of this critically important legislation. during the evening, when I find infor- then yield back our time and expedite I urge support of the rule. I will not mation by which I can advise other- this rule without a vote. bother to get into the details of the wise, I will ask for time to do so. But Mr. FROST. Mr. Speaker, will the bill. It has been debated at consider- my best advice at this point is we must gentleman yield? able length. We all know the contents. be prepared to stay for additional votes Mr. SOLOMON. I yield to the gen- Mr. Speaker, I urge prompt action on tonight, and I will keep Members in- tleman from Texas.