Chi Omega History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Standard

IEC 62106 ® Edition 2.0 2009-07 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD Specification of the Radio Data System (RDS) for VHF/FM sound broadcasting in the frequency range from 87,5 MHz to 108,0 MHz --`,,```,,,,````-`-`,,`,,`,`,,`--- IEC 62106:2009(E) Copyright International Electrotechnical Commission Provided by IHS under license with IEC No reproduction or networking permitted without license from IHS Not for Resale THIS PUBLICATION IS COPYRIGHT PROTECTED Copyright © 2009 IEC, Geneva, Switzerland All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from either IEC or IEC's member National Committee in the country of the requester. If you have any questions about IEC copyright or have an enquiry about obtaining additional rights to this publication, please contact the address below or your local IEC member National Committee for further information. IEC Central Office 3, rue de Varembé CH-1211 Geneva 20 Switzerland Email: [email protected] Web: www.iec.ch About the IEC The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is the leading global organization that prepares and publishes International Standards for all electrical, electronic and related technologies. About IEC publications The technical content of IEC publications is kept under constant review by the IEC. Please make sure that you have the latest edition, a corrigenda or an amendment might have been published. Catalogue of IEC publications: www.iec.ch/searchpub The IEC on-line Catalogue enables you to search by a variety of criteria (reference number, text, technical committee,…). -

ALPHA CHI OMEGA Accreditation Report 2014-2015

ALPHA CHI OMEGA Accreditation Report 2014-2015 Intellectual Development Alpha Chi Omega was ranked second out of nine Panhellenic Sororities in the fall 2014 semester with a GPA of 3.4475, a decrease of .01306 from the spring 2014 semester. The 3.4475 GPA placed the chapter above the All Sorority and All Greek average. Alpha Chi Omega was ranked first out of nine Panhellenic Sororities in the spring 2015 semester with a GPA of 3.48402, an increase of .03652 from the fall 2014 semester. The 3.48402 GPA placed the chapter above the All Sorority and All Greek average. Alpha Chi Omega’s spring 2015 new member class GPA was 3.383, ranking first out of nine Panhellenic Sororities. Alpha Chi Omega had 46.6% of the chapter on the Dean’s List in the fall 2014 semester and 28.2% on the Dean’s List in the spring 2015 semester. Alpha Chi Omega requires a minimum 2.6 GPA for membership. This standard is higher than the Inter/National Headquarters and University requirements. Alpha Chi Omega fosters an environment for strong academic performance. The chapter provides in-house tutoring, peer mentoring, and regular study hours. The chapter also connects members to the Center for Academic Success, the Writing and Math Center, and other on-campus resources. Alpha Chi Omega maintains a designated study space frequently used by members as well as tutors, teaching assistants, and professors leading study sessions. This space is complete with a study buddy desk fully stocked with office and study supplies. Alpha Chi Omega’s academic plan—incorporating individualization and positive incentives—is consistently recognized as a best practice. -

Cost Comparison| Projected 2019-2020

Cost Comparison | Projected 2019-2020 Panhellenic Sorority Financial Informa tion | University of Nebraska-Lincoln Average New Member Cost $2,020 | Live-In 7,371 l Live-out 1.807 ALPHA XI DELTA | House Capacity 72 ALPHA CHI OMEGA | House Capacity 62 New Member $1,880 | Live-in $6,700 l Live-out $1,430 New Member Cost Includes: New member fee, initiation fee, badge New Member $2,455 | Live-in $7,210 l Live-out $2,060 New Member Cost Includes: Facility operation dues, national dues, fee, chapter dues, national dues and house improvement fee. Live-in Cost Includes: All live-out costs plus a meal plan and room new member dues, meal plan, badge fee. Live-in Cost Includes: Room and board, facility operation dues, rent. Live-out Cost Includes: Chapter dues, national dues and house national dues, meal plan, chapter dues. Live-out Cost Includes: Facility operation dues, national dues, meal improvement fee. Payment Methods | OmegaFi - Direct eCheck or Credit/Debit card plan, chapter dues. Payment Methods | Billhighway Payment Plan | Monthly or Case-by-case Basis Payment Plan | Monthly or Semester CHI OMEGA | House Capacity 72 New Member $1,565 | Live-in $7,940 l Live-out $1,870 ALPHA DELTA PI | House Capacity 62 New Member Cost Includes: Chapter dues, new member fee, New Member $3,631 | Live-in $11,484 l Live-out $3,484 national insurance, Panhellenic dues, house corporation and initiation New Member Cost Includes: Chapter dues, initiation fee, badge fee. fee, administration fee. Live-in Cost Includes: Local and national dues, insurance fee, room Live-in Cost Includes: Rent, chapter dues, building fund fee. -

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

2019 Order of Omega Greek Awards

2019 Year Order of Omega Greek Awards Ceremony President’s Cup: PHC Chi Omega President’s Cup: IFC Sigma Phi Epsilon President’s Cup: NPHC Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. Outstanding Social Media: IFC Alpha Tau Omega Outstanding Social Media: PHC Chi Omega Outstanding Social Media: NPHC Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. Outstanding Philanthropic Event: PHC 15k in a Day (Delta Delta Delta) Outstanding Philanthropic Event: IFC Paul Cressy Crawfish Boil (ΚΣ, ΚΑ, ΣΑΕ) Outstanding Philanthropic Event: NPHC Who’s Trying To Get Close (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Philanthropist: PHC Eleanor Koonce (Pi Beta Phi) Outstanding Philanthropist: NPHC Lauren Bagneris (Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc.) Outstanding Philanthropist: IFC Gray Cressy (Kappa Alpha Order) Outstanding Chapter Event: PHC Confidence Day (Kappa Delta) Outstanding Chapter Event: IFC Alumni Networking Event (Sigma Phi Epsilon) Outstanding Chapter Event: NPHC Scholarship Pageant (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Sisterhood: PHC Alpha Delta Pi Outstanding Brotherhood: IFC Sigma Nu Outstanding Brotherhood: NPHC Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. Outstanding New Member: PHC Ellie Santa Cruz (Delta Zeta) Outstanding New Member: IFC Rahul Wahi (Alpha Tau Omega) Outstanding New Member: NPHC Sam Rhodes (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Chapter Advisor: PHC Kathy Davis (Delta Delta Delta) Outstanding Chapter Advisor: IFC Jay Montalbano (Kappa Alpha Order) Outstanding Chapter Advisor: NPHC John Lewis (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Sorority House -

Sorority Financial Information

jhjkhjk UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT SORORITY FINANCIAL INFORMATION ALPHA DELTA PI DELTA DELTA DELTA NEW MEMBER FEE BREAKDOWN PER SEMESTER NEW MEMBER FEE BREAKDOWN PER SEMESTER Inter/National Fee $97.50 Badge Fee $175.00 Badge Fee $165.00 Parlor Fee $140.00 House Fee $50.00 Chapter Dues $560.00 Dues $350.00 Capital Improvement Fee $50.00 Initation Fee $140.50 New Member Fee to Fraternity $47.50 OmegaFi Fee $28.75 New Member Fee to House Corporation $10.00 TOTAL Active Member Fee Breakdown $831.75 Initiation Fee to Fraternity $160.00 ACTIVE MEMBER FEE BREAKDOWN PER SEMSTER Initiation Fee to House Corporation $20.00 OUT OF HOUSE TOTAL Out of House $1,162.50 Inter/National Fee (fall semester only) $110.50 ACTIVE MEMBER FEE BREAKDOWN PER SEMESTER Parlor Fee $50.00 OUT OF HOUSE Dues $475.00 Parlor Fee $140.00 OmegaFi Fee $28.75 Chapter Dues $560.00 Building Fee $100.00 Capital Improvement Fee $50.00 TOTAL (Fall Semster) $764.25 TOTAL $750.00 TOTAL (Spring Semster) $653.75 IN HOUSE IN HOUSE (DOES NOT INCLUDE HOUSE RENT/EXPENSES) Meal Plan $1,900.00 Inter/National Fee (fall semester only) $110.50 Chapter Dues $560.00 Dues $475.00 Capital Improvement Fee $50.00 OmegaFi Fee $28.75 Resident Fee $3,200.00 Building Fee $100.00 Room and Key Deposit $100.00 TOTAL (Fall Semster) $714.25 TOTAL $5,810.00 TOTAL (Spring Semster) $603.75 *In House Resdiency Requirement: All 16 spots must be filled *In House Resdiency Requirement: Executive Board Members* ALPHA CHI OMEGA KAPPA DELTA NEW MEMBER FEE BREAKDOWN PER SEMESTER NEW MEMBER FEE BREAKDOWN PER SEMESTER National -

The Use of Gamma in Place of Digamma in Ancient Greek

Mnemosyne (2020) 1-22 brill.com/mnem The Use of Gamma in Place of Digamma in Ancient Greek Francesco Camagni University of Manchester, UK [email protected] Received August 2019 | Accepted March 2020 Abstract Originally, Ancient Greek employed the letter digamma ( ϝ) to represent the /w/ sound. Over time, this sound disappeared, alongside the digamma that denoted it. However, to transcribe those archaic, dialectal, or foreign words that still retained this sound, lexicographers employed other letters, whose sound was close enough to /w/. Among these, there is the letter gamma (γ), attested mostly but not only in the Lexicon of Hesychius. Given what we know about the sound of gamma, it is difficult to explain this use. The most straightforward hypothesis suggests that the scribes who copied these words misread the capital digamma (Ϝ) as gamma (Γ). Presenting new and old evidence of gamma used to denote digamma in Ancient Greek literary and documen- tary papyri, lexicography, and medieval manuscripts, this paper refutes this hypoth- esis, and demonstrates that a peculiar evolution in the pronunciation of gamma in Post-Classical Greek triggered a systematic use of this letter to denote the sound once represented by the digamma. Keywords Ancient Greek language – gamma – digamma – Greek phonetics – Hesychius – lexicography © Francesco Camagni, 2020 | doi:10.1163/1568525X-bja10018 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. from Brill.com09/30/2021 01:54:17PM via free access 2 Camagni 1 Introduction It is well known that many ancient Greek dialects preserved the /w/ sound into the historical period, contrary to Attic-Ionic and Koine Greek. -

Timeline of Fraternities and Sororities at Texas Tech

Timeline of Fraternities and Sororities at Texas Tech 1923 • On February 10th, Texas Technological College was founded. 1924 • On June 27th, the Board of Directors voted not to allow Greek-lettered organizations on campus. 1925 • Texas Technological College opened its doors. The college consisted of six buildings, and 914 students enrolled. 1926 • Las Chaparritas was the first women’s club on campus and functioned to unite girls of a common interest through association and engaging in social activities. • Sans Souci – another women’s social club – was founded. 1927 • The first master’s degree was offered at Texas Technological College. 1928 • On November 21st, the College Club was founded. 1929 • The Centaur Club was founded and was the first Men’s social club on the campus whose members were all college students. • In October, The Silver Key Fraternity was organized. • In October, the Wranglers fraternity was founded. 1930 • The “Matador Song” was adopted as the school song. • Student organizations had risen to 54 in number – about 1 for every 37 students. o There were three categories of student organizations: . Devoted to academic pursuits, and/or achievements, and career development • Ex. Aggie Club, Pre-Med, and Engineering Club . Special interest organizations • Ex. Debate Club and the East Texas Club . Social Clubs • Las Camaradas was organized. • In the spring, Las Vivarachas club was organized. • On March 2nd, DFD was founded at Texas Technological College. It was the only social organization on the campus with a name and meaning known only to its members. • On March 3rd, The Inter-Club Council was founded, which ultimately divided into the Men’s Inter-Club Council and the Women’s Inter-Club Council. -

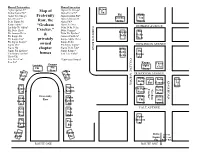

Map of Fraternity Row, the “Graham Cracker,”

Housed Fraternities: Housed Sororities Alpha Epsilon Pi* Map of Alpha Chi Omega* Sigma Alpha Sigma Phi* Alpha Delta Pi* Nu Phi Alpha Alpha Tau Omega Fraternity Alpha Epsilon Phi* Beta Theta Pi* Alpha Omicron Pi Gamma Tau Delta Sigma Phi Row, the Alpha Phi* Delta Omega Kappa Alpha* Alpha Xi Delta “Graham ROAD NORWICH Lambda Chi Alpha* Delta Delta Delta HOPKINS AVENUE Phi Delta Theta Cracker,” Delta Gamma* Kappa Phi Phi Gamma Delta & Delta Phi Epsilon* Delta Phi Kappa Psi Gamma Phi Beta* Delta Theta Phi Kappa Tau* privately Kappa Alpha Theta Phi Sigma Kappa* Kappa Delta Sigma Chi* owned Phi Sigma Sigma* DICKINSON AVENUE Sigma Nu chapter Sigma Delta Tau* Delta Sigma Phi Epsilon* Sigma Kappa * Delta Phi Tau Kappa Epsilon* houses Zeta Tau Alpha* Kappa Theta Chi Delta COLLEGE AVENUE COLLEGE Psi Zeta Beta Tau* *University Owned Zeta Psi* Kappa Theta Lambda Gamma Alpha Chi Chi Phi Theta Alpha Beta Alpha Beta PRINCETON AVENUE Theta Sigma Phi Alpha Alpha Delta Alpha Pi ROAD KNOX Delta Phi Gamma Xi Pi Phi Sigma Delta “Graham “Graham Sigma Phi Sigma Cracker” Kappa Delta Tau Kappa Sigma Tau Fraternity Alpha Alpha Delta Alpha Row Epsilon Chi Phi Epsilon Omega Pi Phi Epsilon Zeta Zeta YALE AVENUE Beta Tau Tau Alpha Alpha Phi Zeta Omicron Sigma Pi Psi Kappa Kappa Sigma Delta (across Alpha Chi Sigma Rt. 1 on Phi Knox Rd) ROUTE ONE ROUTE ONE . -

Implementing Cross-Locale CJKV Code Conversion

Implementing Cross-Locale CJKV Code Conversion Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/ujip/unicode/iuc13-c2-paper.pdf ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/ujip/unicode/iuc13-c2-slides.pdf Code Conversion Basics dc • Algorithmic code conversion — Within a single locale: Shift-JIS, EUC-JP, and ISO-2022-JP — A purely mathematical process • Table-driven code conversion — Required across locales: Chinese ↔ Japanese — Required when dealing with Unicode — Mapping tables are required — Can sometimes be faster than algorithmic code conversion— depends on the implementation September 10, 1998 Copyright © 1998 Adobe Systems Incorporated Code Conversion Basics (Cont’d) dc • CJKV character set differences — Different number of characters — Different ordering of characters — Different characters September 10, 1998 Copyright © 1998 Adobe Systems Incorporated Character Sets Versus Encodings dc • Common CJKV character set standards — China: GB 1988-89, GB 2312-80; GB 1988-89, GBK — Taiwan: ASCII, Big Five; CNS 5205-1989, CNS 11643-1992 — Hong Kong: ASCII, Big Five with Hong Kong extension — Japan: JIS X 0201-1997, JIS X 0208:1997, JIS X 0212-1990 — South Korea: KS X 1003:1993, KS X 1001:1992, KS X 1002:1991 — North Korea: ASCII (?), KPS 9566-97 — Vietnam: TCVN 5712:1993, TCVN 5773:1993, TCVN 6056:1995 • Common CJKV encodings — Locale-independent: EUC-*, ISO-2022-* — Locale-specific: GBK, Big Five, Big Five Plus, Shift-JIS, Johab, Unified Hangul Code — Other: UCS-2, UCS-4, UTF-7, UTF-8, -

National Honor and Recognition 1

National Honor and Recognition 1 National Honor and Recognition • National Honor Societies (p. 1) • National Recognition Societies (p. 1) National Honor Societies The following members of the Association of College Honor Societies have established chapters at Auburn: Alpha Delta Mu (Social Work), Alpha Epsilon (Biosystems Engineering), Alpha Epsilon Delta (Pre-Medicine), Alpha Kappa Delta (Sociology), Alpha Lambda Delta (Freshman Scholarship), Alpha Phi Sigma (Criminal Justice), Alpha Pi Mu (Industrial Engineering), Alpha Sigma Mu (Metallurgical & Materials Engineering), Beta Alpha Psi (Accounting), Beta Gamma Sigma (Business), Cardinal Key (Junior Leadership), Chi Epsilon (Civil Engineering), Eta Kappa Nu (Electrical and Computer Engineering), Kappa Delta Pi (Education), Iota Delta Sigma (Counselor Education), Lambda Sigma (Sophomore Leadership), Mortar Board (Student Leadership), Omega Chi Epsilon (Chemical Engineering), Omicron Delta Kappa (Student Leadership), Kappa Omicron Nu (Human Sciences), Phi Alpha Theta (History), Phi Beta Kappa (Arts and Sciences), Phi Eta Sigma (Freshman Scholarship), Phi Kappa Phi (Senior Scholarship), Phi Lambda Sigma (Pharmacy Leadership), Phi Sigma Tau (Philosophy), Pi Delta Phi (French), Pi Lambda Sigma (Pre-Law), Pi Sigma Alpha (Political Science), Pi Tau Sigma (Mechanical Engineering), Psi Chi (Psychology), Rho Chi (Pharmacy), Sigma Delta Pi (Spanish), Sigma Gamma Tau (Aerospace Engineering), Sigma Pi Sigma (Physics), Sigma Tau Delta (English), Tau Beta Pi (Engineering), Tau Sigma Delta (Architecture -

Pearlessence

ZETA OMICRON Pearl Essence OMEGA Pearl Essence Edition 111 1st Quarter 2011 Greetings from the Basileus Dear Sorors, I want to thank you for making my first year as Basileus a very pleasant one. You all worked very hard to implement the projects, programs, and events that were outlined at the beginning of the year. We set a lot of goals last January and you all worked very hard to see them come to fruition. Our theme for this year is, “We’ve Only Just Begun.” When I first began thinking about it, I was thinking in terms of us being halfway through my tenure as Basileus. I was hoping to use this theme as our through my tenure as Basileus. I was hoping to use this theme as our mantra to push forward toward the end of my term in office. However, the more I t hink about it, the more I feel that we should internalize it in ou r day-to- day walk as Sorors. Whether this is your second year as a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. or you are a life-member, I want you to take it to heart. “We’ve Only Just Begun.” Go back to that same spirit and mindset you had on the day you first got your that same spirit and mindset you had on the day you first got your pearls. “We’ve Only Just Begun.” Meditate on the thrill and the excitement you felt the first time you attended your first Cluster, Regional, and Boule. “We’ve Only Just Begun.” Think about the first time you sang the National hymn with your Sorors.