Alpha Delta Pi History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 1 2012

Jamie Bero, Clarion (PA)- E0 1988, is proud to be a Delta Zeta. A member of Clarion Fire and Hose Company #1 in Clarion, Pennsylvania, she is the College Chapter Director (CCD) of the Delta Upsilon Chapter at Marshall University, Director Student Affairs at the University of Charleston School of Pharmacy and Head Cheer Coach at the University of Charleston. Jamie was the CCD for the Epsilon Theta Chapter at Clarion University and a member of the Clarion County Emergency Response Team when the photo was taken. She says, Issue 1 - 2012 "The educational aspects of firefighting have always been my favorite. Sometimes the Volume 100, No.1 little ones look up and say, 'Is that fireman a girl?'" In this issue I am a Delta Zeta! ............................................................... .. ... 4 Flame Eternal .......... .. ..................... ..................................... 17 Delta Zeta enriches for a lifetime Recruitment and Legacy Introduction Form........................ 18 I am a Delta Zeta ... I belong ................................................... 7 Guest columnist Jane Carter Handly, 2007 Woman of the Year Alumnae News .................................................................... 20 On Campus ................. :. ........................................................... 9 Membership, Recognition and Sisterhood ........................... 22 Delta Zeta Foundation .... ........................................................ 16 Alumnae and Collegiate Profiles .......................................... 24 Endowments are key to Delta Zeta's future Delta Zeta's JobBound Resources Give Alumnae an Edge ....... 28 Please visit http://www.deltazeta.org/ and go to About Delta Zeta > Publications to read the latest issue. If you would like ro read The LAMP online to help the Sorority to go green, please email us at [email protected]. You will receive an email alert when the next issue is online. If you wanr to conrinue to receive 1l1e LAMP in its hard copy format, mailed to you three times a year, you need not do anything. -

Sorority/Fraternity Information – Fall 2017 (As of 1/19/2018)

Sorority/Fraternity Information – Fall 2017 (as of 1/19/2018) Chapter # Members Chapter GPA Rank Alpha Chi Omega 90 3.449 6 Alpha Kappa Alpha 16 3.26 13 Chi Omega 110 3.397 9 Delta Delta Delta 106 3.43 8 Delta Gamma 109 3.479 3 Delta Phi Omega 5 3.361 11 Delta Sigma Theta 12 3.157 14 Gamma Phi Beta 104 3.448 7 Kappa Alpha Theta 122 3.462 4 Kappa Delta 114 3.505 1 Kappa Kappa Gamma 116 3.452 5 Phi Mu 64 3.366 10 Pi Beta Phi 107 3.49 2 Zeta Phi Beta 8 3.35 12 Sorority Average 77 - Chapter # Members Chapter GPA Rank Alpha Epsilon Pi 35 3.53 1 Alpha Phi Alpha* 3 N/A - Alpha Tau Omega 44 3.406 6 Beta Theta Pi 40 3.28 11 Delta Chi 60 3.22 12 Delta Phi 51 3.11 16 Kappa Alpha Order 41 3.18 14 Kappa Alpha Psi 5 3.08 - Kappa Delta Rho 64 3.34 8 Kappa Sigma 71 3.19 13 Omega Psi Phi 2 N/A 18 Phi Gamma Delta 30 3.503 2 Phi Kappa Tau 11 3.470 4 Pi Kappa Alpha 42 3.154 15 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 42 3.38 7 Sigma Chi 42 3.33 9 Sigma Phi Epsilon 45 3.48 3 Sigma Pi 44 3.468 5 Fraternity Average 39 - Average Female GPA: 3.454 Average Male GPA: 3.335 All Undergraduate GPA: 3.404 Average Sorority GPA: 3.445 Average Fraternity GPA: 3.314 F/S Community GPA: 3.395 # Sorority Women: 1,083 # Fraternity Men: 711 # F/S Members: 1,794 # UG Women: 3,663 # UG Men: 2,654 # UG Students: 6,317 % UG Women in Sororities: 29.56% % UG Men in Fraternities: 26.78% % UG in F/S: 28.39% *Chapters with fewer than 5 members are not included in rankings to preserve student privacy Fall 2017 Overall Ranking Table Chapter GPA Rank Alpha Epsilon Pi 3.53 1 Kappa Delta 3.505 2 Phi Gamma Delta -

September 1959 Collegiates

of GAMMA PHI BETA ^ 1A' ^�.*. .�SffV^ fh ^ d P>. .S>;*r iifr$*^'^^ 'fflS ^^-', �3^-^r^t -./j^fc. 1 ''*�' ^t-aifWBit/---^^^^,^^ , ; '' . �r^"^*w^c^''' ����': A.4.p*^ CAMPUS SCENE, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH DAKOTA SEPTEMBER 1959 COLLEGIATES ON CAMPUS Sharon Mische of North Dakota State is Ihe Lettermen's Sweetheart and proudly displays Ihe trophy presented lo her by Ihe college athletes. Al Kappa Alpha's Dixie Boll, Mary Ellen Hovey (Woshingfon U.) was named Special Maid to Ihe K. A. Rose. She and her escort promenade under Ihe arched swords of Ihe "Confed eracy." Al McGill Universily, Joan Blundell (second from lefl) won the Silver Arrow in Intercollegiole archery compelilion. Also com peting for McGill were Gamma Phis Georgia Whitman, Mau reen Norwood and Joanne Seal, pictured from lefl. Gamma Phi Betos and Pi Lambda Phis ol Ihe University of Gamma Phis of Memphis S(o(� California joined forces for the annual Spring Sing and won "' as dolls in Ihe first place sweepstakes award. are pictured baby skif for fhe Deffo Zefo Follin, �"' "What Do We Think About ��� I" From left, front row, Barbara < more, Sandra Stobaugh, Cofol Dowdy and Connie Holland- H 1^ row, Ann Clark, Mary Frantei Caiman, Margaret McCullai 4 Shown receiving a hand Corinne Wells. some corsage and a kiss from an unidentified gentleman is Carole Piclure-prelly Gwen O/son poses Smith when she was wifh her posies as she was pre named Besf Dressed Girl sented as a Princess of Sigma Chi on fhe Bow/ing Green al fhe Universily of Soofhern Cali Sfofe l/niversity campus. -

Timeline of Fraternities and Sororities at Texas Tech

Timeline of Fraternities and Sororities at Texas Tech 1923 • On February 10th, Texas Technological College was founded. 1924 • On June 27th, the Board of Directors voted not to allow Greek-lettered organizations on campus. 1925 • Texas Technological College opened its doors. The college consisted of six buildings, and 914 students enrolled. 1926 • Las Chaparritas was the first women’s club on campus and functioned to unite girls of a common interest through association and engaging in social activities. • Sans Souci – another women’s social club – was founded. 1927 • The first master’s degree was offered at Texas Technological College. 1928 • On November 21st, the College Club was founded. 1929 • The Centaur Club was founded and was the first Men’s social club on the campus whose members were all college students. • In October, The Silver Key Fraternity was organized. • In October, the Wranglers fraternity was founded. 1930 • The “Matador Song” was adopted as the school song. • Student organizations had risen to 54 in number – about 1 for every 37 students. o There were three categories of student organizations: . Devoted to academic pursuits, and/or achievements, and career development • Ex. Aggie Club, Pre-Med, and Engineering Club . Special interest organizations • Ex. Debate Club and the East Texas Club . Social Clubs • Las Camaradas was organized. • In the spring, Las Vivarachas club was organized. • On March 2nd, DFD was founded at Texas Technological College. It was the only social organization on the campus with a name and meaning known only to its members. • On March 3rd, The Inter-Club Council was founded, which ultimately divided into the Men’s Inter-Club Council and the Women’s Inter-Club Council. -

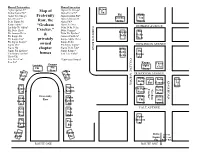

Map of Fraternity Row, the “Graham Cracker,”

Housed Fraternities: Housed Sororities Alpha Epsilon Pi* Map of Alpha Chi Omega* Sigma Alpha Sigma Phi* Alpha Delta Pi* Nu Phi Alpha Alpha Tau Omega Fraternity Alpha Epsilon Phi* Beta Theta Pi* Alpha Omicron Pi Gamma Tau Delta Sigma Phi Row, the Alpha Phi* Delta Omega Kappa Alpha* Alpha Xi Delta “Graham ROAD NORWICH Lambda Chi Alpha* Delta Delta Delta HOPKINS AVENUE Phi Delta Theta Cracker,” Delta Gamma* Kappa Phi Phi Gamma Delta & Delta Phi Epsilon* Delta Phi Kappa Psi Gamma Phi Beta* Delta Theta Phi Kappa Tau* privately Kappa Alpha Theta Phi Sigma Kappa* Kappa Delta Sigma Chi* owned Phi Sigma Sigma* DICKINSON AVENUE Sigma Nu chapter Sigma Delta Tau* Delta Sigma Phi Epsilon* Sigma Kappa * Delta Phi Tau Kappa Epsilon* houses Zeta Tau Alpha* Kappa Theta Chi Delta COLLEGE AVENUE COLLEGE Psi Zeta Beta Tau* *University Owned Zeta Psi* Kappa Theta Lambda Gamma Alpha Chi Chi Phi Theta Alpha Beta Alpha Beta PRINCETON AVENUE Theta Sigma Phi Alpha Alpha Delta Alpha Pi ROAD KNOX Delta Phi Gamma Xi Pi Phi Sigma Delta “Graham “Graham Sigma Phi Sigma Cracker” Kappa Delta Tau Kappa Sigma Tau Fraternity Alpha Alpha Delta Alpha Row Epsilon Chi Phi Epsilon Omega Pi Phi Epsilon Zeta Zeta YALE AVENUE Beta Tau Tau Alpha Alpha Phi Zeta Omicron Sigma Pi Psi Kappa Kappa Sigma Delta (across Alpha Chi Sigma Rt. 1 on Phi Knox Rd) ROUTE ONE ROUTE ONE . -

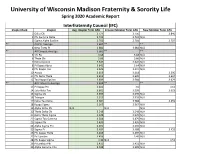

Spring 2020 Community Grade Report

University of Wisconsin Madison Fraternity & Sorority Life Spring 2020 Academic Report Interfraternity Council (IFC) Chapter Rank Chapter Avg. Chapter Term GPA Initiated Member Term GPA New Member Term GPA 1 Delta Chi 3.777 3.756 3.846 2 Phi Gamma Delta 3.732 3.732 N/A 3 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 3.703 3.704 3.707 ** All FSL Average 3.687 ** ** 4 Beta Theta Pi 3.681 3.682 N/A ** All Campus Average 3.681 ** ** 5 Chi Psi 3.68 3.68 N/A 6 Theta Chi 3.66 3.66 N/A 7 Delta Upsilon 3.647 3.647 N/A 8 Pi Kappa Alpha 3.642 3.64 N/A 9 Phi Kappa Tau 3.629 3.637 N/A 10 Acacia 3.613 3.618 3.596 11 Phi Delta Theta 3.612 3.609 3.624 12 Tau Kappa Epsilon 3.609 3.584 3.679 ** All Fraternity Average 3.604 ** ** 13 Pi Kappa Phi 3.601 3.6 3.61 14 Zeta Beta Tau 3.601 3.599 3.623 15 Sigma Chi 3.599 3.599 N/A 16 Triangle 3.593 3.593 N/A 17 Delta Tau Delta 3.581 3.588 3.459 18 Kappa Sigma 3.567 3.567 N/A 19 Alpha Delta Phi N/A N/A N/A 20 Theta Delta Chi 3.548 3.548 N/A 21 Delta Theta Sigma 3.528 3.529 N/A 22 Sigma Tau Gamma 3.504 3.479 N/A 23 Sigma Phi 3.495 3.495 N/A 24 Alpha Sigma Phi 3.492 3.492 N/A 25 Sigma Pi 3.484 3.488 3.452 26 Phi Kappa Theta 3.468 3.469 N/A 27 Psi Upsilon 3.456 3.49 N/A 28 Phi Kappa Sigma 3.44 N/A 3.51 29 Pi Lambda Phi 3.431 3.431 N/A 30 Alpha Gamma Rho 3.408 3.389 N/A Multicultural Greek Council (MGC) Chapter Rank Chapter Chapter Term GPA Initiated Member Term GPA New Member Term GPA 1 Lambda Theta Alpha Latin Sorority, Inc. -

Alpha Delta Pi

First Finest Forever Alpha Delta Pi In 1851, six students established Alpha Delta Pi as the rst secret society for women and consequently changed the college experience for generations to follow. Continuing the legacy of the founding women by pursuing opportunities to lead and grow in unchartered territory, Alpha Delta Pi seeks to enhance every member’s college experience while instilling values that remain relevant long after graduation. Joining Alpha Delta Pi means investing in a bond that has formed inuential leaders on Penn’s campus and across the world. The Alpha Delta Pi experience cultivates well-balanced leaders that continually affect positive change within the sorority as well as across Penn’s campus. Sisters are able to contribute and develop their skills and talents by becoming an ofcer or a committee member, while also nding opportunities for campus involvement through the extensive network within the chapter. Highly involved in organizations such as MERT, Big Brothers Big Sisters, Kite and Key, Varsity Athletics, and Wharton Women, the sisters of ADPi encourage each other to pursue meaningful involvement and excellence in whatever they undertake. Surrounded by innovative women and working towards a shared vision, Alpha Delta Pi women are leaders set apart by their values and well-rounded skill set. “Strive to become a well- balanced person by following the Alpha Delta Pi's active relationship with the Ronald McDonald House Charities demonstrate sisters' desire to positively contribute to their dictates of the four points surrounding community. Providing a home away from home for families with symbolized by our diamond- children undergoing treatment at nearby hospitals, the Ronald McDonald shaped badge: rst, House’s mission and vision holds great importance for Alpha Delta Pi sisters. -

Fall 2020 Community Grade Report Women's Organizations

Fall 2020 Community Grade Report Women's Organizations Dollars Service Organization Semester Cumulative Donated New Member (Total Members/New Council Hours per GPA** GPA* per Semester GPA ** Members) Member Member Alpha Kappa Alpha NPHC 3.048 3.079 11 - - (31/0) Delta Sigma Theta NPHC 2.965 3.169 - $1.14 FERPA Protected (22/21) Delta Zeta (31/12) PC 3.159 3.358 - - 2.815 Hermanas of N/A 3.318 3.478 - - 2.956 Leadership Assoc. (9/3) Phi Mu (31/9) PC 3.252 3.344 - $19.03 3.332 Sigma Gamma Rho NPHC 2.762 2.729 - - - (10/0) Zeta Phi Beta (3/0) NPHC 3.011 2.995 8.67 $25 - Zeta Tau Alpha (27/10) PC 3.187 3.307 - - 2.923 Men's Organizations Dollars Service Organization Semester Cumulative Donated New Member (Total Members/New Council Hours per GPA ** GPA* per Semester GPA ** Members) Member Member Alpha Phi Alpha (8/0) NPHC 2.734 2.784 1 - - Alpha Sigma Phi (20/0) IFC 3.024 3.096 - - - Kappa Alpha Psi (9/0) NPHC 2.409 2.636 - - - Omega Psi Phi (8/0) NPHC 2.156 2.619 - - - Phi Beta Sigma (9/0) NPHC 2.492 2.848 - - - Sigma Alpha Epsilon IFC 1.725 2.475 - - - (9/0) * For the purpose of this report, Cumulative Grade Point Average (GPA) refers to a student’s GPA from courses completed at USC Upstate and does not include GPAs that transferred from other colleges or universities. ** For categories with fewer than three members, grades are not made public in order to protect the privacy of academic records for those students; however, member grades are included in overall FSL averages. -

Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity Sourcebook, 2013-2014 This Sourcebook Is the Property Of

Alpha Chi Sigma Sourcebook A Repository of Fraternity Knowledge for Reference and Education Academic Year 2013-2014 Edition 1 l Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity Sourcebook, 2013-2014 This Sourcebook is the property of: ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Full Name Chapter Name ___________________________________________________ Pledge Class ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Date of Pledge Ceremony Date of Initiation ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Master Alchemist Vice Master Alchemist ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Master of Ceremonies Reporter ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Recorder Treasurer ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Alumni Secretary Other Officer Members of My Pledge Class ©2013 Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity 6296 Rucker Road, Suite B | Indianapolis, IN 46220 | (800) ALCHEMY | [email protected] | www.alphachisigma.org Click on the blue underlined terms to link to supplemental content. A printed version of the Sourcebook is available from the National Office. This document may be copied and distributed freely for not-for-profit purposes, in print or electronically, provided it is not edited or altered in any -

New-Member Exam

Kappa Delta New Member Examination Study Guide Kappa Delta Beliefs 1. Write the purpose of Kappa Delta Sorority. (4 points) The purpose of Kappa Delta Sorority is to promote true friendship among the college girls of our country by inculcating into their hearts and lives those principles of truth, of honor, of duty, without which there could be no true friendship. 2. Our Purpose was written over 100 years ago. Describe, in your own words, what it means to you today. (2 points) These answers will vary. Please give credit if the new member provides a thoughtful answer. 3. Write the Kappa Delta Object. (4 points) The object of Kappa Delta Sorority is the formation and perpetuation of good fellowship, friendship and sisterly love among its members; the encouragement of literature and education; the promotion of social interest; and the furtherance of charitable and benevolent purposes. 4. Our Object was also written over 100 year ago. What does it mean to you today? (2 points) These answers will vary. Please give credit if the new member provides a thoughtful answer. 5. Write the Kappa Delta Creed. (4 points) May we, sisters in Kappa Delta, strive each day to seek more earnestly the honorable and beautiful things. May we each day through love of those within our circle learn to know and understand better those without our circle. May the diamond shield that guards our love find us each day Truer, Wiser, More Faithful, More Loving and More Noble. 6. How will you strive to live our Creed? (2 point) These answers will vary. -

West Chester University Fraternity and Sorority Grade Report - Spring 2016

West Chester University Fraternity and Sorority Grade Report - Spring 2016 +/- Chapter/ Sem. +/- Cuml. +/- # of New New Mem New Mem Rank CHAPTER Council F15 Colony Size GPA F15 GPA F15 Members Sem GPA Cuml. GPA WCU Sororities 1 0 Alpha Delta Pi PHC 111 3.48 -0.01 3.48 0.01 2 0 Delta Phi Epsilon PHC 101 3.47 0.06 3.42 0.03 3 0 Zeta Tau Alpha PHC 126 3.46 0.05 3.38 0.02 4 2 Alpha Xi Delta PHC 124 3.43 0.10 3.35 0.03 5 -1 Phi Sigma Sigma PHC 105 3.42 0.05 3.34 0.01 5 0 Alpha Sigma Alpha PHC 95 3.42 0.08 3.38 0.00 5 3 Alpha Sigma Tau PHC 115 3.42 0.12 3.37 0.03 8 -1 Alpha Phi PHC 119 3.41 0.10 3.36 0.02 8 1 Delta Zeta PHC 99 3.41 0.11 3.29 0.06 10 4 Phi Mu PHC 60 3.29 0.08 3.19 0.01 3 3.29 3.41 11 n/a Delta Sigma Theta BLGC 8 3.15 n/a 3.17 n/a 8 3.15 3.17 12 3 Sigma Lambda Gamma BLGC 10 3.12 0.17 3.23 0.05 13 -1 Chi Upsilon Sigma BLGC 8 3.11 -0.11 3.19 -0.15 5 2.84 3.07 14 -4 Alpha Kappa Alpha BLGC 9 3.08 -0.21 3.27 0.02 15 -2 Mu Sigma Upsilon BLGC 5 3.03 -0.18 3.14 -0.08 16 n/a Zeta Phi Beta BLGC 7 2.98 n/a 3.47 n/a 3 2.72 2.99 17 -6 Sigma Gamma Rho BLGC 15 2.66 -0.62 3.02 -0.10 8 2.51 2.93 18 n/a Lambda Theta Alpha BLGC 6 2.64 n/a 2.95 n/a 6 2.64 2.95 WCU Fraternities 1 0 Pi Kappa Alpha IFC 87 3.37 0.07 3.30 0.06 8 3.11 3.35 2 0 Sigma Phi Epsilon IFC 57 3.29 0.01 3.32 -0.01 8 3.09 3.17 3 11 Lambda Alpha Upsilon BLGC 8 3.19 0.40 3.01 0.06 4 3 Sigma Pi IFC 107 3.12 0.07 3.10 0.03 10 3.08 3.20 5 6 Alpha Tau Omega IFC 54 3.11 0.14 3.27 0.22 5 3.31 3.27 5 1 Kappa Sigma IFC 60 3.11 0.05 3.11 -0.04 6 2.84 2.79 7 5 Pi Kappa Phi IFC 82 3.09 0.20 -

Spring 2020 Grade Report

Spring 2020 Grade Report All Fraternities & Sororities Rank Chapter Term GPA # of Members Deans List Provost List 1 Alpha Kappa Alpha 3.933 3 3 0 2 Zeta Phi Eta 3.853 71 64 25 3 Phi Delta Epsilon 3.832 52 47 23 4 Delta Gamma 3.819 94 83 35 5 Delta Phi Epsilon 3.769 84 68 23 6 Alpha Phi 3.742 90 79 16 7 Delta Phi Omega 3.734 10 8 5 8 Alpha Epsilon Phi 3.733 57 42 11 All NPC 3.732 472 382 113 9 Alpha Kappa Psi 3.729 22 18 5 All Sororities 3.727 495 398 119 10 Alpha Phi Alpha 3.727 4 3 0 All Coed Organizations 3.723 324 262 87 11 Phi Sigma Sigma 3.717 88 68 20 12 Phi Alpha Delta 3.703 58 45 15 All PFC 3.723 324 262 87 13 Phi Delta Theta 3.697 58 50 7 All Greek 3.683 1023 796 235 14 Alpha Phi Omega 3.666 93 72 16 All MFSC 3.636 28 19 6 15 Delta Sigma Theta 3.613 4 3 1 All UG Female Avg 3.580 3330 0 0 16 Pi Kappa Alpha 3.556 30 23 5 17 Alpha Theta Beta 3.543 59 42 8 All IFC 3.511 198 133 29 All Undergraduate Avg 3.480 6039 0 0 All Fraternities 3.514 203 136 29 18 Pi Lambda Phi 3.679 16 12 2 19 Delta Chi 3.427 13 7 0 20 Theta Tau 3.418 28 16 3 21 Phi Kappa Theta 3.355 46 23 11 22 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 3.353 25 15 3 All UG Male Avg 3.350 2709 0 0 23 Sigma Gamma Rho 3.268 5 1 0 24 Tau Epsilon Phi 3.180 10 3 1 Organizations wth less than 3 Members - Phi Iota Alpha * 1 * * - Lambda Theta Alpha * 1 * * Spring 2020 Grade Report Interfraternity Council Chapter New Members Initiated Members Total Membership Delta Chi 2 * 11 3.506 13 3.427 Phi Delta Theta 13 3.685 45 3.701 58 3.697 Phi Kappa Theta 8 3.058 38 3.423 46 3.355 Pi Kappa Alpha 7 3.292 23 3.636