Reinforced Concrete Failure Mechanisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alkali-Silica Reactivity: an Overview of Research

SHRP-C-342 Alkali-Silica Reactivity: An Overview of Research Richard Helmuth Construction Technology Laboratories, Inc. With contributions by: David Stark Construction Technology Laboratories, Inc. Sidney Diamond Purdue University Micheline Moranville-Regourd Ecole Normale Superieure de Cachan Strategic Highway Research Program National Research Council Washington, DC 1993 Publication No. SHRP-C-342 ISBN 0-30cL05602-0 Contract C-202 Product No. 2010 Program Manager: Don M. Harriott Project Maxtager: Inam Jawed Program AIea Secretary: Carina Hreib Copyeditor: Katharyn L. Bine Brosseau May 1993 key words: additives aggregate alkali-silica reaction cracking expansion portland cement concrete standards Strategic Highway Research Program 2101 Consti!ution Avenue N.W. Washington, DC 20418 (202) 334-3774 The publicat:Lon of this report does not necessarily indicate approval or endorsement by the National Academy of Sciences, the United States Government, or the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials or its member states of the findings, opinions, conclusions, or recommendations either inferred or specifically expressed herein. ©1993 National Academy of Sciences 1.5M/NAP/593 Acknowledgments The research described herein was supported by the Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP). SHRP is a unit of the National Research Council that was authorized by section 128 of the Surface Transportation and Uniform Relocation Assistance Act of 1987. This document has been written as a product of Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP) Contract SHRP-87-C-202, "Eliminating or Minimizing Alkali-Silica Reactivity." The prime contractor for this project is Construction Technology Laboratories, with Purdue University, and Ecole Normale Superieure de Cachan, as subcontractors. Fundamental studies were initiated in Task A. -

A Computational Study of the Shear Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Beams Affected from Alkali–Silica Reactivity Damage

materials Article A Computational Study of the Shear Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Beams Affected from Alkali–Silica Reactivity Damage Bora Gencturk 1,* , Hadi Aryan 1, Mohammad Hanifehzadeh 1, Clotilde Chambreuil 2 and Jianqiang Wei 3 1 Sonny Astani Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Southern California, 3620 S. Vermont Avenue, KAP 210, Los Angeles, CA 90089-2531, USA; [email protected] (H.A.); [email protected] (M.H.) 2 LMT—Laboratoire de Mécanique et Technologie, University Paris-Saclay, ENS Paris-Saclay, CNRS, 91190 Gif-sur-Yvette, France; [email protected] 3 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Massachusetts, Lowell, MA 01854-5104, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-(213)-821-1036; Fax: +1-(213)-744-1426 Abstract: In this study, an investigation of the shear behavior of full-scale reinforced concrete (RC) beams affected from alkali–silica reactivity damage is presented. A detailed finite element model (FEM) was developed and validated with data obtained from the experiments using several metrics, including a force–deformation curve, rebar strains, and crack maps and width. The validated FEM was used in a parametric study to investigate the potential impact of alkali–silica reactivity (ASR) degradation on the shear capacity of the beam. Degradations of concrete mechanical properties were correlated with ASR expansion using material test data and implemented in the FEM for Citation: Gencturk, B.; Aryan, H.; different expansions. The finite element (FE) analysis provided a better understanding of the failure Hanifehzadeh, M.; Chambreuil, C.; mechanism of ASR-affected RC beam and degradation in the capacity as a function of the ASR Wei, J. -

How to Make Concrete More Sustainable Harald Justnes1

Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology Vol. 13, 147-154, March 2015 / Copyright © 2015 Japan Concrete Institute 147 Scientific paper How to Make Concrete More Sustainable Harald Justnes1 A selected paper of ICCS13, Tokyo 2013. Received 12 November 2013, accepted 16 February 2015 doi:10.3151/jact.13.147 Abstract Production of cement is ranking 3rd in causes of man-made carbon dioxide emissions world-wide. Thus, in order to make concrete more sustainable one may work along one or more of the following routes; 1) Replacing cement in con- crete with larger amounts of supplementary cementing materials (SCMs) than usual, 2) Replacing cement in concrete with combinations of SCMs leading to synergic reactions enhancing strength, 3) Producing leaner concrete with less cement per cubic meter utilizing plasticizers and 4) Making concrete with local aggregate susceptible to alkali silica reaction (ASR) by using cement replacements, thus avoiding long transport of non-reactive aggregate. 1 Introduction SCMs, also uncommon ones like calcined marl 2. Replacing cement in concrete with combinations of The cement industry world-wide is calculated to bring SCMs leading to synergic reactions enhancing about 5-8% of the total global anthropogenic carbon strength dioxide (CO2) emissions. The general estimate is about 3. Producing leaner concrete with less cement per cubic 1 tonne of CO2 emission per tonne clinker produced, if meter utilizing plasticizers. fossil fuel is used and no measures are taken to reduce it. 4. Making concrete with local aggregate susceptible to The 3rd rank is not because cement is such a bad mate- alkali silica reaction (ASR) by using cement re- rial with respect to CO2 emissions, but owing to the fact placements, thus avoiding long transport of non- that it is so widely used to construct the infrastructure reactive aggregate and buildings of modern society as we know it. -

Formwork.Pdf

Formwork INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 DESIGN REQUIREMENTS ............................................................................................................................................... 4 FACTORS RELATING TO FORMWORK ........................................................................................................................... 6 HIGH WALL FORMWORK .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Timber Framed Formwork. ....................................................................................................................................... 7 SHEATHING ............................................................................................................................................................... 8 WALL TYING SYSTEMS .............................................................................................................................................. 8 CONSTRUCTION JOINTS ............................................................................................................................................ 9 SLIPFORM ............................................................................................................................................................... 10 CLIMBING OR JUMP FORMS .................................................................................................................................. -

Formation of Polymer Micro-Agglomerations in Ultralow-Binder-Content Composite Based on Lunar Soil Simulant

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Advances in Space Research 61 (2018) 830–836 www.elsevier.com/locate/asr Formation of polymer micro-agglomerations in ultralow-binder-content composite based on lunar soil simulant Tzehan Chen a, Brian J. Chow b, Ying Zhong a, Meng Wang b, Rui Kou b, Yu Qiao a,b,⇑ a Program of Materials Science and Engineering, University of California – San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA b Department of Structural Engineering, University of California – San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0085, USA Received 9 August 2017; received in revised form 25 October 2017; accepted 27 October 2017 Available online 6 November 2017 Abstract We report results from an experiment on high-pressure compaction of lunar soil simulant (LSS) mixed with 2–5 wt% polymer binder. The LSS grains can be strongly held together, forming an inorganic-organic monolith (IOM) with the flexural strength around 30–40 MPa. The compaction pressure, the number of loadings, the binder content, and the compaction duration are important factors. The LSS-based IOM remains strong from À200 °C to 130 °C, and is quite gas permeable. Ó 2017 COSPAR. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Binder content; Lunar regolith; Structural material; In-situ resource utilization 1. Introduction A major component of lunar soil is silica. While, once heated to above 1200 °C, silica grains can be fused In the next a few decades, building large-scale lunar together, the thermal processing consumes a large amount bases and/or research facilities on the Moon will probably of energy (Taylor and Meek, 2005). -

Properties and Applications of Fiber Reinforced Concrete

JKAU: Eng. Sci., Vol. 2, pp. 49-6~ (1410 A.H./19lJlI A.D.) Properties and Applications of Fiber Reinforced Concrete FAISAL FOUAD WAFA Associate Professor, Civil Engineering Department, Faculty ofEngineering, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. ABSTRACT. Fiber reinforced concrete (FRC) is a new structural material which is gaining increasing importance. Addition of fiber reinforcement in discrete form improves many engineering properties of concrete. Currently, very little research work is being conducted within the King dom using this new material. This paper describes the different types of fib ers and the application of FRC in different areas. It also presents the result of research about the mechanical properties of FRC using straight as well as hooked steel fibers available in the region, Introduction Concrete is weak in tension and has a brittle character. The concept of using fibers to improve the characteristics of construction materials is very old. Early applications include addition of straw to mud bricks, horse hair to reinforce plaster and asbestos to reinforce pottery. Use of continuous reinforcement in concrete (reinforced con crete) increases strength and ductility, but requires careful placement and labour skill. Alternatively, introduction offibers in discrete form in plain or reinforced con crete may provide a better solution. The modern development of fiber reinforced concrete (FRC) started in the early sixties(1J. Addition of fibers to concrete makes it a homogeneous and isotropic material. When concrete cracks, the randomly oriented fibers start functioning, arrest crack formation and propagation, and thus improve strength and ductility. The failure modes of FRC are either bond failure be tween fiber and matrix or material failure. -

Design Procedures for Prestressed Reinforced Concrete

THE DESIGN PROCEDURES FOR PRESTRESSED REINFORCED CONCRETE by DEVENDRA M. DHARIA B. S. t Stanford University, 1961 A MASTER'S REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Civil Engineering KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1963 Approved by: jOfu Professor Do ^u,' ^•^^ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SYNOPSIS ti INTRODUCTION 1 LIFE HISTORY OF PRESTRESSED MEMBER UNDER FLEXURE ... 2 PRE3TRES3ED VS. REINFORCED CONCRETE 10 PRINCIPLES OF REINFORCED CONCRETE AND PRESTRESSED CONCRETE 13 ANALYSIS OF SECTIONS FOR FLEXURE 14 THE ULTIMATE STRENGTH OF PRESTRESSED BEAMS 18 DESIGN OF SECTIONS 20 ULTIMATE DESIGN 32 SHEAR 34 FLEXURAL BOND AT INTERMEDIATE POINTS 37 DESIGN OF A PRESTRESSED CONCRETE BRIDGE GIRDER .... 38 CONCLUSION 73 ACKNOWLEDGMENT 74 APPENDIX I, READING REFERENCES ... 75 APPENDIX II, BIBLIOGRAPHY 76 APPENDIX III, NOTATIONS 77 APPENDIX IV, LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 79 ii TEE DESIGN PROCEDURES FOR PRESTRESSED REINFORCED CONCRETE 1 By DEVENDRA M. DHARIA SYNOPSIS Prestressed concrete design procedures are relatively new tools, with which designers will give more attention to the as- pect of practical usage. The intent of this report is to show the proper procedures which an engineer must follow and the pre- cautions which he must exercise in any reinforced concrete de- sign so that the design can be done effectively. "Prestressing" means the creation of stresses in a struc- ture before it is loaded. These stresses are artificially im- parted so as to counteract those occurring in the structure un- der loading. Thus, in a reinforced concrete beam, a counter- bending is produced by the application of eccentric compression forces acting at the ends of the beam. -

ASR) and Alkali-Carbonate Reaction (ACR)

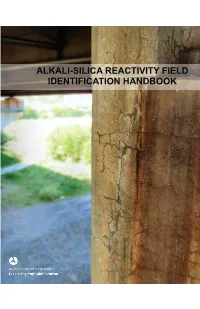

ALKALI-SILICA REACTIVITY FIELD IDENTIFICATION HANDBOOK Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA-HIF-12-022 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Alkali-Silica Reactivity Field Identification Handbook December 2011 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Thomas, M.D.A., Fournier, B., Folliard, K.J., Resendez, Y.A. 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. The Transtec Group, Inc. 6111 Balcones Drive Austin, TX 78731 11. Contract or Grant No. DTFH61-06-D-00035 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Office of Pavement Technology Final Report December 2011 Federal Highway Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue, DE Washington, DC 20590 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Contracting Officer’s Technical Representative (COTR): Gina Ahlstrom, HIPT-20 16. Abstract Two types of alkali-aggregate reaction (AAR) are currently recognized depending on the nature of the reactive mineral; these are alkali-silica reaction (ASR) and alkali-carbonate reaction (ACR). Both types of reaction can result in expansion and cracking of concrete elements, lead ing to a reduction in the service life of concrete structures. This handbook serves as an illustrated guide to assist users in detecting and distin guishing ASR in the field from other types of damages. 17. Key Words 18. Distribution Statement Alkali-silica reactivity, alkali-aggregate reaction, reactive No restrictions. This document is available to the public through the Na aggregates, concrete durability, field identification, concrete tional Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161. -

Reinforced Concrete Design

FALL 2013 C C Reinforced Concrete Design CIVL 4135 • ii 1 Chapter 1. Introduction 1.1. Reading Assignment Chapter 1 Sections 1.1 through 1.8 of text. 1.2. Introduction In the design and analysis of reinforced concrete members, you are presented with a problem unfamiliar to most of you: “The mechanics of members consisting of two materials.” To compound this problem, one of the materials (concrete) behaves differently in tension than in compression, and may be considered to be either elastic or inelastic, if it is not neglected entirely. Although we will encounter some peculiar aspects of behavior of concrete members, we will usually be close to a solution for most problems if we can apply the following three basic ideas: • Geometry of deformation of sections will be consistent under given types of loading; i.e., moment will always cause strain to vary linearly with distance from neutral axis, etc. • Mechanics of materials will allow us to relate stresses to strains. • Sections will be in equilibrium: external moments will be resisted by internal moment, external axial load will be equal to the sum of internal axial forces. (Many new engineers overly impressed speed and apparent accuracy of modern structural analysis computational procedures think less about equilibrium and details). We will use some or all of these ideas in solving most of the analysis problems we will have in this course. Design of members and structures of reinforced concrete is a problem distinct from but closely related to analysis. Strictly speaking, it is almost impossible to exactly analyze a concrete structure, and to design exactly is no less difficult. -

Economical and Crack-Free High-Performance Concrete for Pavement and Transportation Infrastructure Construction

Economical and Crack-Free High-Performance Concrete for Pavement and Transportation Infrastructure Construction Prepared by: Kamal H. Khayat, PhD, P.Eng. (principal investigator) Iman Mehdipour, PhD Candidate (student) Missouri University of Science and Technology Final Report Prepared for Missouri Department of Transportation May 2017 Project TR201503 Report cmr17-007 TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. cmr 17-007 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Economical and Crack-Free High-Performance Concrete for Pavement and June 30, 2016 Transportation Infrastructure Construction Published: May 2017 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Kamal H. Khayat, PhD, P.Eng. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1431-0715 00047062 Iman Mehdipour, PhD Candidate http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6841-3907 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. Center for Transportation Infrastructure and Safety/UTC program Missouri University of Science and Technology 11. Contract or Grant No. 220 Engineering Research Lab, Rolla, MO 65409 MoDOT project #TR2015-03 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Missouri Department of Transportation (SPR) Final Report (June 23, 2014-June 30, Construction and Materials Division 2016) P.O. Box 270, Jefferson City, MO 65102 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. MoDOT research reports are available in the Innovation Library at http://www.modot.org/services/or/byDate.htm. This report is available at https://library.modot.mo.gov/RDT/reports/TR201503/cmr17-007.pdf 16. -

Mechanical Properties of Concrete and Steel Reinforced Concrete (RC

Mechanical Properties of Concrete and Steel Reinforced Concrete (RC, also called RCC for Reinforced Cement Concrete) is a widely used construction material in many parts the world. Due to the ready availability of its constituent materials, the strength and economy it provides and the flexibility of its forms, RC is often preferred to steel, masonry or timber in building structures. From a structural analysis and design point of view, RC is a complex composite material. It provides a unique coupling of two materials (concrete, steel) with entirely different mechanical properties. Stress-Strain Curve for Concrete Concrete is much stronger in compression than in tension (tensile strength is of the order of one-tenth of compressive strength). While its tensile stress-strain relationship is almost linear [Fig. 1.1(i)], the stress () vs. strain () relationship in compression is nonlinear. Fig. 1.1(ii) shows a typical set of such curves. These curves are different for various ultimate strengths of concrete, particularly the peak stress and ultimate strain. They consist of an Stress initial relatively elastic portion in Stress f w hich stress and strain are closely c proportional, then begin to curve to the horizontal, reaching maximum stress, i.e., the compressive strength f , at a strain of approximately 0.002, c and finally show a descending branch. They also show that concrete Strain, 0.002 Strain, of lower strength are more ductile; Fig. 1.1: - curves of Concrete in (i) tension, (ii) compression i.e., fail at higher strains. The tensile strength as well as the modulus of elasticity of concrete are both proportional to the square-root of its ultimate strength, fc, and can be approximated by ft = 6 fc…………(1.1), Ec = 57500 fc…………(1.2) [in psi]. -

Concrete Deterioration

PDHonline Course S155 (1 PDH) Concrete Deterioration Instructor: D. Matthew Stuart, P.E., S.E., F.ASCE, F.SEI, SECB, MgtEng 2013 PDH Online | PDH Center 5272 Meadow Estates Drive Fairfax, VA 22030-6658 Phone & Fax: 703-988-0088 www.PDHonline.org www.PDHcenter.com An Approved Continuing Education Provider www.PDHcenter.com www.PDHonline.org Concrete Deterioration Reinforced concrete is a very versatile construction material. Properly designed concrete structures are both strong and durable. However, concrete structures are vulnerable to a number of factors that can cause deterioration. Deterioration can result in loss of strength and unsafe conditions. Therefore it is important to have an understanding of the vulnerabilities of concrete structures in order to help minimize long-term repair and maintenance costs. Source: Interiors & Sources Concrete Basics Concrete consists of three basic ingredients; Portland cement, aggregates (both fine/sand and coarse/stone) and water. The ingredients are mixed to form a flowable mixture that can be placed in forms that mold the concrete into the desired shape. After the concrete ingredients are mixed, the Portland cement begins to hydrate. This process involves the chemical bonding of the cement with the water molecules, which will eventually form a hardened matrix. Source: Concrete Network © D. Matthew Stuart 1 www.PDHcenter.com www.PDHonline.org Hardened concrete has very good compressive strength, but very poor tensile strength. Concrete tensile strength is about 10% of its compressive strength. Steel on the other hand has both very good tensile strength and thermal properties that are compatible with concrete. The complementary properties of concrete and steel are combined to provide reinforced concrete structures that are capable of supporting considerable loads.