Chapter 2 Continental Attractions Domestic Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARNIVAL and OTHER SEASONAL FESTIVALS in the West Indies, USA and Britain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SAS-SPACE CARNIVAL AND OTHER SEASONAL FESTIVALS in the West Indies, U.S.A. and Britain: a selected bibliographical index by John Cowley First published as: Bibliographies in Ethnic Relations No. 10, Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, September 1991, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL John Cowley has published many articles on blues and black music. He produced the Flyright- Matchbox series of LPs and is a contributor to the Blackwell Guide To Blues Records, and Black Music In Britain (both edited by Paul Oliver). He has produced two LPs of black music recorded in Britain in the 1950s, issued by New Cross Records. More recently, with Dick Spottswood, he has compiled and produced two LPs devoted to early recordings of Trinidad Carnival music, issued by Matchbox Records. His ‗West Indian Gramophone Records in Britain: 1927-1950‘ was published by the Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations. ‗Music and Migration,‘ his doctorate thesis at the University of Warwick, explores aspects of black music in the English-speaking Caribbean before the Independence of Jamaica and Trinidad. (This selected bibliographical index was compiled originally as an Appendix to the thesis.) Contents Introduction 4 Acknowledgements 7 How to use this index 8 Bibliographical index 9 Bibliography 24 Introduction The study of the place of festivals in the black diaspora to the New World has received increased attention in recent years. Investigations range from comparative studies to discussions of one particular festival at one particular location. It is generally assumed that there are links between some, if not all, of these events. -

Tramway Renaissance

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com OCTOBER 2018 NO. 970 FLORENCE CONTINUES ITS TRAMWAY RENAISSANCE InnoTrans 2018: Looking into light rail’s future Brussels, Suzhou and Aarhus openings Gmunden line linked to Traunseebahn Funding agreed for Vancouver projects LRT automation Bydgoszcz 10> £4.60 How much can and Growth in Poland’s should we aim for? tram-building capital 9 771460 832067 London, 3 October 2018 Join the world’s light and urban rail sectors in recognising excellence and innovation BOOK YOUR PLACE TODAY! HEADLINE SUPPORTER ColTram www.lightrailawards.com CONTENTS 364 The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association OCTOBER 2018 Vol. 81 No. 970 www.tautonline.com EDITORIAL EDITOR – Simon Johnston [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOr – Tony Streeter [email protected] WORLDWIDE EDITOR – Michael Taplin 374 [email protected] NewS EDITOr – John Symons [email protected] SenIOR CONTRIBUTOR – Neil Pulling WORLDWIDE CONTRIBUTORS Tony Bailey, Richard Felski, Ed Havens, Andrew Moglestue, Paul Nicholson, Herbert Pence, Mike Russell, Nikolai Semyonov, Alain Senut, Vic Simons, Witold Urbanowicz, Bill Vigrass, Francis Wagner, Thomas Wagner, 379 Philip Webb, Rick Wilson PRODUCTION – Lanna Blyth NEWS 364 SYSTEMS FACTFILE: bydgosZCZ 384 Tel: +44 (0)1733 367604 [email protected] New tramlines in Brussels and Suzhou; Neil Pulling explores the recent expansion Gmunden joins the StadtRegioTram; Portland in what is now Poland’s main rolling stock DESIGN – Debbie Nolan and Washington prepare new rolling stock manufacturing centre. ADVertiSING plans; Federal and provincial funding COMMERCIAL ManageR – Geoff Butler Tel: +44 (0)1733 367610 agreed for two new Vancouver LRT projects. -

Opportunities for Recreation in Pre-Industrial Times

Opportunities for Recreation in Pre-Industrial times The working life of a peasant was long and hard, but there were many holidays: Most holidays were determined by the church holy days. At Christmas there were twelve days of leisure and recreation until the twelfth night, a week at Easter and time off at Whitsun. There were occasional breaks from work – wakes, fairs, mops, market days, weddings, funerals. Depending on the type of holiday, certain entertainments and food were provided by the church or Lord of the Manor. Laws dictated that young men practised their archery but many ignored that and played ball games instead. Gambling was a means of getting rich quick so lots of activities allowed the opportunity for gambling: cock fighting, bare-knuckle boxing, bear-baiting. In the Middle Ages, leisure time was something for the whole community: everyone joined in: the pub was a gathering place for gambling, drinking, courtship, gossip and playing games. Weekly markets allowed people to trade – a meeting place for town and country people: a chance to buy and sell goods – just like modern markets and boot sales ! The village square was transformed on market days: entertainments and leisure activities were laid on: bull baiting, bear baiting, games, contests, rides, cock fighting, smock races for women, jugglers, musicians, puppet shows !! Local Wakes • The churches of small rural towns and villages in Britain all have a foundation (veneration) day, to honour the Patron Saint of the church. These special days became local holidays ‘holydays’, whereby a visit to church was followed by a festival. -

Streets of Olsztyn

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com MARCH 2016 NO. 939 TRAMS RETURN TO THE STREETS OF OLSZTYN Are we near a future away from the overhead line? Blizzards cripple US transit lines Lund begins tram procurement plan Five shortlisted for ‘New Tube’ stock ISSN 1460-8324 £4.25 BIM for light rail Geneva 03 DLR innovation cuts Trams meeting the both cost and risk cross-border demand 9 771460 832043 “On behalf of UKTram specifically Voices from the industry… and the industry as a whole I send V my sincere thanks for such a great event. Everything about it oozed quality. I think that such an event shows any doubters that light rail in the UK can present itself in a way that is second to none.” Colin Robey – Managing Director, UKTram 27-28 July 2016 Conference Aston, Birmingham, UK The 11th Annual UK Light Rail Conference and exhibition brings together over 250 decision-makers for two days of open debate covering all aspects of light rail operations and development. Delegates can explore the latest industry innovation within the event’s exhibition area and Innovation Zone and examine LRT’s role in alleviating congestion in our towns and cities and its potential for driving economic growth. Topics and themes for 2016 include: > Safety and security in street-running environments > Refurbishment vs renewal? Book now! > Low Impact Light Rail > Delivering added value from construction and modernisation To secure your place > Managing timetable change and passenger disruption please call > Environmental considerations for LRT construction > Selling light rail: Who? When? How? +44 (0) 1733 367600 > What the Luxembourg Rail Protocol means for light rail or visit > Tram-Train: Alternative perspectives > Where next for UK LRT? www.mainspring.co.uk > Major project updates SUPPORTED BY ORGANISED BY 100 CONTENTS The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association MARCH 2016 Vol. -

Thinking Aloud Ix This Monday Is Whit Monday. Many People Will Hardly

Thinking aloud ix This Monday is Whit Monday. Many people will hardly remember it since the Spring Bank Holiday replaced it. Whit Monday was the first Bank Holiday granted in 1871, Christmas Day and Easter Monday were added. This Sunday is Whitsunday, the New Testament reminds us of the help and support given to us by God in His Holy Spirit. It was a very popular day for Baptism when white is traditionally worn, hence Whit or White Sunday. It’s a forward looking festival, God’s support for all we are doing and going to do. Lockdown is being relaxed a little on this Whit Monday, but life remains with a need for caution. We must remember that there are many who are still advised to self-isolate, there are many others who remain cautious for various reasons and will not be rushing out to the shops to buy the latest treat from Birds’. As we look toward to a more normal future it is important we continue to support the elderly and the vulnerable, we maintain our new friendships with neighbours and treasure close relationships with family and friends again. We still need to support in our prayers the NHS and carers and everyone who restlessly works to keep life normal for us. There are still thousands who are bereaved. The message of Whitsun is living with the support of the hand of the Creator God as we remember we are hopefully moving slowly beyond Coronavirus with enhanced compassion, support, and encouragement for all we meet. Last weekend saw another important celebration, that of our Muslim friends, the keeping of Eid. -

This Month, May, Sunday 10Am Worship at St James Point Lonsdale (June at St George’S Queenscliff)

THIS MONTH, MAY, SUNDAY 10AM WORSHIP AT ST JAMES POINT LONSDALE (JUNE AT ST GEORGE’S QUEENSCLIFF) Dear people of St George's and St James', A book that I keep coming back to around this “Pentecost” time of year is “The Go-Between God”, first published in 1973 by Bishop John V. Taylor. Some of his words: “...the primary effect of the Pentecost experience was to fuse the individuals of the company into a fellowship which in the same moment was caught up into the life of the risen Lord. In a new awareness of Him and of one another they burst into praise, and the world came running for an explanation. In other words, the gift of the Holy Spirit in the fellowship of the church first enables Christians to “be”. And only as a consequence of that sends them to do and to speak”. I suppose that these days we don't often see people “”running to us for an explanation”” about who we are and what we believe ! But we do need to be alert to welcome and support those (often shy) “searchers” who might , from time to time, ask us tricky questions... or even drift into our church services. • Let us be confident and know that as the Holy Spirit dwells in us we will be given the right words and the right actions appropriate to the occasion. Please feel free to contact me by phone or email if there is anything I can do for you whilst Peter is on leave. Tim Gibson – ph. -

Henry Dean Quinby III Collection of Photographs and Correspondence, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb3779n8tj No online items Henry Dean Quinby III Collection of Photographs and Correspondence, ca. 1933-1957 Processed by Regina Kammer. Harmer E. Davis Transportation Library Institute of Transportation Studies 409 McLaughlin Hall University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-1720 Phone: (510) 642-3604 Fax: (510) 642-9180 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/ITSL © 2006 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Henry Dean Quinby III Collection NS4270 1 of Photographs and Correspondence, ca. 1933-1957 Descriptive Summary Collection Title: Henry Dean Quinby III Collection of Photographs and Correspondence, Date: ca. 1933-1957 Collection Number: NS4270 Creator: Quinby, Henry Dean III, 1925-1978 Extent: ca. 4 linear ft.(5 document boxes, 4 print boxes) Repository: University of California, Berkeley. Institute of Transportation Studies. Library. Berkeley, California 94720-1720 Physical location: This collection is stored off-campus at NRLF. Please contact ITS Library staff for access to the materials. Languages Represented: Collection materials are chiefly in English, with some correspondence and ephemera in German. Abstract: Photographs of street-railroads (cars and tracks) taken by or collected by Henry Dean Quinby III. The collection also includes postcards of street-cars, paper ephemera associated with street-railroads, and correspondence from other street-car enthusiasts. Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the Harmer E. Davis Transportation Library. All requests for permission to reproduce photographs or publish manuscript materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of the Library. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Harmer E. -

2020 Book News Welcome to Our 2020 Book News

2020 Book News Welcome to our 2020 Book News. It’s hard to believe another year has gone by already and what a challenging year it’s been on many fronts. We finally got the Hallmark book launched at Showbus. The Red & White volume is now out on final proof and we hope to have copies available in time for Santa to drop under your tree this Christmas. Sorry this has taken so long but there have been many hurdles to overcome and it’s been a much bigger project than we had anticipated. Several other long term projects that have been stuck behind Red & White are now close to release and you’ll see details of these on the next couple of pages. Whilst mentioning bigger projects and hurdles to overcome, thank you to everyone who has supported my latest charity fund raiser in aid of the Christie Hospital. The Walk for Life challenge saw me trekking across Greater Manchester to 11 cricket grounds, covering over 160 miles in all weathers, and has so far raised almost £6,000 for the Christie. You can read more about this by clicking on the Christie logo on the website or visiting my Just Giving page www.justgiving.com/fundraising/mark-senior-sue-at-60 Please note our new FREEPOST address is shown below, it’s just: FREEPOST MDS BOOK SALES You don’t need to add anything else, there’s no need for a street name or post code. In fact, if you do add something, it will delay the letter or could even mean we don’t get it. -

Pearce Higgins, Selwyn Archive List

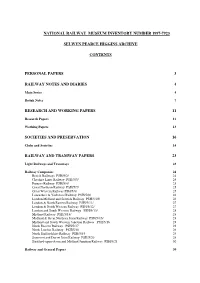

NATIONAL RAILWAY MUSEUM INVENTORY NUMBER 1997-7923 SELWYN PEARCE HIGGINS ARCHIVE CONTENTS PERSONAL PAPERS 3 RAILWAY NOTES AND DIARIES 4 Main Series 4 Rough Notes 7 RESEARCH AND WORKING PAPERS 11 Research Papers 11 Working Papers 13 SOCIETIES AND PRESERVATION 16 Clubs and Societies 16 RAILWAY AND TRAMWAY PAPERS 23 Light Railways and Tramways 23 Railway Companies 24 British Railways PSH/5/2/ 24 Cheshire Lines Railway PSH/5/3/ 24 Furness Railway PSH/5/4/ 25 Great Northern Railway PSH/5/7/ 25 Great Western Railway PSH/5/8/ 25 Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway PSH/5/9/ 26 London Midland and Scottish Railway PSH/5/10/ 26 London & North Eastern Railway PSH/5/11/ 27 London & North Western Railway PSH/5/12/ 27 London and South Western Railway PSH/5/13/ 28 Midland Railway PSH/5/14/ 28 Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway PSH/5/15/ 28 Midland and South Western Junction Railway PSH/5/16 28 North Eastern Railway PSH/5/17 29 North London Railway PSH/5/18 29 North Staffordshire Railway PSH/5/19 29 Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway PSH/5/20 29 Stratford-upon-Avon and Midland Junction Railway PSH/5/21 30 Railway and General Papers 30 EARLY LOCOMOTIVES AND LOCOMOTIVES BUILDING 51 Locomotives 51 Locomotive Builders 52 Individual firms 54 Rolling Stock Builders 67 SIGNALLING AND PERMANENT WAY 68 MISCELLANEOUS NOTEBOOKS AND PAPERS 69 Notebooks 69 Papers, Files and Volumes 85 CORRESPONDENCE 87 PAPERS OF J F BRUTON, J H WALKER AND W H WRIGHT 93 EPHEMERA 96 MAPS AND PLANS 114 POSTCARDS 118 POSTERS AND NOTICES 120 TIMETABLES 123 MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS 134 INDEX 137 Original catalogue prepared by Richard Durack, Curator Archive Collections, National Railway Museum 1996. -

Portland's Big Step

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE HEADLINES l Grand Paris Express project approved l Chicago invites new L-Train bids l New cross-industry lobbying group formed CROSSING THE RIVER: PORtland’s big step 120 years of the Manx Electric Railway Budapest renewals Czech car building The challenges of From Tatra to modernising one PRAGOIMEX: of Europe’s Proven tram largest tramways technology MAY 2013 No. 905 WWW . LRTA . ORG l WWW . TRAMNEWS . NET £3.80 TAUT_1305_Cover.indd 1 04/04/2013 16:59 Grooved rail to carry you far into the future Together we make the difference At Tata Steel, we believe that the secret to developing rail products and services that address the demands of today and tomorrow, lies in our lasting relationships with customers. Our latest innovation is a high performance grooved rail that has three times wear resistance* and is fully weld-repairable, responding to our customers’ needs for reduced life cycle costs. Tata Steel Tata Steel Rail Rail 2 Avenue du Président Kennedy PO Box 1, Brigg Road 78100 Saint Germain en Laye Scunthorpe, DN16 1BP France UK T: +33 (0) 139 046 300 T: +44 (0) 1724 402112 F: +33 (0) 139 046 344 F: +44 (0) 1724 403442 www.tatasteelrail.com [email protected] *Compared to R260 Untitled-2 1 03/04/2013 11:26 TS_Rail Sector Ad_Revised.indd 1 25/09/2012 08:57 Contents The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association 164 News 164 MAY 2013 Vol. 76 No. 905 European electrified transport lobbying group launched; Not- www.tramnews.net tingham enters intensive works phase; US public transport’s EDITORIAL 57-year high; 200km Grand Paris Express metro network Editor: Simon Johnston approved; Chicago invites bid for next-generation L-train cars; Tel: +44 (0)1832 281131 E-mail: [email protected] Eaglethorpe Barns, Warmington, Peterborough PE8 6TJ, UK. -

What Is Pentecost (Or Whitsun)?

What is Pentecost (or Whitsun)? Pentecost is a Christian holy day that celebrates the coming of the Holy Spirit 40 days after Easter. Some Christian denominations consider it the birthday of the Christian church and celebrate it as such. Originally, Pentecost was a Jewish holiday held 50 days after Passover. One of three major feasts during the Jewish year, it celebrated Thanksgiving for harvested crops. However, Pentecost for Christians means something far different. Before Jesus was crucified, he told his disciples that the Holy Spirit would come after him: And I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Counselor to be with you forever — the Spirit of truth. The world cannot accept him, because it neither sees him nor knows him. But you know him, for he lives with you and will be in you. I will not leave you as orphans; I will come to you. John 14:16–18 And 40 days after Jesus was resurrected (10 days after he ascended into heaven), that promise was fulfilled when Peter and the early Church were in Jerusalem for Pentecost: When the day of Pentecost came, they were all together in one place. Suddenly a sound like the blowing of a violent wind came from heaven and filled the whole house where they were sitting. They saw what seemed to be tongues of fire that separated and came to rest on each of them. All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit enabled them. Acts 2:1–4 Although many North American Christians hardly notice Pentecost today, traditional European churches consider it a major feast day. -

English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions About Black People in England

Trish Bater 080207052 ‘Blacking Up’: English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions about Black People in England Submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy by Patricia Bater National Centre for English Cultural Tradition March 2013 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Trish Bater 080207052 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the custom of white people blacking their faces and its continuation at a time when society is increasingly aware of accusations of racism. To provide a context, an overview of the long history of black people in England is offered, and issues about black stereotypes, including how ‘blackness’ has been perceived and represented, are considered. The historical use of blackface in England in various situations, including entertainment, social disorder, and tradition, is described in some detail. It is found that nowadays the practice has largely been rejected, but continues in folk activities, notably in some dance styles and in the performance of traditional (folk) drama. Research conducted through participant observation, interview, case study, and examination of web-based resources, drawing on my long familiarity with the folk world, found that participants overwhelmingly believe that blackface is a part of the tradition they are following and is connected to its past use as a disguise. However, although all are aware of the sensitivity of the subject, some performers are fiercely defensive of blackface, while others now question its application and amend their ‘disguise’ in different ways.