THE BOOK of 1 and 2 SAMUEL the Book of Samuel Tells a Story. It Is Not

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* Where Did the Israelites Get the Ark After the Philistines Defeated Them at Aphek? (4:3-4) 1. Ramah 2. Ephraim 3. Shiloh (3) 4

* Where did the Israelites get the ark after the Philistines 4. What did the Philistines capture from the Israelites? defeated them at Aphek? (4:3-4) (4:11) 1. Ramah 1. All the Israelites’ provisions 2. Ephraim 2. All the Israelites’ cattle 3. Shiloh 3. The ark of God (3) (3) 1. Who brought the ark of the covenant from Shiloh to 5. Who died in the battle where the ark of God was the Israelite camp? (4:4) captured? (4:11) 1. Hophni 1. Samuel and Eli 2. Phinehas 2. Hophni and Phinehas 3. Both answers are correct. 3. Samuel and Hannah (3) (3) 2. What happened when the ark of the covenant came * How old was Eli when he died? (4:14-15, 18) into the Israelite camp? (4:5) 1. 98 years old 1. All Israel shouted and the ground shook. 2. 88 years old 2. A thunderstorm came on the camp. 3. 108 years old 3. Both answers are correct. (3) (3) 3. How did the Philistines feel when they heard the 6. What happened when Eli found out that the Philistines shouting in the Israelite camp? (4:7) had captured the ark? (4:18) 1. They were excited. 1. He died. 2. They were afraid. 2. He prayed. 3. They were happy. 3. He sobbed. (3) (3) * How many Israelite foot soldiers died in the battle * How long did Eli lead Israel? (4:18) after they brought the ark into the camp? (4:10) 1. 20 years 1. 30,000 2. 30 years 2. 20,000 3. -

Ichabod by Dean Taylor

ate in the 1950s Leonard Ravenhill wrote a book thatquicklybecameaclassiconthesubjectofre- Why, when a people have Lvival entitled Why Revival Tarries.Itaddressedthe perplexing question: If God earnestly desires to pour His experienced a genuine gracious Spirit onto all flesh, then what is preventing it? presence and outpouring In other words, what is stopping us from experiencing thisoutpouring,andwhatwouldittakeforustoexperi- of the living God, would they encerealrevivallikewehavereadabout?Ithinkitisa turn away from it and question that does indeed challenge each of us as we long for more from God and desire to see true revival in our choose another way? day. But perhaps the thought that should vex us even more than why revival tarries, is the question—why does revival leave? Why, when a people have experienced a genuine presence and outpouring of the living God, wouldtheyturnawayfromitandchooseanotherway? As I have studied revival and church history, the ques- tionthatoftentroublesmewhenlookingataparticular work of God is—what happened that made this group lose every trace of all that God had done through them? Why doesthegloryofGodleave?TheLancasterrevivalsofthe 1950s, the Wesleyan revivals of the 1700s and 1800s, the East African revivals of the 1940s, and even the famous Welch Revival of 1904 are all for the most part gone. Why? Ichabod by Dean Taylor In the Old Testament, there was just one word that described this tragic state that occurred when the glory of God had departed—Ichabod. In 1 Samuel 4, the Scrip- tures take us to a tragic scene in Shiloh. It was here that thearkofGodandHistabernaclehadremainedforover 340 years. Through good times and bad, faithfulness and backsliding, God’s “glory”, at least in some measure, was alwaystheredwellingoverthemercyseatoftheark.But that would soon change. -

“Ichabod: God's Glory, Gone!”

“Ichabod: God’s Glory, Gone!” by Greg Smith-Young (Elora-Bethany Pastoral Charge) First in a series on the story of God’s Ark in 1st Samuel 4-6 1st Samuel 4 July 3, 2016 For three Sundays, starting today, I am going to dive into a peculiar episode. It is in 1st Samuel, chapters 4-6. It is weird, and it is wise. I Imagine we are in a rugged valley. Up one side camps the Philistine army. The Philistines are relatively new to this land of Canaan, maybe a few generations. Their ancestors sailed in from islands in the Aegean and settled along Canaan’s coast. That is good land. They’ve built five fortress cities. They are expanding north, south and east, pressing against their neighbours. Especially Israel.1 Up the other side of the valley is the Israelite army. We are generations after the Lord (through Joshua) led Israel into this Land of Promise. We are even longer after God (through Moses) brought Israel out of slavery in Egypt. And even longer after God (through Abraham and Sarah) began God’s rescue mission for all peoples of the earth, through this one tiny and unlikely people. God called and formed Israel within a precarious, contentious, and dangerous world. Because this is the real world, where salvation needs to happen. For three centuries now, the tribes of Israel have lived in this hill country of Canaan. They’re holding on, barely. They are pressed from all sides, and battling within. They’re struggling to stay faithful to God. -

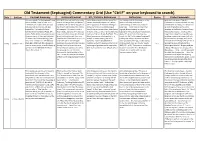

Old Testament

Old Testament (Septuagint) Commentary Grid (Use "Ctrl F" on your keyboard to search) Date Lection Content Summary Historical Context NT / Patristic References Reflections Psalm Psalm Comments The same words, "In the beginning" open Of 1.26 ("Then God said, 'Let us make Father Andrew points out that one of the The Fathers read the first chapters of the Basil the Great writes: "Like the the OT and the Gospel of John. In 1.2, man in our image, after our likeness") reasons these early chapters of Genesis Bible as unfolding a theological foundation in a house, the keel in a ship, "The earth was without form and void, Diadochus sets out the strong view of are so significant for Christian theology is understanding of the human condition and the heart in a body, so is [Psalm 1 as and [covered in] darkness until God the Church Fathers about the history because of St Paul's understanding of [whereas] … much modern scholarship a] brief introduction to the whole created life." In Ancient Christian of humanity: "All men are made in Jesus Christ as the new Adam, since "for as regards [these chapters] as ancient structure of the Psalms. For when David Commentary on Scripture (ACCS), OT I, God's image; but to be in his likeness in Adam, all die, so also in Christ shall all be legends of limited theological value [Louth, intended to propose … to [those who p.xxxix, Father Andrew Louth, points out is granted only to those who through made alive" (1 Cor 15.22, 45, 47,49). -

A Faithless Father's Faithful Son 1 Samuel 14:1-23

A Faithless Father’s Faithful Son 1 Samuel 14:1-23 June 16, 2019 Sermon Questions 1. Pastor Jim stated, “Faith is always focused on God‟s Word?" What does he mean by that? 2. How was faith “focused on God‟s Word” put on display by Jonathan as he went into battle? What evidence do you read in 1 Samuel to describe that type of faith? 3. What was the difference in belief system between Jonathan and Saul? 4. “We live under the shadows of Adam‟s sin,” noted Pastor Jim, similar to how Jonathan lived under the shadows of Saul‟s sin. How are you to think about that in your Christian walk? 5. Pastor Jim said, "God is for us. God is on our side." How do you reconcile that truth when bad things are happening to you? 6. Saul‟s sin had tragic consequences for Jonathan. Are Christians doomed if they have fathers or parents similar to Saul? Explain. 1 Samuel 14:1-23 (ESV) 14 One day Jonathan the son of Saul said to the young man who carried his armor, “Come, let us go over to the Philistine garrison on the other side.” But he did not tell his father. 2 Saul was staying in the outskirts of Gibeah in the pomegranate cave[a] at Migron. The people who were with him were about six hundred men, 3 including Ahijah the son of Ahitub, Ichabod's brother, son of Phinehas, son of Eli, the priest of the Lord in Shiloh, wearing an ephod. And the people did not know that Jonathan had gone. -

Additions Or Omissions in the Books of Samuel: the Significant Pluses and Minuses in the Massoretic, LXX and Qumran Texts

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 1984 Additions or Omissions in the Books of Samuel: The Significant Pluses and Minuses in the Massoretic, LXX and Qumran Texts Pisano, Stephen Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-151878 Monograph Published Version Originally published at: Pisano, Stephen (1984). Additions or Omissions in the Books of Samuel: The Significant Pluses and Minuses in the Massoretic, LXX and Qumran Texts. Freiburg, Switzerland / Göttingen, Germany: Universitätsverlag / Vandenhoeck Ruprecht. PISANO · ADDITIONS OR OMISSIONS IN THE BOOKS OF SAMUEL ORBIS BIBLICUS ET ORIENT ALIS Published by the Biblical Institute of the University of Fribourg Switzerland the Seminar für Biblische Zeitgeschichte of the University of Münster i. W. Federal Republic of Germany and the Schweizerische Gesellschaft für orientalische Altertumswissenschaft Editor: Othmar Keel Coeditors: Erich Zenger and Albert de Pury The Author: Stephen Pisano, S. J., received his Bachelor of Arts degree from Gonzaga Univer sity, Spokane (U.S.A.), in 1968. He studied theology at the Faculte de Theologie de Lyon-Fourviere from 1972 until 1974 and then at the Theology Faculty of Centre Sevres, Paris, from 1974 to 1976. He was awarded the Maitrise en Theologie (S.T.L.) in 1976. From 1976 until 1978 he studied at the Pontifical Biblical Ins titute in Rome, from which he received the Licentiate in Sacred Scripture (S.S.L.). After further research at the Biblical Institute during 1979-1980 he began doctoral studies at the University of Fribourg in 1980 and defended his thesis before the Theology Faculty of that university in 1982. -

7:2 Day 1 – Read I Samuel 4:1B

Lesson 3 IMPACT BIBLE STUDY DISCUSSION QUESTIONS I SAMUEL 4:1b – 7:2 Day 1 – Read I Samuel 4:1b – 7:2 1. What part of the lecture on I Samuel 2:11 – 4:1a was most significant to you? 2. The ark of the covenant is the subject of this week’s section of Scripture. See Exodus 25:1-22 for a description of the ark. a. Where was it to be kept? b. What were its dimensions? (a cubit is approximately 18”) c. What promise did God make concerning His presence? 3. What different titles are given to the ark? (7) Give the verse where each is first mentioned. 4. Give the movements of the ark from town to town. 5. How much time is noted to elapse? Give verses. 6. Was Samuel consulted concerning these decisions? Day 2 – Review I Samuel 4:1b – 22 7. Who decided to bring the ark from the tabernacle at Shiloh? 8. Who else was involved? 9. By the ark not being in its place, how do you think the life of the tabernacle was affected? 10. How did the Philistines respond when the ark came into camp? 11. From previous lessons and from Psalm 78:56-61 and Deuteronomy 28:15, 25, what was the basic cause of Israel’s defeat? 12. a. What verse from a previous lesson was fulfilled in verse 11? b. What attribute of God does this show? (See II Peter 3:9) 13. a. What was the message the man of Benjamin brought to Eli? b. -

Sermon Notes

Dawn of a Kingdom 1 Samuel 1 Samuel 14:1-23 To Boldly Go 1 Samuel 14:1-3 (ESV) 1 One day Jonathan the son of Saul said to the young man who carried his armor, “Come, let us go over to the Philistine garrison on the other side.” But he did not tell his father. 2 Saul was staying in the outskirts of Gibeah in the pomegranate cave at Migron. The people who were with him were about six hundred men, 3 including Ahijah the son of Ahitub, Ichabod’s brother, son of Phinehas, son of Eli, the priest of the LORD in Shiloh, wearing an ephod. And the people did not know that Jonathan had gone. 1 Samuel 14:6-17 (ESV) 6 Jonathan said to the young man who carried his armor, “Come, let us go over to the garrison of these uncircumcised. It may be that the LORD will work for us, for nothing can hinder the LORD from saving by many or by few.” 7 And his armor-bearer said to him, “Do all that is in your heart. Do as you wish. Behold, I am with you heart and soul.” 8 Then Jonathan said, “Behold, we will cross over to the men, and we will show ourselves to them. 1 Samuel 14:1-23 To Boldly Go 1 Samuel 14:6-17 (ESV) 9 If they say to us, ‘Wait until we come to you,’ then we will stand still in our place, and we will not go up to them. 10 But if they say, ‘Come up to us,’ then we will go up, for the LORD has given them into our hand. -

Download Slides

Ichabod “We believe that God has graciously disclosed his existence and power in creation and has supremely revealed himself in the person of his Son, the incarnate Word. God has also revealed himself in his written Word, the verbally inspired sixty-six books of the Old and New Testaments. It is complete in its revelation of his will for salvation, sufficient for all that God requires us to believe and do, and final in its authority over every domain of knowledge to which it speaks. The Bible is to be believed, as God’s perfect instruction, in all that it teaches; obeyed, as God’s command, in all that it requires; and trusted, as God’s pledge, in all that it promises.” 1 Samuel 4:1b-2(ESV) Now Israel went out to battle against the Philistines. They encamped at Ebenezer, and the Philistines encamped at Aphek. 2 The Philistines drew up in line against Israel, and when the battle spread, 1 Samuel 4:1b-2(ESV) Israel was defeated before the Philistines, who killed about four thousand men on the field of battle. 1 Samuel 4:3-4 (ESV) And when the people came to the camp, the elders of Israel said, “Why has the LORD defeated us today before the Philistines? Let us bring the ark of the covenant of the LORD here from Shiloh, that it may come among us and save us from the power of our enemies.” 1 Samuel 4:3-4 (ESV) 4 So the people sent to Shiloh and brought from there the ark of the covenant of the LORD of hosts, who is enthroned on the cherubim. -

Samuel I Samuel 1:1- 9:2 September 19, 2019

1 DAVID A MAN AFTER GOD’S OWN HEART Pastor’s Bible Study 2019 By Dr. Bob Fuller Episode 2: Samuel I Samuel 1:1- 9:2 September 19, 2019 • The Bible portrays Samuel in a variety of roles: priest, prophet, judge, and “seer.” The role with which the greatest number of scholars associate the historical Samuel is that of judge. 1 Sam 7:15 declares that “Samuel judged Israel all the days of his life.” • The name “Samuel” means “Heard of God” or “Name of God.” I. THE STORY OF HANNAH (1:1-2:11, 18-21, 26) A. Her miraculous son (1:19-28; 2:11, 18-20, 26): The Lord honors Hannah's request, and she gives birth to Samuel. Hannah dedicates Samuel to the Lord and leaves him at the Tabernacle after he is weaned. She visits Samuel yearly, making a coat for him each year and watching him grow. B. Her song (2: 1-11): In this remarkable prayer, Hannah praises the Lord for his holiness, his omniscience, his sovereignty, his compassion, and his justice. II. THE FAMILY OF ELI (2:12-17, 22-25, 27-36): Eli the priest has two wicked sons, Hophni and Phinehas. A. Their wickedness (2:12-17, 22) 1. They are guilty of impiety (2:12, 17) 2. They are guilty of intimidation (2: 13-16). 3. They are guilty of immorality (2:22). B. Their warning (2:23-25, 27-36) 1. From the parent (2:23-25): Eli attempts to correct his rebellious sons, but it is too late. -

Intro Biblical Background from the Passage We Learn Eli's Daughter In

Intro Ichabod! Why give this chapter the title 'Ichabod' you ask? Well, do you remember the story from a dark passage in Israel’s history, when the Philistines battled against Israel and took the Ark of the Covenant? Biblical Background 5 As the ark of the covenant of the LORD came into the camp, all Israel shouted with a great shout, so that the earth resounded. 6 When the Philistines heard the noise of the shout, they said, “What does the noise of this great shout in the camp of the Hebrews mean?” Then they understood that the ark of the LORD had come into the camp. 7” 1 Samuel 4:5-7 “ So the Philistines fought and Israel was [c]defeated, and every man fled to his tent; and the slaughter was very great, for there fell of Israel thirty thousand foot soldiers. 11 And the ark of God was taken; and the two sons of Eli, Hophni and Phinehas, died.” 1 Samuel 4:10 “When he mentioned the ark of God, [f]Eli fell off the seat backward beside the gate, and his neck was broken and he died, for [g]he was old and heavy. Thus he judged Israel forty years.” 1 Samuel 4:10 “Now his daughter-in-law, Phinehas’s wife, was pregnant and about to give birth; and when she heard the news that the ark of God was taken and that her father-in-law and her husband had died, she kneeled down and gave birth, for her pains came upon her. 20 And about the time of her death the women who stood by her said to her, “Do not be afraid, for you have given birth to a son.” But she did not answer or pay attention. -

First and Second Samuel

VOLUME 8 OLD TESTAMENT NEW COLLEGEVILLE THE BIBLE COMMENTARY FIRST AND SECOND SAMUEL Feidhlimidh T. Magennis SERIES EDITOR Daniel Durken, O.S.B. LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Nihil Obstat: Reverend Robert C. Harren, J.C.L., Censor deputatus. Imprimatur: W Most Reverend John F. Kinney, J.C.D., D.D., Bishop of St. Cloud, Minnesota, October 14, 2011. Design by Ann Blattner. Cover illustration: David Anthology by Donald Jackson. Copyright 2010 The Saint John’s Bible, Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota USA. Used by permis- sion. Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, Catholic Edition, copyright 1989, 1993 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All right reserved. Photos: pages 10, 121, 142, Thinkstock.com; pages 53, 72, 103, 111, Wikimedia Commons. Maps created by Robert Cronan of Lucidity Information Design, LLC. Scripture texts used in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edi- tion © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc., Washington, DC. All Rights Reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. © 2012 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, micro fiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, P.O.