“See with Eyes Unclouded”: Mononoke-Hime As the Tragedy of Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Girlhood Reimagined: Representations of Girlhood in the Films of Hayao Miyazaki

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Karissa Sabine for the degree of Master of Arts in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies presented on June 8, 2017. Title: Girlhood Reimagined: Representations of Girlhood in the Films of Hayao Miyazaki. Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ Bradley Boovy Despite the now common usage of the term “girl”, there has been little call for pause and deeper analysis into what we actually mean when we use this term. In particular, animated film provides a wide scope of media texts that claim to focus on girlhood; but how do we in fact know girlhood? How is girlhood constructed? With these questions in mind, I use feminist textual analysis to examine three films— Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), and Princess Mononoke (1997)—by acclaimed Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki in which girl characters and girlhood play prominently into the film's construction as a whole. In particular, I examine how Miyazaki constructs girlhood through his storylines and characters and how these characters (i.e. girls) are then positioned in relation to three specific aspects of their representation: their use of clothing, their relationships to other characters, and their freedom of movement relative to other characters. In doing so, I deconstruct more traditionally held notions of girlhood in which girls are seen as dependent and lacking autonomy. Through Miyazaki’s work, I instead offer up a counternarrative of girlhood in which the very category of gender, and indeed “girls”, are destabilized. In doing so, I hope to provide a wider breadth of individuals the chance to see themselves represented in animated film in both significant and meaningful ways. -

Spirited Away Study Guide

Spirited Away Directed by Hayao Miyazki This study guide suggests cross-curricular activities based on the film Spirited Away by Hanoko Miyazaki. The activities seek to complement and extend the enjoyment of watching the film, while at the same time meeting some of the requirements of the National Curriculum and Scottish Guidelines. The subject area the study guide covers includes Art and Design, Music, English, Citizenship, People in Society, Geography and People and Places. The table below specifies the areas of the curriculum that the activities cover National Curriculum Scottish Guidelines Subject Level Subject Level Animation Art +Design KS2 2 C Art + Investigating Visually and 3 A+B Design Reading 5 A-D Using Media – Level B-E Communicating Level A Evaluating/Appreciating Level D Sound Music KS2 3 A Music Investigating: exploring 4A-D sound Level A-C Evaluating/Appreciating Level A,C,D Setting & English KS2 Reading English Reading Characters 2 A-D Awareness of genre 4 C-I Level B-D Knowledge about language level C-D Setting & Citizenship KS2 1 A-C People People & Needs in Characters 4 A+B In Society Society Level A Japan Geography KS2 2 E-F People & Human Environment 3 A-G Places Level A-B 5 A-B Human Physical 7 C Interaction Level A-D Synopsis When we first meet ten year-old Chihiro she is unhappy about moving to a new town with her parents and leaving her old life behind. She is moody, whiney and miserable. On the way to their new house, the family get lost and find themselves in a deserted amusement park, which is actually a mythical world. -

How the Filmography of Hayao Miyazaki Subverts Nation Branding and Soft Power

View metadata, citation and similarbrought COREpapers to youat core.ac.ukby provided by University of Tasmania Open Access Repository 1 Wings and Freedom, Spirit and Self: How the Filmography of Hayao Miyazaki Subverts Nation Branding and Soft Power Shadow (BA Hons) 195408 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Journalism, Media and Communications University of Tasmania June, 2015 2 Declaration of Originality: This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of the my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. X Shadow Date: 6/10/2015 Authority of Access: This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. X Shadow Date: 6/10/2015 3 Declaration of Copy Editing: Professional copy was provided by Walter Leggett to amend issues with consistency, spelling and grammar. No other content was altered by Mr Leggett and editing was undertaken under the consent and recommendation of candidate’s supervisors. X Shadow Date: 6/10/2015 4 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1 ............................................................................................................................. -

Japanese Film and Culture Special Screening Evenings

Japanese Film and Culture Special screening evenings Date: 28 March & 9 May 2014 Time: 5.30pm- Place: Andrew Stewart Cinema, Gilmorehill Halls, 9 University Avenue, Glasgow G12 8QQ Programme: Welcome and introduction: Dr Saeko Yazaki Screening: Princess Mononoke (28 Mar) / Departures (9 May) [Japanese with English subtitles] Discussion and Q&A: Dr Yazaki with Dr Rob Maslen (28 Mar) / Dr Charlie Orzech (9 May) Followed by refreshments with sushi You are warmly invited to join us for these two special Japanese film evenings. Funded by the School of Critical Studies, Glasgow University, the events will highlight a range of key issues in Japanese tradition raised by each of our films, with special reference to the cultural background and translation issues they invoke. Princess Mononoke (もののけ姫), 1997, PG13, 134min; animation Director: Hayao Miyazaki While protecting his village from a rampaging boar-god/demon, a confident young warrior, Ashitaka, is stricken by a deadly curse. To save his life, he must journey to the forests of the west, where the ambitious Lady Eboshi and her loyal clan wage war with the gods of the forest, who are aided by a brave young woman, Princess Mononoke. Ashitaka sees the good in both sides and tries to stem the flow of blood. (Adapted from IMDb website) Departures (おくりびと), 2008, PG13, 130min Director: Yojiro Takita Daigo Kobayashi is a devoted cellist in an orchestra that has just been dissolved and now finds himself without a job. He answers a classified ad entitled "Departures", thinking it is an advertisement for a travel agency, only to discover that the job is actually for a ‘Nokanshi’ or ‘encoffineer’, a funeral professional who prepares deceased bodies for burial and entry into the next life. -

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: a Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’S Monster Princess

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: A Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 25–40. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 01:01 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 25 Chapter 1 P RINCESS MONONOKE : A GAME CHANGER Shiro Yoshioka If we were to do an overview of the life and works of Hayao Miyazaki, there would be several decisive moments where his agenda for fi lmmaking changed signifi cantly, along with how his fi lms and himself have been treated by the general public and critics in Japan. Among these, Mononokehime ( Princess Mononoke , 1997) and the period leading up to it from the early 1990s, as I argue in this chapter, had a great impact on the rest of Miyazaki’s career. In the fi rst section of this chapter, I discuss how Miyazaki grew sceptical about the style of his fi lmmaking as a result of cataclysmic changes in the political and social situation both in and outside Japan; in essence, he questioned his production of entertainment fi lms featuring adventures with (pseudo- )European settings, and began to look for something more ‘substantial’. Th e result was a grave and complex story about civilization set in medieval Japan, which was based on aca- demic discourses on Japanese history, culture and identity. -

"Deer Gods, Nativism and History: Mythical and Archaeological Layers in Princess Mononoke." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’S Monster Princess

Niskanen, Eija. "Deer Gods, Nativism and History: Mythical and Archaeological Layers in Princess Mononoke." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 41–56. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 8 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 8 October 2021, 10:51 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. Released under a CC BY-NC-ND licence (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 41 Chapter 2 D EER GODS, NATIVISM AND HISTORY: MYTHICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL LAYERS IN PRINCESS MONONOKE E i j a N i s k a n e n I n Mononokehime ( Princess Mononoke , 1997) Hayao Miyazaki depicts the main character, Prince Ashitaka, as a son of the Emishi nation, one of Japan’s van- ished native tribes, who inhabited West- Northern Japan before the Eastern- Southern Yamato nation took control, starting in the area that is now the basis for modern Japan before claiming the entire country. Emishi, similar to the other native tribes of Northern Japan are oft en seen as non- civilized barbar- ians as opposed to the Yamato race. 1 Th ough Princess Mononoke is set in the Muromachi period (1333– 1573), when the Yamato society had conquered all the Northern tribes, the strong Emishi village of Princess Mononoke recalls Japan’s pre- historic times. In the fi lm’s settings and details one can fi nd numer- ous examples of Miyazaki’s interest in anthropology, archaeology, Shint ō and nativism. -

Elements of Realism in Japanese Animation Thesis Presented In

Elements of Realism in Japanese Animation Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By George Andrew Stey Graduate Program in East Asian Studies The Ohio State University 2009 Thesis Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance, Advisor Professor Maureen Hildegarde Donovan Professor Philip C. Brown Copyright by George Andrew Stey 2009 Abstract Certain works of Japanese animation appear to strive to approach reality, showing elements of realism in the visuals as well as the narrative, yet theories of film realism have not often been applied to animation. The goal of this thesis is to systematically isolate the various elements of realism in Japanese animation. This is pursued by focusing on the effect that film produces on the viewer and employing Roland Barthes‟ theory of the reality effect, which gives the viewer the sense of mimicking the surface appearance of the world, and Michel Foucault‟s theory of the truth effect, which is produced when filmic representations agree with the viewer‟s conception of the real world. Three directors‟ works are analyzed using this methodology: Kon Satoshi, Oshii Mamoru, and Miyazaki Hayao. It is argued based on the analysis of these directors‟ works in this study that reality effects arise in the visuals of films, and truth effects emerge from the narratives. Furthermore, the results show detailed settings to be a reality effect common to all the directors, and the portrayal of real-world problems and issues to be a truth effect shared among all. As such, the results suggest that these are common elements of realism found in the art of Japanese animation. -

"Introducing Studio Ghibli's Monster Princess: from Mononokehime To

Denison, Rayna. "Introducing Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess: From Mononokehime to Princess Mononoke." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 1–20. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 6 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 6 October 2021, 08:10 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 I NTRODUCING STUDIO GHIBLI’S MONSTER PRINCESS: FROM M ONONOKEHIME TO P RINCESS MONONOKE Rayna Denison When it came out in 1997, Hayao Miyazaki’s Mononokehime ( Princess Mononoke ) was a new kind of anime fi lm. It broke long- standing Japanese box offi ce records that had been set by Hollywood fi lms, and in becoming a blockbuster- sized hit Mononokehime demonstrated the commercial power of anime in Japan.1 F u r t h e r , Mononokehime became the fi rst of Miyazaki’s fi lms to benefi t from a ‘global’ release thanks to a new distribution deal between Disney and Tokuma shoten, then the parent company for Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli. As a result of this deal, Mononokehime was transformed through translation: US star voices replaced those of Japanese actors, a new market- ing campaign reframed the fi lm for US audiences and famous fantasy author Neil Gaiman undertook a localization project to turn Mononokehime into Princess Mononoke (1999). 2 A s Princess Mononoke, it was the fi rst Miyazaki fi lm to receive a signifi cant cinematic release in the United States. -

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness

A Film by Mami Sunada THE KINGDOM OF DREAMS AND MADNESS A look inside the fantastically mad world of the people behind Studio Ghibli PRESENTED BY Dwango IN COOPERATION WITH Studio Ghibli PRODUCED BY Nobuo Kawakami WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY Mami Sunada MUSIC BY Masakatsu Takagi PRODUCTION COMPANY ENNET Technical Specification FORMAT Digital ASPECT RATIO 1920 x 1080 SOUND 5.1ch COLOR Color RUNNING TIME 118 minutes LANGUAGE Japanese with subtitles PRODUCTION YEAR 2013 COPYRIGHT NOTICE © 2013 dwango ABOUT THE FILM There have been numerous documentaries about Studio Ghibli made for television and for DVD features, but no one had ever conceived of making a theatrical documentary feature about the famed animation studio. That is precisely what filmmaker Mami Sunada set out to do in her first film since her acclaimed directorial debut, Death of a Japanese Salesman. With near-unfettered access inside the studio, Sunada follows the key personnel at Ghibli – director Hayao Miyazaki, producer Toshio Suzuki and the elusive “other” director, Isao Takahata – over the course of approximately one year as the studio rushes to complete their two highly anticipated new films, Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises and Takahata’s The Tale of The Princess Kaguya. The result is a rare glimpse into the inner workings of one of the most celebrated animation studios in the world, and a portrait of their dreams, passion and dedication that borders on madness. DIRECTOR: MAMI SUNADA Born in 1978, Mami Sunada studied documentary filmmaking while at Keio University before apprenticing as a director’s assistant under Hirokazu Kore-eda and others. -

Anime and Historical Inversion in Miyazaki Hayao's Princess

Anime and Historical Inversion in Miyazaki Hayao’s Princess Mononoke John A. Tucker East Carolina University Introduction If box office receipts are any indication of cultural significance, then Miyazaki Hayao’s Princess Mononoke (Mononokehime, 1997) surely stands as one of the most important works of late-twentieth-century Japanese popular culture: currently it remains the highest-grossing (¥16.65 billion, approximately $150 million) domestic film in Japanese history. Prior to the release of The Titanic, Princess Mononoke eclipsed E.T. and reigned as the biggest box-office hit ever, domestic or foreign, in Japan. While The Titanic has since surpassed Princess Mononoke in overall ticket sales, over 13.53 million Japanese, or more than one-tenth of the population, have watched Princess Mononoke in theatres, and over five million copies of the video have been sold domestically (Yoneda, 204). Princess Mononoke also stands as the most expensive animated movie ever made in Japan, with a 3 billion yen (approximately $30 million) production cost (Wakita et al., 168). Critics have lauded it in literally hundreds of media reviews, especially in Japanese film and popular culture publications such as Kinema junpō, SAPIO, Nyūmedeia, AERA, uirumumeekaazu, Bessatsu Comicbox, Bessatsu Takarajima, Tech Win, Shunkan Kinyōbi, Video Doo!, Yurika, Cinema Talk, and SPA!, as well as in the major newspapers, periodicals, and regional media. Additionally, Princess Mononoke has been awarded numerous prizes, most notably the 21st Japan Academy Award for Best Film (Kuji, 3-4; Schilling, 3). Not surprisingly the film has been released internationally, with an English language version, featuring numerous familiar American voices, including that of Gillian Anderson and Billy Bob Thornton, thus making it exceptionally accessible in the United States for anime fans, and those interested in Japanese history and culture. -

Language Lab Video Catalog

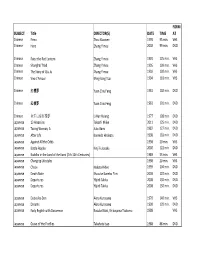

FORM SUBJECT Title DIRECTOR(S) DATE TIME AT Chinese Ermo Zhou Xiaowen 1995 95 min. VHS Chinese Hero Zhang Yimou 2002 99 min. DVD Chinese Raise the Red Lantern Zhang Yimou 1991 125 min. VHS Chinese Shanghai Triad Zhang Yimou 1995 109 min. VHS Chinese The Story of Qiu Ju Zhang Yimou 1992 100 min. VHS Chinese Vive L'Amour Ming‐liang Tsai 1994 118 min. VHS Chinese 紅樓夢 Yuan Chiu Feng 1961 102 min. DVD Chinese 紅樓夢 Yuan Chiu Feng 1961 101 min. DVD Chinese 金玉良緣紅樓夢 Li Han Hsiang 1977 108 min. DVD Japanese 13 Assassins Takashi Miike 2011 125 min. DVD Japanese Taxing Woman, AJuzo Itami 1987 127 min. DVD Japanese After Life Koreeda Hirokazu 1998 118 min. DVD Japanese Against All the Odds 1998 20 min. VHS Japanese Battle Royale Kinji Fukasaku 2000 122 min. DVD Japanese Buddha in the Land of the Kami (7th‐12th Centuries) 1989 53 min. VHS Japanese Changing Lifestyles 1998 20 min. VHS Japanese Chaos Nakata Hideo 1999 104 min. DVD Japanese Death Note Shusuke Kaneko Film 2003 120 min. DVD Japanese Departures Yôjirô Takita 2008 130 min. DVD Japanese Departures Yôjirô Takita 2008 130 min. DVD Japanese Dodes'ka‐Den Akira Kurosawa 1970 140 min. VHS Japanese Dreams Akira Kurosawa 1990 120 min. DVD Japanese Early English with Doraemon Kusuba Kôzô, Shibayama Tsutomu 1988 VHS Japanese Grave of the Fireflies Takahata Isao 1988 88 min. DVD FORM SUBJECT Title DIRECTOR(S) DATE TIME AT Japanese Happiness of the Katakuris Takashi Miike 2001 113 min. DVD Japanese Ikiru Akira Kurosawa 1952 143 min. -

Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’S Monster Princess

Nicholson, Jennifer E. "The Translation and Adaptation of Miyazaki’s Spirit Princess in the West." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 133–150. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 21:10 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 33 Chapter 7 T HE TRANSLATION AND ADAPTATION OF MIYAZAKI’S SPIRIT PRINCESS IN THE WEST Jennifer E. Nicholson In 2009, 10 years aft er the Miramax release of Princess Mononoke in dubbed English, author Neil Gaiman was interviewed about a particularly interesting aspect of his involvement in the translation project. When interviewer Steve Biodrowski mentioned ‘ issues with Miramax’ about word choices in the trans- lation, Gaiman responded that they ‘got to keep “samurai,” ’ which had at once point been ‘warrior’, but that their script ‘lost “sake”; “sake” became “wine.” ’1 Th e word is used in passing, once, in the scene where the Lady Eboshi apolo- gises to the men making rifl es, and promises to ‘have wine sent down later’. If the script had used sake instead, what would change? At fi rst glance, any anxiety about the word’s translation seems unnecessary. While sake is a particular kind of rice wine, diff erent to ‘wine’ in the way the word is more commonly used in English, Eboshi’s off er remains equivalent across the two languages: she will make sure they receive a drink aft er their work is done.