THE ART of SHOOTING the Life and Times of Arthur C. Jackson Being

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Camper's Own Book

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 0DDD4DSS4flE ,^o\.-^..r^ ''J-^ ^ ^°-n».. t* ^0 rT.-' ,0 .^'\ ^'^^ ^'^^^^: yO^^, • <3Lr vS^-' V ^^<^- L- "^ : "^^^^ .^^^<^ \. ,c°/i^;.'>- /.v:^-''-^^ c°^'i^'.^'l Sheen will tarnish, honey cloy, And merry is only a mask of sad, But, sober on a fund of joy, The ivoods at heart are glad. The black ducks mounting from the lake. The pigeon in the pines, The bittern's boom, a desert make Which no false art refines. Emersox: Waldeinsamkeit. s o UJ ^ < a, -J >> -^ I o The Camper's Own Book A Handy Volume for Devotees of Tent and Trail With Contributions by Stewart Edward White F. C. Selous Tarleton Bean J. Horace McFarland Edward Breck A. K. P. Harvey George Gladden Henry Oldvs Charles Bradford J. W. Elwood Ernest Ingersoll Frank A. Bates and Other Authorities Compiled and Edited by :}E0RGE sf' BRYAN Canadian Camp Club New York THE LOG CABIN PRESS 1912 0^ %^V' Copyright, 1912, by THE LOG CABIN PRESS C1.A314G84 J ri Table of Contents PAGE REFACE 5 [^Peoeogue : The Benefits of Recreation .... 7 By L. E. Eubanks I The Camp-Fire 9 By William C. Gray "Horse Sense" in the Woods. 13 By Stewart Edward White Comfort in Camp 20 By Frank A. Bates Outfits 26 Suggestions for the Sportsman's Outfit. 31 By A. K. P. Harvey Suggestions for Hunting Outfits 35 By Townsend Whelen Grub Lists 43 Canoes and Canoeing 48 By Edward Breck Animal Packing 52 By Charles H. Stoddard What To Do If Lost 59 By Frank A. Bates The Black Bass and His Ways 62 By Tarleton Bean About Fly-Fishing for Brook-Trout 69 By Charles Bradford Pointers for Anglers 76 By Charles Bradford The Rifle in the Woods 81 By George Gladden PAGE Hunting Caribou in Newfoundland 96 By F. -

AUSTRALIAN $8.95 Incl

Hall of Fame accolade for Paralympic great September 2020 AUSTRALIAN $8.95 incl. GST ShooterTHE MAGAZINE FOR SPORTING SHOOTERS FABARM’S fabulous five-shot Will the REAL 38 PLEASE STAND UP! Howa ‘mini-me’ a MAXI ATTRACTION REVIEWS Smart device puts you in the picture / Predator AF 10x42 binoculars Mark van den Boogaart’s favourite rifle/cartridge/scope The official publication of the Sporting Shooters’ Association of Australia Now 199,500+ members strong! Proudly printed in Australia ssaa.org.au Australian Standard AS/NZS 1337.1 Certified RX inserts available for Prescriptions BALLISTIC RATED Polarised options available IMPACT PROTECTION WX VALOR CHANGEABLE WX VAPOR CHANGEABLE SINGLE LENS, 2 LENS & 3 LENS KITS AVAILABLE CHANGEABLE SERIES 2 & 3 LENS KITS AVAILABLE POLARISED AND NON POLARISED LENS OPTIONS FITS RX PRESCRIPTION INSERT AS/NZS 1337.1:2010 CERTIFIED AS/NZS 1337.1:2010 CERTIFIED WX GRAVITY RX INSERT PTX SPECIFICATIONS ACTIVE WX OMEGA REMOVABLE ULTRA POLARISED AND NON POLARISED LENS OPTIONS FOAM™ GASKET TO BLOCK OUT WIND, DOUBLE INJECTED TEMPLE TIPS AS/NZS 1337.1:2010 CERTIFIED WileyXDUST AND DEBRIS VAPOR is official issue to theFOR ADDEDAustralian STABILITY Defence Force CLIMATE CONTROL WX SABER ADVANCED CHANGEABLE WX GRAVITY INCLUDES REMOVABLE GASKET TO BLOCK OUT WIND DUST & DEBRIS SMOKE GREY, CLEAR AND LIGHT RUST LENS KITS ALSO AVAILABLE RX CAPABLE INCLUDESFOIL™ ANTI-FOG ELASTIC COATING STRAP AND LEASH CORD FITS RX PRESCRIPTION INSERT AS/NZS 1337.1:2010 CERTIFIED AS/NZS 1337.1:2010 CERTIFIED RX INSERT PTX INTERCHANGEABLE LENS -

The History of the Pan American Games

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1964 The iH story of the Pan American Games. Curtis Ray Emery Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Emery, Curtis Ray, "The iH story of the Pan American Games." (1964). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 977. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/977 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 65—3376 microfilmed exactly as received EMERY, Curtis Ray, 1917- THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES. Louisiana State University, Ed.D., 1964 Education, physical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education m The Department of Health, Physical, and Recreation Education by Curtis Ray Emery B. S. , Kansas State Teachers College, 1947 M. S ., Louisiana State University, 1948 M. Ed. , University of Arkansas, 1962 August, 1964 PLEASE NOTE: Illustrations are not original copy. These pages tend to "curl". Filmed in the best possible way. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, INC. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study could not have been completed without the close co operation and assistance of many individuals who gave freely of their time. -

The Roaring Twenties”, SSUSA, February 2015

MORE WOMEN COACHES | ALL-AMERICAN AWARDS | GUNS OF THE 1920s FEBRUARY 2015 | VOL. 28 NO. 2 SPOR TS NRA’S COMPETITIVE SHOOTING JOURNAL LL MERICAN NRA PROGRAM The Exclusive Precious Metals & Rare Coin Expert of NRA Publications SPECIAL NRA MEMBER OFFER JUSTJUST releASeDreleASeD 20152015 gOlDgOlD && SilverSilver AmericAnAmericAn eAgleSeAgleS ROLL OVER YOUR IRA OR 401K TO A GOLD IRA TODAY B 3 EASY STEPS 444 1. CREATE AN ACCOUNT 2. TRANSFER FUNDS 3. BUILD YOUR PORTFOLIO. 2015 $50 Gold American Eagles • 1oz Gold Order gem Brilliant Uncirculated Strictly limited inventory Offer IRA 2015 $1 Silver American eagles now IRA With the potential for sales halts from By special invitation, you are eligible to the U.S. Mint like in 2014, inventory, ELIGIBLE secure some of the earliest releases of 2015 ELIGIBLE pricing, and availability are not guaranteed. Silver American Eagles from First Fidelity Demand for gold and silver newly released 1 % products from the U.S. Mint in recent 2 Reserve.® We expect an overwhelming / response and have secured a substantial but years have put dealers, investors and * Over Spot Price limited inventory and will be processing all collectors on high-alert and resulted in transactions in the order they are received. $ 50 overwhelming demand. 4 or LESS Over Spot * Avoid Silver Sellout - Secure Today Spot Price x .045 (or less) + Spot Price = Cost per coin U.S. mint new release Price each Since 1986, the first year of their issue, the 3 We cannot guarantee inventory to satisfy Example: ($1200 x .045) + $1200 = $1254 Silver American Eagle series has established Plus Priority Shipping & Insurance demand so ORDERS WILL BE PROCESSED Call for current pricing itself as the most popular series of legal Limit 5 per household STRICTLY IN THE ORDER THEY ARE Plus Express Shipping & Insurance tender silver coins ever minted in United Check or Money Order RECEIVED.Place your order today to secure Limit 10 per household • Availability not guaranteed States history. -

October 2019 Auction No

Australian Arms Auctions Auctions Arms Australian 198 214 230 234 261 Australian Arms Auctions Auction No. 53 October 13th, 2019 13th, October 53 No. Auction Auction No. 53 October 13th, 2019 Melbourne 9 10 12 22 23 26 41 46 53 54 55 58 59 61 presenting our October 2019 Auction No. 53 Sunday 13th October at 10.00 am VIEWING: Saturday 12 noon to 5 pm & Sunday 8 am to 10 am Auctioneer: Harry Glenn HUNGARIAN COMMUNITY CENTRE 760 Boronia Road Wantirna 3152 Melway 63 F-5 Excellent onsite parking facilities available. Café available by Cheryl Savage. Try the Sunday breakfast Contacts: Roland Martyn: 0428 54 33 77 Cheryl Martyn Admin: (61) 03 9848 7951 P.O. Box 1142 Doncaster East Vic 3109 Email: [email protected] www.australianarmsauctions.com 15 % Buyers Premium + GST applies. Plus GST to any lots where indicated 1 L/R = Licence required in the State of Victoria. ALL ESTIMATES IN AUSTRALIAN DOLLARS. 1 JAPANESE TYPE 30 ARISAKA CARBINE: 6.5 Arisaka; 5 shot box mag; 18.2" barrel; f. bore; standard sights, $800 - 900 bayonet stud, sling swivels, Japanese characters & chrysanthemum; vg profiles & clear markings; 85% original military finish remaining to barrel, receiver & fittings; vg stock with minor bruising; all complete including bolt dust cover but screw missing from butt plate; no cleaning rod; gwo & vg cond. #612776 matching bolt L/R 2 JAPANESE TYPE 99 ARISAKA SHORT RIFLE: 7.7 Arisaka; 5 shot box mag; 25.2" barrel; f to g bore; standard $700 - 900 sights, bayonet stud & monopod; Japanese characters to the breech, Imperial crest removed; vg profiles & clear markings; 70% original military finish remains to barrel, receiver & fittings; vg stock with minor bruising; complete with rod, swivels & dust cover to bolt; missing 2 nose cap screws; gwo & cond. -

This Is Yours

fern 1i-30<f hWà 111 IM i :J i w ISSUE NQI APRIL* bl FREE TO SI'S PUBLISHED UNDERGROUND-FOR AND BY GPS AT THE FORT ORD MILITARY COMPLEX iiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiitiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiQiiiiiiiiiii A NEWSPAPER FOR SERVICEMEN THIS IS YOURS NO ONE CAN TAKE TMS AWAY FfcOAA YOU Travel TOUR #1 Quick Action-packed 12 Month THIS COPY IS YOUR, PRIVATE PROPERTY Trip to the Exotic and Exciting EVEU âl'S HAVE CONSTITUTIONAL rUSHTS FAR EAST (VIETNAM) TOUR #2 13 months in Korea TOUR #3 Hawaii - Japan • Okinawa TOUR #4 Hunt and Fish in Alaska T'RniK/IN^ 1)-RV TOUR #5 Serve in the Sunny Caribbean ) s/ ALL EXPENSES PAID For full details see your unit travel agent (RE-ENLISTMENT NCO) FOR M one i Hf». f4ii s.f. £Z/-Z/VZ r-uptight the brass MAKE RESERVATIONSTODAY Work togefh IIMTERVIE FLASH!, EN MONTEREY!! ! ! Interview with Mrs. Trecethen mother of Ernest Trefethen one i inselinq Center will be of the Presidio 27 .beina tried »round May 1, 69 .in 1 for "MUTINY ;! ! ! '. Monterey. It's pur pose will be to counsel GI's What we.s your soi'» sent to the on C Lcations. To direct stockade .'or: A.WGL, was serv to Legal, suirttural and ing a 6 month sentence. nsychiatriatic del:, with-in the What was your reaction to tha area. This is a cooo orwuect news of the protest? Well I was with local groups, and S.c\ never informed ny the Artnv, X sroups sending down ...ull tinte read about, it. îri the newspaoer. counselors, clercrvmen, What is your opinion of your •ers. -

October 2020

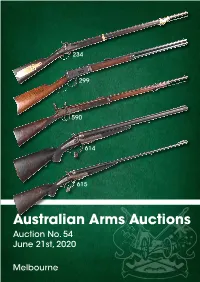

Australian Arms Auctions Auctions Arms Australian 234 299 590 614 615 Australian Arms Auctions Auction No. 54 June 21st, 2020 21st, June 54 No. Auction Auction No. 54 June 21st, 2020 Melbourne 343 342 353a 352a 353 346 presenting our Auction No. 54 Sunday 21st June 2020 at 10.00 am VIEWING: Saturday 12 noon to 5 pm & Sunday 8 am to 10 am Auctioneer: Harry Glenn HUNGARIAN COMMUNITY CENTRE 760 Boronia Road Wantirna 3152 Melway 63 F-5 Excellent onsite parking facilities available. Café available by Cheryl Savage. Try the Sunday breakfast Contacts: Roland Martyn: 0428 54 33 77 Cheryl Martyn Admin: (61) 03 9848 7951 P.O. Box 1142 Doncaster East Vic 3109 Email: [email protected] www.australianarmsauctions.com 15 % Buyers Premium + GST applies. Plus GST to any lots where indicated 1 L/R = Licence required in the State of Victoria. ALL ESTIMATES IN AUSTRALIAN DOLLARS. 1 B.S.A. MARTINI CADET RIFLE: 310 Cal; 25.2" barrel; g. bore; standard sights, swivels & front sight cover; $500 - 700 C of A markings to rhs of action & B.S.A. BIRMINGHAM & Trade mark to lhs; vg profiles & clear markings; blue finish to all metal; vg butt stock & forend with SA CMF markings to butt; gwo & vg cond. #47103 L/R 2 TURKISH ISSUE GER 88 B/A INFANTRY RIFLE: 7.92x57; 5 shot box mag; 28.25" barrel; g. bore; standard $600 - 700 sights, rod & swivels; breech with German Imperial crown AMBERG 1891; GEW 88 to side rail; g. profiles & clear markings; blue/black finish to barrel, bands, receiver & magazine; bolt in the white; g. -

Official Media Guide March 23 – April 1, 2012 Tucson Trap & Skeet Club 7800 W

12 US 20 A I S P SF U WORLD C OFFICIAl Media Guide March 23 – april 1, 2012 Tucson Trap & Skeet club 7800 W. Old ajo highway visitTucson.org 2012worldcup.tucsontrapandskeet.com (520) 883-6426 | toll free (888) 530-5335 COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. USA Shooting is pleased to introduce the official 2012 Media Guide for the Tucson World Cup. Since participation in the first Olympic Games in 1896, American shooters have won over 100 medals. Though the events have changed over the years, the spirit of the Games remains. The title of the media guide is “Creating Legends on the Road to London” because American shooters have been so successful in the past and the future is equally lustrous. While there are many opportunities to shoot competitively in the United States, USA Shooting offers world-class athletes the opportunity to achieve Olympic and Paralympic dreams. “To me, the concept of wearing the USA on my back in the Paralympic Games in 2012 means that I have found my way through the fear factor. I have found a new sense of self and I have not only leveled the playing field from Special Operations soldier to Paralympic athlete . I have eclipsed all previous expectations of who I wanted to be and created a new pinnacle that exceeded all previous achievements and I did it without the use of my legs,” said 2012 U.S. Paralympic Team nominee Eric Hollen. Hollen is not only a top-notch individual, but also a very talented and hard-working shooter. Holllen was awarded USA Shooting’s 2010 and 2011 Paralympic Athlete of the Year distinction, and most notably, he was recently nominated to the 2012 U.S. -

Lones Wigger: Legend Lost 1937-2017 “We Can Say with Great Assurance That He Didn’T Make a Dime Over His 20 Years of Practicing Tens of Thousands of Hours of Shooting

Lones Wigger: Legend Lost 1937-2017 “We can say with great assurance that he didn’t make a dime over his 20 years of practicing tens of thousands of hours of shooting. He didn’t do it for the money. He did it – as the ancient Greeks did – for the glory of sport.” - Dr. John Lucas, Ph.D., an Olympic historian on Lones Wigger’s induction to the Olympic Hall of Fame in 2008. Ret. Army Lt. Col. Lones W. Wigger, a four-time Olympian and the most decorated shooter in the world, passed away on the evening of December 14, 2017 at his home in Colorado Springs, Colorado of complications from pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old. During his induction to the Olympic Hall of Fame in 2008, Wigger’s daughter and 1983 Pan American Games teammate, Deena, said her father “has paid more back to the sport of shooting than he ever got out of it.” Wigger’s illustrious international shooting career spanned 25 years and saw him winning 111 medals and setting 29 world records, along with winning two Olympic gold medals and one silver. Though with all his accomplishments, the generations of young shooters who continue to reap the benefits of his hard work and love for the sport all say the same thing – ‘Wig’ is the best. Wigger’s mark on the sport reaches far beyond his international shooting career. After a distinguished 26-year career in the U.S. Army, Wigger retired in 1987 and went to work for the NRA as the Director of Training for the U.S. -

A.C.C.A. Inc. AGM Auction - Shepparton - 17 Th October 2015

A.C.C.A. Inc. AGM Auction - Shepparton - 17 th October 2015 The following Lots are offered for sale on behalf of various vendors. The vendors have provided most of the item descriptions and estimated prices, and as such the A.C.C.A. cannot accept responsibility for descriptions and conditions of Lots contained herein. All Lots will be on display prior to auction starting times and floor bidders are requested to assure themselves of the accuracy of listings prior to bidding . The ACCA, on behalf of the vendors, offer a 14-day money back guarantee to absentee bidders if Lots are “not as described”. All Lots are offered as collectible items and no other assurances or guarantees are given or implied. In all cases of dispute over terms or descriptions, the Auctioneers decision shall be final. Bids will only be accepted from current financial members who hold an appropriate licence in their State/Country of residence for the type of item being offered. ► Appropriate documentation will be required to register as a Bidder ◄ All Lots won by floor bidders will be delivered to the successful bidder at the time of sale and all accounts will be settled at the completion of the Auction. A Bidding Agent has been appointed for all absentee bidders and absentee bids from other sources will not be accepted. Settlement of absentee bidder’s accounts is required within 14 days of notification of Lots won. Delivery of these Lots will be the sole responsibility of the purchaser and details should be organised with the Bidding Agent prior to the sale. -

Congressional Record-Senate.' 45

1902. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE.' 45 SENATE. praying for the adoption of an amendment to the Constitution to prohibit polygamy; which was referred to the Committee on the THURSDAY, December 4, 1902. Judiciary. Mr. PROCTOR presented a petition of the Reunion Society of Prayet by ~ev. F. J. PRETTYMAN, of the city of Washington. Mr. WlLLIA.M J. DEBOE, a Senator from the State of Kentucky, Vermont Officers, of Vermont, praying for the enactment of legis appeared in his seat ·to-day. lation to commission Bvt. Maj. Gen. William F. Smith a major . The Secretary proceeded to read the Journal of yesterday's pro general in the Regular Army, with the emoluments of a retired ceedings, when, on request of Mr. HALE, and by unanimous con officer of that rank; which was referred to the Committee on Military Affairs. sent, t~e further reading was dispensed with. Mr. McCOMAS presented a petition of the Board <>f Trade of ADJOURNMENT TO MONDAY. Baltimore, Md., praying for the passage of the so-called Ray Mr. HALE. - I move that when the Senate adjourns to-day it bankruptcy bill; which was referred to the Committee on Finance. be to meet on Monday next. He also presented a petition of Lafayette Council, No. 106, The motion was agreed to. Junior Order United American Mechanics, of Baltimore, Md., HEffiS OF SILAS BURKE. praying for the enactment of legislation to restrict immigration; which was ordered to lie on the table. The PRESIDENT pro tempore laid before the Senate a com Mr. FRYE presented a petition of the Reunion Society of Ver munication from the assistant clerk of the Court of Claims, trans mont Officers, of the State of Vermont, praying that Gen. -

RWS-Rossler Titan 6 Rifle by Senior Correspondent John Dunn

RWS-Rossler Titan 6 rifle by senior correspondent John Dunn The Titan 6 Luxus is a handsome rifle with typical Germanic styling. The review rifle was fitted with an 8x Pecar Champion scope for testing. Here, the rifle is set up with the .30-06 barrel. Notice how the larger 4-shot magazine protrudes below the belly of the stock. ne of the nice things about this and special is the fact that it’s a switch barrel the receiver. The one on the left-hand side is gun writing business is that rifle. That has some very practical implica- emblazoned with the Titan 6 name. every now and then something tions in an age where adding a new rifle to All surfaces have a black, anodised finish Olike the RWS-Rossler Titan 6 the gun cabinet is much more complicated that nicely matches the blue/black barrels. rifle comes along and rattles your cage. than it used to be. Even more importantly, the The barrels come without sights and are Graeme Forbes of Forbes Wholesale told barrels can be switched without any need to 570mm long in standard calibres and 610mm me the Titan was on the way in 2005, but change the bolt face. for Magnums. I didn’t actually see the rifle until the 2006 With no fewer than 25 different centrefire Internally, the receiver is round - com- SHOT Expo in Sydney. He and Dieter Schus- calibres to choose from, the Titan range offers pletely lacking any channels or grooves. ter were showing it to all and sundry like a something for everyone.