Micronesia Challenge "We Are One" Business Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Patria É Intereses": Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado

3DWULD«LQWHUHVHV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH2ULJLQVDQG &KDQJLQJ0HDQLQJVRI,OXVWUDGR Caroline Sy Hau Philippine Studies, Volume 59, Number 1, March 2011, pp. 3-54 (Article) Published by Ateneo de Manila University DOI: 10.1353/phs.2011.0005 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/phs/summary/v059/59.1.hau.html Access provided by University of Warwick (5 Oct 2014 14:43 GMT) CAROLINE SY Hau “Patria é intereses” 1 Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado Miguel Syjuco’s acclaimed novel Ilustrado (2010) was written not just for an international readership, but also for a Filipino audience. Through an analysis of the historical origins and changing meanings of “ilustrado” in Philippine literary and nationalist discourse, this article looks at the politics of reading and writing that have shaped international and domestic reception of the novel. While the novel seeks to resignify the hitherto class- bound concept of “ilustrado” to include Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs), historical and contemporary usages of the term present conceptual and practical difficulties and challenges that require a new intellectual paradigm for understanding Philippine society. Keywords: rizal • novel • ofw • ilustrado • nationalism PHILIPPINE STUDIES 59, NO. 1 (2011) 3–54 © Ateneo de Manila University iguel Syjuco’s Ilustrado (2010) is arguably the first contemporary novel by a Filipino to have a global presence and impact (fig. 1). Published in America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and in Great Britain by Picador, the novel has garnered rave reviews across Mthe Atlantic and received press coverage in the Commonwealth nations of Australia and Canada (where Syjuco is currently based). -

Congressional Record—Senate S527

January 26, 1996 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S527 Fayetteville. He was awarded the mas- their efforts. I ask that the letter from vision of Wildlife and Marine Resources ter of arts degree in history and polit- Paul Alan Cox, Ph.D., chairman of the under your leadership has made important ical science from the University of Ar- board of Seacology Foundation to Gov- progress in evaluating and protecting the wildlife of American Samoa. Coastal Zone kansas at Fayetteville and the juris ernor Lutali be printed in the RECORD. The letter follows: Management has flourished under your lead- doctor degree from George Washington ership. But perhaps most important has been University in Washington, DC. THE SEACOLOGY FOUNDATION, your quiet personal example. You quietly led A well-respected executive in the na- Springville, UT. October 24, 1995. an effort to re-introduce the rare Samoa tional electric cooperative community, Gov. A.P. LUTALI, toloa or duck to your home island of Annu’u. Carl also has worked tirelessly in nu- Office of the Governor, American Samoa Gov- The crack of dawn has frequently found you merous civic and community affairs ernment, Pago Pago, American Samoa. on your hands and knees weeding the garden positions in our State and our region. DEAR GOVERNOR LUTALI: On behalf of the plot in front of the territorial offices. Many Board of Directors and the Scientific Advi- Mr. President, wherever Carl have seen you picking up rubbish and doing sory Board of the Seacology Foundation, it your own part as private citizen to beautify Whillock has lived and worked gives me great pleasure to inform you that throughout our State, his support for the exquisite islands of American Samoa. -

Early Colonial History Four of Seven

Early Colonial History Four of Seven Marianas History Conference Early Colonial History Guampedia.com This publication was produced by the Guampedia Foundation ⓒ2012 Guampedia Foundation, Inc. UOG Station Mangilao, Guam 96923 www.guampedia.com Table of Contents Early Colonial History Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas ...................................................................................................1 By Rebecca Hofmann “Casa Real”: A Lost Church On Guam* .................................................13 By Andrea Jalandoni Magellan and San Vitores: Heroes or Madmen? ....................................25 By Donald Shuster, PhD Traditional Chamorro Farming Innovations during the Spanish and Philippine Contact Period on Northern Guam* ....................................31 By Boyd Dixon and Richard Schaefer and Todd McCurdy Islands in the Stream of Empire: Spain’s ‘Reformed’ Imperial Policy and the First Proposals to Colonize the Mariana Islands, 1565-1569 ....41 By Frank Quimby José de Quiroga y Losada: Conquest of the Marianas ...........................63 By Nicholas Goetzfridt, PhD. 19th Century Society in Agaña: Don Francisco Tudela, 1805-1856, Sargento Mayor of the Mariana Islands’ Garrison, 1841-1847, Retired on Guam, 1848-1856 ...............................................................................83 By Omaira Brunal-Perry Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas By Rebecca Hofmann Research fellow in the project: 'Climates of Migration: -

On the Relative Isolation of a Micronesian Archipelago During The

The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (2007) 36.2: 353–364 doi: 10.1111/j.1095-9270.2007.00147.x OnBlackwellR.NAUTICAL CALLAGHAN Publishing ARCHAEOLOGY, and Ltd S. M. FITZPATRICK: XXXthe ON THE RELATIVE ISOLATIONRelative OF A MICRONESIAN ARCHIPELAGO Isolation of a Micronesian Archipelago during the Historic Period: the Palau Case-Study Richard Callaghan Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada Scott M. Fitzpatrick Department of Sociology & Anthropology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA Contact between Europeans and Pacific Islanders beginning in the early 1500s was both accidental and intentional. Many factors played a role in determining when contacts occurred, but some islands remained virtually isolated from European influence for decades or even centuries. We use Palau as a case-study for examining why this archipelago was free from direct European contact until 1783, despite repeated attempts by the Spanish to reach it from both the Philippines and Guam. As computer simulations and historical records indicate, seasonally-unfavourable winds and currents account for the Spanish difficulty. This inadvertently spared Palauans from early Spanish missionaries, disease, and rapid cultural change. © 2007 The Authors Key words: computer simulations, seafaring, Spanish contact, Palau, Caroline Islands, Micronesia. he first contacts between Europeans and world’s largest ocean and most island groups native Pacific Islanders occurred in the consist of small, not-very-visible coral atolls. In T early 1500s. This was, of course, a major addition, relatively few European ships made historical event which ultimately transformed the their way into the Pacific in the 16th and 17th lives of thousands of people through the spread centuries, thereby reducing the chances of contact. -

Vigía: the Network of Lookout Points in Spanish Guam

Vigía: The Network of Lookout Points in Spanish Guam Carlos Madrid Richard Flores Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center There are indications of the existence of a network of lookout points around Guam during the 18th and 19th centuries. This is suggested by passing references and few explicit allusions in Spanish colonial records such as early 19th Century military reports. In an attempt to identify the sites where those lookout points might have been located, this paper surveys some of those references and matches them with existing toponymy. It is hoped that the results will be of some help to archaeologists, historic preservation staff, or anyone interested in the history of Guam and Micronesia. While the need of using historic records is instrumental for the abovementioned purposes of this paper, focus will be given to the Chamorro place name Bijia. Historical evolution of toponymy, an area of study in need of attention, offers clues about the use or significance that a given location had in the past. The word Vigía today means “sentinel” in Spanish - the person who is responsible for surveying an area and warn of possible dangers. But its first dictionary definition is still "high tower elevated on the horizon, to register and give notice of what is discovered". Vigía also means an "eminence or height from which a significant area of land or sea can be seen".1 Holding on to the latter definition, it is noticeable that in the Hispanic world, in large coastal territories that were subjected to frequent attacks from the sea, the place name Vigía is relatively common. -

Invitation for Bids

Invitation for Bids (Please refer to Corrigendum 1 IFB, published on 22 September 2020) Date: 4 May 2020 Grant No. Grant Nos. 0680-FSM and Title: FSM Renewable Energy Development Project ICB-FSMREDP-01 Contract No. Supply and installation of both rooftop and ground mounted Solar PV and Title: Generation including an integrated Battery Storage system; and Supply and installation of both rooftop and ground mounted Solar PV Generation Deadline for Extended to 9 October 2020 at 2:00pm (local time Palikir, Pohnpei, Submission of Federated States of Micronesia) Bids: 1. The Government of the Federated States of Micronesia has received financing from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) toward the cost of the FSM Renewable Energy Development Project (FSMREDP). Part of this financing will be used for payments under the contracts named above. Bidding is open to prequalified Bidders from eligible source countries of ADB. 2. The Government of Federated States of Micronesia - Department of Resources and Development (“the Employer”) invites sealed bids from prequalified eligible Bidders for the construction and completion of: Lot 1 Island of Yap. To supply and install an 800 kW / 800 kWh BESS at the Yap State Public Service Corporation power station, to supply and install 300 kW rooftop solar PV at the sports centre, and at least 1.6 MW of ground mounted solar PV connected to the Yap main grid near to the power station (but not including system integration work to be done by others). Lot 2 Island of Kosrae. To supply and install at least 1.0 MW of ground mounted and rooftop solar PV connected to the Kosrae main grid. -

A Summary of Palau's Typhoon History 1945-2013

A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History 1945-2013 Coral Reef Research Foundation, Palau Dec, 2014 © Coral Reef Research Foundation 2014 Suggested citation: Coral Reef Research Foundation, 2014. A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History. Technical Report, 17pp. www.coralreefpalau.org Additions and suggestions welcome. Please email: [email protected] 2 Summary: Since 1945 Palau has had 68 recorded typhoons, tropical storms or tropical depressions come within 200 nmi of its islands or reefs. At their nearest point to Palau, 20 of these were typhoon strength with winds ≥64kts, or an average of 1 typhoon every 3 years. November and December had the highest number of significant storms; July had none over 40 kts and August had no recorded storms. Data Compilation: Storms within 200 nmi (nautical miles) of Palau were identified from the Digital Typhoon, National Institute of Informatics, Japan web site (http://agora.ex.nii.ac.jp/digital- typhoon/reference/besttrack.html.en). The storm tracks and intensities were then obtained from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) (https://metoc.ndbc.noaa.gov/en/JTWC/). Three storm categories were used following the JTWC: Tropical Depression, winds ≤ 33 kts; Tropical Storm, winds 34-63 kts; Typhoon ≥64kts. All track data was from the JTWC archives. Tracks were plotted on Google Earth and the nearest distance to land or reef, and bearing from Palau, were measured; maximum sustained wind speed in knots (nautical miles/hr) at that point was recorded. Typhoon names were taken from the Digital Typhoon site, but typhoon numbers for the same typhoon were from the JTWC archives. -

Vegetation Mapping of the Mariana Islands: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and Territory of Guam

VEGETATION MAPPING OF THE MARIANA ISLANDS: COMMONWEALTH OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS AND TERRITORY OF GUAM NOVEMBER 2017 FINAL REPORT FRED AMIDON, MARK METEVIER1 , AND STEPHEN E. MILLER PACIFIC ISLAND FISH AND WILDLIFE OFFICE, U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE, HONOLULU, HI 1 CURRENT AGENCY: BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT, MEDFORD, OR Photograph of Alamagan by Curt Kessler, USFWS. Mariana Island Vegetation Mapping Final Report November 2017 CONTENTS List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 List of Tables .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Description of Project Area ........................................................................................................................................... -

Palauan Migrants on Guam

Ethnic Institutions and Identity: Palauan Migrants on Guam RICHARD D . SHEWMAN Departm ent of Anthrop ology , University of Guam, UOG Station Mangi/ao, Guam 96913 Abstract- There are over one thousand Palauan migrants residing on Guam. They have been able to adapt to life on Guam relati vely successfully while continuing to view themselves as Palauans and retaining close ties with Palau . The primary mechani sms in the maintenanc e of their identit y are the Pal a uan institution s. Similar in many resp ects to tho se found in Palau , the migrant institutions have their base in the kinship units , telungalek /kebliil, but va ry from the original as accommodation to life on Guam ha s demanded. These institution s give the migrants a context in which Pal auan langua ge and role relation ships can be experienced and channel s of reciprocity with Palau and among the migrant s ma intained. They also make adju stment to life on Gu am easier by pro viding a source of financi al, social , emotion al, and spiritual support to the migrant. • Palauan migrants residing on Guam present an example of a migrant ethnic group that is in the process of adaptating to a new social environment. My research was conducted among the Palauans of Guam from September 1977 through January 1978. One of the issues this research addressed was the maintenance of a Palauan ethnic identity while living on Guam. This article presents a brief description of the Palauan population on Guam and its social institutions , as they relate to the maintenance of Palauan ethnic identity and assist in a successful adaptation to life in the new environment. -

Renewable Energy Development Project

Project Number: 49450-023 November 2019 Pacific Renewable Energy Investment Facility Federated States of Micronesia: Renewable Energy Development Project This document is being disclosed to the public in accordance with ADB’s Access to Information Policy. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS The currency unit of the Federated States of Micronesia is the United States dollar. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BESS – battery energy storage system COFA – Compact of Free Association DOFA – Department of Finance and Administration DORD – Department of Resources and Development EIRR – economic internal rate of return FMR – Financial Management Regulations FSM – Federated States of Micronesia GDP – gross domestic product GHG – greenhouse gas GWh – gigawatt-hour KUA – Kosrae Utilities Authority kW – kilowatt kWh – kilowatt-hour MW – megawatt O&M – operation and maintenance PAM – project administration manual PIC – project implementation consultant PUC – Pohnpei Utilities Corporation TA – technical assistance YSPSC – Yap State Public Service Corporation NOTE In this report, “$” refers to United States dollars unless otherwise stated. Vice-President Ahmed M. Saeed, Operations 2 Director General Ma. Carmela D. Locsin, Pacific Department (PARD) Director Olly Norojono, Energy Division, PARD Team leader J. Michael Trainor, Energy Specialist, PARD Team members Tahmeen Ahmad, Financial Management Specialist, Procurement, Portfolio, and Financial Management Department (PPFD) Taniela Faletau, Safeguards Specialist, PARD Eric Gagnon, Principal Procurement Specialist, -

El Niño and Its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei And

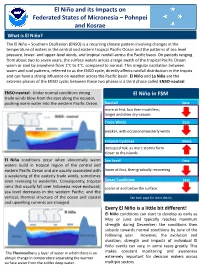

El Niño and its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei and Kosrae What is El Niño? The El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the patterns of sea level pressure, lower- and upper-level winds, and tropical rainfall across the Pacific basin. On periods ranging from about two to seven years, the surface waters across a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm or cool by anywhere from 1°C to 3°C, compared to normal. This irregular oscillation between warm and cool patterns, referred to as the ENSO cycle, directly affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather across the Pacific basin. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle; between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral. ENSO-neutral: Under normal conditions strong El Niño in FSM trade winds blow from the east along the equator, pushing warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Rainfall Less more at first, but then much less; longer and drier dry-season Trade Winds Less weaker, with occasional westerly winds Tropical Cyclones More increased risk, as more storms form closer to the islands El Niño conditions occur when abnormally warm Sea Level Less waters build in tropical region of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and are usually associated with lower at first, then gradually recovering a weakening of the easterly trade winds, sometimes even reversing to westerlies. -

Micronesia 2020 Human Rights Report

MICRONESIA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Federated States of Micronesia is a constitutional republic composed of four states: Chuuk, Kosrae, Pohnpei, and Yap. Individual states enjoy significant autonomy, and their traditional leaders retain considerable influence, especially in Pohnpei and Yap. In March 2019 national elections were held for the 14-seat unicameral Congress; 10 senators were elected in single-seat constituencies to two- year terms, and four (one per state) to four-year terms. Following the election, the Congress selected the new president, David W. Panuelo. Observers considered the election generally free and fair, and the transfer of power was uneventful. The national police are responsible for enforcing national laws, and the Department of Justice oversees them. The four state police forces are responsible for law enforcement in their respective states and are under the jurisdiction of the director of public safety for each state. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over national and state police forces. Members of the security forces were not reported to have committed abuses. There were no reports of significant human rights abuses. The government sometimes took steps to identify, investigate, prosecute, and punish officials, but impunity was a problem, particularly for corruption. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary Deprivation of Life and Other Unlawful or Politically Motivated Killings There were no reports the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. In October 2019 Rachelle Bergeron, a U.S. citizen who was the acting attorney general for Yap State, was murdered in front of her home; observers believed it may have been related to her work as acting attorney general.