The" Puerto Ricanization" of Florida: Historical Background and Current

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Puerto Ricans at the Dawn of the New Millennium

puerto Ricans at the Dawn of New Millennium The Stories I Read to the Children Selected, Edited and Biographical Introduction by Lisa Sánchez González The Stories I Read to the Children documents, for the very first time, Pura Belpré’s contributions to North Puerto Ricans at American, Caribbean, and Latin American literary and library history. Thoroughly researched but clearly written, this study is scholarship that is also accessible to general readers, students, and teachers. Pura Belpré (1899-1982) is one of the most important public intellectuals in the history of the Puerto Rican diaspora. A children’s librarian, author, folklorist, translator, storyteller, and puppeteer who began her career the Dawn of the during the Harlem Renaissance and the formative decades of The New York Public Library, Belpré is also the earliest known Afro-Caribeña contributor to American literature. Soy Gilberto Gerena Valentín: New Millennium memorias de un puertorriqueño en Nueva York Edición de Carlos Rodríguez Fraticelli Gilberto Gerena Valentín es uno de los personajes claves en el desarrollo de la comunidad puertorriqueña Edwin Meléndez and Carlos Vargas-Ramos, Editors en Nueva York. Gerena Valentín participó activamente en la fundación y desarrollo de las principales organizaciones puertorriqueñas de la postguerra, incluyendo el Congreso de Pueblos, el Desfile Puertorriqueño, la Asociación Nacional Puertorriqueña de Derechos Civiles, la Fiesta Folclórica Puertorriqueña y el Proyecto Puertorriqueño de Desarrollo Comunitario. Durante este periodo también fue líder sindical y comunitario, Comisionado de Derechos Humanos y concejal de la Ciudad de Nueva York. En sus memorias, Gilberto Gerena Valentín nos lleva al centro de las continuas luchas sindicales, políticas, sociales y culturales que los puertorriqueños fraguaron en Nueva York durante el periodo de a Gran Migracíón hasta los años setenta. -

Code-Switching and Translated/Untranslated Repetitions in Nuyorican Spanglish

E3S Web of Conferences 273, 12139 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202127312139 INTERAGROMASH 2021 Code-switching and translated/untranslated repetitions in Nuyorican Spanglish Marina Semenova* Don State Technical University, 344000, Rostov-on-Don, Russia Abstract. Nuyorican Spanglish is a variety of Spanglish used primarily by people of Puerto Rican origin living in New York. Like many other varieties of the hybrid Spanglish idiom, it is based on extensive code- switching. The objective of the article is to discuss the main features of code-switching as a strategy in Nuyrican Spanglish applying the methods of linguistic, componential, distribution and statistical analysis. The paper focuses on prosiac and poetic texts created in Nuyrican Spanglish between 1978 and 2020, including the novel Yo-Yo Boing! by Giannina Braschi and 142 selected Boricua poems, which allows us to make certain observations on the philosophy and identity of Nuyorican Spanglish speakers. As a result, two types of code-switching as a strategy are denoted: external and internal code-switching for both written and oral speech forms. Further, it is concluded that repetition, also falling into two categories (translated and untranslated), embodies the core values of Nuyorican Spanglish (freedom of choice and focus on the linguistic personality) and reflects the philosophical basis for code-switching. 1 Introduction Nuyorican Spanglish is a Spanglish dialect used in New York’s East Side primarily by people of Puerto Rican origin, many of who are first- or second-generation New Yorkers. This means that Spanglish they use is rather the most effective way to communicate between English and Spanish cultures which come into an extremely intense contact in this cosmopolitan city. -

Slaves in the Family: Testamentary Freedom and Interracial Deviance

Syracuse University SURFACE College of Law - Faculty Scholarship College of Law Summer 7-26-2012 Slaves in the Family: Testamentary Freedom and Interracial Deviance Kevin Noble Maillard Syracuse University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/lawpub Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Maillard, Kevin Noble, "Slaves in the Family: Testamentary Freedom and Interracial Deviance" (2012). College of Law - Faculty Scholarship. 76. https://surface.syr.edu/lawpub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Law - Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Slaves in the Family: Testamentary Freedom and Interracial Deviance Kevin Noble Maillard* Syracuse University College of Law [email protected] (917) 698-6362 ABSTRACT This Article addresses the deviance of interracial sexuality acknowledged in testamentary documents. The language of wills calls into question the authority of probate and family law by forcing issues of deviance into the public realm. Will dramas, settled in or out of court, publicly unearth insecurities about family. Many objections to the stated intent of the testator generate from social prejudices toward certain kinds of interpersonal relationships: nonmarital, homosexual, and/or interracial. When pitted against an issue of a moral or social transgression, testamentary intent often fails. In order for these attacks on testamentary validity to succeed, they must be situated within an existing juridical framework that supports and adheres to the hegemony of denial that refuses to legitimate the wishes of the testator. -

Introduction

Introduction Frederick Luis Aldama Scholar, playwright, spoken-word performer, award-winning poet, and avant-garde fiction author, since the 1980s Giannina Braschi has been creating up a storm in and around a panoply of Latinx hemispheric spaces. Her creative corpus reaches across different genres, regions, and historical epochs. Her critical works cover a wide range of subjects and authors, including Miguel de Cervantes, Garcilaso de la Vega, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, Antonio Machado, César Vallejo, and García Lorca. Her dramatic poetry titles in Spanish include Asalto al tiempo (1981) and La comedia profana (1985). Her radically ex- perimental genre-bending titles include El imperio de los sueños (1988), the bilingual Yo-Yo Boing! (1998), and the English-penned United States of Banana (2011). With national and international awards and works ap- pearing in Swedish, Slovenian, Russian, and Italian, she is recognized as one of today’s foremost experimental Latinx authors. Her vibrant bilingually shaped creative expressions and innovation spring from her Latinidad, her Puerto Rican-ness that weaves in and through a planetary aesthetic sensibility. We discover as much in her work about US/Puerto Rico sociopolitical histories as we encounter the metaphysical and existential explorations of a Cervantes, Rabelais, Did- erot, Artaud, Joyce, Beckett, Stein, Borges, Cortázar, and Rosario Castel- lanos, for instance. With every flourish of her pen Braschi reminds us that in the distillation and reconstruction of the building blocks of the uni- verse there are no limits to what fiction can do. And, here too, the black scratches that form words and carefully composed blank spaces shape an absent world; her strict selection out of words and syntax is as important as the precise insertion of words and syntax to put us into the shoes of the “complicit reader” (Julio Cortázar’s term) to most productively interface, invest, and fill in the gaps of her storyworlds. -

College of Arts and Sciences

60 Study Abroad All students planning international study are strongly ate courses both here at Fairfield University and your encouraged to plan ahead to maximize program oppor- destination . Be sure to attend the Study Abroad Fair tunities and to ensure optimal match of major, minor, in September and attend a Study Abroad 101 session . previous language studies and intended destination . For Sophomores: attend a Study Abroad 101 meeting Study abroad is intended to build upon and enhance to get information about the application process and majors and minors and for this reason, program the steps required before your departure . Learn about choices will be carefully reviewed to ensure fit between your options and discuss them with your academic academics and destination . advisor, faculty, and family . For fall/spring programs in your Junior year: the deadline in February 1 . For Credits for studying abroad will only be granted for Juniors: you may study abroad during the fall of your academic work successfully completed in approved senior year at Fairfield programs for which grades international programs . All coursework must receive as well as credits are recorded . Applications are due pre-approval (coordinated through the International February 1 of Junior year to go abroad Fall of Senior Programs Office) . Only pre-approved courses, taken at year . To learn more about all our semester, summer, an approved program location, will be transcripted and spring break and intersession programs, consult with a accepted into a student’s curriculum . study abroad advisor or visit the study abroad website Fairfield University administers its own programs in for the current offerings . -

District of Columbia Statehood and Voting Representation

Updated June 29, 2020 District of Columbia Statehood and Voting Representation On June 26, 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives have included full statehood or more limited methods of considered and passed the Washington, D.C. Admission providing DC residents the ability to vote in congressional Act, H.R. 51. This marked the first time in 27 years a elections. Some Members of Congress have opposed these District of Columbia (DC) statehood bill was considered on legislative efforts and recommended maintaining the status the floor of the House of Representatives, and the first time quo. Past legislative proposals have generally aligned with in the history of Congress a DC statehood bill was passed one of the following five options: by either the House or the Senate. 1. a constitutional amendment to give DC residents voting representation in This In Focus discusses the political status of DC, identifies Congress; concerns regarding DC representation, describes selected issues in the statehood process, and outlines some recent 2. retrocession of the District of Columbia DC statehood or voting representation bills. It does not to Maryland; provide legal or constitutional analysis on DC statehood or 3. semi-retrocession (i.e., allowing qualified voting representation. It does not address territorial DC residents to vote in Maryland in statehood issues. For information and analysis on these and federal elections for the Maryland other issues, please refer to the CRS products listed in the congressional delegation to the House and final section. Senate); 4. statehood for the District of Columbia; District of Columbia and When ratified in 1788, the U.S. -

Style Sheet for Aztlán: a Journal of Chicano Studies

Style Sheet for Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies Articles submitted to Aztlán are accepted with the understanding that the author will agree to all style changes made by the copyeditor unless the changes drastically alter the author’s meaning. This style sheet is intended for use with articles written in English. Much of it also applies to those written in Spanish, but authors planning to submit Spanish-language texts should check with the editors for special instructions. 1. Reference Books Aztlán bases its style on the Chicago Manual of Style, 15th edition, with some modifications. Spelling follows Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th edition. This sheet provides a guide to a number of style questions that come up frequently in Aztlán. 2. Titles and Subheads 2a. Article titles No endnotes are allowed on titles. Acknowledgments, information about the title or epigraph, or other general information about an article should go in an unnumbered note at the beginning of the endnotes (see section 12). 2b. Subheads Topical subheads should be used to break up the text at logical points. In general, Aztlán does not use more than two levels of subheads. Most articles have only one level. Authors should make the hierarchy of subheads clear by using large, bold, and/or italic type to differentiate levels of subheads. For example, level-1 and level-2 subheads might look like this: Ethnocentrism and Imperialism in the Imperial Valley Social and Spatial Marginalization of Latinos Do not set subheads in all caps. Do not number subheads. No endnotes are allowed on subheads. -

Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S

Draft Environmental Assessment for the Repairs and Replacement of the Boat Ramp and Pier at the US Border Patrol Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S. Border Patrol & Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico U.S. Customs and Border Protection February 2019 Draft Environmental Assessment for the Repairs and Replacement of the Boat Ramp and Pier at the US Border Patrol Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S. Border Patrol & Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S. Border Patrol & Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Lead Agency: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Proposed Action: The demolition and removal of the temporary structure, removal of the original pier, construction of a new pier, and replacement of the boat ramp at 41 Bonaire Street in the municipality of Ponce, Puerto Rico. The replacement boat ramp would be constructed in the same location as the existing boat ramp, and the pier would be constructed south of the Ponce Marine Unit facility. For Further Information: Joseph Zidron Real Estate and Environmental Branch Chief Border Patrol & Air and Marine Program Management Office 24000 Avila Road, Suite 5020 Laguna Niguel, CA 92677 [email protected] Date: February 2019 Abstract: CBP proposes to remove the original concrete pier, demolish and remove the temporary structure, construct a new pier, replace the existing boat ramp, and continue operation and maintenance at its Ponce Marine Unit facility at 41 Bonaire Street, Ponce, Puerto Rico. -

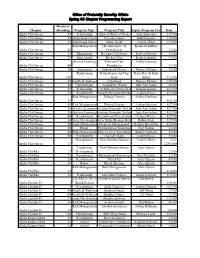

S08 Chapter Programming Report

Office of Fraternity Sorority Affairs Spring 08 Chapter Programming Report Members Chapter Attending Program Type Program Title Chapter Program Cord. Date Alpha Chi Omega 45 Scholarship How to Write a Check Judy Sukovich 1/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 25 Sisterhood Event Pancake Dinner Juaki Kapadia 1/28/08 Alpha Chi Omega 35 Sisterhood Mixer Game Night Jennifer Ross 2/15/08 Risk Management The Importance of Kathleen Mullen Alpha Chi Omega 45 Checking In 3/2/08 Alpha Chi Omega 33 Educational By Law Cliff Notes Kaitlyn Herthel 3/3/08 Alpha Chi Omega 33 Educational By-Law Day Kaitlyn Herthel 3/3/08 Service Learning Embrace Kids Ashley Garrison Alpha Chi Omega 40 Foundation 3/9/08 Alpha Chi Omega 20 Sisterhood Sisterhood Dinner Monica Milano 3/9/08 Fundraising Philanthropy and Flap Katie Karr & Judy Alpha Chi Omega 188 Jacks Adam 3/12/08 Alpha Chi Omega 38 Health & Wellness Sisterhood Monica Milano 3/29/08 Alpha Chi Omega 84 Philanthropy Around the World Judy Ann Adam 4/2/08 Alpha Chi Omega 55 ScholarshipHow to Write the Perfect E-MailJennifer Kantor 4/13/08 Alpha Chi Omega 25 Recruitment Sorority Recruitment Fair Lauren Ricca 4/15/08 Risk Management Taking Chances Ashley Garrison Alpha Chi Omega 27 4/21/08 Alpha Chi Omega 43 Risk Management Hazing Policies Ashley Garrison 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 36 Service LearningPreventing Domestic Violence Judy Ann Adam 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 36 Service LearningPreventing Domestic Violence Judy Ann Adam 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 40 Recruitment Recruitment Presentation Lauren Ricca 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 30Career -

Ruling America's Colonies: the Insular Cases Juan R

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Ruling America's Colonies: The Insular Cases Juan R. Torruella* INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 58 I. THE HISTORICAL BACKDROP TO THE INSULAR CASES..................................-59 11. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ......................................... 65 III. LIFE AFTER THE INSULAR CASES.......................... .................. 74 A. Colonialism 1o ......................................................... 74 B. The Grinding Stone Keeps Grinding........... ....... ......................... 74 C. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and President Taft ................. 75 D. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and ChiefJustice Taft ............ 77 E. Local Self-Government v. Colonial Status...........................79 IV. WHY THE UNITED STATES-PUERTO Rico RELATIONSHIP IS COLONIAL...... 81 A. The PoliticalManifestations of Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......82 B. The Economic Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's ColonialRelationship.....82 C. The Cultural Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......89 V. THE COLONIAL STATUS OF PUERTO Rico Is UNAUTHORIZED BY THE CONSTITUTION AND CONTRAVENES THE LAW OF THE LAND AS MANIFESTED IN BINDING TREATIES ENTERED INTO BY THE UNITED STATES ............................................................. 92 CONCLUSION .................................................................... 94 * Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. The substance of this Article was presented in -

Testimony Medicaid and CHIP in the U.S. Territories

Statement of Anne L. Schwartz, PhD Executive Director Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission Before the Health Subcommittee Committee on Energy and Commerce U.S. House of Representatives March 17, 2021 i Summary Medicaid and CHIP play a vital role in providing access to health services for low-income individuals in the five U.S. territories: American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The territories face similar issues to those in the states: populations with significant health care needs, an insufficient number of providers, and constraints on local resources. With some exceptions, they operate under similar federal rules and are subject to oversight by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. However, the financing structure for Medicaid in the territories differs from state programs in two key respects. First, territorial Medicaid programs are constrained by an annual ceiling on federal financial participation, referred to as the Section 1108 cap or allotment (§1108(g) of the Social Security Act). Territories receive a set amount of federal funding each year regardless of changes in enrollment and use of services. In comparison, states receive federal matching funds for each state dollar spent with no cap. Second, the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) is statutorily set at 55 percent rather than being based on per capita income. If it were set using the state formula, the matching rate for all five territories would be significantly higher, and for most, would likely be the maximum of 83 percent. These two policies have resulted in chronic underfunding of Medicaid in the territories, requiring Congress to step in at multiple points to provide additional resources. -

Excavations at Maruca, a Preceramic Site in Southern Puerto Rico

EXCAVATIONS AT MARUCA, A PRECERAMIC SITE IN SOUTHERN PUERTO RICO Miguel Rodríguez ABSTRACT A recent set of radiocarbon dated shows that the Maruca site, a preceramic site located in the southern coastal plains of Puerto Rico, was inhabited between 5,000 and 3,000 B.P. bearing the earliest dates for human habitation in Puerto Rico. Also the discovery in the site of possible postmolds, lithic and shell workshop areas and at least eleven human burials strongly indicate the possibility of a permanent habitation site. RESUME Recientes fechados indican una antigüedad entre 5,000 a 3000 años antes de del presente para Maruca, una comunidad Arcaica en la costa sur de Puerto Rico. Estos son al momento los fechados más antiguos para la vida humana en Puerto Rico. El descubrimiento de socos, de posible talleres líticos, de áreas procesamiento de moluscos y por lo menos once (11) enterramientos humanos sugieren la posibilidad de que Maruca sea un lugar habitation con cierta permanence. KEY WORDS: Human Remains, Marjuca Site, Preceramic Workshop. INTRODUCTION During the 1980s archaeological research in Puerto Rico focused on long term multidisciplinary projects in early ceramic sites such as Sorcé/La Hueca, Maisabel and Punta Candelera. This research significantly expanded our knowledge of the life ways and adaptive strategies of Cedrosan and Huecan Saladoid cultures. Although the interest in these early ceramic cultures has not declined, it seems that during the 1990s, archaeological research began to develop other areas of interest. With the discovery of new preceramic sites of the Archaic age found during construction projects, the attention of specialists has again been focused on the first in habitants of Puerto Rico.