Southern Africa Labour ,And Development Research Unit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natemis Provincecd Province Institution Name Institution Status

NatEmis ProvinceCD Province Institution Name Institution Status Sector Institution Type Institution Phase Specialization OwnerLand OwnerBuildings GIS_Long GIS_Lat GISSource A G MALEBE MIDDLE ORDINARY INTERMEDIATE COMPREHENSI 600100003 6 NW SCHOOL OPEN PUBLIC SCHOOL SCHOOL VE PUBLIC PUBLIC 25.74965 -26.125 NEIMS 2007 ORDINARY INTERMEDIATE COMPREHENSI 600100001 6 NW A M SETSHEDI OPEN PUBLIC SCHOOL SCHOOL VE PUBLIC PUBLIC 27.99162 -25.04915 NEIMS 2007 ORDINARY INTERMEDIATE COMPREHENSI 600100004 6 NW AALWYN PRIMARY OPEN PUBLIC SCHOOL SCHOOL VE INDEPENDENT INDEPENDENT 27.792333 -25.843 NEIMS 2007 AARON LETSAPA ORDINARY PRIMARY COMPREHENSI 600100006 6 NW PRIMARY OPEN PUBLIC SCHOOL SCHOOL VE PUBLIC PUBLIC 25.30976 -26.28336 NEIMS 2007 ABANA PRIMARY ORDINARY PRIMARY COMPREHENSI 600104024 6 NW SCHOOL OPEN PUBLIC SCHOOL SCHOOL VE PUBLIC PUBLIC 27.32625 -25.6205 NEIMS 2007 ORDINARY PRIMARY COMPREHENSI 600100009 6 NW ABONTLE OPEN PUBLIC SCHOOL SCHOOL VE PUBLIC PUBLIC 26.87401 -26.85016 NEIMS 2007 ORDINARY INTERMEDIATE COMPREHENSI TO BE 600100010 6 NW ACADEMY FOR CHRIST OPEN INDEPENDENT SCHOOL SCHOOL VE PUBLIC PUBLIC 27.773 -25.63467 UPDATED AGAPE ORDINARY COMBINED COMPREHENSI TO BE 600100012 6 NW CHRISTENSKOOL OPEN INDEPENDENT SCHOOL SCHOOL VE PUBLIC PUBLIC 27.08667 -26.723 UPDATED ORDINARY PRIMARY COMPREHENSI 600100013 6 NW AGELELANG THUTO OPEN PUBLIC SCHOOL SCHOOL VE PUBLIC PUBLIC 23.46496 -26.16578 NEIMS 2007 AGISANANG PUBLIC ORDINARY PRIMARY COMPREHENSI 600100014 6 NW SCHOOL OPEN PUBLIC SCHOOL SCHOOL VE PUBLIC PUBLIC 25.82308 -26.55926 NEIMS 2007 -

Insights from Selected Case Studies

Water Research Commission 40 Year Celebration Conference 31 August – 1 September 2011; Emperor‟s Palace, Kempton Park, Johannesburg (South Africa) BLUE vs. TRUE GOLD Impacts of deep level gold mining on water resources in South Africa – insights from selected case studies Frank Winde NWU Potchefstroom Campus Mine Water Research Group Contents (1) Introduction (2) Au mining impacts on water resources: 3 x case studies (A) Dewatering of karst aquifers (B) Uranium pollution (C) Flooding of mine voids (AMD decant) (3) The future? Largest urban agglomeration in Africa: - triggered by Au rush 125 years ago, today: - 25% population SA - 50% of energy consumption in Africa - 70% GDP SA Ferreira Camp (1886) ~400 x diggers - 70 km from nearest major river: strongly negative water balance imports from Lesotho Johannesburg (2011) ~4 million residents 50 Total surface runoff ) 45 40 km³/a 35 Economically 30 exploitable run off 25 demand ( demand 20 15 total water water 10 5 0 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 125 years of Au production: >6 bn t of tailings covering ~400 km² Total since 1886: 42,000 t 1970: Peak of SA gold production (989 t) = 68% of world production 17m all gold ever poured: 127 000 t Au 17m 33%: SA worldwide more steel is poured in 1 hour …1700 1400 Au-prize [$/oz] 1300 ‚Sunset industry‘? SA: 35.000t Au still available 1200 15 kt accessible with current technology 20 kt ultra deep mining needed 1100 1000 900 800 700 600 price [US$/ ounce] [US$/ price - 500 Au 400 WDL 300 200 m 4300 > 100 0 2011 1900 1870 1880 1890 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 2010 1850 1860 1960 1990 2000 1970 1980 1800 1810 1820 1830 1840 1. -

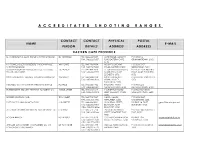

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

MATLOSANA City on the Move?

[Type text] MATLOSANA City on the Move? SACN Programme: Secondary Cities Document Type: SACN Report Paper Document Status: Final Date: 10 April 2014 Joburg Metro Building, 16th floor, 158 Loveday Street, Braamfontein 2017 Tel: +27 (0)11-407-6471 | Fax: +27 (0)11-403-5230 | email: [email protected] | www.sacities.net 1 [Type text] CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. Historical perspective 3 3. Current status and planning 6 3.1 Demographic and population change 6 3.2 Social issues 12 3.3 Economic analysis 16 3.3.1 Economic profile 17 3.3.2 Business overview 26 3.3.3 Business / local government relations 31 3.4 Municipal governance and management 33 3.5 Overview of Integrated Development Planning (IDP) 34 3.6 Overview of Local Economic Development (LED) 39 3.7 Municipal finance 41 3.7.1 Auditor General’s Report 42 3.7.2 Income 43 3.7.3 Expenditure 46 3.8 Spatial planning 46 3.9 Municipal services 52 3.9.1 Housing 52 3.9.2 Drinking and Waste Water 54 3.9.3 Electricity 58 4. Natural resources and the environment 60 5. Innovation, knowledge economy and human capital formation 60 5.1 Profile of existing research 63 6. Synthesis 65 ANNEXURES 67 ANNEXURE 1: Revenue sources for the City of Matlosana Local Municipality R’000 (2006/7–2012/13) 67 i [Type text] LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Position of the City of Matlosana Local Municipality in relation to the rest of the Dr Kenneth Kaunda District Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 1 Figure 2: Population and household growth for the City of Matlosana (1996–2011) .................................. -

App D14 Socio-Economic Impact Assessment

PROPOSED KAREERAND TAILINGS STORAGE FACILITY (TSF) EXPANSION PROJECT, NEAR STILFONTEIN, NORTH WEST PROVINCE GCS REFERENCE NO: 17-0026 SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT: DRAFT Submitted to: GCS (Pty) Ltd. Submitted by: AND October 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Project Background The operations of Mine Waste Solutions (MWS), also known as Chemwes (Pty) Ltd (Chemwes), entail the collection and reprocessing of mine tailings that were previously deposited on tailings storage facilities (TSFs) in order to extract gold and uranium. MWS conducts its operations over a large area of land to the east of Klerksdorp, within the area of jurisdiction of the City of Matlosana and JB Marks Local Municipalities, which fall within the Dr Kenneth Kaunda District Municipality in the North‐West Province. The main operations of MWS include the existing Kareerand Tailings Facility (TSF) located to the south of the N12. The closest town is Khuma, located about 2km northwest of the facility, and other nearby towns include Stilfontein (10 km from facility) and Klerksdorp (19 km from facility). The Kareerand TSF was designed with an operating life of 14 years, taking the facility to 2025, and total design capacity of 352 million tonnes. Subsequent to commissioning of the TSF, MWS was acquired by AngloGold Ashanti (AGA) and the tailings production target has increased by an additional 485 million tonnes, which will require operations to continue until 2042. The additional tailings therefore require extension of the design life of the TSF. The expansion of the existing TSF will enable the reclamation of additional tailings dams and deposition of the tailings in an expanded facility complete with a Class C barrier system and appropriate seepage mitigation measures. -

Sustainable Development Projects SOUTH AFRICA 2012-2013 REGION SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS 2012-2013

The communities and societies in which we operate will be better off for AngloGold Ashanti having been there. Sustainable Development Projects SOUTH AFRICA 2012-2013 REGION SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS 2012-2013 SOUTH AFRICA REGION Exciting Mining Skills Level 2 Learnership opportunities CONTACT DETAILS in AngloGold Ashanti await... Sustainability Simeon Mighty Moloko Malebogo Mahape-Marimo Monica Madondo Application criteria Senior Vice President: Sustainability Vice President: Sustainability Vice President: Sustainability AngloGold Ashanti offers [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 018 290 3023 018 290 3029 018 290 3059 Ÿ Applications are only open to South African citizens below the Mining Skills Learnership Stakeholder Engagement: Sediko Rakolote Ben Matela Xola Bashman age of 30 who hail from our host Stakeholder Engagement Manager Stakeholder Engagement Manager Stakeholder Engagement Manager communities of Merafong Matlosana area Merafong area Labour sending area (Carletonville area), Matlosana opportunities in 2014 to [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (Klerksdorp area) and Moqhaka 018 478 2020 018 700 2914 018 700 2913 (Viljoenskroon area). individuals who meet the Local Economic Development: Maxwell Bolani Mthuthuzeli Pitoyi Mark Till Manager: Local Economic Development Senior CSD Officer Senior CSD Officer Ÿ Candidates must be in [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] possession of the necessary criteria. 018 700 2978 018 700 2913 018 478 6268 documentation such as a valid SA identity document, Enterprise Development: Jacques Wessels Kobus van Heerden Tebogo Hlapi matriculation certificate with Manager: Business Development Enterprise Development Manager Senior Enterprise Development Officer maths or science or latest Grade Written applications, along with a CV may be [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 12 results and proof of residence. -

Provincial Gazette Free State Province

Provincial Provinsiale Gazette Koerant Free State Province Provinsie Vrystaat Published byAuthority Uitgegee op Gesag NO. 73 FRIDAY, 01 FEBRUARY 2013 NO. 73 VRYDAG, 01 FEBRUARIE 2013 PROVINCIAL NOTICE PROVINSIALE KENNISGEWING 117 Development facilitation Act, 1995 (Act No. 67 of 1995): 117 Wet opOntwikkelingsfasilitering, 1995 (Wet No. 67 van Administrative District Parys: Amendment of the Vaal 1995): Administratiewe Distrik Parys: Wysiging van River Complex Regional Structure Plan, 1996: dieVaalrivierkompleks Streekstruktuur Plan, 1996: Remainder of the farm Boschbank 12, remainder of Restant van die plaas Boschbank 12, Restant van Portion 2 of the farm Wonderfontein 350, Portions 2, 5, 8 Gedeelte 2 van dieplaas Wonderfontein 350, Gedeeltes and 10 of the farm Rietfontein 251 2 2,5,8 en 10 van dieplaas Rietfontein 251 2 MISCELLANEOUS Applications For Public Road Carrier Permits: Advert 123 2 Advert 124 49 NOTICES KENNISGEWINGS The Conversion of Certain Rights into Leasehold 83 Wet opdie Omskepping van Sekere Regte totHuurpag 86 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE 1PROVINSIALE KOERANT, 01 FEBRUARY 20131 01 FEBRUARIE 2013 2 PROVINCIAL NOTICE PROVINSIALE KENNISGEWING [NO. 117 OF 2012] [NO. 117 VAN 2012] DEVELOPMENT FACILITATION ACT, 1995 (ACT NO. 67 OF 1995): WET OP ONTWIKKELlNGSFASILITERING, 1995 (WET NO. 67 VAN ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT PARYS: AMENDMENT OF THE VAAL 1995): ADMINISTRATIEWE DISTRIK PARYS: WYSIGING VAN DIE RIVER COMPLEX REGIONAL STRUCTURE PLAN, 1996: VAALRIVIERKOMPLEKS STREEK-STRUKTUUR PLAN, 1996: REMAINDER OF THE FARM BOSCHBANK 12, REMAINDER OF RESTANT VAN DIE PLAAS BOSCHBANK 12, RESTANT VAN PORTION 2 OF THE FARM WONDERFONTEIN 350, PORTIONS 2, GEDEELTE 2 VAN DIE PLAAS WONDERFONTEIN 350, 5,8 AND 10 OF THE FARM RIETFONTEIN 251 GEDEELTES 2,5,8 EN 10 VAN DIE PLAAS RIETFONTEIN 251 Under the powers vested in me by section 29(3) of the Development Kragtens diebevoegdheid myverleen by artikel 29(3) van die Wet op Facilitation Act, 1995 (Act No. -

Facies Mapping of the Vaal Reef Placer

\ FACIES MAPPING OF THE VAAL REEF PLACER AS AN AID TO REMNANT PILLAR EXTRACTION AND STOPE WIDTH OPTIMISATION BY: A.G.O'DONOVAN This assignment is submitted as p artial ful f i l lment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ( Expl o ration Geology) at Rhodes University, Grahamstown. January, 1992. ABSTRACT The Vaal Reef placer is situated on the unconformable junction of the Strathmore and Stilfontein formations of the Johannesburg Subgroup. Within the South Division of the Vaal Reefs Exploration and Mining company lease, the Vaal Reef Placer is shown to be composed of several different units. Each unit exhibits its own specific characteristics and trend direction which can be used to establish distinct "Reef packages". These packages can be mapped in such a way as to provided a preliminary lithofacies map for the Vaal Reef Placer. The delineation of such geologically homogenous zones, and the development of a suitable depositional model, can be utilised in several ways. The characteristics of a particular zone are shown to influence the control of stoping width, evaluation of remnant pillars and the geostatistical methodology of evaluating current and future ore reserve blocks. TITLE PAGE ABSTRACT CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES LIST OF TABLES LIST OF PLATES CHAPTER ONE PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION AIMS OF THE PROJECT..... ................. 1. THE WITWATERSRAND BASIN. .. ................ 2. THE KLERKSDORP GOLDFIELD... ... ............ 2. VAAL REEFS MINE. 5. THE VAAL REEF PLACER....... .. ............. 5. CHAPTER TWO 2. THE GEOLOGY OF THE VAAL REEF STRUCTURE LOCAL STRUCTURAL SETTING........ .... 9. FAULTING. 12. INTRUSIVES ..... .. ............ ,. 13. TECTONIC SETTING ................... " 14. SEDIMENTOLOGY LITHOLOGIES MB5 - FOOTWALL .................. 15. -

Urban Rural (PDF Format)

Published by Statistics South Africa, Private Bag X44, Pretoria 0001 © Statistics South Africa, 2003 Users may apply or process this data, provided Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) is acknowledged as the original source of the data; that it is specified that the application and/or analysis is the result of the user's independent processing of the data; and that neither the basic data nor any reprocessed version or application thereof may be sold or offered for sale in any form whatsoever without prior permission from Stats SA. Stats SA Library Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) Data Census 2001: Investigation into appropriate definitions of urban and rural areas for South Africa: Discussion document/ Statistics South Africa. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2003 195p. [Report No. 03-02-20 (2001)] ISBN 0-621-34336-6 1. Population research – South Africa 2. Population density – South Africa 3. Rural–Urban Migration – Research 4. Geography – Terminology (LCSH 16) This report is available on the Stats SA website: www.statssa.gov.za and by request on CD-Rom. Copies can be ordered from: Printing and Distribution, Statistics South Africa Tel: (012) 310 8251 Fax: (012) 322 3374 E-mail: [email protected] As this is an electronic document, edits and updates can be implemented as they become available. This version was finalised on 15 July 2003. Nothing substantive was altered from the version of 8 July 2003. Census 2001: Investigation into appropriate definitions of urban and rural areas for South Africa: Discussion document CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objectives 1 1.2 Assumptions 1 1.3 Data sources 1 1.4 Geographic structure 1 1.5 The concepts of urban and rural 2 2. -

Sequence Stratigraphy of the Vaal Reef Facies Associations in the Witwatersrand Foredeep, South Africa

Sedimentary Geology 141±142 02001) 113±130 www.elsevier.nl/locate/sedgeo Sequence stratigraphy of the Vaal Reef facies associations in the Witwatersrand foredeep, South Africa Octavian Catuneanua,*, Mark N. Biddulphb aDepartment of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, 1-26 Earth Sciences Building, Edmonton, Alta., Canada T6G 2E3 bGeology Department, Anglogold, Private Bag 5010, Vaal Reefs 2621, South Africa Accepted 19 January 2001 Abstract Facies analysis and sequence stratigraphic methods resolve the correlation and relative chronology of Vaal Reef facies associations at the Great Noligwa and Kopanang mines in the Klerksdorp Gold®eld, Witwatersrand Basin. Four depositional sequences, separated by major erosional surfaces, build the Vaal Reef package. Lowstand, transgressive and highstand systems tracts 0HST) are identi®ed based on stratal stacking patterns and sedimentological features. The core of the Vaal Reef deposit is represented by a Transgressive Systems Tract 0TST), which is built by shoreface 0proximal) facies at Great Noligwa and inner shelf 0distal) facies at Kopanang. The proximal TST includes the G.V. Bosch reef and the overlying MB4 quartzites. These facies are correlative to the Stilfontein conglomerates and quartzites, respectively, at Kopanang. The overlying Upper Vaal Reef is part of a Lowstand Systems Tract 0LST). It is only preserved at Kopanang, with a thickness that equals the difference in thickness between the proximal and distal transgressive facies. This suggests that the Upper Vaal is an erosional remnant that accumulated on a gently dipping topographic pro®le. Traditionally, the MB4 quartzite has been considered the hanging wall relative to the Vaal Reef. We infer that these quartzites are merely associated with the G.V. -

Race Relations Survey: 1986, Part 1

Race relations survey: 1986, Part 1 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.BOO19870000.042.000 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Race relations survey: 1986, Part 1 Author/Creator Cooper, Carole; Shindler, Jennifer; McCaul, Colleen; Brouard, Pierre; Mareka, Cosmas Publisher South African Institute of Race Relations, Johannesburg Date 1987 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, South Africa, South Africa, South Africa, South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1986 Source EG Malherbe Library, ISBN 0969823167, EG Malherbe Library, ISSN 02587246 Description A survey of race relations in South Africa in 1986 (Part 1) and includes chapters on: Population and race classification; Business; The economy; Government and Constitution; Political organisations; Transport; Social segregation; Labour relations; Sport; Religious organisations; Urbanisation; Housing; 1986 Legislation. -

City of Matlosana

Working for integration North West West Rand Ditsobotla Ventersdorp District Dr Kenneth Municipality Kaunda District Ngaka Modiri Municipality Molema District Municipality Tswaing Tlokwe City Council City of Matlosana N12 Moqhaka Mamusa Fezile Maquassi Dabi District Hills Municipality Lejweleputswa District Dr Ruth Segomotsi Municipality Mompati District Ngwathe Municipality Nala Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA City of Matlosana – North West Housing Market Overview Human Settlements Mining Town Intervention 2008 – 2013 The Housing Development Agency (HDA) Block A, Riviera Office Park, 6 – 10 Riviera Road, Killarney, Johannesburg PO Box 3209, Houghton, South Africa 2041 Tel: +27 11 544 1000 Fax: +27 11 544 1006/7 Acknowledgements The Centre for Affordable Housing Finance (CAHF) in Africa, www.housingfinanceafrica.org Coordinated by Karishma Busgeeth & Johan Minnie for the HDA Disclaimer Reasonable care has been taken in the preparation of this report. The information contained herein has been derived from sources believed to be accurate and reliable. The Housing Development Agency does not assume responsibility for any error, omission or opinion contained herein, including but not limited to any decisions made based on the content of this report. © The Housing Development Agency 2015 Contents 1. Frequently Used Acronyms 1 2. Introduction 2 3. Context 5 4. Context: Mining Sector Overview 6 5. Context: Housing 7 6. Context: Market Reports 8 7. Key Findings: Housing Market Overview 9 8. Housing Performance Profile 10 9. Market Size 16 10. Market Activity