Route Choice in Hilly Terrain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waiver and Release, Ver: 9-28-07, Page 1 of 2 WAIVER and RELEASE Auburn Ski Club Associates, Inc. Auburn Ski Club, Inc. Traini

Family Form WAIVER AND RELEASE Auburn Ski Club Associates, Inc. Auburn Ski Club, Inc. Training Center I/We, the undersigned, and/or parent or legal guardian of a minor, desiring to participate in the Alpine and Nordic programs of the Auburn Ski Club Associates, Inc. (“Associates”) hereby acknowledge that the use by myself (each undersigned adult participant) or my/our minor child(ren) of the facilities, equipment or programs of Associates at the Auburn Ski Club Training Center, Boreal Mountain Resort, Alpine Meadows Ski Area, Northstar at Tahoe and other ski areas is permissive only and is subject to the terms of this Release. The facility and other properties utilized by the Associates are owned by a separate corporation, namely Auburn Ski Club, Inc. (“ASC”), and the waivers and releases given pursuant to this Agreement extend to, and are for the benefit of, the Associates, ASC and the other Released Parties that are identified below. This Agreement contains the entire agreement and understanding between the Released Parties and the undersigned concerning the subject matter of this Agreement and supersedes all prior agreements, terms, understandings, conditions, representations and warranties, whether written or oral. I/We acknowledge that the sport of skiing, both Nordic and Alpine, biathlon, snowboarding, orienteering, ski jumping, ski racing, terrain park activities and other related events and activities hosted by Associates, ASC, and/or the Training Center (including, without limitation, weight training, off-snow physical fitness conditioning, fitness testing and the discharge of firearms in connection with biathlon programs) are action sports and related activities which carry a significant risk of personal injury and even death. -

OUTDOOR EDUCATION (OUT) Credits: 4 Voluntary Pursuits in the Outdoors Have Defined American Culture Since # Course Numbers with the # Symbol Included (E.G

University of New Hampshire 1 OUT 515 - History of Outdoor Pursuits in North America OUTDOOR EDUCATION (OUT) Credits: 4 Voluntary pursuits in the outdoors have defined American culture since # Course numbers with the # symbol included (e.g. #400) have not the early 17th century. Over the past 400 years, activities in outdoor been taught in the last 3 years. recreation an education have reflected Americans' spiritual aspirations, imperial ambitions, social concerns, and demographic changes. This OUT 407B - Introduction to Outdoor Education & Leadership - Three course will give students the opportunity to learn how Americans' Season Experiences experiences in the outdoors have influenced and been influenced by Credits: 2 major historical developments of the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th, and early An exploration of three-season adventure programs and career 21st centuries. This course is cross-listed with RMP 515. opportunities in the outdoor field. Students will be introduced to a variety Attributes: Historical Perspectives(Disc) of on-campus outdoor pursuits programming in spring, summer, and fall, Equivalent(s): KIN 515, RMP 515 including hiking, orienteering, climbing, and watersports. An emphasis on Grade Mode: Letter Grade experiential teaching and learning will help students understand essential OUT 539 - Artificial Climbing Wall Management elements in program planning, administration and risk management. You Credits: 2 will examine current trends in public participation in three-season outdoor The primary purpose of this course is an introduction -

Physiological Demands of Mountain Running Races

Rodríguez-Marroyo1, J.A. et al.: PHYSIOLOGICAL DEMANDS OF MOUNTAIN... Kinesiology 50(2018) Suppl.1:60-66 PHYSIOLOGICAL DEMANDS OF MOUNTAIN RUNNING RACES Jose A. Rodríguez-Marroyo1, Javier González-Lázaro2,3, Higinio F. Arribas-Cubero3,4, and José G. Villa1 1Department of Physical Education and Sports, Institute of Biomedicine (IBIOMED), University of León, León, Spain 2European University Miguel de Cervantes, Valladolid, Spain 3Castilla y León Mountain Sports, Climbing and Hiking Federation, Valladolid, Spain 4Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain Original scientific paper UDC: 796.61.093.55:612.766.1 Abstract: The aim of this study was to analyze the exercise intensity and competition load (PL) based on heart rate (HR) during different mountain running races. Seven mountain runners participated in this study. They competed in vertical (VR), 10-25 km, 25-45 km and >45 km races. The HR response was measured during the races to calculate the exercise intensity and PL according to the HR at which both the ventilatory (VT) and respiratory compensation threshold (RCT) occurred. The exercise intensity below VT and between VT and RCT increased with mountain running race distance. Likewise, the percentage of racing time spent above RCT decreased when race duration increased. However, the time spent above RCT was similar between races (~50 min). The PL was significantly higher (p<.05) during the longest races (145.0±18.4, 288.8±72.5, 467.3±109.9 and 820.8±147.0 AU in VR, 10-25 km, 25-45 km and >45 km, respectively). The ratio of PL to accumulative altitude gain was similar in all races (~0.16 AU·m-1). -

Mark Salas Oriented Orienteering with Lots of Fun Surprises

The Wild Times August 2018 ROC helpline: (585) 310-4ROC (4762) Web site: roc.us.orienteering.org Find us on Facebook and on Meetup.com The official newsletter of the Rochester (NY) Orienteering Club ROC President's Corner... by Doug Hall "A volunteering safety bearing" Many of us have had the experience while orienteering of becoming "lost". I have had this experience myself on more than one occasion. It can feel scary not knowing exactly where you are, especially when you don't see or hear other runners . However, there is almost always a sure-fire way to get back to civilization. The "safety bearing" can help you find a road or path to get back to the lodge. It has occurred to me that I have never been truly lost; I always had that safety bearing. I also was never truly alone, because there were people who knew where I had gone and who were awaiting my return. They even knew approximately how long I had been out in the woods. Those people weren't even that far away, really. Coming to this realization turned a scary experience completely on its head. It felt pretty good! Our club is made up of really great people. Volunteers organize and run all of our events, which is one of the reasons why orienteering is such a great bargain in the realm of sports and recreation. There are people who volunteer to create or update the highly detailed maps we all use. Other people volunteer to design multiple courses for an event, so everyone who shows up has an appropriate choice available to them. -

Preparing the Event

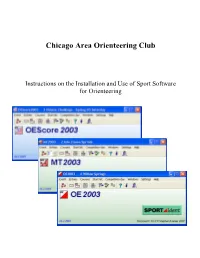

Chicago Area Orienteering Club Instructions on the Installation and Use of Sport Software for Orienteering Introduction This guide is for the use of members of the Chicago Area Orienteering Club (CAOC) and is not intended to replace or supersede any instructions from the owners of SPORTident, Sport Software or Brother. Should this guide be used by non-CAOC members they should be aware that much of the content has been derived from the methodology of “trial and error.” The CAOC E-Punch system is made up of components from several different vendors of software and hardware. The names to become familiar with are: • SPORTident – is the manufacturer of the physical equipment used by many orienteering clubs in North America and their web address is www.sportident.com. • Sport Software – is the leading manufacturer of software programs that manage the data being collected by SPORTident. Their web site at www.sportsoftware.de/eng/home.html is the source for almost all software used to run the e-punch system. Learning to use the Sport Software applications is the key to running the e-punch system and is the focus of this guide. Other related vendors are: • Brother – CAOC bought a Brother label printer to put the finishing touches to events by producing results on an adhesive label that can be attached to an individuals race map. The label layout is controlled through a Sport Software application and can be one of the harder parts of the system to learn. Many other report types are available for printing on regular paper but switching between printers during an event is not recommended. -

Land Navigation, Compass Skills & Orienteering = Pathfinding

LAND NAVIGATION, COMPASS SKILLS & ORIENTEERING = PATHFINDING TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. LAND NAVIGATION, COMPASS SKILLS & ORIENTEERING-------------------p2 1.1 FIRST AID 1.2 MAKE A PLAN 1.3 WHERE ARE YOU NOW & WHERE DO YOU WANT TO GO? 1.4 WHAT IS ORIENTEERING? What is LAND NAVIGATION? WHAT IS PATHFINDING? 1.5 LOOK AROUND YOU WHAT DO YOU SEE? 1.6 THE TOOLS IN THE TOOLBOX MAP & COMPASS PLUS A FEW NICE THINGS 2 HOW TO USE A COMPASS-------------------------------------------p4 2.1 2.2 PARTS OF A COMPASS 2.3 COMPASS DIRECTIONS 2.4 HOW TO USE A COMPASS 2.5 TAKING A BEARING & FOLLOWING IT 3 TOPOGRAPHIC MAP THE BASICS OF MAP READING---------------------p8 3.1 TERRAIN FEATURES- 3.2 CONTOUR LINES & ELEVATION 3.3 TOPO MAP SYMBOLS & COLORS 3.4 SCALE & DISTANCE MEASURING ON A MAP 3.5 HOW TO ORIENT A MAP 3.6 DECLINATION 3.7 SUMMARY OF COMPASS USES & TIPS FOR USING A COMPASS 4 DIFFERENT TYPES OF MAPS----------------------------------------p13 4.1 PLANIMETRIC 4.2 PICTORIAL 4.3 TOPOGRAPHIC(USGS, FOREST SERVICE & NATIONAL PARK) 4.4 ORIENTIEERING MAP 4.5 WHERE TO GET MAPS ON THE INTERNET 4.6 HOW TO MAKE YOUR OWN ORIENTEERING MAP 5 LAND NAVIGATION & ORIENTEERING--------------------------------p14 5.1 WHAT IS ORIENTEERING? 5.2 Orienteering as a sport 5.3 ORIENTEERING SYMBOLS 5.4 ORIENTERING VOCABULARY 6 ORIENTEERING-------------------------------------------------p17 6.1 CHOOSING YOUR COURSE COURSE LEVELS 6.2 DOING YOUR COURSE 6.3 CONTROL DESCRIPTION CARDS 6.4 CONTROL DESCRIPTIONS 6.5 GPS A TOOL OR A CRUTCH? 7 THINGS TO REMEMBER-------------------------------------------p22 -

George Mitchell Nature Preserve Orienteering Course— Instructions

George Mitchell Nature Preserve Orienteering Course— Instructions Welcome to the Mitchell Preserve Orienteering Course! This course consists of 15 wooden posts, emplaced and verified Fall 2018 by cadets with The Woodlands High School Air Force Junior ROTC Orienteering Team. Post locations and condition were verified Fall 2020. Posts are approximately three feet tall and are white, with the international orienteering-marker pattern painted on the top four inches of each side (see photo). On top of each post is a brown metal placard with white lettering. Each post has a unique three-letter identification code. Course participants should not know the coordinates of the posts, or the codes on each post, before using the course. Returning to the starting point with the codes verifies the participant did in fact find the post(s) in question without the aid of GPS. The orienteering map for this course was produced by the Houston Orienteering Club (http://hoc.us.orienteering.org). The trailhead is marked on the map as a solid purple triangle (the “starting point” symbol); posts (orienteering “control points”) are designated by open purple circles. Black vertical lines spaced 300m apart on the map indicate the direction of Magnetic North and are intended to be used with a compass to properly orient the map during use. Some posts are visible from one of the established trails; others may require more skilled use of compass bearing and pace count. Seasonal variations in plants may also obscure some posts from easy view (they are generally easier to see in the winter months). Control points on the map are numbered but are not connected by suggested routes; this is intentional so that groups using the course can develop their own routes with which to compete using all or some of the points as a “Sprint-O” (everyone runs the same route, competing for the fastest time) or to run an event as a “Score-O” (everyone competes within the same window of time, with points awarded based on how many points they can visit within that time). -

BULLETIN 1 BULLETIN 1 World MTBO Championships Junior World MTBO Championships

BULLETIN 1 BULLETIN 1 World MTBO Championships Junior World MTBO Championships 2020 Jeseník Czech Republic Organizers Event director Preliminary information David Aleš http://wmtboc2020.cz/ IOF [email protected] www.orienteering.com Event secretary ČSOS – Czech Orienteering Federation David Rajnoha Zátopkova 100/2, Senior Event Adviser [email protected] 169 00 Praha 6 Ludomir Parfianowicz +420 775 696 373 [email protected] +420 737 011 553 National controller www.csos.cz Milan Meier EVENT CENTER The city of Jeseník Dear supporters of the Mountain Bike Orienteering, the Czech Orienteering Federation is pleased to welcome you in the scenic surroundings of the spa town Jeseník, enclosed by the mountains, in the heart of the range Hrubý Jeseník, in the countryside full of astonishing nature, beautiful greenery and silence, in the area of healing springs and clean air. The city of Jeseník, 250 km distant from the capital of the Czech Republic – Prague, is with 12 500 inhab- itants the administrative and cultural center of the region. During the WMTBOC the city will also become the administrative and organizational center of the competi- tions, the place of the ceremonies and the place of competitors accommodation. We are delighted to introduce you to the new, attractive, beautiful and demanding terrains of the Jeseníky and the Žulovská Pahorkatina that have never been used for a top-level MTBO event. We are awaiting You in the Czech Republic at the WMTBOC 2020. GENERAL MAP PROGRAM Saturday 15th Aug Arrival & Training Sunday 16th Aug Model event Monday 17th Aug Sprint, Opening ceremony Tuesday 18th Aug Mass start Wednesday 19th Aug Middle distance Thursday 20th Aug Rest day Friday 21th Aug Long distance Saturday 22th Aug Relay, Closing Ceremony Sunday 23th Aug Departure CLASSES For the Long distance competition, the number of competitors who may enter is limited. -

Maps for Different Forms of Orienteering

MAPS FOR DIFFERENT FORMS OF ORIENTEERING László Zentai Eötvös Loránd University, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/A H-1117 Budapest, Hungary [email protected] Abstract: Orienteering became a worldwide sport in the last 25-30 years. Orienteering maps are one of the very few types of maps that have the same specifications all over the world. Orienteering maps are special, because to make them suitable for orienteering the map makers have to be familiar not only with the map specifications, but also with the rules and traditions of the sport. The early period of orienteering maps was the age of homemade maps. Maps were made by orienteers using available tourist or topographic maps and only after the availability of cheaper reproduction techniques started the process of special field- working. The International Orienteering Federation (IOF) was formed in 1961. The Map Commission (MC) of the IOF has introduced different specifications for the official disciplines (before 2000 the ski-orienteering and foot-orienteering were the only official disciplines). The last version of the specification, the International Standard for Orienteering Maps (ISOM) was published in 2000 and included specifications for foot- orienteering, ski-orienteering, mountain-bike orienteering. A new format, the sprint competition, required new map specifications (ISSOM) which were finalized and published in 2007. The aim of orienteering map specifications is to provide rules that can accommodate many different types of terrain around the world and various forms of orienteering. We can use the experience of the official disciplines for developing new specifications: the official disciplines and formats were developed in the past 30 years (most of them are even newer). -

PRESIDENT's LETTER Covering the White Winter World WELCOME

July 11, 2019 PRESIDENT’S LETTER Covering The White Winter World When the Eastern Slope Inn in North Conway, N.H., hosted the first organizational meeting of the Eastern Ski Writers Association in September 1962, the focus was clearly on covering skiing, then best defined as alpine downhill. Today if you write, blog, broadcast, photograph, video, Tweet or Insta to cover a winter sport or leisure pastime that occurs on snow, you’ll find a home at NASJA. Yes, we’re talking about you competitive or non-competitive alpine skiing, Nordic skiing, dog sledding, ski jumping, ski orienteering, snowboarding, snowshoeing, uphilling, fat biking, even snow dancing. Snowmobiling not so much, but we’ve expanded the definition of snowsports in the past, and can do so again as popular leisure activities change with the times. We service the needs of our readers, viewers and online users with news and information they can use to decide how to spend those precious few hours in the white winter world when they’re not sleeping, eating, working, doing housework, in school, or dare we say, zoned out in front of a screen. NASJA members take pride in helping the North American consumer get the most out of their free time, a most treasured commodity. So if you’re a journalist who covers snowsports, help us make NASJA your organization, one that services your needs best. - Jeff Blumenfeld NASJA President WELCOME PETE PA NDOLI, NEW NA SJA TREA SURER The NASJA board is pleased to announce the selection of new treasurer Pete Pandoli, from Moseley, Virginia. -

BARK Newsletter

Bend Adventure Racing Klub News April, 2004 The Sharing adventure in the outdoors BBAARRKK a.k.a www.BARKracing.com “Getting Lost Together” Old BARK Bests Young BARK at Rogaine —What‘s a Rogaine?“ is the first question I‘m asked indistinct but rough sagebrush and lava rock of the when describing last weekend‘s race. —Is it a race desert seemed plenty. to grow hair?“ No, and it‘s not sponsored by a large pharmaceutical company. A rogaine is a type of Final Score: Young BARK- 1630; Old BARK- 1720. orienteering event and, on April 4th, several Bring on the Black Butte Porter! BARKers competed in the High Desert Drifter 6- Hour Mini-Rogaine organized by the Oregon By the way, "rogaine" is an Cascades Orienteering Klub. acronym that was invented in the 1970s from Rugged Outdoor Rogaining is the sport of long distance cross- Group Activity Involving country navigation in which teams visit as many Navigation and Endurance, or checkpoints (called control points in orienteering from a combination of the lingo) as possible in a given time period. This type inventor's names (ROd, GAIl, and of event is also called Score-O because each control NEil), depending on who you ask. is given a point value, sometimes different amounts Or you can go do a Billy Goat. based of difficulty, and the team with the most points wins. Teams can visit controls in any order - Pam Stevenson and must plan their course to get the maximum number of points. They navigate by map and compass between points that are marked with Volunteer for the distinctive orange and white control markers. -

Veterans Oasis Park Orienteering Course

Mayor and the Chandler City Council Veterans Oasis ORIENTEERING COURSE After completing the RED course scratch here ORIENTEERING In orienteering you use compass bearings to check your post #’s. and distances to locate a series of checkpoints. You follow the route that will Answer Key: 1, 2, 4, 3, 9, 8, 7, 5, 6, 0, 6, 1 COURSE help you find all the checkpoints and get to the finish line. On the easy (orange) course each checkpoint is marked to help you find the way. The difficult red course is not Eagle Project by marked on the map and the posts are not in Thomas Driggs | Troop 285 numerical order. Follow the sequence and Ryley Coder | Troop 280 write in the post #’s as you go. Check the answer key after completing the course The courses can be used for recreation, orienteering practice, or BSA Orienteering/ Rank Advancement. STEPS TO ORIENTEERING To successfully orienteer you will need to complete the following steps. Environmental Education Center 1. Obtain a map and a compass. 4050 East Chandler Heights Road 2. Determine your pace. Chandler, AZ 85249 (NE corner of Chandler Heights and Lindsay roads) 3. Orient the map to the land. 4. Determine where you are on the map and where you want to go. 5. Determine the direction (compass direction) between the two points and the distance. 6. Using the compass, walk in the direction found in step five, counting your paces chandleraz.gov/eec to determine the distance. ABOUT THE PARK Veterans Oasis Park covers 113 acres and features RED COURSE | DIFFICULT 1 both lush wetland and arid habitat suitable for Control Heading Distance Record the diverse plants and wildlife of the Sonoran Sequence (Magnetic) (feet) Post # Desert.